The 1913 Dublin Lock-Out: a hundred years on

Keith Flett writes on the Dublin Lock-Out. He will be introducing a London conference on the Lock-Out which takes place at the Institute of Historical Research at midday on the 2nd March. Speakers include John Newsinger, Terry McCarthy, Terry Ward. Admission free

The Dublin Lock-Out which started in August 1913 and ended in January 1914 was one of the biggest labour disputes of the last century in the British Isles. Probably the only other comparable event was the British miners strike of 1984/5. Both provoked special discussion by the British TUC such was their widespread impact and importance.

Why however should it be something that interests anyone but labour historians today?

The basic facts of the dispute were that transport workers were faced with being locked out by a vicious anti-union employer William Murphy if they did not leave the Union. Faced with this the union’s leader Jim Larkin called them out and hit initially the Dublin tram network.

The battle over union recognition was a bitter one, where Murphy was able to get most other large Dublin employers to back his union busting stance.

At its Manchester Congress the TUC offered support- despite reservations of the General Council- and the solidarity efforts of mainland workers kept the dispute going until January. It was undermined by the widespread use of scabbing and ended in defeat.

An epic battle certainly but also one that raised many wider issues relevant to anyone active in the labour movement today.

Prior to the lock-out Larkin had been pursuing an often successful strategy of organising workers and running disputes to raise their often very low wages and improve conditions. In fact Larkin had been so successful at this that levels of union membership were often higher than on the then mainland.

It was this that employers were determined to smash and in doing so they were able to call on the full force of the State. Police violence towards strikers was a feature of the dispute as it had been across the years of The Great Unrest from 1911 onwards in places such as South Wales and Liverpool.

A slightly different register was at work in Dublin however because to add to the class struggle there was also the national question and the role of the British Government. The complications can be glimpsed when it is understood that the union buster Murphy was a nationalist politician.

A street defence force was used to protect strikers from State violence that became by the time of the 1916 Rising the Irish Citizen Army. James Connolly had been one of the leaders of the 1913 strike.

The defeat of the strikers and the success of the lock-out strengthened the employers and in a wider frame can be seen to reflect some of the post war tactics used by British bosses in the 1920s including the General Strike. It also had many characteristics in common with US labour disputes of the period reflecting an internationalisation of employers and union strategies that is still with us but often less obviously discussed.

The defeat of the strikers and the success of the lock-out strengthened the employers and in a wider frame can be seen to reflect some of the post war tactics used by British bosses in the 1920s including the General Strike. It also had many characteristics in common with US labour disputes of the period reflecting an internationalisation of employers and union strategies that is still with us but often less obviously discussed.

Counter-factual history often amounts to little more than historical entertainment but the fact that Larkin was not able to continue his previously successful strategy of unionising Dublin workers and improving their conditions can’t have done anything but raise other perspectives in the minds of some- particularly the issue of British rule. Certainly when the TUC declined to try and stop goods from the Dublin docks moving in the mainland in January 1914, there was a tendency to blame the ‘British’ although it had been the solidarity of British workers that had allowed the dispute to continue for as long as it did.

Other longer term consequences of those months in 1913 included the formation of the Irish Labour Party and a permanent transport union structure which, along with Larkin, became a central feature of life in the 26 Counties after independence. So to view the Lock-Out simply in terms of a defeat that led nowhere is to avoid the point that defeats have legacies as much as victories do.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

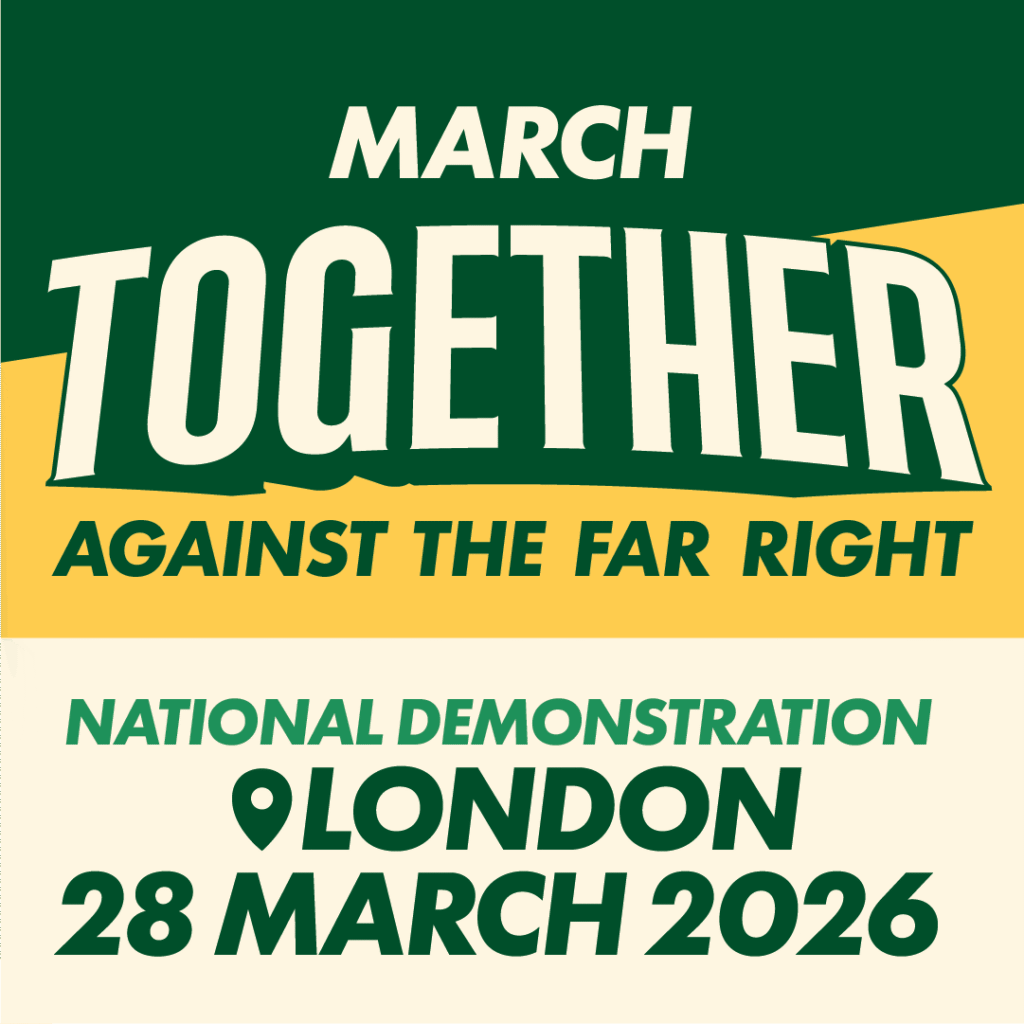

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.