In defence of the economic policy of Left Unity

Pete Green responds to a critique of the proposals passed at conference.

The proposals of the Economic Policy Commission were passed with a few amendments at the Manchester Policy Conference. Unfortunately pressure of time meant that the debate was curtailed and a proposal by Nick Wrack, to extend discussion on a reference back of the whole document, was defeated on a card vote. Nick had, however, contributed a lengthy critique of the Commission proposals to Bulletin Number 3 of the Independent Socialist Network which was handed out to conference participants before the start of proceedings. What follows is a response to that critique in particular (which can be accessed on the Independent Socialist Network website – not to be confused with the website of the International Socialist Network).

Nick acknowledges that “there is much in the submission that is good and should be welcomed”. Yet after acknowledging many ‘valuable points’ he suggests that

“The authors do not seem to know what the purpose of the document is. Is it an analysis of the global economy over the last 30 years? Is it a plan of action to demand reforms? Is it a programme for a future Left Unity government? In mixing all these threads up, the document is confusing. In so far as it addresses the last point the document articulates a programme of partial reform but not fundamental change. This is a major weakness”

As one of the authors I cannot claim to respond on behalf of all members of the commission, although I suspect all would agree that we were not attempting an analysis of the global economy over the last 30 years. My own theoretical position is unashamedly Marxist in inspiration (and I think I was the only person to refer to Marx at the Manchester conference) but I would not demand or expect that other members of the commission endorse that approach. The document itself was the product of a collective process of debate among all the participants in the commission both online and at two workshops in Manchester and London. Some of the amendments which were agreed improved the draft – others did not in my opinion. No doubt there will be more debate to come on the specifics, not least on the vote to reject the policy of a ‘citizen’s income’ which for many was the most controversial issue of them all. Future conferences will have the power to revisit any of the proposals.

Nick raises some specific objections to points which have been changed as a result of amendments (eg abolishing VAT – which the original document stated would happen ‘eventually’ anyway) and mentions some omissions, which he failed to realise would be covered by other commission reports (such as the housing policy proposals we agreed). He makes a specific point about scrapping the national debt which ignores the fact that we need to differentiate between the debt held by pension funds and what would become publicly owned banks and insurance companies and that held by bondholders who are simply a ‘parasitic elite’. On eliminating the latter (or the euthanasia of the rentier as Keynes proposed back in the 1930s) we can agree. But what’s at stake in the ISN critique is less the detail than a question of strategy – less the economics than the politics.

Before addressing the fundamental question – which is how do we achieve a society radically different to capitalism, an aspiration I share with Nick – I first need to address a series of critical points in the order they appear in the ISN document itself.

1. The ‘present crisis’

The criticism here focuses on the short introduction to the document on ‘The Economic Context’. One sentence which Nick particularly objects to here is

“The crisis was precipitated by the excesses of global financial markets but has also exposed the chronic instability and grotesque inequalities which have characterised free-market globalising capitalism since the 1970s.”

According to Nick this fails to “specifically locate the present crisis as a crisis of the capitalist system as such”. It’s a curious reading of a paragraph which specifically refers to ‘capitalism’. It is true that the introduction, quite deliberately, does not provide a sufficient analysis of why capitalism is a system prone to crisis, and does not endorse the specific theoretical explanation of the recent crisis, which Nick himself advocates, as a crisis of profitability. Yet as he himself acknowledges in passing all such ‘fundamental cause’ type explanations have been vigorously contested in recent years and there is certainly no scientific consensus even among Marxists on such questions.

It follows that we should adamantly reject any suggestion that Left Unity as a political party should adopt a position on such questions. Not only is that unnecessary – since we can unite around the simple recognition that this is a crisis of capitalism in which once again the costs, in unemployment, real wage-cuts, intensification of workloads, and cuts in public services, are being imposed on the vast majority, whilst the 1% continue to rake in bonuses and avoid taxes. It would also take us down a dangerous path, the consequences of which are evident in the way in which, quite absurdly, arguments over these questions within far left groups have led to splits and expulsions. These are theoretical issues which need to be addressed in a spirit of open debate and scientific enquiry, and could never be resolved by voting at a political conference.

