New possibilities for a realignment of the left

There is a crisis at the heart of the left in Britain. It is most acute in the SWP, where the bureaucratism and lack of democracy have exploded into an incredibly damaging public explosion around the handling of a rape allegation against a senior party leader. But this is also partly reflective of a wider chronic problem of cyclical decline, increasing isolation and the blight of sectdom which inflicts the entire left. Bureaucratic domination of a revolutionary organisation is nothing new, and it is always caused to some degree by the weak relationship to the working class and other popular forces.

The fact is that the British left is stale and largely unconvincing to wider society – including the working class activists that socialists so desperately want to relate to. I have written at length about the problems and won’t dwell on them again here, because something far more important is happening. In the maelstrom that sections of the revolutionary left are going through recently, combined with the urgent need for a rejuvenation of the left that goes beyond building the sects – we have an opportunity for an new alignment of the radical forces in this country.

The broader left

In fact there is the possibility of two quite distinct but naturally overlapping processes of realignment to take place. The first is towards a British-style Syriza, an organisation which brings together reformists and revolutionaries into a political coalition which can present both a credible alternative at the elections and as a new force in the unions, communities and workplaces. It is necessary to preface these comments with the reality that so far it is not clear what fulcrum such a new initiative would emerge – for instance we don’t have a sizeable post-Stalinist, Eurocommunist organisation to build it around, we don’t have a large revolutionary organisation growing larger and able to transform itself into something bigger and broader. Having said that. just because we don’t have a clear route to it does not mean that route is not open, we just can’t see it yet. There is a desire among quite large layers of the population for a break from the stale three party system and something that captures a more progressive mood in politics. We can reach out to those people if we do it in a serious way (i.e. not just an electoral coalition run by a Trotskyist group that is willing to pull the plug on the whole thing at a moments notice).

if such an organisation were to be built it would need a clear anti-austerity programme that can take steps to break the frustrating logjam of mainstream politics. As such it could aim to unite radical left reformists with revolutionaries to try and create a new consensus in British society – away from neoliberalism and market domination and towards wealth redistribution, socialisation of industry and banking and towards a transfer of power back towards “ordinary” people. Such an organisation would have to learn the lessons of other attempts on the European continent to create similar parties/coalitions which ran into difficulty when mainstream started talking left to get re-elected, it is not an inevitable problem to face but it is a factor on creating a clear radical force that won’t just lose ground overnight to a temporarily revived left reformism.

But most importantly it would have to learn from the experience in Britain. Many activists are understandably jaded by failed attempts in the past – Arthur Scargill’s Socialist Labour Party, the Socialist Alliance and RESPECT – all serve as reminded of how the left can get it spectacularly wrong. Some of the unprincipled manoeuvers that went into RESPECT still bear their scars, and we have to honestly be clear about what was wrong about our own practices and what could be better (for instance, giving the first conference 45 minutes to discuss the founding principles of the new coalition was clearly a bad idea). More recently in Ireland the tragic split in the United Left Alliance still shows that it is all too easy to turn gold into lead because some sect or other throws its toys out of the pram. Nevertheless just because we got it wrong in the past does not mean it will always be that way – the important thing is to identify how the problems occurred and take conscious steps to overcome them. A necessary beginning is to overcome the narrow interests of this or that sect and have a commitment to the wider organisation from the beginning.

Such a project of a broader left would have a ‘dynamic tension’ in the core of it from the beginning – the tension between reform and revolution. Some say that this strategic difference has been “resolved by history”, that only a revolutionary programme can guarantee an end to capitalism. This may be the case, but history seems to have “solved” the contradiction between socialism and capitalism on a higher level, that is capitalism won – strategic debates around reform or revolution are – in the present crisis, eclipsed by a more existential question of whether an alternative to austerity is even possible at all. In this situation a coalition of progressive forces to fight for anticapitalist ideas rooted in social solidarity and undermining the power of the ruling class would be a great step forward, no matter if it was limited in the final analysis of a future revolutionary crisis.

A revived revolutionary left

But there is a second possibility here, connected to the longer term issue of not just being anti-capitalist, but abolishing it as a social and economic system. Right now the SWP opposition are fighting to democratise their party, and I wish them well in that. But there are only two ways their fight can end: either they win, or they will be forced out by the spiteful leadership. Either way the hegemony that the SWP’s way of working has had over the far left is being broken. A new Marxist, revolutionary organisation could emerge which breaks from the bad practices of the past and offers a hope for a stronger and more dynamic force on the international left. Certainly it would be a missed opportunity if people limited their ambitions to building alternative versions of the already existing left grouplets. We have to think more intelligently than that.

In thinking about this we also have to get our heads around the reality that there is no transhistorical form of revolutionary organisation good in all places at all times. Bolshevism was very much a product of the conditions in Russia at the turn of the last century and it is clear that a lot of what people understand to be “Leninism” was invented by Zinoviev in the mid 1920s to drive out oppositionist forces. On another level consider whether the anarcho-syndicalist trade unions of the CNT are directly applicable today in a country like Britain? Or whether the mode of organisation coming out of Seattle in 1999 is still a good way to run a social movement over a decade later?

