Liminal: Working at the boundaries of the Labour Party

A discussion piece by Ian Parker from Socialist Resistance and Manchester Left Unity.

The election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party was a significant event in Britain, changing the terrain of politics at a time when things were generally already shifting to the right. The Brexit result in the referendum and the election of Trump on the wider world stage were symptomatic of this rightward shift. The election presented, and perhaps it still does present, an opportunity, but not if we simply engage in wish-fulfilment about what we hoped it would be rather than look the facts in the face.

We need to know what the election of Corbyn was and what it was not. It was not a transformation of the Labour Party (LP), and phrases like ‘Corbyn revolution’ are inspiring but inaccurate representations of what happened when Corbyn was elected. Neither was it an organised rebellion against the LP apparatus with a broader movement able to build an alternative politics with Corbyn as the public face. Again, that characterisation of the ‘Corbyn movement’ is quite misleading, even though it is understandable that supporters of Corbyn use that phrase as short-hand to describe the process. Neither was it the election of a charismatic populist who was able to inspire people desperate for an alternative; there were aspects of that desperation, but Corbyn was a much more careful and humble figure than some of the talk of ‘Corbyn-mania’ made him out to be. No, it was the election of a decent hard-working left MP who was, first, well-known among the far left inside and outside the LP and, second, respected as an alternative to old crony left politics. The two aspects are interlinked, and they could be as much the undoing of Corbyn now as they were the making of him two years ago.

The first aspect is Corbyn’s record on the left, a supporter of different campaigns, a voice inside parliament and willing to use the resources he had there (physical and symbolic) to link not only with extra-parliamentary politics but also, importantly, to link across to the outside of the LP. This immediately made him a trustworthy figure for many on the left as well as those involved in different solidarity movements, and even connecting with feminist politics (in a more muted way, but even so significantly beyond the scope of usual left LP practice). Those in the left groups and, more importantly, those who had once been involved in left groups mobilised for him. Those were the closest to the organised ‘Corbynistas’ feared by the popular press, and they valued something in Corbyn’s approach after having been sickened by the sectarian and bureaucratic practices of their own past groups. These forces connected with a second aspect.

The second aspect brings in many of those new to politics, suspicious of the political elites, suspicious actually of party politics as such, and not only of the far-left. Their involvement came at a time when the sexual violence scandals in the SWP were still in the recent memory of those starting to be involved in anti-austerity campaigns; the far-left as an organised political alternative to the LP was pretty well dead, written off by many young activists (particularly those drawn into a kind of politics in which feminist and ecological and alternative-movement politics was important). What is crucial here was that Corbyn was not ‘charismatic’ in the old sense, not a ranting populist, not making empty promises; his new supporters are the people who streamed into the LP, but then, after joining, kept away from the branch meetings, leaving space for the ‘organised’ left to move in and, in most cases, mess things up again.

We should be clear about this, however much we admire Corbyn, and however much we hope that something can be built from his election victory; that the election was for Jeremy Corbyn as an individual, and that if and when he leaves the scene, for whatever reason, there is no other ‘Corbyn figure’ to replace him. When he goes, the LP as a left force is likely to wither with his departure. He is a strange ‘anti-charismatic’ figure whose very break from charismatic politics makes him function in an appealing, almost charismatic way. They voted for Jeremy, not for a fictitious ‘team Corbyn’, and as an individual, not part of a movement. He was never, as the chair of the north Manchester rally kept desperately repeating during the first election leadership campaign, to be ‘the man with the plan’. He didn’t have a plan.

The attempts to cobble together a ‘movement’ in the LP after his leadership election have been shambolic. And this is partly because the LP apparatchiks simply repeat the way they usually organise, and partly because they have been joined by left-sectarians, some of whom jumped ship from Left Unity soon as they saw a bigger recruiting ground. Momentum is one key example, but not the only site in which ‘Corbyn supporters’ try and build something after the event of the leadership election, and do actually reinstall exactly the kind of politics that Corbyn opened up an escape from, opened an alternative to. What these attempts to build something after the event around Corbyn have done is actually to fall into a trap, the trap of old-style left ‘party’ politics in its worst sense, of bureaucratic fronts and manoeuvres and stitch-ups.

It is sometimes said that Corbyn is ‘trapped’ by the apparatus. That is true, to an extent, but it is a trap he has willingly embraced. He, for all his strengths, is a Labourite, he sees change in society as being brought about through the LP, and he is surrounded by a coterie of advisors who are in tune with that project, a political project that means humouring the left Trades Union bureaucrats and holding the party together at all costs. This has played out in appalling ways, with John McDonnell and other Corbyn supporters calling on LP activists to respect local council budgets – to set ‘legal’ budgets which effectively administer the austerity and neoliberal cuts handed down from central government – and with Corbyn even at one point compromising on the ‘free movement’ question, even imposing a three-line whip to vote for triggering of Brexit (after not doing the same over the Trident vote). And it is evident in Corbyn’s attempt to win back seats for the LP in Scotland (where the LP is, in some parts of Scotland, so unionist it is willing to stand down candidates in order that the Conservatives will win against the SNP). The LP is a unionist party, and Corbyn does not challenge that (ironically, paradoxically, after his honourable record in support of Irish republicanism).