Nick Wrack, however, goes on to question the emphasis on financial markets in the document and suggests that it locates the crisis ‘in the financial sector’ alone. In fact the claim that the crisis of 2007-8 was ‘precipitated’ by the excesses of global financial markets is merely stating what even those Marxists, such as Michael Roberts, on whom Nick relies, would not deny. The word ‘precipitated’ was carefully chosen to indicate that there were underlying factors at work which the document does not specify – and, to repeat, does not need to specify. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, one meaning of the word precipitate is “to bring on quickly, suddenly or unexpectedly”. That was indeed what happened in the autumn of 2008 when the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the US based investment bank, suddenly led to a paralysis of global financial markets, and a potentially catastrophic meltdown process, only averted by massive intervention of states and central banks.

What Nick is trying to read into the document is a claim that quite simply isn’t there – the claim that somehow only the banks are the problem, or that simply reversing the decades of ‘neoliberal deregulation’ would suffice to resolve the contradictions of capitalism. Some in Left Unity may believe that, but I certainly don’t. What we should be able to agree on is that the processes of deregulation, privatisation and austerity implemented over the last 30 years have made things worse, both in terms of inequalities (the data are indisputable as the new book by Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century, has confirmed in overwhelming detail) and instability (simply compare the number of financial crises since the 1970s with their virtual absence in the years of regulated capitalism in the core of the system from 1945 until 1970). Nick however doesn’t want to accept the evidence for this out of fear that it could lead to ‘reformist conclusions’. That is scarcely the scientific approach advocated by Marx which always responded to the real course of history and never simply relied on an abstract theoretical schema as do so many of his latter-day followers (or epigones, to use a word Nick will no doubt recognise). I’ll come back to the question of ‘reformist conclusions’ below.

2. Can neo-liberalism be reversed?

The critique proceeds, however, to question whether ‘things would be improved if we went back to the post-war period, especially to the reforming period of the 1945 Labour Government’. The Policy Commission document doesn’t actually advocate a return to the policies of the 1945 Labour government (which, apart from the Bank of England, never even considered taking the banks or insurance companies into public ownership). Nevertheless Nick insinuates that such a ‘return’ is implied by our critique of ‘neoliberalism’, thereby conjuring up the dreaded spectre of a ‘regulated’ form of capitalism.

There is a noticeable ambivalence in the ISN position in this respect. On the one hand it recognises that in response to the crisis of 1976 Labour, followed by other social-democratic parties across the globe ‘abandoned their commitments to the welfare state, to adequate health care, decent pensions, and became almost indistinguishable from their right-wing overtly pro-capitalist opponents’. This surely implies that something significant did change, and for the worse as far as the mass of workers are concerned. It would then follow that a reversal of those changes, if it could be achieved, would constitute a significant gain for those workers, indeed for the vast majority of the population. So it seems they agree that ‘things would be improved if we went back to the post-war period’. Presumably they would also agree that the attempts at reform, however limited, by radical social-democratic governments in South America – Chavez in Venezuela, Morales in Bolivia, Correa in Ecuador – have ‘improved things’.

However, Nick Wrack in his critique proceeds to claim that any attempt to reverse 30 years of neo-liberalism in Britain is doomed to failure. This is a more serious argument. His claim that there were a series of specific conditions in the aftermath of 1945 and the end of the Second World War which enabled reforms is correct, although he is wrong to suggest that these were simply contingent on the postwar boom. Labour’s reforms after 1945, including both extensive nationalisations paid for by issuing government bonds and the introduction of the NHS, were pushed through at a time when the economy was still very weak, with a massive level of national debt and dependence upon loans from the USA to pay for essential imports. The postwar boom didn’t really begin until the Korean war in 1950 and its political fruits were then reaped by the Tories. What Labour did inherit from the war was a system of effective controls, over movements of capital and the financial system, which has long since been dismantled. That in turn, as the Policy Commission document explicitly states, makes any reforming government much more vulnerable to the threat of capital flight and investment strikes. That was certainly the experience of Labour in Britain after the 1974 election and the Mitterand government in France in the early 1980s.