A new organisation which brings together some of best elements of the revolutionary left, the countless people who consider themselves revolutionary but don’t want to join any of the existing groups, and the various networks and groupings of people that have been involved in the struggles in the last few years, would not only be a breath of fresh air, it would help set us back on the path to growth, to more influence and reversing years of decline.

How it has to be different: democracy

A new organisation would have to get away from some of the practices of the past – emphasising centralism over democracy, basing itself on a “my way or the high way” approach or being run by a self serving clique would all have to go. If we are serious about something new, something that is both effective enough to get stuck in where it can and elastic enough to tolerate differences then we could be setting a benchmark for how we could do things better in the future. We could begin to overcome years of splits and dwindling returns on our work and forge a new way forward in a spirit of unity. Tony Cliff himself pointed to some of the problems “the exacerbation of secondary differences, the transformation of tactical differences into matters of principle, the semi-religious fanaticism which can give a group considerable survival power in adverse conditions at the cost of stunting its potentiality for real development, the theoretical conservatism and blindness to unwelcome aspects of reality”. Unfortunately his solution was slightly fatalistic, we have to wait for more new members to join us to change our ways. But what if not many new members join you because of your practice? Or they join and leave quite quickly? Or they join and get absorbed into the bad practices of the organisation (becoming what many people call ‘hacks’), serving only to replicate and reproduce the bad habits of the past.

No, we need to do it differently and better. Such a new organisation would probably start from very general principles at first, would be much more “open” then many of us are used to, but would take steps towards greater unity which sees us consolidating policy and tactics over time. A new drive towards realignment on the left will probably start off looking more like a coalition or a social(ist) movement – don’t forget in the early days of social democracy the importance of the readers group (later, the film club), the parades through town centres, the postering campaigns, activities designed to spread the word and build the muscles of the organisation. It should be an attitude of positively creating space and incentive for such work – create the ground swell or joint work and circulate the new ideas before people start to sit down and perhaps draft elaborate manifestos. We need an intellectual airing of ideas as much as we need activists on the ground.

How it has to be different: leadership

If this is to occur then the understanding of leadership will have to change. No more can we accept that an all-powerful leadership is elected (appointed?) at a conference which decides all questions absolutely. Members have a choice to follow orders, complain after the fact or leave the organisation. We need more bottom up decision making, including every member in the discussion and – yes! – even supporters outside of the organisation on occasion. Ideally, any decision by a leading committee should be seen as the culmination of grassroots discussions and debates, not the source of executive power. Likewise, the leadership should have no powers of political expulsion – that should be left up to local units and working fractions of the organisation. Resolutions and motions should be taken at branch level, referred up through the organisation and crystallised into policy after being given adequate time for debate and amendment.

All year round discussion on politics and policy should not only be “allowed” it should be encouraged. Don’t be afraid of debate! And lets get away from this ridiculous notion that debate and political disagreement always hamper our “interventions” into the class struggle. That is the language of the bureaucrat who wants to shut you up. The open debate on the internet between SWP members over the faction struggle in their party is not a sad indictment of ill-discipline, it is a sign of the times – Leninists trying to constantly stymie this development are reminiscent of King Canute trying to hold back the tide. Clearly such disputes only really break out into the open when comrades feel betrayed by the internal procedures of their organisation, in such a situation outpourings of anger and attempts to rally sympathy for an alternative course of action are entirely understandable – something that would not be remiss of even the apparent paragon of democratic centralism comrade Lenin when he felt that the Bolshevik leadership was on the wrong path. However, if members of an organisation feel there is legitimacy, clear democratic avenues and no gerrymandering going on then they will be less likely to ‘break ranks’ in such a potentially destructive way.

Generally speaking members involved in the work should be the ones that make the decision about that work. This is not a principle but it is best practice. Sometimes people make mistakes, but to make a mistake and learn from it is worth a thousand “over riding” diktats by a central committee.

Moving beyond the Leninist left

At its best a new organisation should reach out to the bridge the gap between the autonomist/left communist tradition and the healthier elements of some of those that consider themselves Leninists as well as people in between – by accepting that we are building a revolutionary organisation which is united around key aspects of the struggle against austerity, against attacks on workers rights, against fascism and racism, part of the rising new movements against sexism, that wants to build grassroots campaigns and initiatives that actually empower people in their own lives (not party fronts that are directed from central office). We have to accept that there will be differences of tactics on a number of questions and we will work out mechanisms to resolve those disputes in a comradely and open way.

To those that are reading this and thinking “that sounds ridiculous, everyone knows that revolutionary politics doesn’t work like that” I would urge you to reconsider that dogmatic and narrow viewpoint. The history of Marxist movements has many examples of times and places when such initiatives were tried – did all of them work? No, but then not all of the rigidly apparently orthodox Bolshevik-Leninist organisations worked either, in fact they tended to fail in an entirely different way. But we don’t want to chose between two roads to failure, we need to find a new road – the one to a much more healthy organisational and political practice. This is not a call for eclecticism, it’s a call for pluralism as a necessary stage of recomposing a healthy revolutionary left. It is a call for us to stick to our revolutionary principles whilst building an organisation that is more condusive to the tasks and conditions of today. It can be done, it must be done.

