Syriza: Looking to its right

Syriza has been held up as a party that should be emulated. Daniel Harvey examines the reality

Since the general election last year, Syriza, a coalition of left organisations, has been the main opposition in the Greek parliament. This achievement seems likely to be followed up by Die Linke in the German Bundestag, where it is widely expected that the main conservative and social democrat parties will unite together to form a grand coalition, as has taken place in Greece. The result in Greece was not exactly surprising, as Syriza has risen in tandem with the devastating austerity programme that has been imposed over the last two years.

The success of an anti-austerity party in a European country has fired up enthusiasm about the potential here of forming a broad party which stands to the left of mainstream social democracy, whilst eschewing ‘sectarian’ Marxist programmatic principles. This perspective has driven many in Left Unity to supporting the Left Party Platform in Left Unity. The hope is that LU, due to be formally constituted on November 30, will be able to achieve similar success.

However, Syriza is today facing a number of challenges, and the political basis upon which it stood for election in 2012 is under constant pressure. It faces calls from the outside to transform itself into a trustworthy party of government. A popular refrain in the Greek media is to urge leader Alexis Tsipras to “cut off some heads”, by which is meant Syriza’s left opposition, who are the most vocal in advocating that Syriza renounce the Greek debt entirely. Meanwhile, a senior figure in the ex-left Pasok party achieved a great deal of publicity when he cheekily urged Greeks to leave the country by the nearest exit if Syriza were ever to gain power.

Congress

On July 10-15 of this year, Syriza held its first congress, during which the leadership proposed a number of changes to the internal regime in order to formally transform it into a party.

In his opening speech, however, Tsipras mostly talked over the heads of the 3,500 delegates (each representing 10 members). He pointed entirely to the obvious failings of the Samaras government and its austerity agenda, whilst saying nothing to justify the internal reforms. They seem to be based on the desire to make the party function like a traditional bureaucratic party, with a strong central executive acting independently of the membership. To ram this through, the leadership reduced the time for debate to a minimum, announcing the congress in May and replacing much of the discussion with the sort of general speechifying you would expect at a Labour Party conference.

The transition from coalition to party was sparked by Syriza’s desire to qualify for the undemocratic 50- seat top-up awarded to the party with the largest share of the vote. Having made cosmetic changes before the last election to conform to the letter of the law, the Tsipras leadership has been pressurising its constituent groups to dissolve themselves. Most did this immediately prior to the congress, including the largest, Synaspismos, which boasts 10,000 members. Opposition, however, came from veteran socialist, Manolis Glezos, who heads the left and is renowned for his role in resisting the German occupation during World War II.

For Glezos, the threat was turning Syriza into a “party of applauders” – not an unreasonable conclusion, given the reforms. The most important of these, other than dissolving all the constituent groups, was, firstly, that the party chair would no longer be appointed by, and accountable to, the central committee, but elected by conference. Secondly, the system by which candidates from different platforms are listed on the same ballot paper for internal elections would be abolished.

The latter measure was clearly intended to be an attack on the proportional representation of opposition groups on Syriza’s leading bodies. And for those groups it would mean, in the words of one delegate, that they would appear in future as “alien outsiders” separate from the majority candidates on the main list. As it turned out, despite this measure being passed, the internal groupings less hostile to the leadership refused to be amalgamated into the main list, meaning that a total of six different lists appeared, completely nullifying the point of initiating the measure in the first place. The left opposition managed to actually increase its representation on the central committee, by gaining 5% on its previous 25% showing at the December 2012 conference.

This put the leadership on the defensive. After trying to bounce its reforms through, it was forced to make concessions, postponing the proposed dissolution of the remaining ‘parties within a party’ for a few months, and proposing that congress would have to decide each time whether to appoint the leader directly or leave it to the central committee. Tsipras justified himself being chosen on the former basis because a stronger and more presidential executive was necessary to steer the party through a difficult period.

However, the left was unable to win its four other motions aimed at nailing down the political basis for the party. At the moment the language used is very broad, and can be interpreted by both the left and right in whichever way they like. Generally though, Tsipras has been quite careful in his use of terms, tending not to talk about, say, debt cancellation outright, but more blandly about “negotiations” with “European partners”. He is attempting to tread a very thin line between rejecting austerity and, under the cover of internationalism, calling on Greece to come to a deal to stay in the euro zone and European Union. The motions pushed for by the left would have forced the party to reject the debt entirely, but instead take the national socialist route of preparing for life outside the EU through the nationalisation of the banks under popular control, to be implemented by a new left-only coalition against austerity.

