What kind of Left do we need?

Award-winning children’s author and campaigner, Alan Gibbons, discusses the way forward for the Left

Award-winning children’s author and campaigner, Alan Gibbons, discusses the way forward for the Left

The world is in crisis. The global economy continues to struggle. The World Bank’s report on Global Economic Prospects manages to argue simultaneously that financial market conditions have improved dramatically since June 2012, but that “the real-side recovery is weak and business conditions low”. It estimates that growth in 2013 will be 2.4%, only marginally above the estimated 2.3% growth for 2012. It estimates that the biggest economy, the US, will grow sluggishly at 1.9% and the UK will continue to bump along the bottom at 1.1%. The state of the Eurozone countries continues to pose a major headache for those who argue that market capitalism is the only game in town. At some point there will be a modest, probably sluggish recovery, but the fundamental problems of capitalism PLC will remain unresolved.

As indicated above, the UK economy is, contrary to the arguments of PM David Cameron and his beleaguered Chancellor George Osborne, in a parlous state. Increasingly, when they try to boast that they have cut the deficit by a quarter (a claim exploded in a recent Channel 4 investigation) and laid the basis for a strong recovery (belied by the state of manufacturing, services and construction) critics circle in however coded a manner. These have included the IMF’s chief economist Olivier Blanchard, Jim O’Neil of Goldman Sachs and the ubiquitous Tory opportunist Boris Johnson. Even these firm apologists of market capitalism think austerity is a busted flush and want to see Plan B or at least Plan A and a half.

It does not follow automatically that the Left should be the immediate beneficiary of this picture of crisis. There is an old adage that a crisis of the system is often simultaneously a crisis of the Left. So it has turned out. In the UK Labour is ahead in the polls, but not convincingly so. There appears to be a widespread vestigial distrust of Labour after the meltdown of the Brown years. Given the multiple catastrophes of the Conservative Party, Labour should be much further ahead in the polls than it is. Labour has enormous problems in Scotland and Ed Balls’ notorious acceptance of cuts and austerity on behalf of the Labour leadership, rather than winning ‘middle England’ appears to be contributing to a sense that it is failing to speak up on behalf of its own traditional base. Cameron’s recent speech on Europe has given him a bounce in the polls which, though likely to be short term and eroded by the UK’s continuing economic woes, has posed problems for UKIP on the right and Labour on the (not so) left.

Labour councils are contributing to the widespread conviction that the party is a whole sackful of compromises short of springboard to power. At a time when living standards are crumbling and the Tories are carrying out an onslaught on public services, Labour councils are acting as a conduit for cuts. Newcastle’s decision to cut its entire Arts budget is only the most notorious symptom of this spinelessness and failure to even try to shield the mass of the population from the Tory axe. A new group, Councilors against the Cuts, is welcome but extremely weak at the time of writing compared to the scale of opposition mounted in the 1980s against a similar Tory offensive. The Left inside the Labour Party, while there are some principled individuals, has very little resonance.

So what of the Left outside the Labour Party? The once moderately strong Communist Party is history. The Morning Star remains with a modest circulation. Respect won a stunning victory in Bradford, causing Ed Miliband to swallow so hard it registered nine on the Richter scale, but George Galloway’s by-election result was followed by controversial comments about rape by the new MP, provoking the exit of Salma Yaqoob and Kate Hudson. For all Galloway’s skills as an orator, it is a party confined to a handful of areas and very dependant on the profile of its best-known member. Tony Mulhearn, veteran Liverpool activist and a member of the Socialist Party, won a significant vote in the city’s Mayoral election, but the party is a shadow of its former incarnation as Militant which was prominent in the Liverpool council crisis of 1984-5 and the poll tax campaign. In Scotland the Tommy Sheridan dispute saw the fracturing of the Left outside Labour, a conflagration from whose ashes it is only now beginning to emerge. The Trade Union and Socialist Coalition’s vote at elections has been tiny and it has never had electoral successes to compare with Galloway’s triumphs. There are various smaller groups, but they have never had much influence.

