Political life after the Communist Party

In 1991, Kate Hudson was one of the leaders of the left opposition within the Communist Party of Great Britain that unsuccessfully attempted to prevent that organisation’s dissolution. Here she writes on political life after the Party.

In 1991, Kate Hudson was one of the leaders of the left opposition within the Communist Party of Great Britain that unsuccessfully attempted to prevent that organisation’s dissolution. Here she writes on political life after the Party.

For me, it all began with class. My grandfather, Percy Hudson, worked in the coke ovens at Horden Colliery in County Durham. My father spoke of Percy’s brothers working underground in the narrow coal seams five miles out under the North Sea, lying in spaces only eighteen inches deep, often in water. The physical strain of the work led to their early deaths, in their late thirties or early forties, mostly of heart attacks. Percy was the lucky one. He worked on the surface and survived into his sixties. If class identity can be a primordial instinct, class solidarity an emotional compulsion, then I’ve got it in the very fibre of my being. For Percy and many others in that community, class meant the union, whether of miners, mechanics or cokemen. The union was a matter of dignity and pride which dominated life, from the pit, to the miners’ hall, to Horden ‘Big Club’ – the working men’s club – and even to the ballot box. For class also meant the Labour Party – and union and party were so interlinked they were often indistinguishable. The Party dominated politics at every level and was fundamental to the people’s lives, representing them and their advancement. My uncle Fred was constituency agent for Emmanuel Shinwell, who had taken the local Easington constituency from Ramsey MacDonald in 1935, and held it until his retirement in 1970. Communists were a rare, eccentric ‘other’. The Durham mining village Chopwell was known as Little Moscow because of its strong support for the Communist Party, boasting street names such as Marx Terrace and Lenin Terrace. But Chopwell was very much the exception that proved the rule.

My father, Tom Hudson, broke away from the pit. Percy was one factor in this – no miner wanted his son to go down the pit and the union’s emphasis on education and the advancement of the working class made the goal of further education and alternative aspirations possible. He and his wife Jenny worked to ensure that Tom stayed on at school until eighteen rather than leaving at fourteen or fifteen as others did during the 1930s. Instead he went to SunderlandArtCollege. The other factor was the war. Tom was called up in 1940, fighting in Burma, experiencing battlefield horrors at Kohima, and the suffering and loss which profoundly shaped him, as it no doubt did all those who survived, having seen their comrades blown to pieces. But at least as powerful in its political impact, was his experience – having unusually survived two years at the Burma front – went he was sent on leave to Calcutta. This was during the Great Famine, the ‘man-made’ famine, where thousands lay dead and dying of starvation in the streets. The famine was the result of the manipulation of the price of rice and the guilt was at the door of the British imperial masters. The combined experience of Burma and Calcutta reinforced Tom’s anti-war and anti-imperialist views and he held them strongly throughout his life. But he never joined a party or became politically active in the conventional sense. After the war he went back to art college and eventually entered a career as both an artist and an art educator. But his politics was fundamental and shaped my world view significantly.

When I eventually joined the Communist Party, he told me that he had read and sold Labour Monthly – edited by that formidable anti-colonialist, Rajani Palme Dutt – with friends from the Young Communist League and had been chased by fascists as he did so. What I didn’t know until much later was that he thought the Russian Revolution was the most important event in human history. I don’t suppose he ever described himself as a communist but without doubt his humanity – and his confidence in humanity to advance – were absolutely shaped by his class and anti-imperialist values. On a more practical level, it was his visit to the Soviet Union which meant that I first met the little yellow booklet that was The Communist Manifesto and became acquainted with Soviet-produced Lenin pamphlets.

The Communist Manifesto was a revelation to me. Such clarity of thought, such principle – and such common sense. I can honestly say that since my first teenage reading of The Communist Manifesto, I have never looked back. It has shaped my view of both class and party. Not only the necessary role of the working class in the universal emancipation of humanity, but the sine qua non of communists – to have no interests separate and apart from those of the working class. What better call to arms against sectarianism than that? What clearer guide to action in every political decision or dilemma?

My father’s other political gift was to help me understand that the real driver for change was love of humanity not class hatred. For many years as a child, this was literally conveyed to me in a completely visual way. On a poster on my father’s bathroom wall, was a photograph of Che Guevara with his simplest yet most profound statement: ‘Let me say, at the risk of seeming ridiculous, that the true revolutionary is guided by great feelings of love’.

