What’s wrong with the Keynesian answer to austerity?

As austerity measures bite while the economy continues to flatline, arguments for a Keynesian response to the recession are gaining traction. Marxist economist Michael Roberts casts a critical eye over the Keynesian case, arguing that it misunderstands the causes of capitalist crisis

As austerity measures bite while the economy continues to flatline, arguments for a Keynesian response to the recession are gaining traction. Marxist economist Michael Roberts casts a critical eye over the Keynesian case, arguing that it misunderstands the causes of capitalist crisis

A new radical think-tank kicked off last year in the UK. It’s got a great name: Class: the Centre for Labour and Social Studies. Sounds socialist, even Marxist, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, at its first meeting the speakers, especially the economists, were all Keynesians. All the arguments against austerity were Keynesian. Apparently, a Marxist analysis has no contribution to make in explaining the Great Recession and the ensuing long depression – or what to do about it.I think it is a serious deficiency for those fighting for labour against capital, and needing to find the right policies, to rely on Keynesian theory and policy.

Why do I say that? Well, let me start with the kernel of Keynes’s contribution to economics: his emphasis on the macro economy. Keynes wanted us to focus on the macro economy through his key national accounting “identities”. National income = national expenditure – that’s easy. National income can then be broken down to Profit + Wages; and national expenditure can be broken down to Investment + Consumption. So Profit + Wages = Investment + Consumption. Now if we assume that wages are all spent on consumption and not saved, then Profits = Investment.But here is the rub. This identity does not tell us the causal direction that can help us develop a theory. For Keynes, the causal direction is simply that investment creates profit. But what causes investment? Well, the subjective decisions of individual entrepreneurs. What influences their decisions? Well, “animal spirits”, or varying expectations of a return on investment, etc. It is entirely subjective.

Back to front

In any case, the idea that profits depend on investment is back to front. For Marxists, it is the other way round: investment depends on profit – and profit depends on the exploitation of labour power and its appropriation by capital. Thus we have an objective causal analysis based on a specific form of class society, not based on some mystical psychoanalysis of individual human behaviour.

Now if investment in an economy depends on profits, and if profits are fixed in the equation and cannot be increased, then investment cannot be increased. So capitalist investment (ie investment for a profit) will now depend on reducing the siphoning off of profits into capitalist consumption and/or on restricting non-capitalist investment, namely government investment. So capitalism needs more government saving, not more spending. It is the opposite of the Keynesian policy conclusion. Government spending will not boost profits, but the opposite – and profits are what matters under capitalism. So government spending is a negative for capitalist investment.

But the Keynesians do not consider profit. They look at output. They argue that, for every change in government spending in an economy, there is a corresponding change in consumption and national output. So if government spending is cut, there will a reduction in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of some amount. This is the so-called fiscal multiplier. And it is powerful, according to the Keynesians.

As the world’s leading Keynesian guru, Paul Krugman, put it in his blog, “I and others have been arguing for a while that the experience of austerity in the eurozone clearly suggests pretty big Keynesian effects.” The International Monetary Fund (IMF) agrees, according to the evidence of the graph below. It shows that the more government spending cuts are made by a government (Greece – 16%), the worse is the decline in real GDP (Greece – 19%).

Indeed, this idea has now been latched onto by the Trades Union Congress (TUC). The TUC calculates that the UK fiscal multiplier is as high as 1.3 – the middle of the IMF’s new range – so the government’s fiscal cuts have reduced UK real GDP by two percent since 2010

But hold on. Before we bow down before the Keynesian multiplier, consider a couple of issues. First, is the IMF evidence that conclusive?

Well, not according to a Financial Times (FT) analysis. As the paper put it, “An exercise by the Financial Times to replicate and evaluate the IMF’s work, however, showed that the results suggesting very large multipliers – the relationship between deficit reduction efforts and growth – do not easily stand up to a different choice of countries or time period.” The FT goes on, “For the countries where the full data are available on the IMF website, the results lose statistical significance if Greece and Germany are excluded. Moreover, the results were presented as general but are limited to the specific time period chosen. The 2010 forecasts of deficits were not good predictors of errors in growth forecasts for 2010 or 2011 when the years were analysed individually. Its 2011 forecasts were not good predictors of anything.”