The most recent self-inflicted disaster to engulf the Left is the car crash over the Socialist Workers Party’s handling of a rape allegation against senior member ‘Comrade Delta.’ This has led to open dissent by well-known members China Mieville and Richard Seymour, the resignation of Socialist Worker journalist Tom Walker, protests by many Socialist Worker Student Society groups and calls for a recall conference to discuss the Central Committee’s conduct of the accusations. This follows hard on the heels of the Respect fiasco when there were briefly two Respects. This conflict led to the emergence of Counterfire, led by former SWP Central Committee members John Rees and Lindsey German.

There is an argument that this fragmentation, disintegration and marginalisation is a product of objective circumstances, the ‘state of the movement’. This seems a dubious line of argument for two reasons: firstly because elsewhere in Europe organisations such as Syriza, Die Linke and the Front de Gauche have had some success in sustaining radical politics outside the social democratic parties, secondly because the far left has, in the recent past, helped build the Stop the War movement, its high point being the two million strong march against the Iraq war. At least part of the explanation has to be subjective, the actions of the leadership of the groups posing as an alternative to the traditional reformist parties. These groups have variously built the Stop the War campaign, the poll tax movement, the miners’ support committees, the Liverpool council campaign in the 80s, the Anti Nazi League and Rock Against Racism. Significant as these achievements have been, it has not translated into any significant growth of the Left outside the Labour Party. The Left that has broadly emerged from Trotskyism has also been much less central in a number of significant movements such as Occupy, UK Uncut, environmentalism, feminist initiatives such as the Slut Walks and LGBT campaigns that have challenged some of its preconceptions. Indeed, the outside Left appears weaker, greyer and less confident and vibrant as evidenced by the picture of marginalisation, splits and internal disagreements. It has struggled to relate to some of the explosive new movements and sometimes labeled them with an element of pejorative dismissiveness ‘autonomist.’ In the case of the SWP its recent difficulties may well be a partial spin off of its retrenchment, retreating from ‘the movements’ and ‘united fronts of a special kind’ to its default setting of party building.

One consequence of the state of the outside Left is that there is not a single movement on the key issue of the day, cuts and austerity. There is the Coalition of Resistance, Unite the Resistance (a successor to the Right to Work Campaign), the National Shop Stewards Movement and UK Uncut. A strong, healthy and coherent movement would surely be capable of uniting in a single body. The recent 25,000 strong LewishamHospital demonstration shows that there is widespread discontent. Disturbingly, at a national level, the second of the TUC’s cuts demonstrations was substantially smaller than the first. A movement which isn’t moving up, which doesn’t appear to be progressing, usually moves down. A number of trade unions such as Unite are undertaking interesting campaigning work and Unison participates in broad organisations such as Speak Up for Libraries, but many activists feel demoralised and under extreme pressure as the cuts bite.

There is a final factor that has to be considered, and this is the nature of party organisation for any body of people attempting to create an alternative to the Labour Party. A lot of the discussion around the SWP’s current problems revolve around the notion of democratic centralism, in Lenin’s formulation: “freedom of discussion, unity of action.” The term democratic centralism has been used to describe regimes in which factions only exist in pre-conference discussions and regimes with permanent factions. It seems to have lately fossilised into a system in which the full time apparatus of the political party exerts a disproportionate control over the membership and stifles free discussion and initiative. Any rethinking of the Left will have to decide if it has any lasting applicability. I will not assemble the usual series of supporting quotes from Marxist theorists. I find that kind of appeal to papal authorities increasingly stale. In circumstances as challenging as those we face socialists and anti-capitalists have to think creatively and work out solutions for themselves. Rigidly applying formulae stricter than those adopted by the Bolsheviks in clandestine conditions seems ludicrous in the age of a mature parliamentary democracy and the internet. Talk of combat parties looks exotic to most and subjects the Left to ridicule. Over-dependence on a centralised, full time party leadership can be a block on the ability of activists to relate to the world around them and act in an independent, self-confident manner.