Joining the Party

So it was that when I went to university in 1977, the first thing I wanted to do was join the Communist Party. I’d already had some exposure to it at school – a friend’s parents were members and I had read the Morning Star and been to a Party event. This was a celebration of the 59th anniversary of the Russian Revolution held at Wimbledon Town Hall, featuring Harry Gold and his Pieces of Eight – a popular dance band that quite extraordinarily enhanced the mystique of the communists for a seventeen year-old schoolgirl. My attempts to belong now hit the first hurdle. When I entered the freshers’ fayre in my first year at university, the Communist Society stall was staffed by rather older sophisticated students talking amongst themselves. I was much too shy to make the approach. A moment later I passed the Labour Club stall, where a friendly young woman pressed me into not-totally unwilling membership. After all, although Labour was not my goal, nevertheless it was safe, it was family.

Of course student life in the late 1970s was affected by a wide range of cultural and political factors: from punk to Baader-Meinhof and the catastrophe of the attempts to import guerrilla tactics into western urban political conflict; from the apparently unchallengable power of the trade unions to the onset of Thatcherism that would smash militant labour and the Left in a brutal class battle; and the impact of the simultaneously empowering and potentially fragmenting upsurge of the struggles for black, women’s and gay liberation. As my university years progressed, the attraction of the more radical leftist groups was strong. The International Marxist Group – a post-1968 orthodox Trotskyist organisation – was by far the most theoretically developed, and particularly attractive to me around the questions of Feminism and what is now called identity politics. The SWP student organisation was noisy and enthusiastic, with deceptively simple answers to complex problems. But they really ruled themselves out for me because of their fence-sitting position during the Cold War – neither Washington nor Moscow but international socialism. What did that mean when the fundamental struggle was against imperialism? It meant dead-end contortions over crystal clear issues like Korea and Vietnam.

My final decision on political affiliation came in 1979. Enough of the victories were still with us for me to feel that the movement was in advance, not facing imminent defeat on a massive scale. At that time the Communist Party had getting on for 30,000 members. It was a major political player in numerous ways. Where, I asked myself, would the working class go politically, if there was a further turn to the left in Britain? Would it be the IMG or the SWP? No, I concluded, it would be to the Communist Party. And so I joined.

Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the different elements of the Left were largely defined by their analysis of and attitude to, the Soviet Union. 1991 changed all that and a very different left political landscape began to emerge, where the fault lines were redrawn and from the wreckage emerged new left, anti-capitalist forces, usually built around the Communist Parties, or lefts of Communist Parties that had not capitulated to capitalism or seamlessly morphed themselves into social democracy. The situation in Britain was actually quite unusual – that a CP should wind itself up and abandon the Marxist project for human liberation. Elsewhere, communists rose better to the challenge of taking the principles forward in a new political context. The Communist Party had been an anchor to the left in British politics and with its dissolution a small yet extremely significant part of the political landscape was vacated and has not yet been filled. The role of the Communist Party as the far left of the political mainstream, with its capacity to lead, innovate and influence, through its relations with the trade unions, civil society organisations and campaigns – not to mention the left of the Labour Party – stood in stark contrast to the marginal and isolated positions of the ultra-left organisations. The leadership of the Communist Party, which chose to terminate that historic role, dealt a body blow to left politics in Britain and also ensured that the British working class movement would not only be devoid of any effective leadership, but would also stand outside the positive left political developments which were to take place in western Europe in the 1990s. These were largely in the orbit of communist parties that were looking for new ways of taking forward Marxist politics, rather than attempting to consign them to the dustbin of history as the British party leadership had done.

It always struck me as particularly reprehensible that a number of those who had chosen to lead our Party – and would clearly already have known about any crimes and misdemeanours perpetrated by our Party or any other – should have gone into an agony of political self-flagellation in 1989 and seen it almost as a moral duty to wind up the Party. This was to fail to understand the political role of the Communist Party and the historical necessity for it in the advancement not only of the working class but of humanity as a whole. That in turn led to a failure to understand the real significance of the events of 1989 and 1991 and what action was actually necessary as a result. In the view of many communists and others on the Left, who remained committed to the revolutionary transformation of society in the interests of the whole of society, the defeat of the Soviet Union was a catastrophic event for humanity and the way forward was clear. It was essential to regroup and rebuild the international workers’ movement. Others could choose to give up, to capitulate to capitalism and many did – like much of the party leadership, succumbing to the ahistorical nonsense peddled at that time, like the ‘end of history’ thesis of Francis Fukuyama. He argued that the very process of historical change was now over, because capitalism had ‘won’. Even the most cursory survey of the last twenty years exposes that as triumphalist drivel not worth the paper it was written on.

