The EU referendum: Four arguments for ‘yes’ and a proposal

We must distinguish a workers’ case for keeping EU membership from the business one that the Labour leadership will almost certainly promote, writes Luke Cooper

The EU referendum will be a major debating point across the Labour and working class movement. It will blur many of the divisions that we have become accustomed to, with both the radical and centre-left very likely to split into opposing camps.

Like on so many other questions, however, there is little sign of such a debate within the dreadfully uninspiring leadership election itself. Each of the Labour leadership hopefuls appear to be intent on moving the party further to the right in economic and social policy, and all support a campaign for a ‘yes’ vote (the referendum question will be a variant of: ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?’). It is already possible to predict that the Labour leadership will closely align their arguments with those of the Tories, making a ‘business case for Europe’, which will largely consist of instilling fear in the apocalyptic economic affects of a ‘Brexit’.

There are already echoes of the mistakes Labour made with the Better Together campaign in Scotland in taking this stance. By uniting with the Tories they succeeded in turning the party’s longer-term malaise north of the border into a full-scale crisis, one that reached its crescendo with the landslide victory of the Scottish Nationalists in the general election. While Liz Kendall allegedly favours a ‘distinct and distinctive’ independent Labour campaign for a yes, it is hard to imagine how this would be politically different from a broader, big business-backed alliance given that she has positioned herself as the candidate of choice for the Blairite wing of the party.

David Cameron’s much-lauded ‘renegotiation’ is very unlikely to amount to anything more than cosmetic changes in Britain’s relationship with the EU. Although it will entail new, ‘nasty party’-style attacks on the rights of EU migrants in Britain not all these measures require treaty change – as Tory eurosceptics have pointed out. This strongly suggests he has already decided to campaign for a yes vote come what may. Meanwhile, for UKIP and the right of the Tory party (both inside and outside of parliament) British exit will be treated, at least in part, as a referendum on the free movement of people and associated anti-discriminatory labour laws in the EU.

What should the left make of this situation? And what vote should we advocate?

Some on the left and in the labour movement will argue for a ‘no’ vote based on the simple, and in itself correct, point that the EU institutions have been key to imposing neoliberalism and austerity across Europe. Kelvin Hopkins has already put this ‘purely economic’ case on the Radical Labour site. Others are unfortunately likely to use it to challenge the principle of the free movement of people within the EU.

I want to propose that the left needs a broad based campaign, bringing together trade unions, migrant rights’ organisations, community groups, the Green Party, Labour Left, and a wide range of others movements and activists – which combines a call for a yes vote with a critique of all that is wrong with the EU. The latter should include a sharp attack on the lack of democracy in European institutions, their role in imposing neoliberal austerity on the peoples of Europe, and the proposed TTIP agreement. Such a campaign could unite together a section of the left within the Labour Party with those, like myself, who are outside, in an anti-austerity and internationalist movement.

Here are four reasons why I believe this is the only progressive option for socialists.

-

We should support the principle of ‘freedom of movement’ within the EU

Anti-immigrant rhetoric – encapsulated by, but far from limited to, the rise of UKIP – has become feverish in recent years. While such views have been a persistent feature of British social attitudes for some time, since the turn of the century there has been a clear increase in the number of people considering immigration to be an important political issue when it comes to voting. One study has shown, for example, that in December 1999, as few as 5 per cent of people considered ‘immigration and race relations’ to be in their ‘most important’ political issues. But this grew in the 2000s, rising to a peak of 46 per cent in 2007 and remaining high in more recent years too.

The big change we’ve seen in this period is precisely the focus on European migration to Britain, rather than from former colonial possessions. This sentiment has driven the rise of UKIP whose xenophobia, nationalism and ‘little Englander’ opposition to ‘political correctness’ has resonated with the wider cultural shift in the public mood. Indeed, it is arguably the case that we wouldn’t be having a referendum on being in the EU if it were not for this growth in the myth that migration – and not the corrupt rich and powerful elite at the top – is responsible for the problems of working people.