Certainly social democratic governments have almost always capitulated to such pressures except, as in the South American cases mentioned above, where there has been a massive mobilisation of workers and the dispossessed as a countervailing force. We should be under no illusions, as I emphasised in my speech in Manchester presenting the document, about how the 1% in general, and the City of London financiers in particular, will react to a threat to their privilege and wealth.

That however does not entail that change is impossible or that significant benefits for ordinary people cannot be won short of the complete overthrow of capitalism as Nick implies.

A left reformist government could implement the measures outlined in the document. We could introduce simple measures from bringing energy companies back into public ownership to ending tax havens in the Channel Islands, from building new council houses to abolishing anti-trade union legislation. We could take the urgent measures necessary to reduce carbon emissions and develop renewable energy. Full employment with reduced working hours is possible under what would remain a ‘mixed economy’ but the nature of the mix would change radically over time. We would promote new forms of public ownership, cooperatives and other forms of community ownership, but we would not seek to take over every small business, or abolish the market overnight.

This would certainly not amount to a return to the ‘mixed economy’ of Britain on the 1950s and 1960s as Nick claims. It would be a transitional economy, with all the tensions and contradictions which are inevitable in any protracted transition from one type of social system to another. Yet for Nick and the ISN the very concept of the mixed economy is anathema, symbolic of a commitment to ‘managing capitalism’ which can only end in disaster. Yet his own alternative which seems to involve an elected government implementing a full socialist programme in its first term with the ‘backing’ of the mass of the working-class, ‘followed closely’ by other countries in Europe, is as speculative as any utopian scenario from the 19th century.

What the ISN misses is that the result of a left government introducing these measures would be to significantly increase the collective bargaining strength of those in work (one only has to look at the effect of the much more limited Roosevelt New Deal in the USA in the 1930s to get a sense of what could happen). It would deliver meaningful improvements around which it could mobilise a multitude to counter the resistance of international capital and its political agents. It certainly wouldn’t be easy – but it would be a radical challenge to the power and resources of both international capital operating in Britain and the tiny minority which currently dictates the terms of political debate accepted by all three main political parties. It would constitute a rupture with the politics of austerity, of further cuts in public spending, and acceptance of the legacy of neo-liberalism, currently accepted by all three major political parties (and by UKIP as well of course).

It is a programme which overlaps, of course, with the demands of the People’s Assembly but goes further, and around which we can campaign effectively and mobilise wide popular support. Polls show that. Without that mobilisation as Nick might well agree we will achieve nothing. Where we differ is what sort of strategy we need to get there. Must we insist as Nick does on winning support ‘patiently’ for a ‘thorough-going socialist programme’ as anything less than that peddles illusions in the possibility of reforms? Or do we focus on an alternative programme of radical or structural reform, on which we stand in elections with the aim of actually making a difference to the lives of the vast majority in the near future? That might appear like a fantasy anyway in the British political context – but we need to look at what’s happening elsewhere in Europe, especially with the growth of left parties in Greece, Portugal and Spain, parties whom Nick simply dismisses in one line as ‘reformist’.

A question of strategy

In my introduction to the document at the Manchester policy conference I referred to the Address Marx wrote for the First international in 1866. This was an Address which in its specific demands was certainly reformist and designed to hold together the diverse species of anarchists, trade union leaders and socialists who for a short period at least would unite around the principles of international solidarity for workers struggles across Europe. Its model for what could be achieved was the successful campaign for the 10-hour day in Britain. It included a whole section in support of the cooperative movement of the time. It combined a vision of the self-emancipation of the working-class with proposals which arose from the immediate situation of workers at that point in history. We need something comparable within the European Left Party today.

Nick is quite right to say that the Commission document offers a programme of partial reforms as the immediate task of a left government. But it also looks forward, offering an outline vision of a radically different society based on the principle of ‘from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs’. A government elected on this platform would be helping accelerate a process of transformation of society. It would certainly not constitute the end of that process, an end we cannot possibly foresee as it will depend upon the creativity of the multitude, not the utopian schemas of novelists, philosophers or even lawyers, however inspirational these may be on occasion. But to wait ‘many years’, as Nick argues will be necessary for ‘implementation of the socialist programme across Europe’, is, to the majority of those suffering from austerity today, a counsel of despair. The threats to the planet of environmental catastrophe are in any event simply too urgent for us not to pursue any measures which might avert disaster for future generations.

