Will the real European Left stand up?

Murray Smith responds to the European dimension of the ‘flutter’ articles. He is a member of the anti-capitalist party déi Lenk in Luxembourg, and of the Executive Board of the Party of the European Left.

Murray Smith responds to the European dimension of the ‘flutter’ articles. He is a member of the anti-capitalist party déi Lenk in Luxembourg, and of the Executive Board of the Party of the European Left.

Having followed with sympathy the emergence of Left Unity and the possibility of a new party of the Left being launched, I read with interest the two-part article by an anonymous figure, who may or may not be called Michael Ford, which may or may not be a pseudonym. I’m sure we’ll find out. For the purposes of this article, I will refer to him as Ford. In any case, whoever wrote it, the aim of the article is clearly to try and discredit the perspective of building a new party to the left of Labour and validate that of working with/within the Labour Party to drive it to the left. There will undoubtedly be many replies to Ford from people who are directly involved in politics in Britain, which I am not at present. However, an important part of Ford’s argument is to try and demonstrate that the political forces to the left of social democracy in Europe don’t amount to much, either politically or in terms of their support. In doing so, frankly, he paints a picture which has little relation to reality. This is what I want to take up [1].

At the end of the first part of his article Ford writes: “The traditions of the British labour movement are in many respects worse than those in the countries listed. That can be debated, but they are unarguably enormously different.” That is certainly true. The British labour movement has features which are unique in Europe. In particular, this is true of the Labour Party, in the sense of trade union affiliation and the role of the unions in the party. But is the difference absolute or only relative? If you compare Britain with France it looks pretty absolute. If the comparison is made with Northern Europe (Scandinavia, Germany, the Netherlands…), it is much less so. In those countries you have mass social-democratic parties which have historically had the loyalty of most of the working class and mass, unitary trade unions which have supported these parties. Quite a different picture to that of Southern Europe with mass communist parties and divided trade unions and where the (electoral) dominance of social democracy dates only from the 1970s. Nevertheless there are significant parties which are not only to the left of social democracy but are clearly anti-capitalist in both Northern and Southern Europe. They are stronger in the South than in the North, but that is to be expected.

Let us look at what is common to the whole of Europe. The first thing is that social democracy is now, and has been for some time, part of the neo-liberal consensus. Not without internal tensions, in some cases. The second thing is that as a result, globally and with ups and downs, but overall, it is losing support from its traditional supporters and a space is opening up to the left. Now a space is not the same as a vacuum, which as we know Nature abhors, and which will be filled automatically by something or other. The space to the left of social democracy consists of people, real living people who have had enough of parties which betray their hopes, which no longer defend them but attack them. As a result they may be open to a party or parties which offer another perspective, one that breaks with the neo-liberal consensus. Whether this possibility becomes reality, and to what extent, depends on politics – on political action, on the ability of anti-capitalist forces to come together and to offer political perspectives.

Of course the space to the left of social democracy has never been empty, nor is it now. There are the Communist parties or their successor parties; there are the various far-left groups, mostly Trotskyist; there are the Greens, which in some countries at least are to the left of social democracy.

First of all, let us look at the Communist parties, because the way in which Ford approaches them is the most at variance with reality. He writes: “Communist parties have disappeared or been reduced to the margins (with a few exceptions) and, in the case of many of the former ruling parties, openly converted to social-democracy and, hence, variants of neo-liberalism”.

The second part of his statement is certainly true as regards most (but not all) of the former ruling parties in Eastern Europe. The first part is a strange thing to write in 2013, though Ford is not alone in holding this opinion. Ten, twelve or fifteen years ago I thought that the West European Communist Parties would either disappear, become social-democratized (or become satellites of social democracy) or subsist as diminishing and marginal “orthodox” sects. That is not the course events have taken. The only West European party to have simply gone over to social democracy (and indeed beyond it) was the Italian Communist Party, at the price of an important split. The only party to have simply dissolved is the British one. There is a series of parties which consider themselves orthodox but which in most countries are quite weak and marginal, with the notable exceptions of the Greek (KKE)and Portuguese (PCP)parties. Then there are those communist parties which are part of the Party of the European Left (EL).

