Men, women, race, socialism

by Brigitte Lechner

Why does capitalism confine women to the lower steps of the hierarchy in the labour market? Why do austerity measures have gendered impacts? Why do some women debate the merits of pornography but not the powerful industry that drives it to ever more violent expression? How did we arrive at ‘choice feminism’, where everything from prostitution to make-up involves women’s choices that are considered empowering acts of feminism?i No attempts will be made to offer answers but rather to shine a broad beam on the interlocking systems of oppression affecting women throughout time and space: patriarchy, racism and capitalism.

Patriarchy

The historian Gerda Lerner locates the earliest form of patriarchy in the Middle East, during the agricultural revolution between the late Stone and early Bronze Ages, appearing in the form of the archaic state and its basic unit, the male-headed household.ii

Patriarchy is a social system of unequal gender relations and predates capitalism by some 2500 years. Like Friedrich Engels a century earlier, Lerner tracks the historic subordination of women as a social group back to the shift from a matrilineal/matrilocal (mother-right) social structure to one that was patrilineal/patrilocal (father-right). This shift, Engels suggested, coincided with the birth of agriculture and is characterized by men’s increased control of the tools of production and ‘his’ householdiii. There is now broad agreement that women’s subordination did indeed occur during the transition to patrilocality and the social differentiation between men (as a social category).iv Engels was not clear on how this change was effected but Gerda Lerner is, and her suggestions are grounded in material history.

The transformation, says Lerner, unfolded over time and built on earlier practices. For example, the concept of land-use at some point became extended to women. Women had labour and reproductive powers and produced a surplus that could be expropriated by the male who controlled them. An earlier form of the use of women as a resource for wealth creation is rooted in traditional exchanges of women to forge alliances between warring tribes. Such exchanges had the consent of the women initially, but at a later stage male control obviated the need for consent.

Even racism has its roots here. A practice of enslaving the females of conquered tribes already existed. Initially, males were killed and females exploited for their labour and reproductive powers but at some later point the practice of enslavement was extended to males as well. In short, “[m]en had learned how to assert and exercise power over people slightly different from themselves in the primary exchange of women.”(Lerner, p.214)

Tribal kinship relations had earlier on organised production and distribution of collective property, but after the shift this function was reserved for the male head of the family unit who controlled the resources he thus owned with the aim of maximising material yield. “It was only after men had learned how to enslave women … that they learned how to enslave men and, later, subordinates from within their own societies. (…) Thus, the enslavement of women combining both racism and sexism preceded the formation of classes and class oppression.” (Lerner, p.213)

The historic subordination of women, and of ‘conquered’ races, follows from their use-value for the accumulation of wealth. Women, children and slaves could all be exchanged, sold in marriage, rented out in the provision of sexual services, or used as a source of labour power. Gender, racial and social inequality is thus rooted in patriarchy, a social system centred on male hegemony that predates the birth of classes. “The more complex societies featured a division of labour that was no longer based on biological distinctions, but also on hierarchy and the power of some men over all men and all women.”(Lerner, p. 53)

A society is patriarchal, says Allan G. Johnson, “to the degree that it promotes male privilege, is male dominated, male identified, and male centred.v In a male-identified culture all that is good and desirable is associated with masculine ideals: control, strength, competitiveness or rationality; emotions such as vulnerability are abjured as they contradict this ideal. Male-centeredness describes a primary focus of social attention on men and what they do and say; positions of authority in politics, business, economy, law, religion or military are held mainly by men. As to privilege, this refers to “any unearned advantage that is available to members of a social category while being systematically denied to others.” (Johnson, p.5) There is therefore a great variation in the make-up of patriarchal societies throughout time and space.

Revolting women

Women have revolted against patriarchy (and capitalism) throughout history but few accounts were recorded for posterity for reasons listed above. ‘Feminism’ is women’s collective and comparatively recent revolt. A brief history of what is properly termed ‘feminisms’ might start with liberal feminism; it has the longest history. As a movement, its aims centre on achieving equal legal status for women in law, culture and politics. There is great emphasis on individual choice, empowerment and campaigning for reform of the patriarchal system from within. Liberal feminism is rooted in the Suffrage movement of the 19th century as women also mobilized for access to higher education, birth control or property rights. The Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s continued the fight for equal access to education, health, contraception, divorce, welfare and equal pay.