And when we go back and analyse previous estimates of the Keynesian multipliers, we find that the fiscal multipliers vary widely if the time periods are altered. Indeed, the IMF notes in its report that “earlier analysis by the IMF staff suggests that on average fiscal multiplier were near 0.5 in advanced economies during the three decades leading up to 2009.” That means boosting or cutting government spending and taxes had little impact on growth during those years.

Causation

But then there is another issue: causation. These studies do not tell you what causes what. Did the recession cause deficits to rise and debt to increase and thus force governments into austerity, or the other way round? Surely, it was not fiscal austerity that caused the Great Recession, but the Great Recession that led to fiscal austerity. Krugman’s reply is rather unconvincing – namely that, as the IMF got it wrong and the impact of government spending cuts has been worse than expected, this shows that austerity must be the cause and slowing growth or contracting economies are the result.

Well, there has been a heap of studies that argue the contrary: that it is large budget deficits and high debt that will cause GDP growth to falter. The most famous one is by Reinhart and Rogoff. It shows that if public debt levels get to over 85 to 90 percent of GDP (as they now are in most advanced capitalist economies), then it can take years (five to seven years or more) to restore “normal” economic growth. The implication is that the quicker public debt ratios are reduced, the quicker the sustained growth can resume.

But the causation is not clear: 1) a recession causes high debt, so the only way to get debt down is to boost growth (Keynesian) or 2) high debt causes recessions, so the only way to restore growth is to cut debt (Austerian). The evidence one or way or another from all these studies is not there.

I did a little piece of statistical research on this issue comparing the average budget deficit to GDP for Japan, the US and the euro area against real GDP growth since 1998. 1998 is the date that most economists argue was the point when the Japanese authorities went for broke with Keynesian-type government spending policies designed to restore economic growth. Did it work?

Well, between 1998 and 2007 Japan’s average budget deficit was 6.9 percent of GDP, while real GDP growth averaged just 1 percent. In the same period the US budget deficit was just two percent of GDP, less than one third of that of Japan, but real GDP growth was three percent a year, or three times as fast as Japan. In the euro area the budget deficit was even lower at 1.9 percent of GDP, but real GDP growth still averaged 2.3 percent a year, or more than twice that of Japan. So the Keynesian multiplier did not seem to do its job in Japan over a ten-year period. Again, in the credit boom period of 2002-07, Japan’s average real GDP growth was the lowest even though its budget deficit was way higher than the US or the eurozone.

The Keynesian multiplier measures the impact of more or less spending (demand) on income (GDP). But there is a Marxist multiplier. Here the causation is from profits to capitalist investment and then from investment to employment, wages and consumption. Spending and growth in GDP are dependent variables on profitability of investment, not the other way round. The Marxist multiplier measures changes in profitability and thus their impact on investment and growth.

Profitability

If the Marxist multiplier is the right way to view the modern economy, then what follows is that government spending and tax increases or cuts must be viewed from whether they boost or reduce profitability. If they do not, then any short-term boost to GDP from more government spending will only be at the expense of a lengthier period of low growth and an eventual return to recession.

If more government spending goes mainly into social transfers and welfare, that will cut profitability, as it is a cost to the capitalist sector and adds no new value to the economy. If it goes mainly into public services like education and health (human capital), it may help to raise the productivity of labour over time, but it won’t help profitability. If it goes mainly into government investment in infrastructure, it may boost profitability for those capitalist sectors getting the contracts, but if it is paid for by higher taxes on profits, there is no gain overall. And even if it is financed by taxes on wages or cuts in other spending it will only raise overall profitability if it goes into sectors with a lower ratio of capital to labour (not usual in infrastructure projects, and if it is financed by more borrowing, profitability will constrained by rising interest rates. So there is no assurance that more spending means more profitability – quite the contrary.