This is the Euro-Left which is the main target of Ford’s criticism, so let us deal with that. In the first place, he writes at one point: “on the basis of this short summary [in which he covers Greece, France, Italy and Germany, M.S.] we can say that the euro-left is hardly decisive outside Greece, that it polls less than when it was explicitly Communist in times gone by…”. In times gone by…well, the times when it was enough to be explicitly Communist and to defend “Soviet socialism” have indeed gone by, and they’re not coming back. At another point, in relation to France, he writes: “the Left Front polls less than half of the vote secured a generation or so ago by the PCF”. You have to go back to 1978 to find the PCF polling more than 20 per cent in a national election. Since then, in that “generation or so” rather a lot has happened: the neo-liberal offensive, a change in the relationship of class forces within countries and on a global scale, the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the ideological offensive, “the end of history”…That does not only affect the European Left. The Portuguese Communist Party, which is explicitly Communist (as, by the way, are the French, Spanish, Austrian, etc.) and not part of the EL, was getting 15-20 per cent in the 1970s and 80s and less than 10 per cent from the early 90s until 2011. Of course, not everything can be explained by the broad objective factors mentioned above. Political choices can make things better or worse. The PCF paid a certain price for its participation in the Jospin government from1997-2002 and also from an ill-conceived presidential campaign in 2007. Conversely, it has benefited from its role in the 2005 referendum campaign, from its increasingly clear differentiation from the Socialist Party and from the strategy of the Left Front.

Now let us take up “hardly decisive outside Greece”. In fact, Greece is the most advanced point of a tendency towards the strengthening of parties to the left of social democracy which is also evident in other countries. In Denmark the Red-Green Alliance was formed in 1989 (not the best year to launch an anti-capitalist party, one might think) by the Danish Communist Party, the Danish section of the Fourth International, Left Socialists and Maoists. It has been in Parliament since 1994 and has patiently established itself as apolitical force over the years. It is now stronger than it has ever been ever been with over 10,000 members . At the last election in 2011 it won 6.7 per cent of the vote and 12 MPs. In the latest opinion poll it has 14.9 per cent, as against 16.1 per cent for the social-democrats who head the centre-left government. In Portugal the Left Bloc was formed in 1999 by forces from Trotskyist and Maoist backgrounds along with a current from the PCP. From there it grew rapidly and progressed at each election until 2011, when it suffered a serious setback in elections conducted under the shadow of the Troika, falling to just over 5 per cent. In the latest opinion poll the Bloc has 8.8 per cent and the PCP 12.1 per cent, a total of 21 per cent. Fortunately the PCP is not as sectarian as the KKE and there is some collaboration between it and the Left Bloc.

In Spain the Communist Party is the core of the United Left, which was established in 1986 in the continuity of the campaign against Spain joining NATO. Its record has been somewhat chequered over the years. However in the last period IU has progressed in the national elections in 2011 and in regional elections and currently stands at around 16 per cent in the opinion polls. This is not an automatic result of the crisis; it is the result of a clear positioning to the left of social democracy on the one hand, presence in all the movements of resistance to austerity and other a willingness to work with the new social movements, not always without problems.

Concerning France, it might have seemed, in the 1990s, under the stewardship of Robert Hue and with the PCF’s participation in the Jospin government from 1997-2002, that the PCF was destined to become a satellite of the Socialist Party (PS) and/or to disintegrate. However that is not what happened – although Hue and a few followers subsequently left the PCF and now constitute a small group which is precisely a satellite of the PS. Through a process of political clarification that was not always easy, under Marie-George Buffet as national secretary from 2001-2010, succeeded by Pierre Laurent, the party began to be rebuilt, with a clear differentiation from the Socialist Party and readiness to work with other forces on the left. This was first clearly seen in the campaign against the proposed European constitution in 2005. It was crystallized with the formation of the Left Front in 2009. With this orientation the PCF halted its decline and began to recruit from 2005 onwards. In the 2012 elections not only did Left Front candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon get 11 per cent in the presidential election (the best vote for a candidate to the left of the PS since 1981), but the results of the legislative elections, where most of the candidates were PCF, were in 90 per cent of constituencies superior to 2007. The Left Front has progressed in each election where it has stood (European 2009, regional 2010, local 2011, presidential and legislative 2012). It now involves nine organizations, including not only the PCF and the Left Party, formed by Mélenchon when he left the PS in 2008, but three organizations from an LCR-NPA background.