I welcome his agreement with our statement that we cannot abolish capitalism in one country, but his conclusion that nothing short of that is worth attempting does not follow. It is this contemporary version of what was termed ‘impossibilism’ in France around the end of the 19th century (when the wing of French socialism led by Guesde argued that any sustained improvement in wages or conditions was impossible under capitalism and even at one point argued against supporting universal state education as it would be used to promote bourgeois ideology) which constitutes the core of the ISN political position. Perhaps I need to insist that this is not to argue that the ‘possibilists’ of the time, who were notorious supporters of joining coalitions with bourgeois parties, were right either.

Nick may reply that towards the end of his critique he insists ‘the ruling-class can be forced through mass action to concede reforms that would require diverting resources from the wealthiest to the poorest’. So perhaps he is not a strict impossibilist after all, despite all the earlier comments about how it’s ‘utopian’ to argue for ‘partial reforms’. Yet rather oddly he sees no role at all for a left reformist government in this process, winning an election on the basis of mobilising and supporting mass action, despite the fact that this has become a critical question in Greece today with the growth in support for Syriza. Existing bourgeois parties can it seems be pressurised into concessions according to Nick (although numerous mass general strikes have failed to do that in Greece over the last three years) but left reformist governments will be able to offer nothing except betrayal or disappointment. It is this perspective, not the specifics of what’s in any of the policy commission documents, which is really the most fundamental source of disagreement within Left Unity today.

There are many armchair strategists on the left in Britain, and elsewhere, and none of them command a battalion, let alone a workers’ army capable of realising their speculative scenarios. In a Facebook discussion since the Manchester conference, Nick criticised me for simply counterposing a vision of a future society to the immediate struggle and argued that we need a roadmap of how to get from one to the other. The task of socialists it would appear is to imitate Moses – to lead the way to the promised land and hope that the masses will follow not too far behind, before the waters close in on us all. My response was that we cannot possibly have a roadmap for a future which is inherently uncertain and that the masses will have to construct the road itself in the course of struggling for a better world. I might also have added a comment (but didn’t want to make it seem personal) about the understandable scepticism of many people towards self-proclaimed leaders standing on street corners, as some have for many decades, each offering their competing programme as the one and only true roadmap (and I myself was one of those for many years). As Mike Marqusee said in his contribution to the platform debate last year, none of us can claim to have any certainty about the way forward to a different future, given what’s happened over recent decades. Or as a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Syriza, Aristides Baltas, put it in an interview in the 2013 Socialist Register:

“We didn’t present the view, let’s say, in the sense of a theory predisposing us to take power by an uprising or by a general strike or by I don’t know what. But we wanted to follow the movement as it developed. Hence we tried to participate in the movement and present our views so as to try to guide it while at the same time learning from it and following its objective rhythms. I think the phrase that would catch this idea is from Antonio Machado, the Spanish poet, who says: don’t ask what the road is; you make the road while you walk on it”

I would add that constructing our own road doesn’t guarantee that there are no detours or forced retreats, accompanied no doubt by many arguments and ruptures along the way. But the question of whether or not we should support Syriza forming a government which rejects austerity and the demands of the Troika (the EU, the European Central bank and the IMF, which have imposed conditions such as further cuts and privatisations for Greece to obtain more funds), admits to my mind of only one positive answer. Many will warn of the dangers, and Syriza will need to be bold, but their victory would still transform the political atmosphere not just in Greece but across the whole of the EU.

That said, we in Britain have a more immediate task which is to break out of the ghetto of the far left and to shift the balance of political debate ensuring that a left alternative to the politics of austerity gets a much wider hearing, as we have begun to do. That’s why we presented the Economic Policy proposals in that form – and that’s why I am willing as one of the elected principal speakers of Left Unity to stand on any public platform and defend them.