So why did I take the view that the way forward for humanity lay with the organised movement of the working class, when so much appeared to suggest that the attempt to build workers’ states had been a failure? And beyond that, if those states had failed, why did I think their collapse was catastrophic? For me, the answer lay in one of the most basic propositions of Marxism: because the victory of the working class is the necessary and fundamental step in ‘universal human emancipation’, each advance of the international working class benefits the whole of humanity. And every major defeat of the working class will throw back not only that class, but the whole of human civilisation and culture. This is something that the Communist Party leadership had lost sight of. I well remember talking with one leading member towards the end of the Party who insisted that the Party should not prioritise class as an ‘oppression’ over other ‘oppressions’. This led to the worst kind of shopping-list politics, but more importantly missed the fundamental point about the working class and its potential historical role in liberating society as a whole, not just itself. It was that relationship between the working class and the future of society that was the basis of Marx’s socialism. In Marx’s view, a class could only lead society if it represented not only its own interests but the wider interests of society. As Marx wrote in The German Ideology: ‘The class making a revolution comes forward from the very start… not as a class but as the representative of the whole of society, as the whole mass of society confronting the ruling class… Its victory, therefore, benefits also many individuals of other classes which are not winning a dominant position… Every new class, therefore, achieves domination only on a broader basis than that of the class ruling previously…’ But, having achieved the leadership of society, the ability of previous leading classes to represent wider interests of society – their universality in Marx’s expression, or hegemony in Lenin’s – was limited and ultimately negated by conflict between their particular interests and the further development of society.

So, the great bourgeois revolutions of the eighteenth century, by striking down feudalism, advanced not only the bourgeoisie but also all other classes oppressed by feudal social relations. However, after 1848, the class interests of capital more and more conflicted with the general development of society. The result was increasingly violent economic and political upheavals which culminated in the world wars of the twentieth century. From that point on, far from representing the universal interests of human civilisation and culture, capital threatened to extinguish them. This then posed the question of what class could prevent the progressive advances which humanity had made – like limited franchise, limited labour rights, limited education and so on – being destroyed. Indeed, what could advance them?

The answer was given in Russia’s October 1917 revolution, taking that country out of the First World War and providing an objective base of support for every subsequent struggle against capitalism and imperialism. The Russian revolution demonstrated in practice the historical role of the working class which had been theorised by Marx 70 years earlier. This is from volume six of the Collected Works:

‘All preceding classes that got the upper hand, sought to fortify their already acquired status by subjecting society at large to their conditions of appropriation. The proletarians cannot become masters of the productive forces of society, except by abolishing their own previous mode of appropriation, and thereby also every other mode of appropriation. They have nothing of their own to secure and fortify… All previous historical movements were movements of minorities or in the interests of minorities. The proletarian movement is the self-conscious, independent movement of the immense majority in the interests of the immense majority. The proletariat, the lowest stratum of our present society, cannot stir, cannot raise itself up, without the whole superincumbent strata of official society being sprung in the air.’

So for Marx, the working class was the most universal class in history, because the accomplishment of its specific class goals necessitated not only the liberation of itself but the liberation of the whole of humanity. But, to accomplish its historic role the working class has to become organised and conscious of it. As Trotsky put it, in In Defence of Marxism: ‘The Marxist comprehension of historical necessity has nothing in common with fatalism. Socialism is not realisable “by itself”, but as a result of the struggle of living forces, classes and their parties. The proletariat’s decisive advantage is the fact that it represents historical progress, while the bourgeoisie incarnates reaction and decline.’

So for me this was absolutely fundamental. Only the working class can emancipate humanity – it cannot be done by the bourgeoisie, the radical intelligentsia, nice people wanting to organise a ‘good society’, or some inchoate new notion like ‘multitude’. But that emancipation is not going to happen by magic. It requires the working class to be organised and conscious of its role. That had always been the challenge for communists and that remains so today. It is not surprising then that I consider the dissolution of the CPGB to have been a political error of such vast proportions.

