Take democracy back!

But re-define it first, writes John Tummon – and give only guarded and limited support to the campaign for STV

I must admit I am a reluctant participant in electoral work and regard it as a subsidiary activity, at best, to be considered tactically and never as a strategy; I have worried about the electoralism that seemed implicit in Left Unity at its inception, but joined because it was not yet clearly the point of the party. That is still the case but if it does become formally regarded as the most important activity of the organisation, I will leave LU at that point. I hope this article explains why I feel so strongly and am somewhat alarmed that my branch has invited a speaker from ‘Unlock Democracy’ to tell us about the importance of campaigning for STV (the single transferable vote).

While STV would be progressively ‘democratic’, in the same marginal way that compulsory trade union ballots are hailed as more ‘democratic’ after being tampered with by successive Tory and Labour governments, this kind of thing is, I hope to show, no more than shifting the deckchairs around. The main reason is that the internal networking of the oligarchy – both the international oligarchy and its British branch – is almost entirely outside the formal political processes STV hopes to amend.

Also, this is a strange time to be raising STV – 2 years after the mainstream debate. The chances of it getting anywhere near adoption are zilch, whereas the chances of building a strong movement of the unemployed, for instance, are better than they have been for decades.

Making a call for STV a major campaigning initiative would be to privilege electoralism as not only a strategy, but as THE strategy for taking LU forward.

However, I also believe that there has not been a better opportunity in several decades for the Left to make a bid to take over the mantle of democracy from the neoliberals, who have abused it as their false flag in waging the Bush-Blair war on terror. However, first, a little potted history:

1. The Left has a poor record in defining and promoting democracy as a key aspect of working class advance. The best thing I have read on this is here.

2. The Tories mounted an unending ideological attack on trade unions from the 1960s onwards based on the contradictions between trade union and working class political practices and the norms of representative democracy. This featured the ‘union barons’ mantra, the attack on the Labour Party’s bloc voting system for its TU affiliates and the alleged intimidation of the mass of trade union workers by militants, though the use of mass meetings to decide strikes rather than the secret ballot. Tory anti-trade union legislation in the 1980s came on the back of this long campaign that benefitted greatly from the Cold War background to it; a Cold War which saw so many examples of ‘democracy’ being used as a flag and symbol to distinguish ‘us’ from the Eastern Bloc societies.

3. In these ways, the right has, until now, monopolised and defined the democracy agenda and succeeded to such an extent that most people have come to understand that the political-economic system we live in is ‘democracy’, not ‘capitalism’. This has been a big ideological hurdle for the Left for many decades and the reason why we need to campaign to change this.

4. Since the credit crunch, however, representative democracy has experienced a significant unravelling of its credibility. This is not just about its various scandals, MPs’ noses in the public trough, the Cabinet of Millionaires or the familiar issues which make the headlines, but the rise of the Downing Street machine as an alternative to the civil service, with its finger in so many pies and its doors so open to the rich and powerful to influence policy and its implementation. The televising of PMQs every Wednesday and the regular snippets on TV news have not showcased what was hoped for, but instead exposed a bunch of sound-bite poseurs and their playground antics. Voter turnout is in long-term decline and the medieval imagery of Parliament has become symbolic of its seeming irrelevance to many among the younger generation, who show the highest rates of voter disinterest.

5. Representative democracy is still very new and only recently stabilised. From 1660, once monarchy was brought back, England and then Britain developed a system of government based on a narrow oligarchy of landowners, capitalists and bankers allied with the Crown, with strict property qualifications put in place to prevent the vast majority of people from being able to stand for parliament or even vote. For two centuries, until the 1867 Electoral Reform Act, this system functioned as the way the various sections of the ruling oligarchy negotiated the differences between them, so that by the time that the Labour Party started to get its candidates elected in the early 20th century, it was already set in stone – its rules, structures, networks and culture were too strong for a handful of Labour Party members to make an impact; instead, they mostly got sucked into its quaint ways of operating and came to share much the same political perspectives as the Tories and Liberals.

Unelected members of the oligarchy like senior civil servants, military commanders, judges and the Corporation of the City of London remained, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, in regular touch with government ministers, usually in the private clubs they both spent lots of time in. With some exceptions, like the Attlee government straight after the Second World War, the Labour Party, however many votes it got in elections, was no match for the power of this oligarchy.

Nowadays, the private clubs have mostly been replaced by the thousands of corporate lobbying groups buying time with ministers at invitation-only meetings, where they are able to exert incredible influence on government policy and its implementation. Governments make it their priority to get as close to media editors and owners as they can, as Leveson showed, and these media people are themselves powerful figures within the oligarchy.