These arguments tend to be focused on the perceived affects of immigration on jobs and pay. But most studies – such as the one co-produced by Class and Red Pepper – have shown that these are largely just that: perceptions, and not realities. Migrants tend to be young, tend to contribute more in tax than they use in services and welfare, and give a boost to consumer demand. The British economy might not even have moved into recovery in recent years if it had not been for the resumption of annual increases in net migration levels.

But regardless of the economic effects, there is a principle at stake here. All EU workers, including the British, enjoy the reciprocal benefits of the principle of freedom of movement enshrined in the Treaty of Rome. There are 2 million British people who have moved to other EU countries, with over half of them residing in Spain alone. Of course, British people like to see themselves as different – as “expats”, not immigrants – but this sadly reflects an enduring colonial mindset. It is a way of thinking that denies logic, seeing no contradiction between having one rule for Brits in the Algarve or Costa del Sol, etc., and another one for migrants living here.

As internationalists who believe that ‘an injury to one, is an injury to all’, regardless of nationality, ethnicity, gender, disability, and so on, we have to fight to defend the benefits the principle of free movement offers all EU workers. It ensures that all of us can move to other member state countries, live, work and settle there, bring our families, and not be discriminated against in the labour market when we do so.

-

There are no national solutions to austerity – we need an ‘alternative globalisation’ to tackle the huge challenges of the 21st century

There can be no doubt that the Eurozone is broken and that Southern European economies have had to pay an extraordinary price for membership of the single currency area. The long drawn out negotiations over the Greek crisis, and the outrageous refusal of Germany and the Troika to countenance any concession to Syriza’s manifesto, is pushing the country towards a Grexit. While this would involve huge difficulties, it would allow Syriza to move away from austerity economics.

Britain is not, however, Greece and we will not be voting on Eurozone membership in the forthcoming referendum. In Greece too, the debate is about the Eurozone, and not EU membership as such. Any comparisons between the situation faced by Greece and Britain are necessarily crude and misleading. Austerity, after all, has not been imposed on Britain from the EU or elsewhere. It is being driven forward by our own elites, who were also central to exporting it to mainland Europe in the first place.

In a globalised age there are clear limits to what a national economy with even the most radical and progressive government committed to ending austerity can achieve. Economic development has substantially outgrown nation-states, creating huge challenges for the left in how we confront a global capitalism that recognises few borders. As the scale of capitalist development, and its global reach, has expanded so too has its power. This means, amongst other things, that it would take joint action by multiple governments across Europe to pioneer an alternative to neoliberal globalisation based on the spirit of solidarity, collectivism and economic democracy.

If social justice requires a transformative change that reaches across borders, so too does an ecologically sustainable economy. The urgent need for common global action to cut CO2 emissions is only the first of a series of environmental challenges. This also clearly requires substantial and lasting cooperation across the borders of Europe.

This does not mean the EU is a benign or neutral arbiter on these issues – it has been largely colonised by neoliberalism and interests hostile to the transformative change Europe needs. But an alternative based on national autarchy is neither possible, nor desirable.

In Britain, the political right have aggressively promoted the idea that the EU is a super-state that leverages power undemocratically over national governments. However, a closer look at the workings of the EU reveals a much more complicated picture than this would assume. Far from resembling a ‘super-state’, the EU has created a system of horse-trading between member countries existing alongside a series of undemocratic bureaucracies. A lack of substantive democratic control over its executive functions privileges the most powerful states, particularly Germany, as we have seen during the financial crisis, and the central bureaucracies committed to the forward march of neoliberal globalisation.

The fight against this elite must be internationalist and pan-European, asserting the will of the peoples of Europe for democratic change – and crucially cut against the trend to turn inwards into national isolation. Leaving the EU institutions, undemocratic as they are, will not help us fight the financial and political kleptocracy that is strangling the peoples of Europe. To defeat them we must campaign with our international allies for an alternative ‘democratic and citizen-driven Europe’.

-

We must organise, as the left and social movements across Europe, for an alternative Europe based on mutual solidarity and democracy

Syriza underlines both the challenges and possibilities for the movements of the radical left, inside and outside parliament, across Europe. Its rise to power was unprecedented, signalling the emergence of a moment in which the socialist left suddenly finds itself in a position where power becomes a living possibility.