Post-1991

Thus the need since 1991 to work for left regroupment to advance the working class and ultimately the whole of society has been an absolutely clear goal for me as well as many others. For myself, there have been two ways in which I have been engaged with it. The first is with the wider European process which has largely taken place in a political party context which I have had some engagement with, both as an academic working in that field and in relation to my own position as a former leading activist in the CPGB and subsequently a member of the Communist Party of Britain. The second is in what I have seen as a de facto realignment process which has taken place in Britain, primarily outside and often in spite of the party political structure, namely the anti-war movement after 9/11.

The former development, the post-1991 European left realignment process, has occupied a large part of my theoretical and practical political work over the last twenty years. It is not widely recognised or understood by the left in Britain, who are generally obsessed by the minutiae of their own relations with other marginal forces, so it needs to be elaborated upon here. Unlike in Britain, a new European Left emerged in the early 1990s and went on to have some considerable success in a number of key European states – France, Germany, Spain and Italy, amongst others – playing a role in, or in support of, national or regional governments. This Left could be simply described as a converging political current of Communist Parties, former CPs and other parties to the left of social democracy. But it was also a complex process and from a communist point of view, part of its significance was that it embraced only one part of the communist movement.

From 1989 it was possible to see three trajectories which communist parties – or sections of them – variously followed. Firstly, those who chose the path to social democracy, exemplified by the majority grouping within the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and often favoured by those from the Eurocommunist tradition. The majority in the leadership of the CPGB – although not of the membership – was enamoured with the PCI, and followed the ‘transformation’ route. The balance of forces being what it was, this actually meant that the CPGB became a bizarre think-tank on the road to radical Blairism, hung up on tactical voting and other matters irrelevant to universal human emancipation.

Secondly, there were those parties who failed to recognise the new political situation, or whose response to it was to dig in and defend the old traditions. The key mistake was to think that the essence of communism was defined by tradition and formula rather than by how actually to advance the anti-imperialist struggle in the current moment and that this might involve the same principles but different strategy, tactics and methods. In reality these parties often became nostalgic communist sects, living in the past, tied to a disappearing electorate and in irreversible decline.

The third category, which is the one that has actually had a positive impact on economic and social struggles and advanced the working class over the past twenty years, was those parties that formed the new European Left and which had two particularly significant characteristics. Whether or not they retained the name communist, they certainly retained a commitment to Marxist politics, to an anti-capitalist perspective, taking account of the realities of European and world politics at the end of the twentieth century. Many also showed a considerable capacity for open political debate and renewal, drawing on and opening up to feminism, environmental and anti-racist politics. But most unusually, in many cases these parties either initiated, or participated in, a realignment of left forces, often working with organisations that would previously have been regarded as politically hostile. This included allying with or even merging with the electorally insignificant, but very active, new left organisations – often based on a Trotskyist political orientation – which had expanded dramatically after 1968. Such groups participated in Spain’s United Left, merged with the left wing of the Italian Communist Party to found the Party of Communist Refoundation, were included in the electoral lists of Germany’s Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and eventually joined its successor party, Die Linke, and were invited to participate in common actions and debates initiated by the French Communist Party.

Before 1989, such cooperation would have been inconceivable but the defeat of the Soviet Union also had a significant impact on much of the mainly Trotskyist and other new left parties that had emerged from the 1968 radicalisation in Europe. Some of those drifted off to the right, but many, whilst being left critics of the Soviet Union, concluded that its overthrow by capitalism was a disaster and were prepared to work with communist parties and their successors in the post-Soviet world on the basis of an anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist perspective. Disagreements about the Spanish civil war seemed less pressing than the neo-liberal onslaught on the welfare state and the developing world. This approach was encapsulated by PDS Chair Lothar Bisky at the party’s Fourth Congress held in January 1995: ‘…together we want to tap and use the ideas of communists such as Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Nikolai Bukharin, the old Leon Trotsky or Antonio Gramsci. It is undisputed that we commemorate those communists who were persecuted and killed by the fascists. Yet it is also our duty to honour those who were killed by Stalin’.