The Marxist forecast

Now let’s look at the same period that I covered above for the impact on growth of the Keynesian multiplier, from the point of view of the Marxist multiplier. After 1997 the rate of profit in most of the advanced capitalist world began to decline. The Marxist multiplier would then forecast that investment growth would start to slow and so would GDP growth. Well, in the four years from 1998 to the mild recession of 2001 US real investment growth averaged 6.1 percent a year, while the government ran a small budget surplus and real GDP growth was 3.6 percent a year. But after the recession of 2001, during the credit boom of 2002-7, US real investment growth slowed to 2.2 percent a year, but the government ran a budget deficit that averaged 3.6 percent of GDP and real GDP growth slowed to 2.6 percent a year. It was the same story for Europe.

Even more revealing is capitalist investment in the productive sectors of the economy (real non-residential private capital formation in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) terms). Between 1998 and 2001, US real investment in productive sectors rose 7.2 percent a year, but from 2001 to 2007 it rose only 3.5 percent a year (half the rate). Again it was the same story for Europe.

There does not seem to be any evidence that bigger government spending or wider budget deficits will lead to faster investment or economic growth over time in capitalist economies. Indeed, the evidence is to the contrary much of the time. The Marxist multiplier of profitability and investment seems more convincing.

Don’t get me wrong. This does not mean austerity is the right policy. The recent suggestion by the IMF director general Christine Lagarde (salary $470,000 per year and no tax) that austerity has worked, by citing the likes of Latvia and Estonia, is so much bunkum. These very small capitalist states in Eastern Europe have done a little better because they received huge fiscal transfers, way more than Greece (see the comments of the IMF’s chief economist and semi-Keynesian, Olivier Planchard). Around 20 percent of Estonia’s budget is made up of EU funding. No banks were bailed out because they are owned by Sweden and other Nordic banks and their exports are heavily oriented towards Scandinavia, which has generally fared much better. And government debt was never high in the first place.

What really helped these economies turn around, such as they have done, was not fiscal austerity, but the destruction of labour rights to allow employers to boost profits and emigration. A sizeable proportion of the Baltic people have left their homelands to find work in the rest of Europe. Skilled workers have disappeared. Latvia has undergone a demographic collapse. Young Latvians have fled the country. In 1991 the population was 2.7 million. The most recent census shows the population has dropped to two million, but is probably lower because of continuing emigration.

The UK government is sticking with austerity and it is not working. But austerity is not the only, or even the main, cause of the UK’s stagnating economy. One recent study found that the relatively tougher fiscal adjustment in the UK compared to the US has contributed slightly less than half the 5 percent point difference in real GDP growth between the two countries over the last three years . The real cause is the failure of the “rentier” economy that is British capitalism. Productivity in productive sectors of the economy is stagnant and investment has collapsed. Holders of capital are accumulating cash, sending it abroad or buying financial assets. But they are not investing. So the real economy stagnates and the authorities can do nothing about it because the capitalist sector dominates.

Steady decline

The reason that UK companies are not investing at home is that corporate profitability is still well below its peak in 2007 and, even more significant, the rate of profit in the productive sector of the economy, manufacturing, continues its steady decline from 1997, and is now hitting lows not seen since the recession of the early 1990s.

Not surprisingly, UK companies are on an investment strike.

So what is the correct policy response to the long depression? A Marxist analysis, in my opinion, recognises that the underlying cause of the crisis in the first place is to be found in the failure of capitalist production to generate enough profit. Then, until capitalism can destroy enough old or “dead” capital (employees, old technology and unprofitable weaker capitalist enterprises) to restore profitability and start the whole thing again, it will languish. In this long depression I reckon this may well require another big slump.