In the US and the UK, the movement was dominated by white women. Black women became subsumed in the concept of a universal ‘woman’, not unlike the way women are subsumed in patriarchal concepts of a universal ‘man’ or ‘mankind’. Black women responded by organising collectively and formulating their own struggles; they understood very early on that they confronted interlocking forms of class, racism and sexism. The manifesto of the Combahee River Collective of 1974 illustrates how the oppressions in Black women’s lives throughout history had given rise to this more complex understanding of women’s subordination.vi

Not so their white sisters, whose movement soon fractured along distinct trajectories. Radical feminism emerged and it was militant. As the name suggests, Radical feminists wanted to get to the root of the problem, the system that allocated rights, privileges and power to the male sex (as a social category). They wanted to abolish patriarchy and the social construction of femininity and masculinity that underpins male domination. In distinguishing between biological sex (female/male) and the socio-cultural roles assigned to each in terms of femininity and masculinity they identified a key mechanism that maintained women’s unequal status, mentally and physically: the value-laden stereotypical conceptual binaries that seemed so natural as to be obvious. Take, for example, the binaries men:hard/women:soft, or men:steely/women:bubbly. The masculine was the positive standard in relation to which the feminine was the negative deviation. In short, proper women are not steely and proper men are not bubbly. Radical feminists also pioneered Consciousness-Raising groups where women from all walks of life could share their experiences of oppression in a safe space. Women-only spaces and the fight against the heterosexual imperative are still on top of their agenda today.

Socialist feminism also grew out of the women’s movement in the 1970s. The class development theory of Marx and Engels was used to explain the systematic material and economic subordination of women. They identified the institution of the family as major locus for the structuring of unequal sexual division of labour and put childcare and domestic labour into the purview of theorists. Reproduction was considered a major barrier to women’s employment; once women had equal access to jobs they would gain the independence and liberation they so desired and deserved.

Marxist feminists like Christine Delphyviiapply the theory of historical materialism Marx used to analyse capitalist exploitation to an analysis of women’s oppression. They therefore emphasise that the relationship between men and women (as social groups) are power relations in which gender, sexuality or sexual orientation play an important part.

Women and socialism

Socialist feminists had, at that time, failed to acknowledge the role of women in social reproduction. As Nancy Fraser puts it, “[w]age labour could not exist in the absence of housework, child-raising, schooling, affective care and a host of other activities which help to produce new generations of workers to replenish existing ones, as well as to maintain social bonds and shared understandings.”viii Women were producers of labour power, reproducers of labour power and producers of unpaid domestic labour power and sexual services all of which are socio-economic activities in the service of capital. Yet only their paid employment was monetised as a component of the capitalism economy leading many Marxian theorists to disregard the non-monetised aspects of their labours in theoretical debates. As a result, the working class was male by default and come the revolution, all women could then be liberated along with the men.

Where feminists challenged the organised Left to integrate patriarchal social theory into their theoretical debates the response more likely than not would be a reprimand along the lines of Kieran Allan’s assertion that ‘class is the fundamental drive’ because racism and sexism is experienced differently according to class. (Allan, p.66) Such viewpoints are evidently reductionist because class is in turn experienced differently according to race or gender whilst race is in turn experienced differently according to gender or class. The three systems of oppression interlock.

Towards an inclusive socialism

That Marx was gender (and colour) blind is understandable. That over 150 years later Marxist feminists are still calling for a theory of capitalism that systematically engages with the insights of feminism, post-colonialism and ecological imperatives less so. The imperative here is one of integration not articulation. This task is ever more urgent now that capitalism has morphed into an aggressive global neoliberalism with peak oil and climate change waiting in the wings. (Fraser, p.56) How shall this be done? Do we conceptualize a patriarchal capitalism or a capitalist patriarchy?

“Capitalism grew on top of patriarchy; patriarchal capitalism is stratified society par excellence. If non-ruling class men are to be free they will have to recognise their co-optation by patriarchal capitalism and relinquish their patriarchal benefits. If women are to be free, they must fight against both patriarchal power and capitalist organisation of society.” (Hartmann, p.101)

Heidi Hartmann calls for a dual vision because we are confronting a combined system that determines gender, race and economic relations in society.ix It should not be a union like husband and wife where Marxism and feminism were one thing and that thing was Marxism. The challenge is to avoid reducing social and political relations between women and men to mere economic relations because dominance and subordination are about more than control of labour power.