The forerunner of the new European Left was Izquierda Unida (IU), the United Left, in Spain. Its early development was the result of the particular conditions in Spain following the demise of Franco’s dictatorship and the early collapse of the Spanish Communist Party (PCE) as a result of the Eurocommunist policies of the late 1970s. It originated in the campaign against Spain’s membership of NATO, which was the subject of a nationwide referendum in 1986. A broad committee, which included communists, pacifists, feminists, human rights groups, Christians and the far left – with the exception of the former Eurocommunist PCE leader Santiago Carrillo who refused to participate – coordinated a vigorous anti-NATO campaign. In spite of media saturation and huge pressure for a Yes vote, it won 43% of the vote. This anti-NATO campaign provided the basis for the founding of IU in 1986. Its main components were communists, left dissidents from PSOE – the Spanish socialists, the Republican Left, and some smaller left groupings, subsequently including members of the Trotskyist Fourth International. Initially it made little advance on the PCE’s election result of 1982, but by October 1989 it had more than doubled its vote with 9.1% of the vote. The political composition of IU became something of a pattern in the shaping of the new European left over the subsequent years. The parties of this new current have made a significant impact on western Europe over the past twenty years and have been the chief exponents – and achievers – of advances for the working class and the population more broadly, whether it be the achievement of the thirty-five hour week in France or a range of other socially progressive legislation in the context of socialist, environmental, gender, race and human rights policies.

Unfortunately Britain has been outside this new mainstream of the European Left because of the absence of a communist party willing to face the realities of building an alternative vision and reality of a socially solidaristic Europe. The nearest we have seen to the European attempts to transcend previous divisions and build a new political entity to address the new political context that we have faced, particularly in the last ten years, has been the Respect Party. Respect was an attempt to build a new political coalition based around some of the forces which brought the anti-war movement to national prominence and indeed to global significance. Its outstanding achievement was to draw sections of the Muslim community that had been radicalised by the Iraq war into a wider socially progressive coalition with elements of the far left. But Respect was unable to make a major break into significant political and electoral support, partly – it would appear to an outsider – due to tensions within and between its far left components. But it was eminently understandable that such an initiative would take place, given the extraordinary range of social and political forces that were brought together by the anti-war movement in the years following 9/11. My own involvement in the leadership of the anti-war movement came about as a result of my position in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

CND

In the years after 1991, the absence of the CPGB, for which I had worked as well as being a member and activist, left me in search of a new political focus in which to invest my energies. Whilst I engaged in a number of campaigning activities, it was only really towards the end of the decade that I finally found the issue which was to motivate me as intensely and comprehensively as the Communist Party had done – the struggle for peace and, in particular, against nuclear weapons. Like hundreds of thousands of others I had protested against cruise missiles in the early 1980s, straying into the orbit of CND, as well as spending time at Greenham, that iconic and life-changing assault on male militarism which was in turn subject to brutal political and physical attack by the British state. Like most of those mobilised against nuclear weapons in the 1980s, I strayed back out of the issue after 1989 as the end of the Cold War made us think that nukes had somehow gone away.

But as the 1990s progressed it became clear that we were not witnessing a new world order of peace and global harmony. Whilst the Warsaw Pact had been wound up, NATO had not and indeed was in the process of expansion. Just days before the first regime change war masquerading as ‘humanitarian war’ – NATO’s attack on Yugoslavia in 1999 – three former Warsaw Pact countries, Poland, Hungary and the CzechRepublic, were admitted to NATO. At the same time the US was pursuing ‘national missile defence’, a new iteration of Reagan’s ‘star wars’ system of the early 1980s, designed to give it the ability to end the strategic balance between the US and Russia by ending the threat of mutually assured destruction. If the US were to launch a first strike attack against Russia, the missile defence system would be able to knock out what was left of Russia’s retaliatory forces. Not surprisingly Russia reacted very negatively to the development of missile defence, as the Soviet Union had done in the 1980s, and as it continues to do today, in response to Obama’s more subtle version of the system. The end result of these developments was that I became involved in CND, first as Chair of London Region CND and then as a national vice-chair – a post to which I was elected in September 2001, just days after 9/11. The context of our anti-nuclear campaigning was transformed fundamentally, and CND took its place in the leadership of a new anti-war movement, working not only to prevent a disastrous war but to take nuclear weapons campaigning out of its ghetto and into a public understanding that nuclear weapons are about war – that they are not just a particularly nasty piece of military kit. And of course engagement in the anti-war movement also meant introducing a radicalising new generation to our nuclear issues too and brought CND thoroughly into the twenty-first century.