And of course it is not just about elections; on May 5 a demonstration called by the Left Front mobilized well over a hundred thousand people – a massive expression of protest against the austerity policies of Hollande.

A final word on the PCF: I attended its 36th congress in February as an observer. To put it very succinctly, what I did not see was a party that was in crisis, aging, shrunken, without a strategy and thinking of nothing else but how to get into government. In other words, not what has been the staple fare of commentaries in the bourgeois press and by some on the left for quite a few years now. What I did see was a party full of confidence, with many young people, whose discussions centred on how to organize the fightback against Hollande’ s policies and build a political alternative. Of the delegates, 20 per cent were under 30 and 30 per cent had joined in the last five years. And of course three-quarters of them were wage-earners.

The examples above show the reality and the potential of forces to the left of social democracy in Europe. But there also some problems. Since its breakthroughs in the 2005 and 2009 federal elections and in regional elections in the West, Die Linke has experienced difficulties and setbacks. In the first place there are objective reasons. At the present time a large part of the German working class is enjoying prosperity and is not so open to the discourse of the Left. There are also problems of integrating the components of Die Linke in the East and the West. In the East the PDS was one of only two former ruling parties in the Soviet bloc not to embrace the process of capitalist restoration (the other was what is now the CPBM in the Czech Republic). As a result it has a solid base of support over 20 per cent in several Lander and a network of local councilors. In the West the forces coming from the SPD and the radical Left had to start pretty much from scratch, with the exception of Oskar Lafontaine’s base in the Saar. As things stand now, however, the situation is difficult but certainly not catastrophic and unless there is a very big upset Die Linke will keep its parliamentary group. In Italy the situation is much worse. The participation of the PRC in the Prodi government from 2006-08 cost it much of its electoral support, including, but not only, because of its backing for sending Italian troops to Afghanistan. In 2008 it lost all its parliamentary representation, split almost 50-50 and has since then been in difficulties, waging an unsuccessful campaign in what was admittedly a very difficult election in February. It must also be said that none of the three left groups which split from Rifondazione in 2006-08 has since made any impact. It will not be easy to rebuild the Left in Italy, but Rifondazione remains the starting-point.

The case of Greece and Syriza merits a few remarks. Since Syriza made its electoral breakthrough in 2012, everyone on the left in Europe has had to sit up and take notice. But Syriza did not fall from the sky. Its central component, Synaspismos, is a product of a complex process of splits and realignments in the Greek communist movement that began in 1968. And the Syriza coalition (now in the process of becoming a party), which was created in 2004, and drew in currents from Eurocommunism, Trotskyism and Maoism, was the result of a political choice by Syriza; Nor was the success of Syriza a mechanical effect of the crisis. It was the result of a political orientation that combined an absolute refusal of austerity and the diktats of the Troika and the proposal to other forces on the left to form a government of the Left – a proposal refused by both the Democratic Left and the KKE.

How does Ford characterize the European Left politically? “The euro-Left parties stand to the left of contemporary social democracy in advocating more radical measures, in varying degrees, to tackle the economic crisis. They are, on the other hand, constitutional and electoral parties – they do not aim at revolution. Their measure is electoral support which they seek to secure through advocating pro-welfare and egalitarian policies which broadly mitigate the effects of the slump on the working-class. Their ultimate aim may be a socialist society (although this is not always clear), but it is to be attained primarily by parliamentary means. Broadly they disown the record of socialism and revolutionary politics in the twentieth century”. And elsewhere “they are explicitly reformist”. And, pride of place for this one, “the summit of the ambitions of the Left parties Europe-wide at present is to secure enough parliamentary seats to be considered a coalition partner in a government which would be dominated by the “old” social democratic parties”. Firstly, of all, broadly, in my experience, these parties do not disown the record of socialism and revolutionary politics in the twentieth century. They may interpret it more or less critically, and not all in the same way, and often not exactly as I would, but they certainly do not disown it. Perhaps Ford means that they do not agree with his version of that record, which on the basis of various references in his document, seems to be rather neo-Stalinist. Secondly, concerning the “summit of their ambitions”. Perhaps Ford would like to explain why Syriza refused to consider a governmental alliance with any pro-memorandum party, including PASOK; why the RGA only gives critical support to the Danish centre-left government from the outside but did not join it; why, above all, the PCF voted last year, on its National Council, in a special conference and by an internal referendum, not to take part in the present SP-led government (the referendum of the membership produced a vote of nearly 95 per cent against participation). Of course, in the recent past the PCF (in 1997-2002) and the PRC in Italy have participated in such governments. Those were not in my opinion positive experiences. More importantly, it seems clear that they are now considered by most members of the parties concerned as not to be repeated, though it would be foolish to rule out any governmental alliance with social-democrats under any circumstances. It would, however, be more true today to say that the ambition of the parties of the EL is to change the balance of forces on the left, to replace social democracy as the dominant force. Thirdly, the objective of going beyond capitalism and of a socialist society is not in doubt. Let us see what the French Communist Party says about it:

“To those who speak of moralizing capitalism in order better to keep it, we say that the enterprise is vain and that the manoeuvre will not work. Money has no conscience. Capitalism is incapable of offering any other perspective than the enslavement of the vast majority of human beings. To those who call on us to be reasonable and who propose to regulate capitalism, we say that it is an illusory goal. Without the will to take power from the financial markets and the big capitalists, experience has shown that there is no significant result. There is a contradiction that is increasingly unbearable between capitalism and social progress, between capitalism and democracy, between capitalism and cultural development, between capitalism and ecology, between capitalism and peace. That is why we talk about revolution. A social, citizens’, peaceful, democratic revolution, and not the taking of power by a minority. A process of credible and ambitious change, aiming to break with the logic of the system. That is why we speak of communism, a communism for a new generation”. (Extract from the political resolution of the 36th congress of the PCF, February 2013, my translation).

(I have quoted this because it is particularly clear, coming from one of the main parties of the European Left. But the aim of replacing capitalism rather than reforming it is shared by other parties, formulated more or less clearly).

Now you can, if you wish, say that the PCF is reformist. But on the basis of the above, you can hardly accuse it of being simply in favour of a modified form of capitalism. And as for reformism…Perhaps Ford has a very clear idea about the demarcation between reform and revolution in Europe today. Quite a few other people think they have. I think things are rather more complicated than that. There is the small detail that there has never been a socialist revolution in an advanced capitalist country with a more or less long tradition of bourgeois democracy. Never, nowhere. The strategy and tactics for making one will have to be developed in the course of the struggle and they will be very different from Russia in 1917, not to mention China, Vietnam, Cuba, Yugoslavia. They will certainly involve a combination of mass mobilizations and battles on the electoral terrain and in parliamentary institutions. That will involve in particular winning a majority in elections based on universal suffrage, and not only once. In fact it is difficult to see a revolutionary process that does not involve a left alliance winning an election. All of that will be the subject of debates based on experience, and no one has a blueprint. Rather than establishing an a priori cleavage between reformists and revolutionaries it is better to look at what anti-capitalist measures a left government should take and how, how to mobilize support for them, how to counter economic sabotage and political pressures from the Right, etc. Not to mention what kind of a post-capitalist society we envisage.

Of course there are other forces on the left in Europe apart from the EL. But it is there that there is a dynamic and an opposition to neo-liberal capitalism that presents an alternative on a European level and seeks to build a European social and political front.

Apart from the “orthodox” Communist parties I have mentioned, there are far-left organizations which remain outside broad fronts and coalitions like Syriza, the United Left and the Left Front. They tend to be somewhat marginalized as a result but continue to play a role. The NPA, after a promising start, paid a heavy price for not having understood the dynamic of the Left Front. But it still has some forces and is not, under its present leadership, opposed to common actions with the Left Front, as on the May 5 demonstration.

To conclude, just a few words on Britain. The failure of attempts to create a new force to the left of Labour are well-known. But the potential is there, as was clearly shown by the success of the SSP before the train wreck of the Sheridan affair. Not only electoral success, but trade union support and even affiliation. And there are reasons for past failures. Arthur Scargill will go down in history as a courageous and principled working-class leader. But the failure of the SLP, which had real potential, was essentially due to his sectarian and Stalinist conception of how to organize the party. As for the Socialist Alliance-Respect sequence, both the SWP and the Socialist Party played extremely negative roles, as they also did, in alliance for once, in the crisis of the SSP. As for TUSC, it’s not a party, it’s not meant to be one, it’s meant to not be one, and it fulfils that role perfectly.