Patriotic alliance

Despite Tsipras’s manoeuvring, the possibility of a Syriza government remains very remote. In order to win a majority for itself it would need, aided by the 50-seat top-up, something like 40% of the popular vote, but it is in fact slipping back behind its 2012 showing of 26%, as a section of the population has become disillusioned with Syriza’s reformist noises. A popular, but quite polarised, discussion centres on the comparison between Syriza and the early Pasok – the latter described by some young Greeks as the “Syriza of our parents”, which emerged as a radical formation after the end of military rule in 1974. Pasok’s leader, George Papandreou, insisted on calling himself a socialist, despite being offered the leadership of the liberal coalition leading out of the dictatorship.

On November 11, Syriza MPs moved a no-confidence motion against the government. The right- Eurocommunist faction, Democratic Left, which left Syriza in 2010, had formed a coalition with Pasok and New Democracy in 2012, but subsequently left it in June of this year in a row over the closure of the national broadcaster, ERT. The government won the confidence vote with a majority of just three. Ranged against it was Syriza on the one side and the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn on the other. The government is hanging by a thread, but the composition of the opposition makes the formation of a viable alternative administration unlikely, to say the least.

To form a government Syriza would either have to join with elements in Pasok that are widely seen as responsible for the economic mess the country is in, or form an alliance with the nationalist conservative Independent Greeks (ANEL). The former would mean a humiliating cave-in to Angela Merkel, while the latter would leading to ‘drachmageddon’ – the abandoning of the euro which some studies have shown could mean a paper loss of up to half in the value of the country’s wealth practically overnight. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) shows no sign of reversing its opposition to any coalition with the “opportunist” Syriza any time soon.

Incredible though it may seem, some commentators are seriously considering the possibility of a Syriza-ANEL coalition – the equivalent of Left Unity, in the very unlikely event it was to grow as large as Syriza, entering into an anti-EU coalition with the UK Independence Party in order to keep out a coalition of the Tories and Labour. For the left opposition inside Syriza that would obviously be a non-starter – although some might say it would be in line with the logic of its proposal for a separatist route outside the euro fold. But intellectual pressure on Syriza to look for a solution like this is nothing new – Costas Lapavitsas has been a prominent proponent, for example.

Even more prominent is Slavoj Žižek, who has shared numerous platforms with Alexis Tsipras – most recently at the sixth Subversive Festival in Zagreb, Croatia in May this year. Here Žižek pulled no Stalinist punches whatsoever in demanding that Tsipras look for an alliance with the “patriotic bourgeoisie”, so that he can show to the world that the radical left can “manage capitalism” even more effectively than the capitalist class left to itself. This he counterposed to the outdated programmes of the “utopian left”, which will never see the light of day.

Meanwhile, Tsipras has his left opposition to worry about. The leadership was largely unsuccessful in pacifying it this year and a far more aggressive bureaucratic approach would be needed to silence it. But that could provoke a further split, just as Syriza was trying to form a government.

5 comments

5 responses to “Syriza: Looking to its right”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