Of course for me as a communist, anti-war campaigning was in my political blood. The origins of the communist movement lay in the struggle against imperialist war in 1914 and the fundamental principle of international working class solidarity originating in Marx and Engels’s statement in the Communist Manifesto, ‘Communists everywhere support every revolutionary movement against the existing social and political order of things…Let the ruling classes tremble at a communist revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win. Working men of all countries, unite!’ The communist view, which I continue to hold, is that workers have a bond with class not nation, and therefore their allegiance and interest lies with international proletarian solidarity and not with support for their national bourgeoisies.

The origins of the communist movement were to be found in defence of this principle against the majority of the workers’ movement in the context of the First World War. During the years of the Second International, founded in 1889, all kinds of debates had developed, around reform and revolution, around the participation of working class parties in bourgeois governments – not an abstract debate given the rise of the massive Marxist-based Social Democratic Party in Germany. But by the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, after a wave of increasing radicalisation which included the 1905 Russian Revolution and general strikes in Western Europe for universal suffrage, divisions began to emerge within the Second International. The declaration of war on 14th August 1914 finally separated the revolutionaries, such as Lenin in Russia and Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in Germany, from revisionists such as Karl Kautsky.

The Second International tradition had been anti-militarist and internationalist, opposing the workers being cannon fodder for bourgeois governments. But within hours of it starting, almost all socialist parties had backed their own national war efforts. There were exceptions to this, in the Balkans and Russia, and amongst tiny minorities in other countries. But the French Socialists and the German SDP backed the war, even voting for war credits. The revolutionary wing of the movement began to organise itself. In September 1915, following a wave of working class protests against the war, the Zimmerwald Conference convened in Switzerland where the Left from the Socialist International agreed a position of opposition to the war. In 1916, the Socialist International was dissolved and in 1919, the Third, or Communist, International was formed.

In this context it was hardly surprising that when a new anti-war organisation came into being in September 2001, the Stop the War Coalition (STWC) founders sprang from a range of left traditions, some from far or ultra-left groups. CND nationally did not join STWC as the membership and support for CND was socially and politically far broader than the framework in which STWC was founded. But CND worked closely in alliance with it to oppose the war and occupation of Iraq and the wars on Afghanistan and Libya. STWC very rapidly won massive and broad support and concerns by some CND members that the left-wing leadership of STWC would take extreme positions that would alienate its broad support turned out to be unfounded. CND and the STWC have also worked with Muslim community organisations, primarily in the early years with the Muslim Association of Britain and subsequently with the British Muslim Initiative. This triple alliance in which each organisation has unique mobilising capacities, together organised the largest ever demonstration in Britain, of around two million, against the war on Iraq on 15 February 2003.

One of the remarkable features of the anti-war movement had been its continued unity of purpose – ten years on it has not been divided, in spite of the different traditions from which its components hail. What has interested me particularly, in my experience as an officer of the STWC for most of that time, is how the political components that have come together in many of the new European left parties – the realigning post-1989 of the left – have actually come together in a similar way in the STWC. It has been an interesting and very positive experience for me, as a communist, to work in an officers’ group – which has met virtually every Friday at 8.30am for the last ten years – which includes not only other communists, but also left Labour, Cliffites, and Trotskyists of various backgrounds. Together we have always been more than the sum of our parts and a commitment to the shared values of universal human emancipation has generally enabled us to overcome sectarian interests. It is to be hoped that we will maintain this unity when differences of analysis arise, as they have done recently over the war in Libya and protests again the Syrian government.

But of course there is more to being a communist than being anti-war. The chief struggle in Britain, as I write this chapter, is against the cuts imposed by the Tory-led coalition government. Whilst mainstream economists can clearly articulate the alternative to the cuts agenda and argue persuasively for an investment, growth-led recovery, the Labour Party leadership seems as yet unable to respond adequately to the onslaught on working people’s living standards which has nothing to do with economic necessity and everything to do with finishing the work started by Thatcher, of smashing the welfare state and a full introduction of the free market on every level. As a result of her attacks on the trade unions – the organised working class – in the 1980s, the class is weakened, and although there is an increase in working class militancy which has seen the largest trade union mobilization ever in March 2011, there is as yet no sustained and coordinated opposition to the government agenda from the labour movement to build a hegemonic anti-cuts position in a society where the vast majority are negatively affected by them. This is where in decades past the Communist Party would have played a key role – leading from the left and bringing some measure of unity to the Labour left and trade unions, clearly articulating a people’s alternative. The unity of the left achieved in the STWC has not yet been redeveloped for the anti-cuts movement, not least because the natural leaders of such an initiative are the trade unions which organise workers in economic struggle. Small wonder that the absence of a communist party with that political weight, that anchor to the left of the mainstream of the movement, is such a blow to our society. But for those of us that feel its loss, and who want nothing more than to fight for the class, and for the advance of all humanity, there can be no better words than those of the US working class activist Joe Hill: ‘Don’t mourn – organize!’

