What’s the alternative?

The citizen’s income is a policy that could unite Left Unity, and put us on the road to socialism, says Stuart Watkins of the Leamington Spa group

The citizen’s income is a policy that could unite Left Unity, and put us on the road to socialism, says Stuart Watkins of the Leamington Spa group

If one thing is certain it is that, when Left Unity is formally established in November, the new party will be an explicitly socialist one. The debate about precisely what kind of party we want goes on, but all sides seem to agree on that much. Good.

The real difficulties do not of course end there but begin. Just what exactly do we mean by socialism? And how exactly is it to be achieved? The Socialist Platform believes that such questions should be settled in advance. The Left Party Platform, which I support, believes they should be left open. But whatever happens in November, the new party will face the same problem – how do we come up with policies that a majority can agree upon, and that can unite the party rather than divide it, given that those brought together in Left Unity have such different ideas about such seemingly fundamental issues?

Get creative

It is this question that leads various leftist grumps and Nostradamuses to predict that Left Unity is heading for disaster. But those who have had some experience of Occupy-style decision-making might instead be excited by the possibilities. We don’t have to pick a side and fight to the death. Instead, we could do some creative thinking. What kinds of policies can we make, what kinds of actions can we take, that will unite us and take us forward to achieving common goals, while outraging no one? After all, the seriousness and scale and importance of the problems we face and the need for us to unite and take action far outweigh the importance of our differences over intellectual matters. Our nascent party has already brought together – to take just two examples – revolutionary socialists who demand nothing short of the complete and immediate overthrow of private property and capitalism, with left-of-Labour socialists who propose relatively minor changes to the tax system. The difficulty is not the differences of opinion – any conceivable broad party of the left will have to tolerate these – but the creative challenge in finding action and policy that can unite both.

I’m not of course expecting that my argument here will achieve such a fantastic result. If achievable, that could only be the outcome of much collective discussion and decision-making. But I hope to make a case that such a thing is at least conceivable.

What is socialism?

As stated above, Left Unity’s various factions are already united in wanting to establish an explicitly socialist party. That would seem, then, to be a good place to start. What is socialism? Is there a core meaning in the term or in the history of its practice that could be said to unite all socialists? My answer is yes, and the clue’s in the title. The core meaning of socialism is the social (social-ist) or communal (commun-ist) ownership of the means of production and distribution. As the Left Party Platform puts it, it is a vision where “[t]he natural wealth, productive resources and social means of existence will be owned in common and democratically run by and for the people as a whole”. Or, as the Socialist Platform puts it, socialism “means a society in which the wealth and the means of production are no longer in private hands but are owned in common”. Or, as the Class Struggle Platform puts it, it is “a publicly-owned economy, democratically managed and planned by those who work and those who use its goods and services”. Or, as the proposal to replace the platforms with a set of principles puts it, the socialist aim is to “enlarge common ownership, co-operative models and public-sector provision and diversify their forms”. So, we’re agreed that we’re socialist, and we’re agreed what it means. So far, so good!

What is to be done?

The trouble is that, as surely everyone must also agree, this is an aim for the medium- to long-term. It is just inconceivable that it could be achieved without a mass party with mass support and mass participation – and we’re a way from that yet. It is possible of course for circumstances to change so rapidly that, on a historical scale, we could see socialism established after a revolution that takes place in the blink of an eye. But, on the scale of individual lives and our own political practice, we’re still faced with the problem of what socialists can do right now, in a cultural context that is basically unanimously agreed that socialism, or even relatively mild forms of resistance, are obsolete, or futile, and that there is any way no alternative. The situation is maybe not quite as bleak as I’ve just made it sound: the tide is beginning to turn. Probably. But we shouldn’t nevertheless underestimate the scale of the problem. People generally are not socialists, and are not likely to become socialists, and may even be hostile to socialism (for, let’s face it, pretty good reasons). People generally are also nervous of militant action – again, often for good reasons: to survive in this society at all, people need to build good if often subservient relations with an employer or a breadwinner or with the state bureaucracy. They will not put that at risk for wild adventurism or pie-in-the-sky. Of course not. Who would?

The question then remains: what kinds of things can socialists do that might begin to change this? The obvious answers, which would probably also win majority agreement among socialists, are these: we fight for immediate gains that would benefit the working class and organise opposition to attacks; we try to make participation in organised politics a more attractive option than the telly (some way to go there, haven’t we?); we contest the dominant ideas which make capitalism seem natural and inevitable, and resistance futile, and socialism impossible; and we demonstrate the relevance of socialism and socialist activity to the needs and aspirations of the majority. But as a political party that will almost certainly contest elections, we also need immediately realisable policies that could achieve socialist aims, promote working-class interests, and yet not split the party into mutually hostile factions.