Ford says that “if the new Left Party succeeds, it will certainly represent a sociological first”. Maybe it will. It wouldn’t be the first win against the odds. Who would have bet on the success of a disparate collection of leftists in Denmark or Portugal? Or that Syriza would go from 4 per cent to 27 per cent in a few months? And you have to start with what you have. No new Arthur Scargill is on the horizon. Nor is any split from Labour. Leaving aside the Greens, there are three left organizations with memberships in four figures, say between 1,000 and 2,000 – the CPB, the SWP and the SP. None of them is likely to play a positive role in building a new party, to put it mildly. So if you have a few thousand signatures and eighty or a hundred local groups, that’s what you start with. Or you could give up and join the Labour Party. But I’ll leave the argument against that to others.

[1] For an overview of the new parties of the Left in Europe and a detailed look at several of them, see Kate Hudson, The New European Left, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

14 comments

14 responses to “Will the real European Left stand up?”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

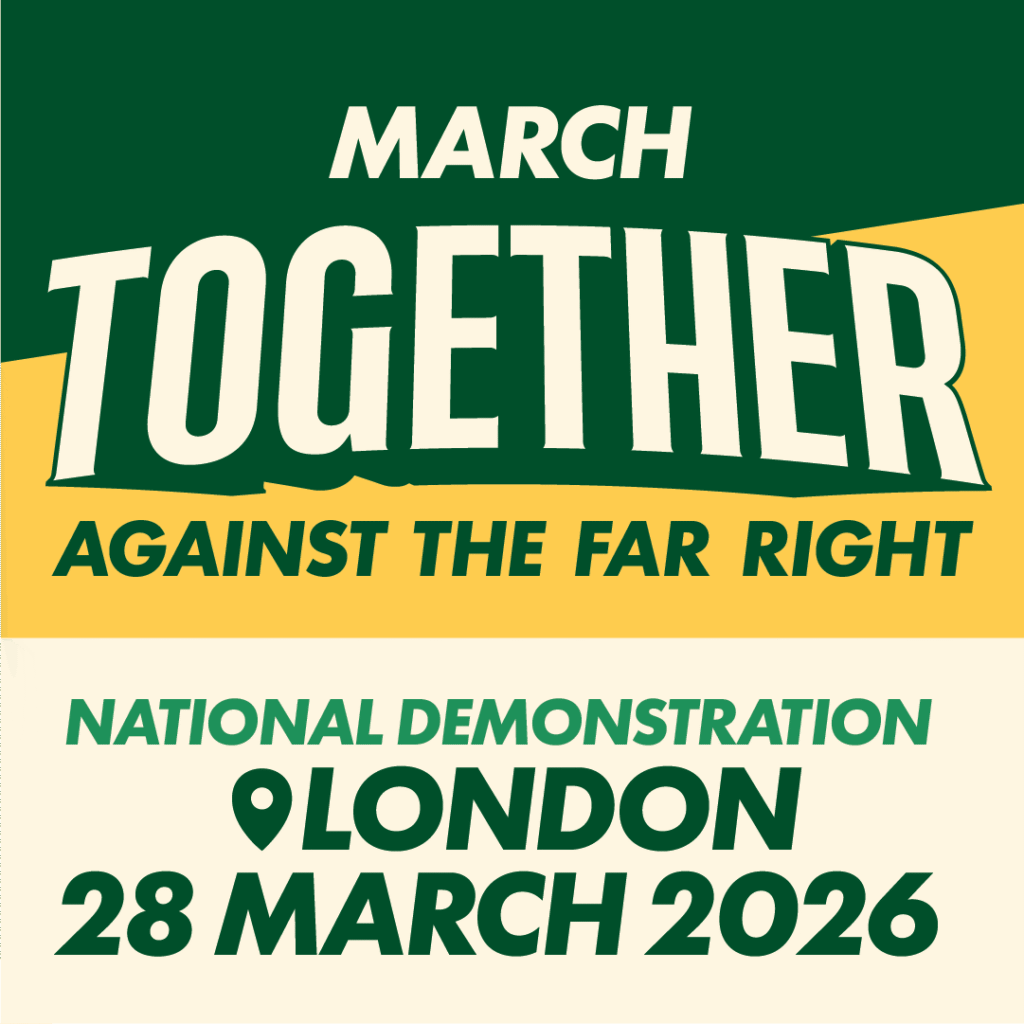

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Is it possible for you to email me a copy of this article as a PDF or WORD document as I would like to print if off (the web version seems to be very confusing with different typefaces etc., for some reason) and circulate to a few other people Thanks.