Allan G. Johnson also warns against overlooking the “essentially patriarchal nature of economic systems such as feudalism and capitalism” (Johnson, p. 126) because “the status of women has both shaped and been shaped by economic arrangements. Patriarchy and capitalism are so deeply intertwined with each other that some social feminists argue against even thinking of them as separate systems.” (Johnson, p.127-8) In short, both Hartmann and Johnson have in mind a kind of unified theory, the practical consequence of which would be to determine the operational laws and connecting nodes in order to account for overlapping class, gender or race issues that need attention.

Cinzia Arruza concurs that the lack of integration limits both, our understanding and our capacity to intervene in reality. However, she has reservations about a unified systems theoryx. “Although this patriarchal system is intertwined with capitalism, it has its own autonomy. Thus the subordination of women under the patriarchal system, whose origins are pre-capitalist, is used by capitalism for its own purpose.” (Arruza, p.116) Capitalism uses the patriarchal tactic of subordination to confine women to the lower-paid steps in the hierarchy of the labour force, and to expropriate their domestic labour; it makes use of the patriarchal tactic of social hierarchy to divide so as to control. When we refer to the ‘feminization of labour’ in capitalist globalisation we mean many men as well as women are now in low-paid, low-status, casualised jobs.

The concept of ‘intersectionality’ is useful in theorizing identity and oppression. As a study of intersections between forms, or systems, of oppression, domination or discrimination– race, class, gender, sexuality – it is well suited to identify multiple and often simultaneous forces contributing to systematic injustice and social inequality. However, its methodology is not as yet developed sufficiently to identify points of intervention or modes of interaction. There is also a need to conceptualise further the complexities of intersectionality where, for example, a female worker might be victimised by gender but is simultaneously privileged by class or race. xi

Notwithstanding theoretical underpinnings, if capitalism generated class struggles and patriarchy generated feminist struggles there are nevertheless grounds for both groups to be engaging with each other to form alliances for the overthrow of all forms of oppression. Such an alliance may be as challenging for feminists as for socialists. The radical wing of the feminist movement has been crowded out by a non-politicised feminism that works within neoliberal paradigms rather than challenge it. The concept of ‘choice feminism’ is an exponent of this inadvertent collusion – inadvertent, because capitalism as well as patriarchy is lodged in everyone’s head. The challenge is clear:

“As feminists, we need to remember that, in this world, one person’s freedom often comes at the expense of another’s. This includes the West’s exploitation of developing countries as well as issues of class and privilege right here at home. The birth control pill, later hailed as a huge leap towards women’s liberation, was tested on under-privileged women in Puerto Rico before it was allowed to be sold on the North American market. White middle-class women’s choices have always taken priority over the choices of more marginalized women.” (Herizons)

‘Choice’ was the highly politicised concept used in the fight for abortion rights or expression of sexuality. The context was patriarchy. This context has become occluded by the market imperative and if “a woman chooses to work in a strip club, for example, the factors that could affect her choice to do this work—which may include class, colonialism, education, abuse or the reality of living in a culture that objectifies women’s bodies—are neatly erased. No one is forcing her to be there, choice feminism says: If men will pay, why not take the cash?” (Herizons)

Silvia Federici is also critical of political strategies in the women’s movement.xii She finds fault with Radical Feminists for identifying discriminatory practices but failing to relate them to material, historical relations of production and class. Socialist Feminists are viewed as failing to acknowledge reproduction as a source of value-creation and exploitation, relating power differential to women’s exclusion from capitalist developments and failing to account for the endurance of sexism within capitalist relations.

Conclusion

Bearing in mind the intersectional nature of the beast, therefore, the struggle to establish socialism is best built on an alliance between varieties of affected interest groups. Common ground will need to be found, as is evident from The Combahee River Collective Statement:

“We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products, and not for the profit of the bosses. (…) We are not convinced, however, that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation.”