The British political system is still a means of the rich and powerful negotiating their differences – that’s what it is for and, since the mass media grew in size and influence, it is also a way of talking at the people, presenting the oligarchy’s views and decisions to the people. That is why there are strict rules on which parties can have a Party Political Broadcast; it is why political parties are privately funded.

That is why I am an electoral sceptic and think the idea of the Left getting behind STV is the very opposite of LU’s policy that Left Unity has no interests separate from the working class. All that can be claimed for STV is that it would make it easier for left groups to get a couple of MPs; it would not move working class struggle to any improved prospects nor the decision-making of the state any closer to representing the interests of the working class. A couple of Left Unity members would become MPs, enter parliament, absorb its culture and become useless to the working class, that’s all.

I think much of the Left has steered clear so far of launching a campaign to reclaim democracy because it is still stuck in economic reductionism (a tendency to reduce all politics to material and economic motives and causes); my view, on the contrary, is that Gramsci’s analysis of hegemony is essential to a full understanding of why continued exploitation and oppression does not cause rebellion. Without naming names, I find it ironic that the same variants of Left thinking that are most reductionist are also those who habitually indulge in electoralism. Without ever putting forward their own theory of electoralism, these political tendencies, by implication, therefore agree with the classic social democratic, left reformist reasoning for being an electoral party. As I’ve already stated, I think electoralism, in its Left Reformist incarnation, was fundamentally flawed – the tragedy of left reformism is due mainly to its expectation that achieving formal control of the House of Commons could ever produce executive decisions that reflected a democratic mandate from the voters and the demand for STV repeats that mistaken analysis.

What prevents executive decisions of government achieving this kind of sovereignty within the state are the multifarious ways in which the constituent parts of the oligarchy come together to develop their own consensus on major issues and strategic decisions and the immensely powerful levers of state and of civil society which they have at their disposal, completely independently of MPs. I use the term oligarchy rather than ‘ruling class’ because ‘ruling class’ is used in two quite different ways and is therefore ambiguous – (1) it refers in general terms to the social class of a given society that decides upon and sets that society’s political policy, but Marxists also use it to mean (2) those who own and control the means of producing wealth and thus are able to dominate and exploit the working class, getting them to labour enough to produce surplus value, the basis for profits, interest, and rent. This mixes up two groups of people who are essentially, allies; the parts of the social surplus that go to the actual capitalists and major shareholders also supports a wider group – the oligarchy, the vast majority of whom are able to live entirely or mostly off interest and carry out various non-productive but politically and socially crucial functions in support of oligarchical domination, including joining the professional political class. That’s why I prefer the more inclusive term ‘oligarchy’ – because it provides a broader and more complete picture of what we are up against and who is up against us. The entire British and French empires were built and administered in precisely this way by the oligarchy (almost all colonial district officers came from one Oxford College – Balliol), so was the network of tax havens (based on Crown Dependencies) and the institutions of global capitalism such as the IMF, World Bank, GATT, the Bank of International Settlement and Central Banks; none of these was founded or grew or was sustained as a result of formal political decisions. Under capitalism, the economic realm, including the media, the monarchy, the judiciary and the church, has a firewall protecting it from formal democratic decision-making, irrespective of the electoral system used in any one state. Politicians (all career professionals nowadays) have no choice but to bow to the consensus achieved undemocratically by the oligarchy or find they are fatally undermined – for instance, the oligarchy had already moved towards supporting a welfare state in order to get out of the Depression before Attlee came to ‘power’ and made it happen! If he had moved independently from an oligarchical consensus (of which he was, anyway, a part), Attlee would have been fatally undermined, as Harold Wilson was. That’s why the Tories in the 1950s actually built far more council houses than Labour managed – because the oligarchy recognised this was necessary for social peace and to build consumer capitalism.

We should have no illusions in STV – all it can do is put British voting in the same formal position as in Europe, which would be only a slight improvement. If we sowed illusions in what else it could do, we would be doing the working class a disservice.

As for the industrial democracy practiced by the Russian and German soviets in 1917-1919, on its own, this would default to producers always calling the tune over the common good unless consumers and communities had their say on what is produced and how hard-wired into the rules of socialism. What I believe in is participatory grassroots democracy – popular meetings at neighbourhood level upwards, backed by carefully-controlled internet-based voting and decision-making processes. Nothing need be decided in the age of the web by ‘tribunes’ of the people in a legislature or National Assembly – it can all be done by the mass of people online, with executive implementation of decisions through an administrative cadre based on strict rotation, so we have neither a permanent political class nor a permanent bureaucracy. The communications revolution means there is no longer any excuse for ‘representative’ politicking!