This article was published as ‘A Political Error of Vast Proportions’ in 2012, in After the Party, edited by Andy Croft and published by Lawrence and Wishart.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

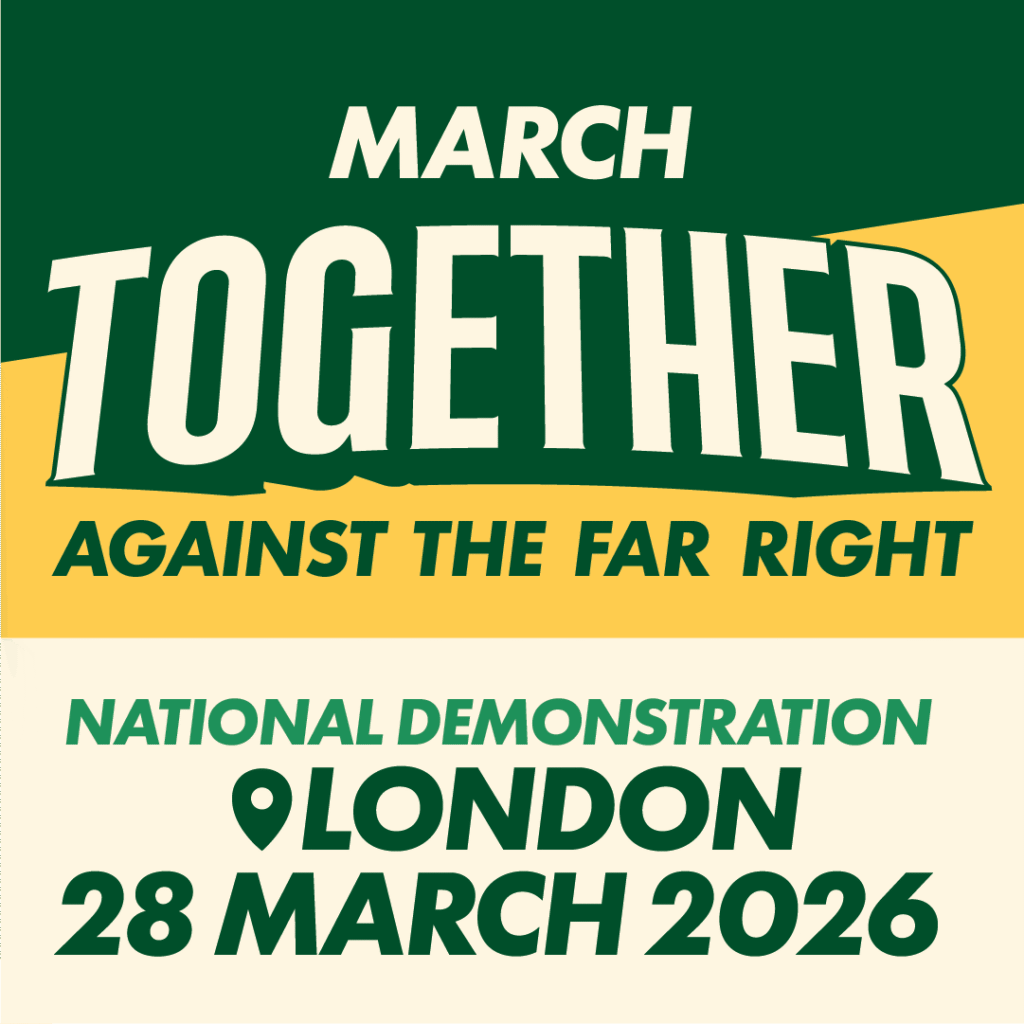

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.