What fits the bill? The policy debate in Left Unity has begun and will no doubt continue in earnest after our November conference. But the policy that springs immediately to my mind is one that is already edging its way into the national conversation: the citizen’s income.

To each according to need

Why the citizen’s income? Let’s go back to the definition of socialism given above. Just what is the point of trying to put the means of production – the factories, the mines, the telecoms companies, the railways, etc – under social ownership and control? The issue is one of slavery – wage-slavery. Under slavery, the worker is sold, body and soul, to the master. Under wage-slavery, the worker is rented out by the hour to the capitalist. Much is changed in the transformation of course, but the basic relationship is not: it leaves unachieved the liberal, capitalist (and socialist) ideal of freely associated individuals engaging in freely self-determined economic activity. A capitalist, it is true, is entirely free to take on a worker or not. A worker, it is true, is theoretically just as free to accept the job or not. But practically speaking, anyone who actually is a worker will know that the ‘free’ choice is somewhat constrained by economic necessity. All too often, we take a job because we must, and are fearful of losing it, no matter how hateful or tyrannical it may become. Socialism is then all about the achievement of the liberal ideal: the end of slavery, the end of political and social and economic tyrannies of all kinds, and the achievement of a community of freely associated producers. A necessary condition for achieving this must clearly be to take power out of the hands of the rich and the bosses and the state and put it into the hands of the community, democratically organised. And given that the source of the bosses’ power is ultimately their ownership of the means of living, we must take ownership and control of those means out of private hands and take them into public ownership.

That’s the theory. How has it worked out in history, in practice? Well, anyone hostile to socialism, or any socialist with a modicum of critical awareness, would be able to tell you the answer. Let’s put it mildly: there have been problems. Putting industry under state control tends to concentrate economic power in the hands of a new bureaucratic ruling class without changing the fundamental economic relationships or getting rid of the problems. Attempts to abolish or circumscribe the market can leave unsolved questions of economic coordination and efficiency, or put them in the hands of (inevitably) clueless bureaucrats pursuing their own, rather than the public, interest – with disastrous consequences. Welfare states represent huge investments in the workforce that capitalists will eventually baulk at paying. And so on. This list could be massively expanded, but even if expanded, the objections would not be decisive for me. I would not be a socialist at all if they were. But they must be reckoned with. Not just in theory, or in debate, or by squabbling about them. If these issues could be solved in that way, then they surely would have been by now. They must be reckoned with by acknowledging them and understanding them and learning from them – and by doing things differently.

Consider now another kind of ‘actually existing communism’ – that which has been called in the Marxist tradition ‘primitive communism’, the kind of communism that exists in hunter-gatherer tribes, and the kind that, as the anthropologist David Graeber points out, actually exists in some form in all societies, even our own capitalist ones. Here, the organising economic principle is ‘from each according to ability, to each according to need’. In other words, you contribute as you can to your community, but, as a member of that community, you can expect to have your needs for food and shelter and so on met, as of right. So, in the classic account of the Iroquois Indians, penned by Lewis Henry Morgan and made the basis of Engels’s Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, you find that economic resources and what we would call consumer goods are held in common in storehouses, and distributed according to need. More modern accounts show hunter-gatherers simply helping themselves if they consider that an individual has accumulated more than his fair share of, say, food. To bring things closer to home, in a capitalist factory or office, if you need a spanner or supplies from the stationery cupboard, you take them – you’re not charged by the hour. In the family, one does not normally padlock the fridge. As Graeber points out, the principle here is certainly ‘communist’, but is not actually, not necessarily, one of social ownership and control of the means of production – it’s more a moral principle of consumption. It’s about what you’re entitled to as a member of a given community, regardless of who does or does not claim ownership of the means of production. Which brings us to the citizen’s income.

The citizen’s income

The citizen’s income is simply an income, paid by the state, to every citizen, as a right, and without precondition (other than that of citizenship). It is not means-tested, or dependent on your looking for work, or on proving that you’re capable or willing to work, or indeed on anything else. If you’re a citizen, you get it, and that’s it. In other words, it is something like a communist measure, as defined above, where people get access as of right to what they need – not directly, as might be most communist or ideal, nor because of their ownership or otherwise of the means of production, but anyway via the means of money.