If the Left is finally going to try to take democracy back, it won’t achieve this through a campaign on STV, but by re-defining democracy and arguing that participatory grassroots democracy and the use of the internet for making decisions is closer both to the spirit of the ancient Greeks (and to the open decision-making strike meetings of workers until the Tory anti-union laws) and to Abraham Lincoln’s famous dictum that democracy is the government of the people, by the people, for the people.

5 comments

5 responses to “Take democracy back!”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

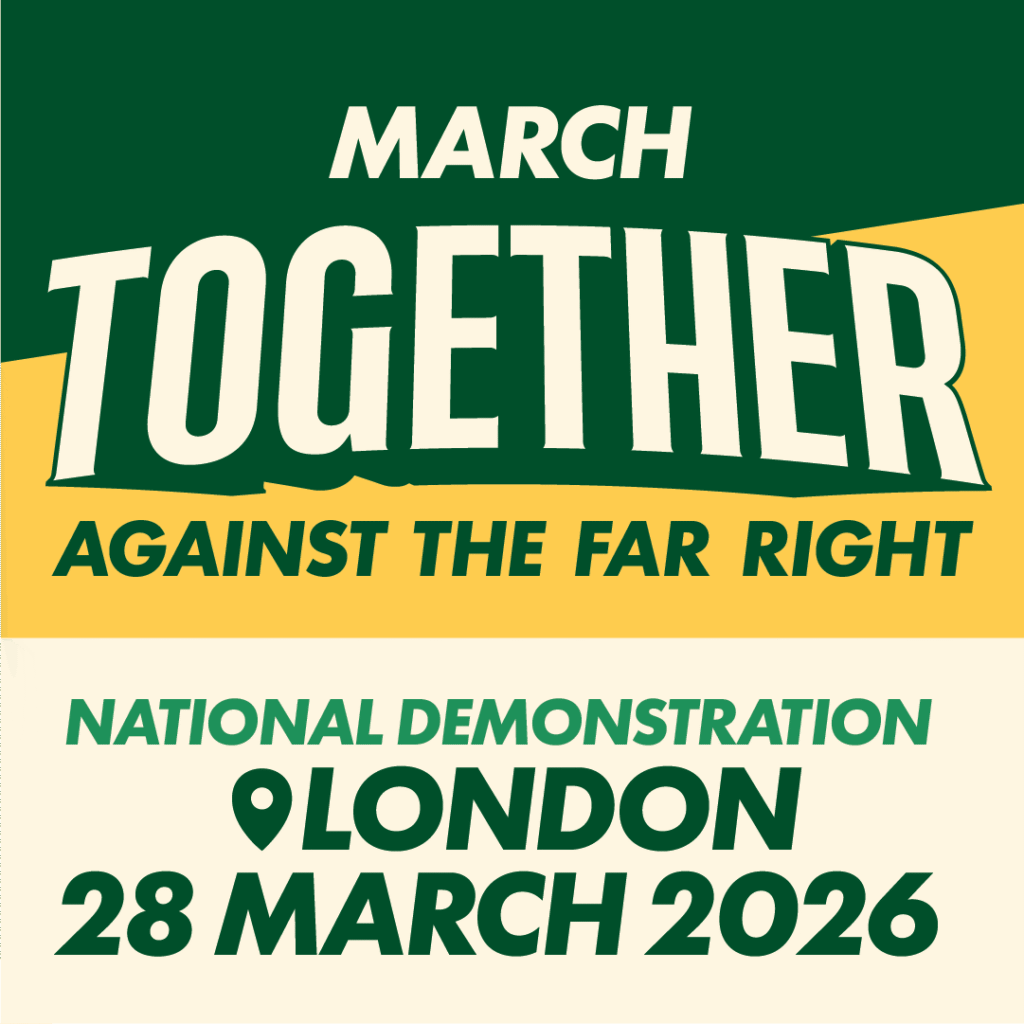

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

I am surprised at John, our Stockport Left Unity Branch Secretary, stating in this public forum, that he is, I quote, “somewhat alarmed that my branch has invited a speaker from ‘Unlock Democracy’ to tell us about the importance of campaigning for STV (the single transferable vote)”.