Owing, however, to the very novelty of its rise, Syriza, has found no allies amongst other European governments. They have confronted a continent still dominated by conservative, right-wing forces favouring a deepening of austerity on principle, or social democratic parties that are not prepared to countenance any concessions which might appear to reward the radicalism of a party to the left of their political tradition.

This poses two linked tasks to the radical left, whether parties of the European left or socialists within the centre-left parties, and the social movements. Firstly, we must redouble our efforts to win the arguments against austerity in our own countries, combining this with a clear stance against the scapegoating of migrants, and all marginalised and insecure groups, for the costs of the capitalist crisis. Only with ‘more Syrizas’, i.e. more governments of the radical left, can we hope to create the foundation for a lasting and radical alternative to neoliberalism and austerity.

Secondly, we must increase all avenues for our practical cooperation as an international movement. A critical immediate task we face is to build pan-European solidarity with the Greek people against the Troika, supporting the call for demonstrations and mobilisations across Europe from the 20th to the 26th June. Cooperation ‘within the institutions’, such as the European parliament, will need to go alongside our explicitly internationalist popular mobilisations on the streets.

-

Outside of the EU Britain will move even further to the right

Lastly, we must understand the situation that we are living and fighting in, and how it shapes the likely consequences of the policies we advocate. A victory for ‘no’ in the referendum will provide UKIP with a huge boost to its political prestige. This is particularly the case if, as seems likely, it is a victory won against the majority of the parliamentary Conservative party, and the combined weight of the rest of the political spectrum (from Labour, to Liberals, the Greens, etc.). There is no reason to believe that this political context would be amenable to advancing the demands of the left – and plenty of reasons to think it would encourage yet another lurch to the right.

Whether in the Conservative Party or UKIP most supporters of Brexit are overwhelmingly hardline Thatcherites. This would be their victory, not ours. They would support signing a free trade agreement with the EU, guaranteeing freedom of capital to move across borders, but not people, and would continue to back TTIP.

On the other hand, the reverse is also true. A yes vote – the larger the better – would be a significant defeat for UKIP and the hard right of the Conservative Party. It would keep our borders open to European migrants and be a victory for the anti-racist cause. Socialists in the UK would still be engaged in the fight to transform and refound Europe, and could be proud to be part of growing, radical international movement.

That’s why a yes vote is the only progressive option for the left.

Luke Cooper is a writer, activist and co-author of Beyond Capitalism? He lectures in politics at Anglia Ruskin University and his twitter handle is @lukecooper100. This article first appeared on the Radical Labour website.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

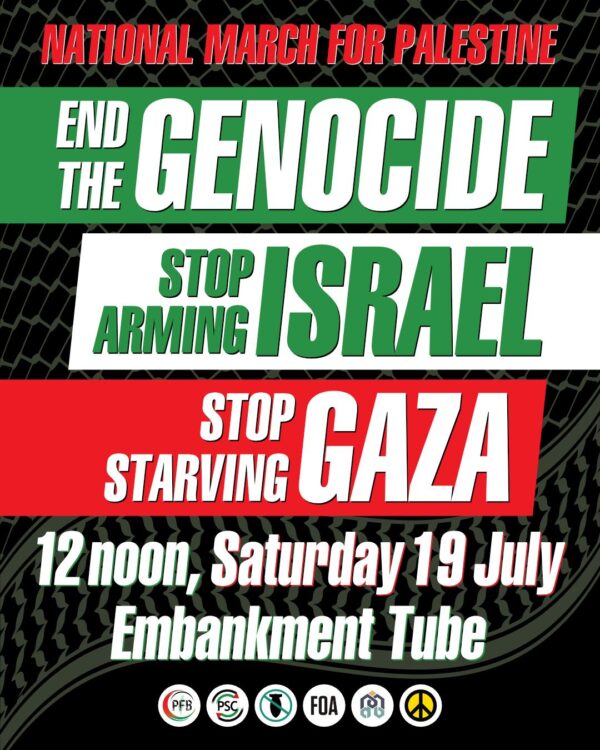

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.