Keynesian-style government spending programmes can alleviate some of the pain for labour and government investment can help create new jobs. This will not boost profitability, but instead will be at its expense. And as long as capitalism is the dominant form of social production, that will mean more government spending will delay the capitalist recovery, not speed it up. If we want to end the long depression and avoid another big slump, we need to end the capitalist mode of production and replace it with democratically controlled, planned social production.

published with the permission of the author and thanks to Mark Thomas of Socialist Review for putting us in touch with Michael

16 comments

16 responses to “What’s wrong with the Keynesian answer to austerity?”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

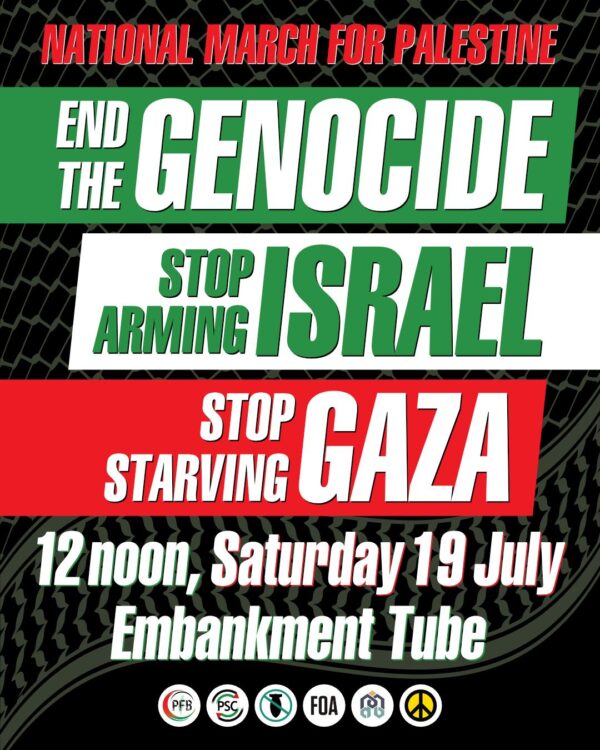

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

This contribution sets out quite clearly why we need Marxism to understand the nature of capitalism & its crises & not fall for Keynesian, social democracy.

Capitalism cannot afford social democracy. We need class struggle. We need a revolution to rid humanity of the horror of capitalism.

I hope Left Unity is brave enough to be revolutionary.

A Keynesian approach would do a lot in shifting the economic position of the countries policy, and therefore make a move toward socialism less radical and much easier.

An excellent article from Michael Roberts. I had already re-posted this on my own Facebook page. These are the economic arguments we need to discuss and debate. While fighting tooth and nail to defend our class against austerity we need a policy for the complete transformation of society, not policies that try to manage capitalism. Far too many on the left seem set on trying to implement a policy that aims to keep capitalism in place. As Michael points out, Keynesian policies can’t do what they aim to do anyway. We should set out to change the world. Anything less won’t work.

An excellent analysis. The big Keynesian mistake is that it assumes that capital relies upon the spending power of workers and governments to sustain profits. The logic being that there would be a glut of unsold commodities if wages and public budgets went too low. True to a point, but different sectors of capital invest in different commodities with different markets. Tescos relies more on people’s spending power than BAE systems – who depend on government consumption. But – sticking to arms – the consumption of much of the UK’s manufactured armaments is by overseas governments, so defence cuts here don’t have an impact if there are growing markets in say – Saudi Arabia. The same goes for much of the productive sector and the luxury sector. This means that workers’ and governments’ spending power is not an invariant, and that Keynes – and Keynesian parties – lack an explanation for this.

Some revolutionary communists have told me that Keynesianism, tax justice, charity, redistribution, welfare and the like are just pain killers while the underlying tumour of capitalism remains. That may be true, but while the poorest, most vulnerable people of this country are sitting on the long waiting list for surgery, I would like to relieve as much of their pain as possible. I have always been a Marxist and have always set out to change the world. But to ignore the little victories of Keynesianism in the short-term seems to me inhumane.

This is a critical issue you raise, Salman. Whilst not for a moment challenging the veracity of the Marxist economic analysis presented so concisely by Michael Roberts, its conclusions , if adopted too rigidly, are a real tactical and policy problem for a radical socialist party wanting to offer anti austerity policies which can be easily understood by everyday people and offer realisable, “solutions” in a reasonable timescale.