We normally plan our discussion meetings some months ahead and a list of forthcoming topics appears as a standing item on the agendas of our monthly branch business meetings. John has not on any previous occasion expressed his alarm at our decision to invite a speaker from Unlock Democracy to discuss STV with us, either in response to the circulation for review of successive monthly draft agendas, or at any of our meetings.

Moreover John is talking about a branch discussion meeting. We have not yet either received or discussed a motion proposing that the branch raises the question of STV within Left Unity’s democratic policy making process, so there is plenty of time yet for John to seek to sway his branch’s view.

Hence, the proper place to discuss John’s newly articulated alarm at a democratic decision of his branch comrades on what they want to discuss and on what that desire to discuss might lead to, is within the branch.

I’ll be happy to champion a proposal that Left Unity throws its weight behind a campaign for STV when it becomes my branch’s policy that this should be so.

The last thing I would say here, at this point in time, is that, as we know, John is an outspoken supporter of Left Unity’s Republican Socialist Platform. It would be helpful for us to learn whether John’s disdain for progressive reform of the voting system and his counterposition of “down with representative democracy”, reflects the LURSP’s politics, or whether John is promoting a personal viewpoint only.

John, I assumed (wrongly) that the branch would be voting on this in my absence, hence my emails to you and others in advance of the meeting I was going to miss. As you have since informed me, this is now in the future.

Yes, the proper place would have been in the branch, but I gave advanced warning that I would have to miss the meeting concerned. I am replying to you publicly now because you have chosen to criticise my conduct in this public forum, alleging, by implication, that I am circumventing local democratic decision-making.

However, this article posted here is not just about or even mainly about stv, if you read it – it is fundamentally about what it says on the tin – the need to take democracy back by re-defining it and distinguishing it from representative democracy, of which stv is a more porgressive version.

You have promised to respond to my substantive argument on why I see it this way, but your posting above is not a counter-argument on this at all; just an airing of your feigned surprise about my alarm, which you already knew about, so it is not ‘newly-articulated’ at all, except to those who are not in our branch and did not get my previous emails on this.

As a self-declared believer in playing the ball not the man, I am surprised that you have chosen this form of response, which skirts around & personalises the main issue that separates us – do we or don’t we need to re-define democracy in a way quite different from representative democracy. This is a view I have held for some considerable time and was central to the 2 articles I put on the LU website Discussion Section several months ago about what socialism means. Grassroots democracy is fundamental to what being a Libertarian Socialist means and I thought you were well aware that this was central to my politics.

I don’t think you need to know first whether or not my views on this are shared by the RST within LU in order to mount your counter-argument; surely you can do that anyway?

We both go back a long way in our work together so it should be a simple matter to draw a line under this and focus on the substantive issue – the reasons why we take very different positions on the issue of democracy and how, if at all possible, these can be reconciled within a single LU policy. I look forward to seeing what you have to say on this.

I don’t think we have ever seen, in Marxism, a coherent theory of democracy. Marx and Engels themselves were keen students of what Bakunin and Proudhon said about democracy and were highly critical of the so-called democracies that were coming into being in various capitalist countries, precisely because they were fierce advocates of genuine grassroots democracy, as evidenced in the Paris Commune and Marx’s belief that it showed the way forward to the political forms socialism could take.

Crucially, despite the breach with anarchism during the First International, there was agreement between anarchists and socialists in favour of direct, not representative, democracy.

After this, though, came the period in which social democratic parties like the SPD and Labour Party started to take part in elections under what became known as the representative democratic form and Lenin took his party into the Tsar’s Duma; Trotsky then joined Lenin in assuming representative democracy was a viable vehicle for a vanguard party to use to establish its leadership of the working class and then to take state power. The problem is, neither Lenin nor Trotsky theorised this at all, so there is no non-social democratic theory of representative democracy or of why socialists should participate in elections under representative democratic forms.

Trotskyists believe that in a modern social context it is necessary to have many parties, an open press, and so on; in other words, they buy into the notion that representative democracy is a political system, as opposed to a variation of bourgeois oligarchical rule, and a vital stepping stone towards the establishment of socialism via the takeover of the state. But, once socialism is achieved, it is not clear whether Trotskyists want to retain pre-revolutionary representative democratic forms or use direct democracy, based on workers’ councils.