So where do we go from here when left wing voices like Owen Jones, Laurie Penny and Mark Steel are hugely welcomed by many, but a coherent political force representing the kind of ideas they hold is just not present? I am not casting a rueful look at the Left from outside. I am part of it. I have been a socialist since I was fourteen and a Marxist since my third year at university when I read the Allende pamphlet Chile’s Road to Socialism, Marx’s Capital and Grundrisse and came to the conclusion that the Labour Party was incapable of delivering socialism. That year, 1974, I met the International Socialists and became a tirelessly committed member of the organisation that would become the Socialist Workers Party. For two decades I barely missed a paper sale or a branch meeting.

I served on its National Committee for many years, worked on Socialist Worker with Jim Nichol, Paul Foot, Laurie Flynn and others. I was a full time organiser in Manchester and Liverpool. By the mid to late nineteen eighties I was having serious doubts about the party’s internal life and ability to adapt. I finally left in the 1990s mentioning absurdly over-optimistic perspectives and inner party democracy in my resignation letter.

A telling moment in my genesis was when I was called in front of a panel of CC members and other leading members at which I was accused of syndicalism, being a block to the growth of the Liverpool District and being a ‘yes-man.’ I wasn’t sure how I managed all three, but the accusation of being a yes man hurt because it had more than a scintilla of truth. I had been a student activist, an USDAW shop steward and branch chairman, a President of Knowsley NUT and conference delegate. I had led campaigns against the NF and BNP. In other words outside the party I was considered a militant and free thinker. Inside it I subjected myself meekly to a stifling conformity as did the overwhelming majority of the organisation. That humiliating contradiction got me thinking. I was a socialist before I joined the SWP. I have remained one in the years since I quit. I speak at the Marxism each summer. I spoke twice in support of Tony Mulhearn’s campaign to be elected Mayor of Liverpool. I work in many joint activities with groups on the Left. Do I believe any of them remotely cut the mustard as the kind of organisation needed to challenge Labour on the left? I’m afraid not and I say this with regret. I gave a quarter of a century to the SWP and I find its current travails deeply troubling. It is the largest organisation on the far left and its weakening is hardly something to welcome.

For all the reasons I have given above I believe we urgently need to rethink the Left. In the trade unions, in the campaigns that spring up, in strikes (and we should not that strike days continue to be low and may remain so for some time yet) and social movements there needs to be a much stronger, better coordinated, anti-austerity, socialist, radical, anti-capitalist voice. It has to be open, democratic, undogmatic and capable of reconciling difference. It has to be internationalist, anti-racist, a staunch champion of women’s liberation and LGBT rights. It has to be flexible about organisational forms. This is anathema to some groups on the Left and that probably explains their current woes. It also has to be generous and able to admit that it doesn’t have a monopoly on wisdom.

I don’t pretend to have all the answers. I do think many people like me have begun to ask the right sort of questions. We could have a much more vibrant and relevant Left than we have now, assembled around a number of jointly agreed principles. There are other models than the Leninist vanguard party. Is it possible to bring together a substantial body of socialists and anti capitalists able to intervene in struggles and mount an electoral challenge to Labour? We will only know if we undertake a root and branch discussion that is ready to topple any shibboleth. I do not underestimate the difficulties. There are no left splits from Labour to help construct a new organisation. There is no substantial former Communist grouping to anchor it. Some left organisations would be hostile to such a project. In Europe for every left organisation which has grown there are others such as France’s Anti-Capitalist Party which have gone into crisis. None of this means we should abstain from debating the possibility of a reformation of the Left. Circumstances demand that the large numbers of people disenchanted with the Labour Party but unimpressed by the fragmented state of the Left outside be given an organisational voice.