An alliance is a pact or coalition between two or more parties and made in order to advance common goals and to secure common interests. Left Unity can lead the way in creating and maintaining an intellectual and material environment that allows for the exchange of theoretical insights without assigning primacy to class or gender or subsuming race or ecology. The binary imperative is not either/or, it is also/and.

i http://www.herizons.ca/node/519 (accessed 19/07/14)

ii Gerda Lerner (1986): The Creation of Patriarchy. Oxford University Press.

iii Friedrich Engels. The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. First published in 1884.

iv Cinzia Arruzza (2013): Dangerous Liaisons -The marriages and divorces of Marxism and feminism. Merlin.

v Allan G. Johnson (2005): The Gender Knot. Temple University Press.

vi The Combahee River Collective Statement: http://circuitous.org/scraps/combahee.html (accessed 21/07/14)

vii Christine Delphy (1984): Close to home – a materialist analysis of Women’s Oppression. Transl. Diana Leonard, University of Massachusetts Press.

viii Nancy Fraser. Behind Marx’s hidden abode, in New Left Review 68, March/April 2014, p.61.

ix Heidi Hartmann: capitalism, patriarchy, and job segregation (1976), in Maggie Humm (1992): Feminisms – a reader. Harvester Wheatsheaf, p.369.

x Cinzia Arruza (2013): Dangerous Liaisons. Resistance Books

xi Jennifer C. Nash: re-thinking intersectionality, in Feminist Review 89, 2008.

xii Silvia Federici (2009): Caliban and the Witch – women, the body and primitive accumulation. Autonomedia.

2 comments

2 responses to “Men, women, race, socialism”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

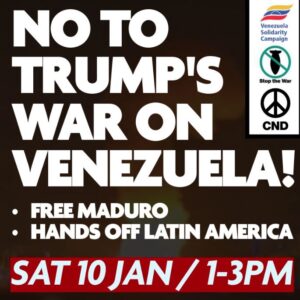

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Very interesting article. However, I have no reservations on unitary theory, which I actually support. The passage you quote does not express my view, but Heidi Hartmann’s position, which I’m presenting in those pages: it cannot be extrapolated from the context and attributed to me as if I were supporting it.

This is a really important article, Brigitte, which summarises, in general terms, where we have come from, where we need to go and the problems involved in so doing. In particular, I would like to see Left Unity adopt the Combahee River Collective Statement that “We are not convinced that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation”.

The only critical comments I would make are these:

1 Why have you ignored or excluded from your analysis the evidence on the early development of patriarchy put forward in David Graeber’s “Debt – the first 5,000 years”? I think his analysis of how the veil arose among male-led households who wanted to differentiate women from their families from urban prostitutes shows, not so much the origins of patriarchy, but how it became institutionalised in dress codes, cultural symbols of differentiation between ‘respectable’ and ‘non-respectable’ women and reflected the tensions between urban and rural life. These cultural developments are vital to patriarchy’s trajectory down the ages; we should not fall into the trap of privileging material over all other historical factors.

2 I think you are on thin ice in arguing that the “practice of enslaving the females of conquered tribes” explains the growth of racism. It may have helped, insofar as these women were differentiated from women who already belonged to the conquering society, but it was when large-scale slavery emerged as a social system that the use of perceived difference became the basis for ordering society according to differential rights.

3 I take issue with your argument that “Socialist feminists had, at that time, failed to acknowledge the role of women in social reproduction”. I recall socialist feminists in Big Flame working in groups like the Hackney & Islington Song Collective that produced material like “I’m not your little woman, I’m your maintenance engineer”, a recognition of women’s role in social reproduction that could not have been clearer.

Yes, you are right that the Trotskyist Left resisted feminism in all forms for a considerable time, but Libertarian Socialism did not – we struggled to find ways of integrating feminist with Marxist analysis and to develop an integrated political practice. In some isolated ways we succeeded, such as occupying pubs in parts of Manchester where women were, even then, not allowed, ‘Reclaim the Streets’ and ‘Women’s Right to Choose’ initiatives; there was a massive internal debate between Big Flame women from the Wages for Housework Campaign and more mainstream Socialist Feminists, which eventually resolved in favour of the latter. The ‘Beyond the Fragments’ initiative of 1980 was an attempt to consolidate the alliances that were then forming between Libertarian Socialists, Socialist Feminists, some Anarchists, supporters of Black Autonomy, Tenants Activists, Gay activists and radical workers. Ultimately, all this was drowned out by the anti-working attacks of Thatcher and the need to resist them, and this politics has never been revived since.

These issues aside, I agree strongly that Left Unity needs to move forward on this as a priority.