Both Trotskyists and anarchists point to classic examples of Workers Councils such as the Spanish Revolution and the Portuguese Revolution in 1973-74. Workers’ councils arose in the early 20th century among machinists; ironically, these workers’ councils arose out of the needs of capitalists to organise war production. Nevertheless, those workers took over the means of production and the running of the factories and organised their own council. Those workers became the epicentre of the revolutionary movements in the period before and after the First World War but never won power anywhere; in Russia they were squashed by party rule and in Germany the SPD used the right wing paramilitaries to crush them and set up a representative democratic state instead.

Contrast this with anarchism after the split with Marx, which continued to develop its theory on democracy; anarchists are for federations of self-managed groups. This means that the membership of such organisations decide policy directly at open meetings. Anyone delegated from that group to do specified tasks or to attend a federal meeting are given a strict and binding mandate. Failure to implement that agreed mandate means that the delegate is instantly replaced. In this way power remains in the hands of all and decisions flow from the bottom up. Anyone placed into a position of responsibility is held accountable to the membership and any attempt to usurp power from the grassroots is stopped.

Anarchists have long argued that we should organise in ways that prefigure the kind of society we want and that only freedom can be the school for freedom, that we only become capable of managing society if we make our own decisions and directly manage our own struggles and organisations today. It seems strange to anarchists that self-proclaimed socialists, such as Trotskyists, should be seeking to reproduce one of the principles of capitalist politics into anti-capitalist movements.

Libertarian socialists accept the anarchist theory of democracy because it makes sense strategically to be able to be able to a) describe and show the working class what socialism will mean and b) there is no other theory of democracy in the rest of the Left; it is just a case of following the social democratic strategy without saying why. In Trotskyism, by contrast, there is a disconnect between how we are supposed to organise now and how we propose running socialism; its all ‘jam tomorrow’.

That is why Trotskyists will not debate the issue of Left wing involvement in elections; it is seen as self-evidently the right thing to do, with no theory whatsoever behind it.

A broad Left-wing party like Left Unity that wants to be different should have no fears about taking ideas and policies from other strands within the Left, including anarchism.

John Tummon

I agree with taking part in parliamentary elections because

a) the vast majority of people in advanced western democracies focus their ideas of political debate and controversy on electoral politics. Not to engage in that field of activity leaves it open to others to push their views in our absence. If we are not in the debate, we can’t win people to our views, and will be marginalised.

b) To proclaim, at this moment, with the current consciousness of most people, that parliamentary democracy should be abandoned in favour of workers’ councils or anarchist self-organisation groups would make us look utterly absurd.

c) more controversially, I am not sure that the kind of self organisation you advocate, with everything decided at mass meetings, is, in any case, necessarily desirable. I think it very likely that within a short period of time these council bodies would become dictatorships of those people who are i) articulate and intelligent ii) full of themselves iii) obsessed with the detailed organisational points that bore the pants of everyone else iv)incapable of developing other, more rounded, interests or relationships v) free of responsibility for other dependents such as children or parents and vi) not disabled. I feel that a representative form of democracy with elections at regular (very regular and short) intervals actually better protects the interests of the majority. Why is it good that our policy was made by people who were willing and able to travel to London or Manchester, rather than delegates mandated by local groups where everybody could discuss the issues?

d) I believe the actual form of rule of the majority of people will almost certainly take a form that none of us can predict at this stage. There has never been a successful revolutionary movement in any country like those in the advanced capitalist world today. Who knows what structures will be thrown up in the course of that struggle. Therefore trying to predict, let alone proscribe, the organisational structures of a post-capitalist state is rather pointless.

e) the left have a shocking record of apologising for brutal undemocratic regimes and we have to expunge that mental association by being the most resolute in fighting for every partial democratic right here and now.

Given the above points, I feel that at this stage it is vital to raise demands to make the current parliamentary system as democratic as possible : shorter gaps between elections, abolition of the Lords, control of the executive by the legislature (election of ministers etc),democratic control of the army and civil service, the power of recall, a proportionally representative electoral system, controls on lobbying and spending, limits to politicians salaries, full local democracy at every level and so on and so on.

Of course all of these together would not in themselves do anything to end the power of the elite who currently are able to run society and the state in their own interests. Indeed, they may never be achieved until after the left has taken power (and may be superseded by then anyway) but even so the campaign for them would allow us to neutralise some of the ideological obstacles that the current system puts in the way of any attempt on power by a party of the left. If any of them ARE achieved by mass campaigning, then they take one weapon away from our enemies. PR would be of enormous propaganda benefit to the left, as it was in the Scottish Assembly when a handful of socialists were elected. Equally, the current electoral system keeps the left in the prison of “best of two evils” labourism that has made it so difficult to build a left party for decades.