The huge problem with the (quite correct) Marxist economic analysis is that it coincides exactly in key areas with the analysis of the capitalist class itself vis a vis the negative impact on profitability of most government spending, and welfare payments. Of course the Marxist answer is “this proves that until capitalism is overthrown, there is no route to prosperity and general rising living standards” . To which the committed capitalist commentator will reply “thanks for destroying the reformist Keynsian arguments , and since you’re never going to get your socialist revolution, you are confirming the viability of our austerity arguments in the real world !” Not much of a “radical socialist offer to the general public is it ? ie .. It’s full on socialist revolution — or essentially going along with austerity !” The public will choose the “devil they know”.

It’s like going along to a picket line outside a factory , on strike for better wages, and saying “comrades, wage labour merely reproduces your wage slavery … you are wasting your time .. you need to overthrow the capitalist system , not engage in this economistic waste of time !” It wouldn’t go down well would it !

It is quite true tht Keynsian economic policies cannot in themselves “solve” the capitalist crisis of long term faling rates of profit . Only the destruction of huge amounts of existing dead capital and a radical systemic takeoff on a new (as yet undiscovered) wave of technological development (as happened during WWII and post 1945) can do that. However, the struggle to build millions of council houses with all the resulting job opportunities, the struggle to defend NHS and Welfare spending – the struggle generally against the austerity offensive is perfectly justifyable simply because it is in a context of “us”, the majority, refusing to pay for “their” (the capitalist superrich class) crisis. Anyway, not all the profits going to the capitalist class are directed to investment; a huge amount is devoted to conspicuous luxury goods consumption. In fact over the last 30 years there has been a major realignment of world production sectors to serve this ever rising luxury goods sector. So effective working class resistance , through wage rises and higher taxation of the superrich, can skew part of this luxury goods sector consumption spending back to spending on the Health service, and working class living standards generally, without impacting on productive investment levels at all.

We will get nowhere by denouncing reformist “Keynsian” public works “New Deal” type programmes. People want what such programmes can offer , or promise, ie, jobs and wages. A radical socialist party has to continue to demand Welfare and job creation and social infrastructure-development spending , whilst being careful to always say that this IS just a temporary “sticking plaster” amelioration of the crisis capitalism is in – and that the real solution is a socialist society. The struggle itself, merely actively opposing the austerity agenda, will, if carried out on a mass scale, raise the core issue of capitalism versus socialism – in the form of the direct physical and ideological battle between the majority and the bosses trying to enforce their, profitability restoring, wage and welfare and employment rights cuts. We must not retreat behind a highly theoretical barricade of absolutist “only revolution will achieve anything” positions”. Noone will be listening. As Salman rightly says, we need to aim for lots of “small victories”, and short term betterment (or at least opposing constant further deterioration) of people’s lives, before we have any chance of mobilising masses of people for the final confrontation with capitalism.

I’m afraid you are missing the point. If Marxism is correct, then Keynesianism is an obstacle to getting to the truth. No one opposes reforms, regardless of whether the profiteering parasites can afford them or not That is the point of transitional demands. They are the bridge between the stable post-capitalist future and the consciousness of the masses who know what they think they deserve. We may know that capitalism cannot afford such reforms, nor even the legacy of past struggles. Experience of struggle will prove whether we are right about that or not. Then the majority of workers start to move to the next step: removing the veto from the propertied classes. Then it becomes no longer a question of borrowing, but of radical redistribution through wealth taxes as well as income tax. As far as charity is concerned, there is nothing to be said for that other than it is a tool for the super-rich to pose as better than the rest of us because they have more spare cash, and they flaunt their ‘generosity’, expecting thanks that some of their ill-gotten gains is invested in cheap pubic relations as well as mansions and butlers. As far as borrowing is concerned, the markets will crash if any so-called social democratic government tries to implement reforms the capitalists do not like.

I’m a bit concerned how the most recent contributions to the main site are panning out:, now I think L/U is a very very positive initiative, political theory has its place an no one wants to proscribe what is being discussed but its starting to look like political manoeuvring by the committed Marxists to capture the emergent movement/party is beginning: the front page now has a dry economic article on marxist economics and a critical review of the 45 reforms, Poseters bringing out the old “reform vs revolution” argument in all the btl spaces, etc. In other places, the SWP have said they want to ‘win the arguments’ on LU etc,

Imo; from what I’ve read, most of the new membership come across as left libertarians, or even the old ILP, I really don’t want to see the old time strategies where one sees old school marxists who engage in waiting out the newcomers who become bored and disillusioned. I can’t know for certain but like Salman above I suspect most people joined to defend/work alongside the most vulnerable, and challenge austerity, not have long winded debates which the wider population would be baffled by.