The demand for a citizen’s income has now something of a long history, but it might be an idea whose time has come – it has been discussed in recent times, seriously and without ridicule, in such relatively mainstream publications as the Economist, Financial Times, and Washington Post; it is current Green Party policy; and was seriously considered (if eventually rejected) by the Lib Dems. The policy could even make pretty good sense to conservatives, perhaps even Conservatives, if sold right – not because the proposal is unradical, but because it is increasingly seen as objectively necessary, as an answer to intractable economic problems, including the cost pressures on the welfare state, declining real wages, and the fact that the progress of capitalism tends to mean jobs are increasingly lost to machinery and computers. This piece is already too long, and to go into all the pros and cons of the idea would be to repeat work that has already been competently done elsewhere (see footnotes for some good places to start if you’d like to read more). I will restrict myself here to my remit: to argue that adopting this policy would be a good idea for Left Unity.

The key point to my mind is that the policy could achieve at a stroke the unification we are looking for, ie, could unite the ‘revolutionaries’ and the ‘reformists’ (inverted commas to indicate that I am in want of better, accurate and neutral terms, but believe I’ll be well enough understood if I use them) and also speaks to our short-term aim of opposing austerity, especially as it hits the poorest and most vulnerable in our society.

It will surely please the ‘reformists’ as the policy is so obviously appealing and achievable: the state could realistically implement it tomorrow, arguably with few cost implications, at least in static terms (see Stumbling and Mumbling blog, ‘The Case for Basic Income’, below). At a stroke, it would achieve important left social goals: it would end extreme poverty and the worst inequalities, while, perhaps ironically, doing away with vast and costly layers of the welfare and pensions bureaucracy. Unlike the welfare state even at its best, it would free carers of children or of the sick or disabled from dependence on breadwinners or state bureaucrats, and free the disabled from humiliating tests to determine their fitness for work. It is hence inherently feminist (in our society, it is still mostly women who do the work of caring) and compassionate. It would likewise free the unemployed from the harassment of proving that they don’t work but are willing to. It would free the horribly exploited and overworked and badly paid from their jobs, and end the social stigma of being unemployed or living on benefits, building solidarity among the working class.

It should also please those with more revolutionary long-term aims – and, indeed, conservatives and libertarians genuinely interested in creating a free economy. At a stroke, we would have done away with the worst tyrannies of wage-slavery and instead created something like a genuinely free market in labour, ie, people would take jobs if and only if they wanted to do them or considered that the rewards (monetary or otherwise) outweighed the costs in terms of lost free time. It would give an instant boost to the bargaining power of workers already in jobs, enabling them to stand up to bosses to improve wages and conditions, or push for ownership stakes in their firms, or even take them over completely. It would help small businesses, which could pay low wages and yet still hope to attract people on the basis of the value of the work. We would have more people with more time to engage in the activities proper to a democratic citizenry – holding politicians and everyone else in positions of power or responsibility to account, doing political and trade union and solidarity work, and so on. Entrepreneurs – whether in the usual sense of the term, or what we might call social entrepreneurs, who want to set up co-operatives or social enterprises or campaigns or political parties or engage in voluntary or charity work, or artistic work, or organize more revolutionary changes in their communities, and so on, and so on – would be free to pursue their projects without fear of penury. It would disincentivise work for its own sake and consumerism and promote independent creative activity – is hence, then, also an inherently green measure. And, as an added bonus and useful social experiment to test anti-socialist arguments, all those people who assure us that they want to do nothing but sit on their arses playing computer games all day could do that too, and see if it makes them any happier.

At a minimum, what the citizen’s income would create would be a capitalist society that lives up to its own ideals and that might even conceivably work somewhat better than it does now from being built on a solid ground of healthy communist relations, freedom, genuinely free markets, and the goodwill of its workers. But I hope it’s not hard to see that what we would have is also a kind of ‘transition to socialism’ (see blog below). We would have made a move towards establishing the socialist principle that everyone in society is entitled as of right to what they need. We would also have created the space and the freedom necessary for bigger, more revolutionary changes – in much the same way that Marx considered shorter hours and more holidays and better pay essential stepping stones towards socialism. In other words, the citizen’s income creates something like socialism in the broad, moral economy sense, and lays the foundation for the longer term goal of socialism as it is defined by the core meaning of the term, described above. And it would avoid many of the socialist mistakes of the past by seeking to build revolutionary changes in a socialist direction, not on top-down directives or the premature seizure of state power by a minority, but on the direct and immediate liberation of the working class – freeing us to do something better and more constructive than what the bosses and the state have got lined up. It is a reform for revolution.