25 comments

25 responses to “In defence of the economic policy of Left Unity”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

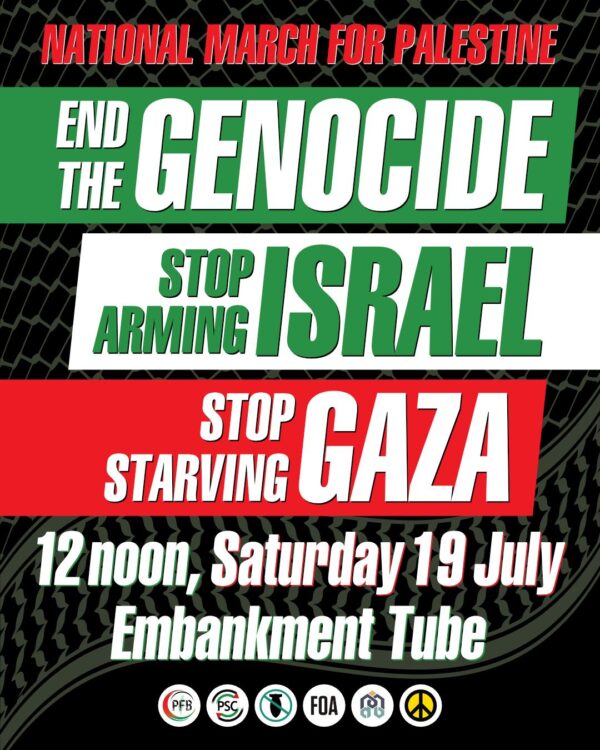

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

An excellent response to some of the Far Left criticisms of our recently adopted Left Unity Economic Strategy. The original critique, by Nick Wrack, can be found on the Independent Socialist Network Website, and was distributed at the Manchester LU Conference.

As Pete says, better to take innovative political risks , building a radical Left broad democratic socialist party of struggle, not expecting to be able to predict the outcomes by reference to revered doctrinal political texts , and try out new ways of organising the political and campaigning fightback against Austerity and capitalism generally, than be trapped forever in the inward looking Left bubble of endless doctrinal debate.

This is a side issue, but talking about reference to revered political texts Pete keeps on referencing the inaugural address of the First International as proof that Marx wanted a mixed or reformist programme . But the inaugural address was never intended to be a sweeping manifesto like announcement; instead people should read the Rules of the International to get a better idea of what they were trying to do

http://www.marxists.org/history/international/iwma/documents/1864/rules.htm

Great article, apart from the praise to Syriza, which, frankly, is a party which has exactly no credibility at all.

I mean, how can you possibly break out of austerity without getting rid of the euro first? What do you think would happen if you try that at a time like this when you’re 100% reliant on the Troika for your money supply?

“how can you possibly break out of austerity without getting rid of the euro first”

It is theoretically possible, at least in the short term. The Greek government doesn’t have the ability of a sovereign government to issue its own currency so it needs to get it from somewhere to keep its budget within a close balance.

If it removes money from general circulation in the form of higher income tax, higher VAT etc, and cuts spending in an attempt to stay within EU rules then the economy will spiral down, as it has, into a general depression.

So it has to find Euros from other sources. Euros that otherwise would not be spent in the economy. That is only possible by taxing the very wealthy. Syriza need to say , in effect, OK if we need to balance our budgets and the working classes haven’t got the money then we are going to do the only thing possible and impose high wealth taxes on the ruling class!

I’d be interested to see how the Troika would react to that!

That won’t work.

For starters, there’s a high probability that the very wealthy Greek have already moved most of their liquid assets abroad, which would make this srategy a moot point.

Second, imposing this level of taxation on the wealthy would invite retaliation on the bonds markets, further crippling the spending ability of the Greek state.

Third, even if you managed to somehow reflate the Greek economy via deficit spending (which would be quite a daunting task) while remaining in the EMU you would mainly be boosting imports, as the Greek industrial base is severely compromised and a recovery would result in higher inflation rates, which in a few years would hurt the REER with Germany and other more industrialized countries.

Then the Minskyan cycle would start all over again and in a few years you would be in the same place you are now but with a higher debt ratio.

I’d agree with you that it would be extremely difficult.

I’d just make the point that if enough Euros could be extracted from the very wealthy the reflation wouldn’t be “via deficit spending”. The books would balance.

I’m replying here because apparently it’s not possible to do so under you latest message.