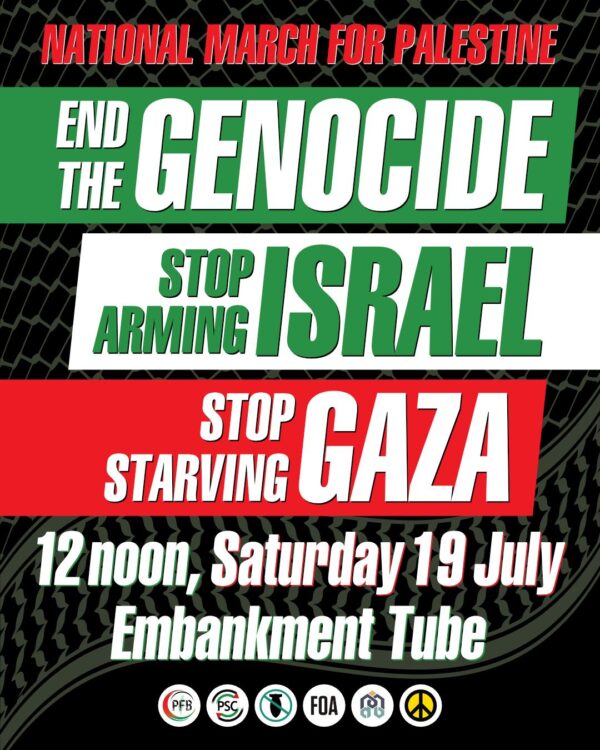

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

A sobering, and I believe, very accurate analysis of the rapid movement of Syriza from radical socialist , uncompromising, anti austerity party, to one whose ever-more power centralised leadership grouping is displaying more and more clear signs of embarking on the well trodden road of capitulation to the demands of “national salvation” (the interests of bourgeois capitalist Greece), rather than the Greek Working Class. You haven’t however spelled out what you see are the lessons for us as Left Unity here in the UK.

How does this impact on our Left Unity Project then ? many Left Unity Project supporters rightly admire Syriza for “breaking out of the ultraleft political bubble”, through amalgamating Left groups from many traditions, to achieve mass popular voting success and a mass membership – using a radical, but non-revolutionery, Left political programme emphasising pro working class opposition to the Austerity Offensive. But in fact Syriza, its component parts, and Greek politics, its deeply entrenched corrupt clientelist , party dynastic ,political culture, and history, are so radically different to the UK’s that the actual , detail, potential similarities between the Syriza rise, and its apparent imminent collapse into class collaboration, are not by any means comparable to the UK scene.

It is also the case that Syriza, as a non-revolutionary, radical Left party, is confronted with a relatively tiny Greek economy (in European and world terms) in almost total meltdown – with very little room to manoeuver. Given the lack of leverage of Greece in terms of economic and political power, and its unfortunate “privilege” in being far in advance of the rest of Europe in economic meltdown, and associated Left and Far Right political radicalisation, Syriza is actually “trapped between a rock and a hard place”.

If Syriza was capable taking governmental power and of moving Leftwards to a fundamental confrontation with domestic and international capitalism, it would most likely be overthrown by a military coup. If it, as seems more likely, moves rightwards to a series of supporter-alienating compromises with the Troika, its supporters may well shift leftwards – to the Stalinist KKE and the revolutionary Left. The outcome, for an isolated Greece, with no sign of the same required levels of working class radicalisation in other European states like Portugal and Spain or Italy or France, still looks dire even if the “radical change baton” transfers to the Greek Communist Party , the KKE (whose politics are seriously Third Period Stalinist weird), and the Far Left. A military coup after a period of economic sabotage and Golden Dawn orchestrated street fighting unrest, still being the likely outcome. I’m afraid Greece and its working class are probably beyond rescue – the future looks grim for them – and Syriza’s leadership’s shambolic manoeuverings rightwards are just one sign of its hopeless political position so far ahead of the rest of the European crisis.

In the UK context , with a massively bigger, healthier economy, there is currently much more room to manoeuver for the Left. there is no chance at present of building a political party on a revolutionary platform – but a definite growing gap on the radical reformist Left – as New Labour mimics ever more closely in its neoliberalist politics the entire policy bundle of the other capitalist parties. So , suppose we build a large radical Left , reformist socialist, party – on a programme of radical transformation of the UK economy to manufacturing from banking and services, jobs creation, restoring the Welfare state, opposing Austerity, taxing the rich and corporations, etc, etc. The political and economic power of the UK, and the strength of the UK economy is hugely greater than Greece – so we have much more time and political space to operate as a radical reformist party than Syriza. The wealth of the UK economy also provides the potential for a radical but reformist Left Party to wring significant concessions, like Welfare services protection, out of the capitalist class to a degree simply impossible in Greece.

Nevertheless a Radical Left Party in the UK trying to directly (as a Left Government) or indirectly (as a major opposition movement on the streets and in Parliament) obstruct the global drive for Austerity to redirect wealth to the capitalist class, would eventually trigger Capital Flight, currency speculation sabotage, and all the other capitalist weaponry used to enforce the “logic” of the capitalist market.