2 comments

2 responses to “New possibilities for a realignment of the left”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

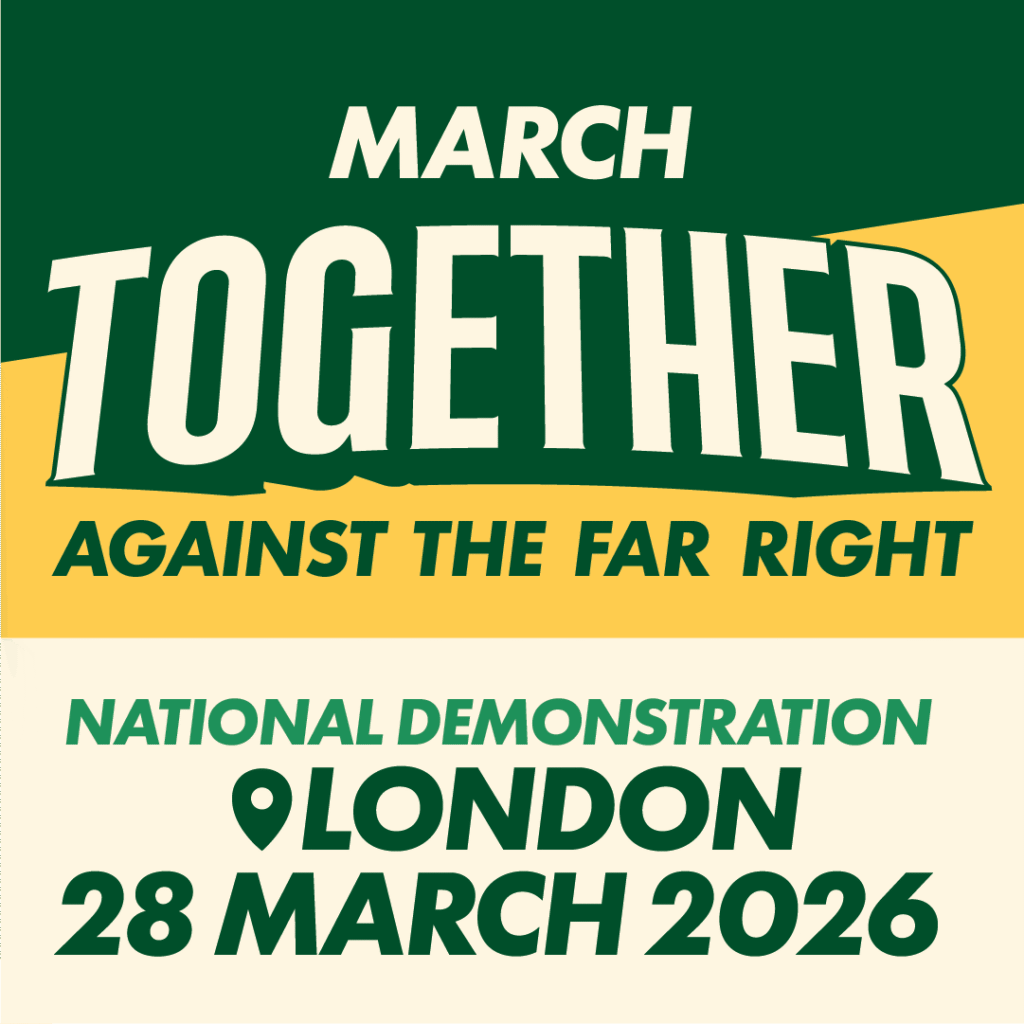

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Great piece! Having an organisation / movement were dissent is protected, but members can agree on some basic guiding principles to orient their activity today seems great.

And, I also particularly liked this: “don’t forget in the early days of social democracy the importance of the readers group (later, the film club)…activities designed to spread the word and build the muscles of the organisation. It should be an attitude of positively creating space and incentive for such work – create the ground swell or joint work and circulate the new ideas before people start to sit down and perhaps draft elaborate manifestos. We need an intellectual airing of ideas as much as we need activists on the ground.”

Thank you!

Greetings from Canada! I too agree with Preeti above: Great piece! There are lessons in James’ article for those of us on the left in North America, as well. It is disappointing to see what is going on with the SWP in the UK. I am a far left union activist with no formal political affiliation only because there are no credible broad left forces out there to throw your energy behind. I have a family with four children, so I don’t have time to waste on a small-minded and parochial project. I have learned mainly from the insights of class-struggle anarchism, but also from Marxism too; even Lenin has lessons for us today. Things have changed too much since the 19th and early 20th century to think we can rely old, pat formulas. I think James is correct, if the right kind of left political project, organization or movement came along interested in building something creative, serious and healthy, I think a lot of us at the grassroots would be willing to help give it life and spread that lively vision to others. As a union activist, I still see too much fear in our workplaces and in our communities. People are cynical and discouraged. It is going to take time to dispel that, but that fear and discouragement will certainly not abate without a large, robust left movement.