Even if it was possible to impose extreme levels of taxation on the very wealthy (and it’s not) and somehow redistribute them to the less wealthy (via benefits, tax credits and the like), here’s what would happen:

1 – most of the extra money would be spent, not saved

2 – it would mostly be spent on foreign made goods (for the reasons I’ve mentioned before)

3 – this would lead to higher inflation, a higher current account deficit and therefore more foreign debt

4 – sooner or later the foreign debt bubble would pop (with bank defaults etc.) and Greece would be in the very same situation they were back in 2010

That wouldn’t solve any problem, it would just mean kicking the can a bit further.

This purports to be a response to my article in Bulletin No. 3 of the Independent Socialist Network. I hope that people do take the time to read what I argued in that article.

http://www.independentsocialistnetwork.org/wp-content/plugins/pdfjs-viewer-shortcode/web/viewer.php?file=http://www.independentsocialistnetwork.org/ISN_LUConf_Bulletin3_PRESS.pdf&download=true&print=false

Pete does not answer the points I raise but puts up some Aunt Sallies to knock down.

Nowhere in that article or in any other that I have written have I argued against a struggle for reforms. The class struggle is incessant and our class cannot afford any respite in fighting to protect its interests and to try to win concessions from the capitalist class. Pete’s assertion that I conclude “that nothing short of [the abolition of capitalism] is worth attempting” is based on nothing to be found in my article here or elsewhere.

My central thesis is pretty simple. The class struggle is ever present under capitalism. The ruling capitalist class exploits the working class for profit. The working class has to struggle every day to defend itself. Any socialist worth their salt participates in, supports, builds and encourages all working class struggles. But for socialists it is not enough to fight for the status quo or even improvements, welcome as they are. Socialists argue that we must also fight to get rid of the system that causes class struggle, that is, we must fight to get rid of the profits system – capitalism. Therefore, in the course of participating in the class struggle in all its forms socialists seek to explain the link between the class struggle within capitalism and the class struggle to end capitalism.

I don’t see anything ‘impossibilist’ in this.

My criticism of the Economics Policy document and much else that is argued in Left Unity is not about advocating reforms – which I support – but sowing illusions that reforms by themselves are enough.

Pete

I write as someone who broadly supports the Economic Policy Document (especially as amended at conference). I do feel it is invaluable to have a worked out, thoughtful, detailed document and set of demands around which support can be built, as opposed to a list of ulimatum demands in a brief “what we stand for” leaflet, that, as you say, can be shouted from any number of , often rival, street corners.

And yet….and yet. I still have some sense of trepidation regarding some of the political assumptions behind the document, which you have very usefully helped me to work out by writing your article, and I hope Nick Wrack won’t be too shocked at my offering him a partial defence.

The crucial issue, it seems to me (almost the only issue) is how we think this programme relates to the actual business of achieving a society of fairness, justice and economic democracy for all (aka socialism). In your answer to Nick, you answer the wrong points and dodge some of the real issues.

Of course it is ridiculous to have a policy on whether or not the crisis in capitalism is caused by the tendency of the rate of profit to decline. I have been in parties that tried to do that and it is unnecessary foolishness. But that is not the main issue. The real issue is whether the problem facing the majority of the population today is primarily the “neo-liberal” changes that have occurred since the 1970s, half way through the Labour government, or whether it is capitalism itself. Was Britain under Harold Wilson in the 1960s better than now? – Undoubtedly, but it was still capitalism – a rotten, unfair, undemocratic, exploitative and oppressive system.

So the question is – Can Left Unity (just imagine for a moment!!) be elected and run a kind of Harold Wilson, or Clem Attlee government, implementing major increases in the social wage, nationalising large sectors of private industry, and fleecing the rich in new tax increases without challenging the essential basis of capitalism ie the control of the economy by the rich and powerful interests? EVERY attempt to do that, even in 1945, or even in the new Latin American experiments, ends up with economic chaos caused by widespread sabotage, a collapse of the currency, flight of capital abroad, food shortages etc.