Absolutely. I agree with the analysis of most of this article. I don’t accept that those who reject the obsession with 1917, and the party-building methods it has made infamous, are all necessarily ‘reformist’.

There is a huge gap between these two poles and that is what Left Unity should be about – building an anti-capitalist party which stands for replacing capitalism with a democratic alternative system – though we can argue about the details of such a ‘socialist’ system.

I realise that this next bit is getting ahead of ourselves a bit ;) but the strategic/tactical balance between electoral work versus revolutionary/mass action will be an organic and (dare I say!) a dialectical one. Building a huge movement of popular/working class activism can lead to electoral success, leading to greater activism and an explicit link between elections and mass action (or revolution) to ensure that the ruling class do not use economic or state power to crush the left government. The mass action is needed further to guarantee control of state power by the popular movement and ITS government.

Phew! I need a lie down now, but it’d good to dream sometimes.

This was a very interesting and plausible contribution, Murray, until you had to go and spoil it: “Arthur Scargill will go down in history as a courageous and principled working-class leader.” It leads me to question the other facts/opinions in your piece – a pity as they ring true and are a good rebuttal to Mondeo-man.

I will never forget when the organisation I worked in invited him to speak, not long after the strike. The result was a generational split that I have never seen anything like since. Younger people who had little in common politically were all unanimous in their opinion of Scargill as sad and irrelevant. The older people looked upon him with a reverence.

But the point is this: the ‘great strike’ should have been a learning experience for the left about how not to run a struggle. Of course some great stuff happened – I was involved more or less full-time throughout – but very little of it down to old Arthur. There was plenty of bad: like the playing into the divide-and-rule that undermined the strike from the start; the stupid tactics, going for macho stand-offs (Orgreave) rather than listening to his own members good advice; the intransigence and castigation of anyone who did not agree with him – which continued well after the strike, ending in the sad legal battle with his own union over the aristocracy of labour pad.

Most of all it is the politics of “I’m always right and will be forever, have no regrets, anyone who differs is wrong and it is only due to betrayals that the strike was lost” etc. Sound familiar? That is not exclusively ‘Stalinist’ but a macho megalomania that has a malign effect on everything it molests. No surprise then that the SLP bombed and that other sects run on similar principles are imploding as we speak or never grow and have a horrible history of pimping off other people’s hard work. Let’s hope that those politics have no trace in LU.

Really useful article here Murray. I couldn’t believe how badly informed the secret senior labour movement person was about what was or is happening on the left in Europe. Just one point. You state: “It will not be easy to rebuild the Left in Italy, but Rifondazione remains the starting-point.” I think this is only very partly true in the sense that people have to take that relatively recent experience into account when discussing how to rebuild now. Also physically many of the activists involved in that project will be also be an important component of any reconstruction today. What is left of Rifondazione as a name today is the group led by Paulo Ferrero who was a driving force behind the constitution of the Ingroia led coalition in the recent electons. His intervention along with other apparatuses and top leaders like Di Liberto and Di Pietro led to this coalition being set up in a way completely differently to how the original movers of the Cambiare Se Puo appeal wanted. It became a top down rather than democratically organised bottom up coalition representing the real movements. The main considerations of Ferrero and Di Pietro was to regain their parliamentary representatives. They received a derisory vote. Today the redundant workers of the Rifondazione apparatus are in open war with the leadership over compensation. The other major component of Rifondazione, who just failed to get a majority and continue with the name, is Vendola’s SEL which hooked its wagon to the PD electoral slate. It was rewarded with a decent number of MPs or this ambiguous soft left line but with its erstwhile ally now in bed again with Berlusconi and Monti in the new government Vendola and friends are in opposition…but an opposition that will be constructive he says. He even congratulated Letta, the moderate PM! So I am not sure that Rifondazione will be the major starting point for reconstruction. Today, the 11th of May there is a Left Unity type meeting going on in Bologna which is trying to start the rebuilding. Turigliatto, Russo Spena, Cremaschi and other ‘historic’ leaders of the radical left are involved. Other forces on the radical left are even more pessimistic about the situation and believe such traditional left initiatives are not what is needed and that the real question is building networks and movements, building everything from the bottom up and creating new spaces of resistance. Of course the two processes could go on together. The ferment inside the PD with the youth particularly in revolt over the new national coalition provides some additional purchase for any left unity type projects.