Thanks, Ray G, for joining in this discussion.

My response to your points in turn:

a) You say that not doing electioneering “leaves it open to others to push their views in our absence”. As I have posted before on here, forget the General Election – the media decide who is credible and the public then get swamped with the parties they, the media, choose; UKIP had no seats and were nothing until the media started to talk endlessly about them; the BBC even highlighted an increase in Rumanian immigration at 6 pm on voting day, before most employed people vote! In our TV era, for most people, things are only real and of significance if the media highlight them. UKIP therefore became a realistic alternative; we are not, in the media’s eyes, and therefore will not be promoted in the same way, ever. UKIP were seen as having a chance; we were not. It will always be this way for the left unless and until we painfully build up a constituency of support over years of consistent grassroots activity; no shortcuts exist for us like they do for the populist right.

Who are these others you think are capable of penetrating the mainstream media’s narrow definition of who it will include in public debate? Apart from the odd Green face on Question Time and, of course, UKIP? TUSC? Respect? The SWP? Where is the basis for this contention in a) any national election results in the UK or b) in the electoral TV rules which specify you get ONE TV slot for standing 49 candidates (where is this money going to come from?).

The message we were giving out in our June EU leafleting all over the country was lost in the noise of electioneering and the media’s take on it. Our views will always be drowned out by TV politics at election time. We cannot raise socio-economic issues like austerity, wealth inequality etc in a climate in which a potent nationalism is being taken forward in heated electioneering campaigns. We are then basically saying to people – “you don’t know it, but this is what you should really be concerned about!”, wishing their nationalism away, pretending it is not there.

This is why I want our activity to focus instead on engaging people with our ideas away from election times.

b) You say not going into this ritualistic exercise in General Elections “would make us look utterly absurd”. That is just an assertion so until you produce a basis for this, there is nothing for me to argue with.

c) You argue that the hyperactive politicos who bore everyone with theory will always dominate meetings, but you are ignoring the power of peer pressure, which is the very lifeblood of popular organisation. Having had so much experience of watching these types fail when trying to talk at ‘ordinary’ people in this country, I am sure they will end up learning what the professional revolutionaries who went out to the Chiapas peasants and workers found out – once among the masses, you have to listen and learn and just get mocked, talked over or ignored if you don’t. The Chiapas story is instructive on the long-term effects of peer pressure on mouthy Lefties.

d) You say that “trying to predict, let alone proscribe, the organisational structures of a post-capitalist state is rather pointless”. Is it? When and if we get any mainstream airtime, like Salam Shaheen managed, we face a barrage of suppositions about the Left based on the Cold War, including ‘ if you don’t want another repeat of Soviet Russia, what, then, is it, that your version of socialism amounts to’ … ‘Er, um, we don’t think there is any point in saying anything beyond bringing the economy into public ownership because it depends on what people want’. Great answer that to a media schooled in grilling parties on why their policies are not set out in detail and costed!

e) Partial progress that fails to inspire people with an alternative vision becomes mundane reformism. You want to repeat the history of the Labour Party?

I do agree with you that a wholesale reform of the representative democracy would be worth raising, as a sort of transitional demand; it would be resisted by all mainstream parties and successfully, but it would enable us to raise the issue of what democracy actually means.

Finally, Ray, do please have a look at some of these links and try to explain to me why the re-definition of democracy is such a live issue among lots of people who are not on the Left:

They have had a mix of representative and direct democracy in Switzerland since 1848 – http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/1435383/How-direct-democracy-makes-Switzerland-a-better-place.html

and here is a research paper on direct democracy – http://democracy.livingreviews.org/index.php/lrd/article/viewFile/lrd-2010-1/21

and another – http://tasmaniantimes.com/images/uploads/brenner1LeDuc_Larry.pdf

and here is a thread discussing how direct democracy could operate through the internet –

http://www.ted.com/conversations/1213/why_don_t_we_use_technology_to.html

finally, a guidebook to direct democracy – http://www.paolomichelotto.it/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/guide-to-direct-democracy-2010.pdf

Why is this debate so big among people who don’t seem to be involved in the Left? I think it is because we are stuck with a perspective on representative democracy which has never been theorised, never been treated as a priority & just passed on without thought from one generation to the next, with most Lefties debating more arcane & economic matters over & over again. Meanwhile the right wing monopolises the stage, abuses the concept and faces no opposition from us about what democracy should be. You say ‘forget all this until after the Revolution’, which is a council of defeat and lack of political imagination.