At this point would a radical, but non revolutionary, Left Unity Party likely split into compromising/collaborationist versus revolutionary components ? Most likely it would. Hard to see how this would not happen. For heavens sakes it happened within even the BOLSHEVIK Party to an extent before Lenin turned up at the Finland Station and pushed for the (as it turned out, disastrous) world historic gamble of the push for state power !

The crucial point for us though is that without building a generally reformist but principled radical Left socialist party in the UK which can potentially mobilize masses of people in initially limited, defensive, struggles (like protecting the NHS), there will simply be no effective resistance to the ever greater impoverishment of the working class. Pronouncing the need to “overthrow capitalism now” is simply rhetoric thrown at a public not ready to hear the message at all. Building the mass radical reformist party and building the intensity, and therefore the radical political content, of that struggle is the only way to build the class forces potentially capable of then moving beyond reformism to transformational political action.

In Greece, the KKE (trapped in their weird deep frozen stalinist politics)and the revolutionary Left should have been INSIDE Syriza all along, to have any chance, at the critical “political fork in the road” point” Syriza is now at, of steering it firmly LEFT , rather than rightwards to compromise. Unfortunately in the dire weak economic Greek situation, even this would be unlikely to save Greece from the victory of reaction. In the UK context, however, the job of the revolutionary Left is to be embedded within Left Unity throughout its growth period on a radical reformist policy platform – keeping its politics to the fore in a constructive way, as it nevertheless proves to be the “best and most committed reformists”. Then when at the point , many years ahead yet, that the UK politico/economic crisis reaches its own “Greek-style” “fork in the road” point, the by then mass party can potentially (but obviously not guaranteed) be won to a position of pursuing a solution to the crisis Leftwards to socialism, rather than rightwards to collaboration and defeat.

Another good post JP.

In the 1970’s there was still a sizeable working class organised in various areas which had their own strength to be able to cripple the actual capitalist system. Now the working class is decimated having sufferred de-indusstrialisation and dislocation due to globalisation on a massive scale and the 40% of people that dont vote reflects this shift. Syriza ‘grew’ not because of its politics but due to peoples move away from the established parties that dominated the post Junta electoral sphere of Greece for four decades at around 80-85% of the electorate.

From the moment the Syriza leadership has repeatedly made common knowledge they will honour the foreign debts by not calling for immediate annulment and that they will remain in the EZ everyone knows what that implies in practice. Events in the end will surpass them for a 27% vote implied one took practical decisive action to fight for power which is what PASOK did in the 70’s outflanking the then KKE with more leftist slogans and when in power introducing wide ranging social democratic reforms (80’s). The irony of the situation is that no one wants to govern for they know that when they sit in the hot seat all the contradictions of collapsing capitalism will fall on their lap and unless they have a programme which will go into direct conflict with the large transnationals that rule the world via the EU-Troika-IMF they will be burnt like all before them…

the comment in the main article that syrizia may do the equivalent of left unity ukip governement removing a consertive labour one is interesting. neil clark wrote a feuture for the newstatesman some years ago calling for a left wing right wing alliance to end the war in iraq. it was based around the right agreeing to public ownership and the left agreeing to imigration resrictions. come to think of it that sounds a bit like no2eu.

The article, ‘Looking to its right’ (November 21), is welcome, but I think for different reasons.

The general idea of transitioning from a coalition to a party-movement, considering affiliated solidarity networks, should be seen as a good thing. The organisational problem of Syriza’s left opposition is that its militants tend to prefer the status quo of coalition and not the new horizons of party-movement, which involves more dirty work.

The compromise on congress deciding each time whether to appoint presidential leadership or delegate it to the central committee should be seen as an innovative measure, though I would rather have preferred a dual leadership consisting of a presidency appointed by the congress and two co-chairs and a secretary appointed by the central committee.

An interesting part of the article dealt with the right-populist but anti-fascist Independent Greeks. Previous discussions in the Weekly Worker criticised the ‘workers’ government’ framework called for by the Comintern, but I think balanced lessons from that can be applied to this possibility – a communitarian, populist front beyond the collaborationism of popular fronts and sheer hypocrisy of united worker fronts. Their leader, Kammenos, has aspired to be a defence minister and, if lessons are to be learned from Chile, this is a dangerous concession. However, giving him or politicians like him a Revenue Ministry portfolio (distinct from Finance) could give a “workers government” teeth with which to call tax evaders unpatriotic, especially the more upper-class ones.