There are and will be objections of course – you can find them, and some of the proposed answers, in the links below. Are any decisive? For me, there are two main obvious problems: one political, the other economic. The political objection would be that even this relatively simple and conservative reform is too utopian, too off-the-scale, to be considered as a practical policy for a party seeking election. This may be true, but Left Unity, if it is about anything at all, must be about changing this political reality, reframing the debate on what is conceivable, feasible, politically achievable and economically practical. If it’s not about this, then the whole project is completely worthless. (It’s worth remembering that, even as Thatcher came to power, the economic and social policies that came to be known as Thatcherism were almost universally considered beyond the pale politically, even by the Conservative party as a whole. They became and remain so much a part of the national common sense that people on the whole aren’t even capable of imagining that there could be an alternative any more. This reframing of the debate and of possibilities and the collective imagination was achieved by the work of Thatcherite think tanks and persistent political agitation and battles. It’s not inconceivable that we could achieve similar victories, but for the left.) The economic objection is that the citizen’s income may be incompatible with the continued existence of capitalist society – that, contrary to my hopeful speculation above, the production of profits relies on the existence of a disciplined, flexible yet economically forced labour market, including a reserve army of the unemployed kept in a state of relative misery, and that if this state of affairs is ended, then corporations and private individuals will no longer be able to make profits by exploiting natural resources, including labour, for their own benefit, while keeping everyone else one wage cheque away from desperation. This objection to the citizen’s income may be true – the Marxist in me thinks it almost certainly is. But then, what better reason could socialists have for implementing it?

Further reading

Citizen’s Income Trust: http://www.citizensincome.org/

Basic Income UK: http://basicincome.org.uk/

European Citizens’ Initiative for an Unconditional Basic Income: http://basicincome2013.eu/

The Green Party’s policy: http://policy.greenparty.org.uk/ec

Red Pepper: http://www.redpepper.org.uk/an-income-of-ones-own-the-citizens-income/

Economist Chris Dillow:

- on the case for a basic income: http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2005/04/the_case_for_ba.html

- on the transition to socialism: http://stumblingandmumbling.typepad.com/stumbling_and_mumbling/2013/07/the-transition-to-socialism.html

Some of the arguments in this piece (about the role of socialists) are lifted wholesale from Conrad Lodziak, see: http://bigchieftablets.wordpress.com/old-blogs-home/false-consciousness-are-workers-brainwashed-by-capitalism/

8 comments

8 responses to “What’s the alternative?”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

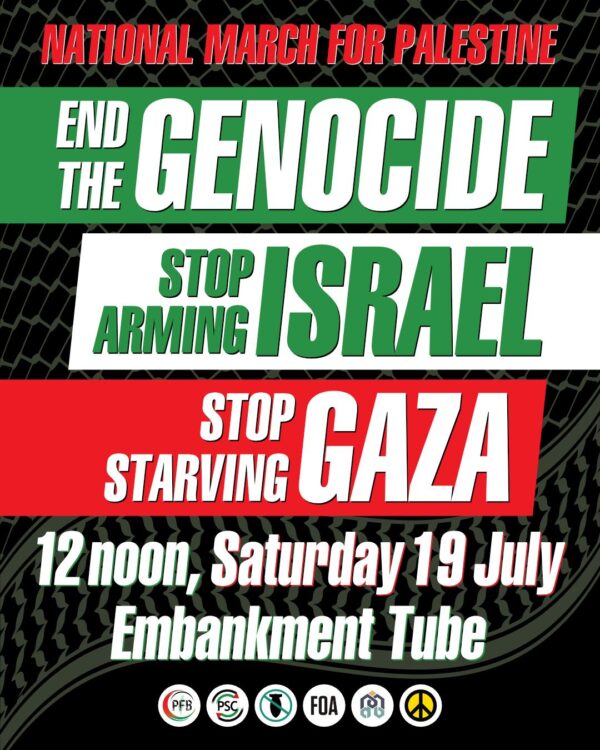

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

A Citizens Income is a genuinely ludicrous idea. I think it is some Green Party policy. What the working class needs is full employment by sharing the available work on the minimum of a living wage. Sitting on their arses being handed a citizens income whilst immigrants are shipped in to do all the work is what the ruling class does.

Stuart, I look forward to your response to the inevitable discussion; I know it’s been less than 24 hrs since you have posted. I read briefly through some of articles you referenced at the end, but not in any great depth. Please, I’ll appreciate any corrections to or referrals from my comments, for I might lack crucial data of which you could fill in.