The LU phenomemeon(sic) is an exciting and refreshing one, I thought quite a long time before posting this, I don’t want to upset any equilibrium/drive for moving forward, and I really hope I am wrong, but these hard times and the suffering are too important for egos, agendas and that includes those from other political strands, greens, anarchist, me, etc..

Jonno, there is indeed a balance to be drawn. We mustn’t be ideological pure & insist on revolution or nothing. That is not a Bolshevik position, as they are keen on united fronts (working with non-revolutionary workers), but it is sometimes a libertarian communist position (I say that as someone who identifies with this tradition). We should promote reforms that can lead to more revolutionary demands, this can include more government spending on things that benefit workers as opposed to government’s buying up banks bad debt. But in the context of this & similar articles where we are talking about the accuracy of economic theory, we should be clear that Keynesianism cannot explain capitalist crises, let alone cure them. Keynes fell back on the subjective notion of ‘animal spirits’ explaining why capitalists hoarded money instead of investing. He had to do this because his economic theory is based upon a subjective notion of value – marginalism. Marxism has the advantage of an objective theory of value. It can explain the nature of this crisis & pass capitalist crises, as Michael Roberts himself has done (whilst I still recognise that Marxists aren’t united in their theories of crisis – it is after all a very difficult subject). But we don’t throw away this key theoretical lead just because some are uncomfortable with how some Marxists organise. The Bolshevik ‘democratic centralism’ is often far from democratic as recent events in the SWP have demonstrated. But that’s an entirely different matter. Joseph Choonara, the SWP’s main economic theorist, is very close to Michael Roberts explanation, as I am. But that doesn’t make me a Bolshevik. It does seem that Keynesianism is a more comfortable place for those who are really social democrats (who want a fairer capitalism). Well, we’ll work with you in demanding reforms that will lead to more revolutionary demands, but we will also expose those who are not really socialists seeking an end to capitalism.

I would say contributions to the site don’t necessarily reflect the views of Left Unity as a movement, only the views of the individual author and a commitment from the editors of this site to open debate. Personally, I’m fine with theory being discussed as long as we are united in action where it matters to people’s lives. And that for me certainly means winning the little victories and protecting the most vulnerable here and now.

Jonno, I hope a new radical Left movement which we hope Left Unity can become , will have a wideranging, open, and invigorating intellectual life, as well as a vigorous radical campaigning life. This broad intellectual sweep will obviously encompass the old, but still very relevant, debates about “reform versus revolution”, and debates about the applicability of “Keynsian” analysis and economic “solutions” to the current worldwide capitalist crisis. There are indeed already a broad range of political backgrounds amongst the 7,000 or so who have already indicated interest in Left Unity from the postings so far aired. Free and open debate is surely the heartblood of an open dynamic radical movement ? You seem to be hostile to the current range of the debates ? Surely, if a new radical party of the Left is to engage in useful political ACTION, it has to debate the underlying ideas and theories which dictate and guide what priorities and directions our future political action should take ?

I thought the review of Ken Loach’s film was very balanced and fair. The review , as indeed the film itself, points out that the Attlee governments reforms were possible because of the massive popular will for a better postwar society. But the implementation was structured in the context of making capitalism work more efficiently in the war-ravaged postwar world – as well as improving the living conditions of the majority in the British Empire’s metropolitan heartland (the NHS and welfare reforms weren’t offered to the colonies). It is simply the case that all of the reforms of the 1945 Labour government have either already been reversed (privatisation of pretty much ALL of the industries nationalised ), or are about to be destroyed and/or privatised (the NHS, the Welfare State generally). This underlines the key point for a radical socialist movement seeking to go beyond Labourite reformism – that as long as capitalism continues, all reforms achieved can be reversed. This was inconceivable to radical Labour reformers in 1945 – who saw their reforms as permanent and cumulative. We now know differently. We can therefore not aim to simply rebuild an “old style” Labour Party. We must build an open , democratic, activist party prepared to take on the capitalist austerity offensive without reserve, but also one that recognises that “socialism” is a much more radical transformation process than nationalising a few industries and introducing a few (though massively important for people’s lives) welfare reforms – whilst leaving the capitalist power structures in place.