I hope Left Unity succeeds – indeed that the infant global movement towards genuine morality in politics races into properly underpinned power. But I must say I am amazed (with regard to the article – and particularly to Dave K’s significantly out-of-date comments – above) that Beppe Grillo’s 5 Star Movement’s incredible and well-deserved success in winning more seats than any other single party in the recent Italian election – and then being effectively outlawed by the traditionally criminal + weak forces of the exhausted & historically divided right & left (pace Vendola perhaps?) – hasn’t even been discussed. It is a real Movement towards morality – and Left Unity will, I most sincerely hope, be making seriouis contact with it.

Yes the M5S movement is significant and is the main intransigeant opposition in parliament and to a degree outside. People on left need to work with its militants on campaigns and actions. However you also have to read Grillo’s blog concerning May 1st where he tends to write off the organised trade union movement completely. One thing is to criticise how the CGIL, UIL and CISL leaderships are collaborating with the austerity government it is another thing to ridiculise and sneer at organisations that can on the ground defend working people. He has defined unions as just representing a bloated, corrupt public sector or the political caste. I have written elsewhere on this site and on the socialist resistance site on M5S and the left. It is definitely not a UKIP or right wing force but it is not a clearly left wing force either. You might like to examine some of Grillo’s comments this week again on the right of migrants born in Italy to become Italian citizens by right. He is fudging it again by calling for a referendum to decide on this.

It doesn’t invalidate the article but there were not well over 100 000 at the 5th of May demonstration in Paris. 100 000 would already be a generous estimate according to all the different left forces that have discussed it. (We ignore of course the 30 000 figure of the police.)

As the author says, he’s not working in UK politics, so his views are a little abstract.

Of all the “left” parties in Europe, Syriza has come closest to winning power.

This was on the back of massive disillusion with PASOK and its role in accepting Austerity in Greece from 2009-12.

Pasok’s vote consequently collapsed from 43.92% in 2009, to 13.18% in 2012.

We’ve seen no such a collapse in the Labour Party’s vote in Britain.

The fact that Syriza didn’t win was partly down to sectarianism towards it by other parties of the left.

Criticisms of its programme must be made within the context of supporting its implementation.

A Syriza-led government would meet serious resistance from the leaders of the EU and International Capital.

Its leadership will either compromise, or fight.

To ensure that it’s the latter, socialists need to be organized within the Syriza coalition.

The situation in Britain is very different at this stage.

The biggest danger we face can be seen by simply adding up the Tory and UKIP votes.

Together, these two right wing parties had 48% of the national vote in the May Council elections.

This gives UKIP leverage over Tory Party policy and the possibility of forcing policy changes, or even a coalition on the Tory leadership.

In urban area nearest to me, the total votes cast in the May 2013 election were:-

Labour 10,000

Conservatives 6,300

UKIP 4,200

LibDem 2,400

Greens 1,800

(This is based on a 30% turnout – half of what could be expected at a General Election.)

Labour has controls of the City Council and has been able to enact some modest reforms; building council houses for the first time in 20 years and has implementing a living wage.

This suggests that best tactic for the next General Election is not a head on national challenge to the Labour Party.

This is not even a practical propostion, not even with 8,000 members (far less than the ILP, or even the CPGB had at their peak)

There may be one or two areas where socialist candidates could win against right wing Labour.

But the main task is to be supportive of the return of a Labour government, while not being uncritical of the policies of the Miliband leadership.

Len McCluskey’s warning over his policies will become a much more urgent question when Labour are in power again.

The Peoples Assembly has shown that its possible to organise members of the unions, the LP, Greens and Socialists to campaign and discuss the policies we need.