Space to the left

The effect of the return to the old party politics that Corbyn was elected by many precisely to combat is toxic on progressive politics and on the far left, which should have, which was starting to learn better. It is toxic on progressive politics in the sense that it takes us back to machine-party politics, exactly the politics that those who voted for Corbyn were repelled by. Now they are repelled again. Many of those who joined the LP don’t even need to actively decide to leave because they never really signed up to be part of branch squabbling, but they are drifting away, disappointed already. When they encounter what is going on in Momentum, or when they come into contact with ‘revolutionary party’ alternatives to the LP (like the SWP or its little brother Counterfire) they are then repelled by politics altogether. At best, they go on to join campaigns and anti-party network organising. Let’s hope they at least do that, and we can try to stay in contact with them when they do that.

And it is toxic on the far left. It leaves groups like the SWP crowing at Corbyn’s missteps on the side-lines, waving their papers and ready to try and mop up those who are disillusioned with the so-called ‘Corbyn revolution’. They can even, for a brief period of time, present themselves as a radical alternative to old-style LP politics that the new generation of activists are fleeing from when they flee the LP after their brief time inside it. And it leaves some groups who have gone into the LP with a context in which they are drawn back into their bad old ways, not least dishonest deceptive ‘entrist’ politics in which they rely on ‘front’ organisations and hide their real allegiance.

We had a space to learn how to do things differently, and to learn from those involved in different campaigns. That space was and is Left Unity. Some of the left groups went into LU as a feeding ground and they had a destructive effect there. Groups like Socialist Resistance (SR) did, at least, work in LU openly and in a comradely way, trying to engage with anti-bureaucratic forms of working. It was a context – not perfect, but a good context – in which to connect socialist with feminist politics, in an organised way.

For all the problems with LU, what SR was able to do there, for example, was to configure its public activities – work with others and work with other activists who might hope at some point to be in the same organisation as its own – in a way that was congruent with some of the changes that were happening inside its own organisation. These changes were evident in the embrace of feminism and ecosocialist politics, changes intimately linked to being part of the Fourth International, which gave to those new politics an internationalist anti-imperialist edge. And those changes were manifest in the shift from ‘democratic centralism’ understood in a closed bureaucratic way to what SR now prefers to refer to as ‘revolutionary democracy’. The discussions of ‘safe spaces’ in LU (discussions that were problematic in lots of ways, problematic in the way they were framed by those in favour of them as well as those hostile to them) also connected with those changes. SR learnt what it was like to be able discuss with comrades it didn’t completely agree with about how to build something, and to be open about the disagreements among ourselves. There wasn’t a ‘line’ to be unrolled, and I think SR was respected for that by its old comrades and its new friends in LU.

The real danger now is that revolutionaries are jumping into the LP because it is afraid of ‘missing the boat’, but are jumping into a sinking ship. There are better ways of orienting to the hopes that Corbyn inspired and still, to some extent, inspires, than becoming part of the very LP apparatus that his election put into question. Insofar as there was a Corbyn revolution it lay in opening up a different kind of space in two ways. First, there opened up a gulf between activists and the apparatus – the LP today is two parties and we need to be clearly identified with the activists for whom Corbyn spoke during his leadership election campaigns. Second, there opened a space for exactly the kind of politics that Corbyn was once part of, a ‘liminal’ space that is neither entirely inside or entirely outside the LP. To be ‘liminal’ is to be at a boundary or at both sides of a boundary or threshold at the same time. The boundary in this case is the sharp-drawn boundary between the inside and outside of the LP, and the boundary some of us have unfortunately drawn between the inside and outside of LU. Being liminal also means treating what is happening now under Corbyn as being at an early stage of a process, a transitional point, not treating it as something decided. We don’t know what will happen with Corbyn and the LP, or with LU for that matter, and we need to be open to different possibilities, not abandon our friends in LU, not to burn our boats.

No, we don’t have to be like the control freaks of the SWP shouting from the sidelines saying that we always knew when he would slip up and posing as the fully-fledged alternative to the LP, and, no, we don’t have to be like the Socialist Party, now left in complete control of TUSC after the SWP have abandoned them, rather ridiculously offering ‘advice’ to him as to how he could really make the LP radical. Our place should precisely be in the ‘liminal’ space at the edge of the LP, working with comrades and new activists who have gone into the LP but also linking with comrades and new activists who are still suspicious about the LP, including those who are still in LU.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

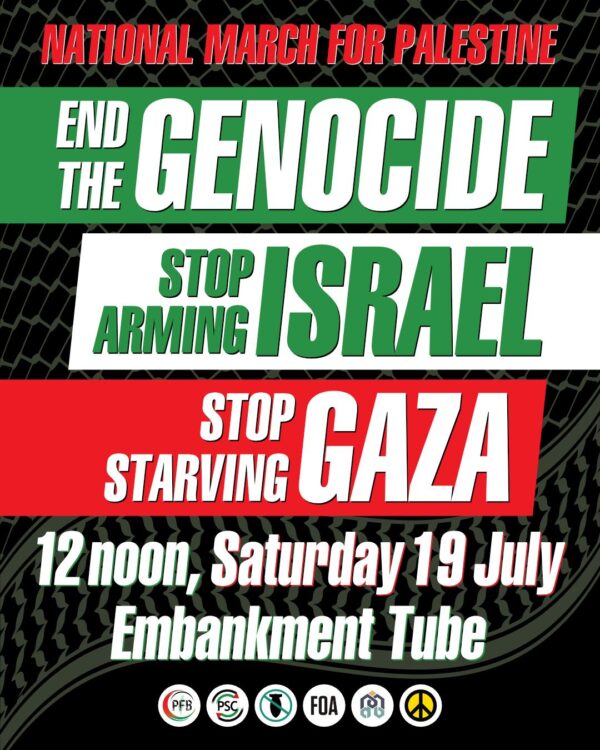

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.