We are living through contradictory times. On the one hand a broad-based, principled, non-sectarian left of Labour organisation is urgently needed. On the other, past experience (Socialist Alliance, Respect) warns us that the British Left is notoriously fractious and self-harming. One blade of that contradiction weighs much more heavily than the other, however. The point of socialists is to change the world. It would be pointless and probably self-defeating to declare a new party in competition to all the others. A genuinely reinvigorated Left would have to include at least elements of existing organisations, but if the Left we have is not up to the task there has to be an urgent discussion of how to establish one that is.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

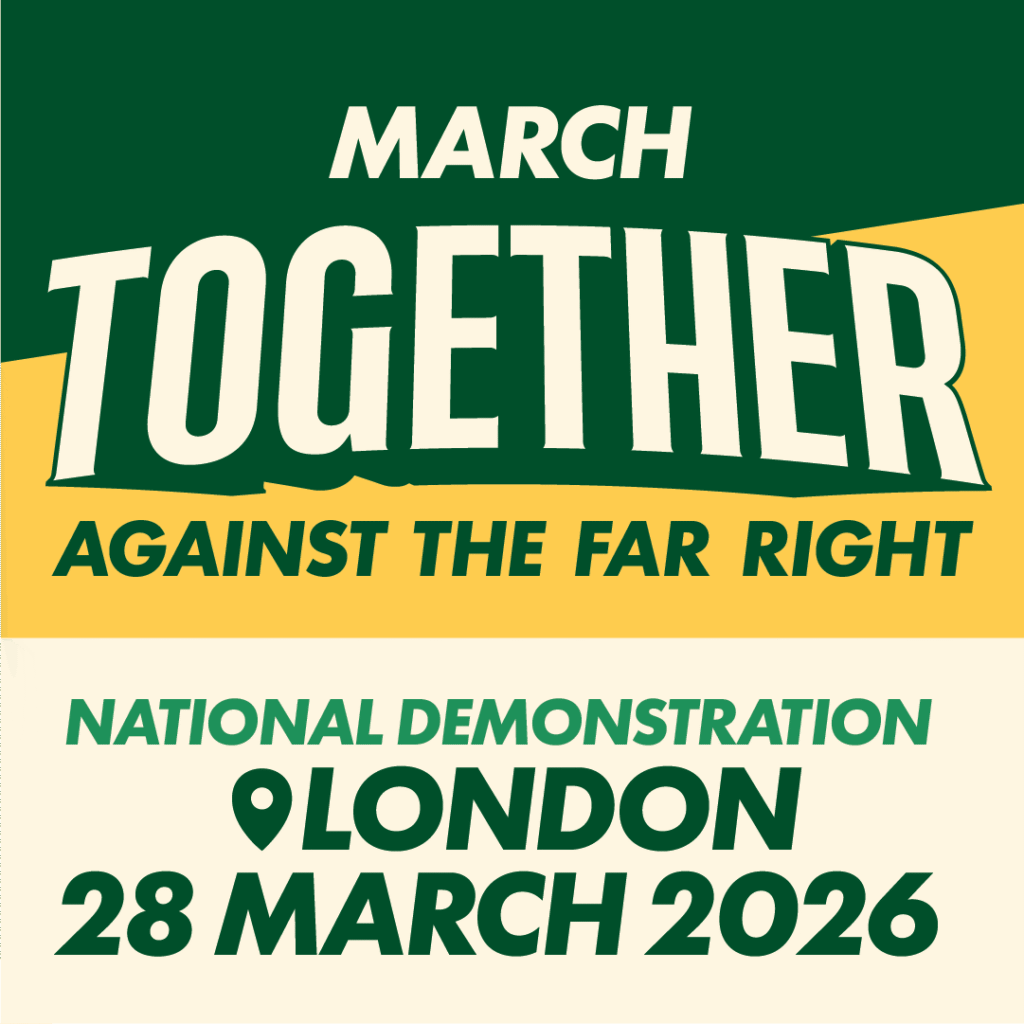

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.