Even on your optimistic prediction of 60% in a general election, that still leaves 40% of, at present, non-voters for LU to work with for the next 7 years and plan for a massive challenge in 2020 (NOT 2015: too soon) – after we prove ourselves to be the same people, with a track record of struggle with our fellow citizens on a clear and simple platform of:

PEACE: no more starting wars – ever (troops home, counseled and retrained for socially useful jobs); UK nuclear and offensive weapons disarmament now – leave NATO and high profile international initiative to transform security council to non-offensive group; huge programme of civil service, armed forces and police re-education / restructure

EQUALITY: using Equality Trust, NEF et al evidence to argue the case for a much more equal society – redistribution of income and status – a cultural revolution focusing on gender and race initially; negotiation with unions to become more democratic and accountable to members in exchange for repealing anti-tu laws

SUSTAINABILITY: immediate full employment via programme of training, green energy, retrofit and new housing (to let, not for sale); transition from arms/nuclear/prisons to socially useful production/prevention/health & care services

COMMON OWNERSHIP: banks, insurance, transport, utilities, crown estates and property – plus massive expansion of mutuals and workers’ co-ops – alongside a transformation of management to enable worker / citizen control (with equality – above)

“Today, the 11th of May there is a Left Unity type meeting going on in Bologna which is trying to start the rebuilding. Turigliatto, Russo Spena, ‘Cremaschi and other ‘historic’ leaders of the radical left are involved. Other forces on the radical left are even more pessimistic about the situation and believe such traditional left initiatives are not what is needed and that the real question is building networks and movements, building everything from the bottom up and creating new spaces of resistance. Of course the two processes could go on together. The ferment inside the PD with the youth particularly in revolt over the new national coalition provides some additional purchase for any left unity type projects.”

Like to hear more about this, progressive politics in Italy is always interesting.

Murray largely fails to include Eastern Europe in Europe. Why? The situation across the ‘desert of transition’ under capitalism restored is a veritable epistemological arsenal for the international left.

The EL has links with various various member or observer parties there. Kate Hudson THE NEW EUROPEAN LEFT (2012), footnoted by Murray, has some comment on Marxist parties in Eastern Europe, such as the CPRF in Russia (http://goo.gl/2Ls6e ), which has a strong electoral base (ca. 20% in electoral terms). Hudson devotes an entire chapter (pp. 132-146) to the CP of Bohemia and Moravia in the Czech Republic, a growing party that Murray mentions only by name in passing.

He does not look at the RKRP, Russian Communist Workers Party

(www.rkrp-rpk.ru/ ), which has a small base and a strong youth movement as well. Here a recent RKRP video from still alive socialist holiday May 9:

http://rkrp-rpk.ru/content/view/9294/63/ many speakers

GERMANY: What about the DKP in Germany (http://www.dkp.de/ ), to the left of much of DIE LINKE? AKL (Anti-Capitalist Left) in Germany is a formation inside DIE LINKE on its more radical left, and somewhat independent of the party structures and positions http://www.antikapitalistische-linke.de/ .

I deliberately chose not to try and deal with Central and Eastern Europe, because the situation there is so different from Western Europe and it would have considerably lengthened the article. And also because our anonymous critic concentrated on parties in Western Europe. Not at all because what is happening in Eastern Europe is not interesting or important, on the contrary. The EL does indeed have member and observer parties there. Both the CPBM and the DKP are observer parties, and we pay a lot of attention to the entire region.

It would be futile for Left Unity not to affiliate with the GUE-NGL so as to establish real ties with SYRIZA, Die Linke, Front de gauche, etc.

On a sidenote, I hope Left Unity does *not* replicate the “this is true of the Labour Party, in the sense of trade union affiliation and the role of the unions in the party” part. If it is to establish connections with the broader strata of what are called “freeters” in Japan and “precariat” in economist circles (outside that recent British Sociology horse manure), LU must import Continentalism.

‘Leaving aside the Greens, there are three left organizations with memberships in four figures, say between 1,000 and 2,000 – the CPB, the SWP and the SP. None of them is likely to play a positive role in building a new party, to put it mildly.’

On a technical point, I would also add the Respect Party (and possibly still the SLP), which probably lies between thsoe two membership figures, though I doubt either would play a good role in developing a new socialist project.