First, I think you’re absolutely correct that the different tendencies in Left Unity should maintain their unity, despite certain differences and, I’m assuming you’re accurate, I think it should be based on the socialist unity that you are saying has become fundamental to the organization right now.

However, I am critical of the Citizens Income as being the next step in a socialist Left Unity. I’m speaking as an USAer , so perhaps Europe is different. But a question that returns over and again to me is “who is paying the Citizen’s Income?” This is presumably a relatively immediate solution to the problem, so would it be the current state bureaucracy? In each country individually or in the EU as a whole? In either case, I believe immigration would need to become free into and out of the EU, or else there may only be a shift in what part of the global working class that capital is exploiting in Europe. If so, free immigration into and out of Europe would become another point that we need to find socialist unity around. We will also have to consider prison labor for the same reason.

Further, presuming that the bureaucracy could be made accountable, somehow would move funding from the needs of capital to the fulfillment of the Citizens Income (CI), and somehow come to the consensus of what a universal wage might be, an old saying comes to mind: “if the minimum wage is raised, the capitalists will raise their prices”. Your proposal, I know, is not strictly a minimum wage as I know here in the USA because it would be a right maintained by the state. However, as you know, there is still a working class and there is still capital. Capital will have already tried to react through its political clout by trying to keep the CI down. If it somehow failed, it still owns the means of production and sustenance. It can still raise prices to a level that will force me back to work. If, for a simple example, it costs $10 to live fully and the state pays me $10, the capitalists will just start charging $20. If then, the state pays $20, they’ll charge $30.

You can guess what’s next. The only option then, in order to maintain an actual living CI without being subject to the needs of capital, is to somehow forcibly control capital. You will have to force capital to stop or forcibly socialize it. But for that to happen, either the EU politicians will have to have become socialists or there will need to be a EU level working class revolution. Therefore, it would seem that we logically need to unify either on socialized industry or else somehow believe we can live in capitalism while restricting its tendencies. Unifying on that last point you know is a dilemma if some people are still “revolutionaries” and others “reformists”, as you titled them.

That is at least the logic I have used to understand the CI. Please correct me anywhere that I am mistaken; I’d appreciate it.

And in order to not only be deconstructive, but also constructive to the debate, I propose that instead of unifying on economic solutions to solving economic problems, we unify on political solutions to solving economic problems. I’m not in Europe, so I can’t pull out a specific example, but if we’re all socialists here, instead of fundamentally focusing on a Citizen’s Income, we should fundamentally start unifying on means by which fulfilling our needs in an end in itself (basic biological needs, fair and equal representation in decision, respecting individual needs, some local control, I don’t know). From that fundamental, I think, the ideals of the CI will naturally flow, although I understand that you were using it as a unifying point and not a fundamental programmatic principle that we base our system on.

Morally, I agree with you. A CI is a good thing. I just don’t agree that it is a practical, starting, unifying point in the long run.

Thanks Russ and David for your comments, and in advance for any others that arrive. I won’t be replying to any of the criticisms straight away. To be honest, I’m thinking on my feet and learning as I go with this as I have not in the past been an advocate of the citizen’s income (thinking it too utopian for the short term, not utopian enough for the long – but recent reading, including the pieces I linked to, changed my mind). However, I will be making a note of any and all criticisms, and taking them with me for discussion to Left Unity’s policy conference in Manchester, England, on 28 September. I will then try to write that discussion up as a report.

All the best, Stuart

Alright Stuart, hope you and the rest of Left Unity the best at the conference. I’m really looking forward to a positive and useful the outcome.

“[t]he natural wealth, productive resources and social means of existence will be owned in common and democratically run by and for the people as a whole”.

Stuart,

Perhaps I missed this but it is NOT in the LPP as far as I can see.

Can you help!

Hi Ray! It’s in the supporting statement:

http://leftunity.org/towards-a-new-left-party/

PS Wanted to email you or Facebook you after last NCG but couldn’t find you. Email me at stuartrag@yahoo.co.uk? Cheers

Agree with Russ D

“if we’re all socialists here, instead of fundamentally focusing on a Citizen’s Income, we should fundamentally start unifying on means by which fulfilling our needs in an end in itself (basic biological needs, fair and equal representation in decision, respecting individual needs, some local control, I don’t know). From that fundamental, I think, the ideals of the CI will naturally flow”

The ideals are right imv but CI not the means.