A marxist critique of Keynesian economics needs to deal with the climate/ecological crisis and the role of “growth” in that.

Salman “…contributions to the site don’t necessarily reflect the views of Left Unity as a movement”

A bit of a premature disclaimer, surely?

Left Unity hasn’t even agreed on what its “views as a movement” are yet. So at this point, one person’s views are just as valid as any another’s.

The problems usually occur when decisions have to be made, votes taken and then acted upon.

Trying to exclude the existing parties of the left, their members, or their ideas from something called “Left Unity” would be a strange thing to do.

Politics abhors a vaccuum.

btw, I like Michael Roberts critique of Keynesianism. He has said that a United Front between left-Keynesians and Marxists is desireable.

So what’s not to like?

Ummmm… I’m not a Marxist (although I have tried, really I have) but can I make an economic point.

Keynes’s major contribution was to define the field of macroeconomics and to show how different rules were in operation at the meta-level in a cash economy. The Marxist story of declining profits as presented by Michael Roberts appears to be merely standard microeconomic theory writ large.

PS there are two policy options available that would chime with a Marxist analysis and have proved successful in the current crisis. These policy options are free in terms of cost to the Government and have worked successfully in the US (note: we are allowed to take the best bits from any system!).

They are: 1) amending property law so homeowners can just walk away when they are financially under water (isn’t that why the property itself is meant to be security?); and 2) rent controls linked to the average wage to ensure social justice and avoid creating ghettos (a lesson we were meant to have already learned!).

PPS I currently despise the fact that all 3 parties seem committed to keeping house prices high in order to “save” the economy. How can a policy that guarantees slow growth for a decade and adversely affects the youngest and oldest in our society face almost no political opposition?

PPPS are Marxists economists ducking the challenge of promoting meaningful change if their only active policy insight is… we need a Marxist revolution?

A debate about the crisis of British capitalism has to start with its peculiar characteristics. Britain remains the second imperialist power in the world today measured by extent of overseas assets – £10 trillion, 6-7 times GDP. Despite rising challenges, the City of London remains the world’s leading financial centre: it is the heart of British imperialism. Parasitism is its essence: British imperialism has maintained its position through its ruthless financial plunder of the world. Why does the left ignore this? Discussion of the falling rate of profit is old hat: the crisis of over-accumulation expressed itself in the 1970s, and what became described as neo-liberalism was the response, and with it, the re-emergence of inter-imperialist rivalries. Neo-liberalism failed to restore profit rates because the degree to which it shifted the balance of class forces against the working class internationally (although enormous) was inadequate.

The ruling class debate about Europe has now re-opened: there is no longer a possibility of British imperialism surviving as an independent imperialist power: its dependency on banking and financial services makes it extremely vulnerable to shocks in the world’s financial system. And there is no way that Europe (German and French imperialism) will allow the City to survive as an offshore financial centre if Britain withdraws from the EU. How these rivalries play out in the coming period will be vital for politics in this country.

Linked to this is the debate about whether austerity is working. This if course depends on the measure we use. If the measure is economic recovery then clearly it is failing. But the measure is inadequate. The purpose of austerity is to execute that fundamental shift in the balance of class forces against the working class which has been the goal of the ruling class since the 1970s. The extent to which the ruling class achieves it is the true measure of the success or otherwise of austerity. At the moment, it is succeeding: the working class is being massively impoverished, whilst the ruling class is accumulating evermore wealth. It is succeeding because the Labour Party is colluding with the assault, and the trade unions refuse to provide any opposition. New forms of working class organisation are needed, and it is possible that the small community-based groups emerging to fight against the bedroom tax represent just that.