The Left Government is then faced with a clear choice. Either do what the capitalists want (cut wages, cut benefits, take on and defeat the more militant workers – look at Brazil now)or stand firm and take over the bulk of the economy and take on and defeat the rich and neutralise their economic and state power. Incidentally, this is does not at all imply nationalising everything, as Phil Hearse explains so well in his article on this website, but it DOES mean fundamentally breaking the stranglehold of the rich by seizing control over the main levers of economic and state power. Now, if you are going to do that, then you need to have prepared a mass of support, maybe years in advance, in every workplace and community which is ready to come to your practical, physical defence.

That is the difference, which you get really confused about, between using mass action to win concessions from a pro-capitalist government, and having a LEFT government trying to manage capitalism for an extended period. It is not just that the left government is not good ENOUGH, or a mere first step. Such a government can only manage capitalism effectively by actually ATTACKING workers, being complicit in the maintenance of the capitalist economic and social order and then being voted out by disillusioned and betrayed workers at the following election. All this was recognised decades ago by Miliband’s wonderful father, Ralph, in his works “Parliamentary Socialism” and “The State in Capitalist Society”.

You say your aspiration is for an end to capitalism, and that the party stands for this. I am sure of the former and know the latter, but that in itself does not matter unless that aspiration is reflected in all policies, short and long term. The Labour Party throughout the 20s and 30s had “socialism” (as defined by clause 4) as their aspiration but it was always “but not quite yet”. In the end, of course, it became “never”.

Now you, too, seem to be suggesting that it is possible “in the near future” to have a government that could rule for an extended period (maybe in successive alternating governments?)and implement our programme without necessarily breaking the economic and state control of the capitalists, who, presumably, would shrug their shoulders and defer to the democratic mandate of the people. Really?

In many discussions regarding the different platforms last year I was frequently assured by supporters of the Left Party Platform that this was not envisaged, but now I am a little concerned.

The Labour Party conference in 1970 voted for taking over the “commanding heights of the economy”. Of course, Labour would never have done that, but why is this demand not suitable for us today, given how capitalism has proved itself so much more obviously disgusting than it had done by the 1960s? Why can’t our economic policy contain the demand for nationalisation of all the most powerful, strategic companies that dominate the economy, rather than those recently nationalised plus the banks. This is not the same as standing on a street corner demanding insurrection or revolution, or even general strikes, but it does put the ENDING of capitalism on the agenda not just the management of an INHERENTLY unjust system.

Many perfectly valid points , Ray. I think concerns about the ability of a “broad church” left party like Left Unity – encompassing, reformist socialists, revolutionary socialists , and non socialist radical liberals of various sorts, to pursue , when in national or local governmental office, an uncompromising pro working class Left path in the teeth of massive capitalist resistance, are well founded. Certainly , as a claimed “sister party” Syriza is showing all the classic signs of caving in to the pressure of “the Market” in the form of The Troika, already – even before it gets into office.

So a broad based radical Left party with policies which though not obviously “revolutionary” actually would place us quickly at loggerheads with the power of the capitalist system very in the specific context of the world capitalist crisis and the neoliberal Austerity offensive, is riven with dangers going forward . Yep. Quite Right. Unfortunately NOBODY in the working class is listening to the tiny revolutionary socialist groups at all . The avowedly revolutionary socialist message is simply not on any mass agenda today.

The issue surely is just how long The UK and the broader European socio-political structures can continue “in the old ways” before the social tensions produced by the ever tightening Austerity screw causes all the old party structures to break apart – a la Greece over the last five years. If we on the Left don’t make every effort to start the mass mobilisation of at least the most “advanced” sections of the UK working class over the next few years – and that is only currently possible on a radical transformative, but in pure policy terms essentially “reformist” political programme of resistance, it is only the Far Right that will appear to be saying “radical anti establishment ” things against the status quo – because the full cream revolutionary socialist message is simply too far outside of current working class consciousness to get any sort of hearing at all .

I don’t think we have 20 odd years of leisurely party building ahead of us either in the UK or across Europe. The pace of social disintegration and fast changing political allegiances already well developed in Greece – but also evident in France , Spain, Italy, Portugal – often of a very worrying Far Right kind unfortunately, will continue apace as neoliberalism uses the Austerity con trick to destroy all the social welfare and wage and labour rights of the postwar period.

Left Unity was born out of a political and socioeconomic crisis – of which the huge leap rightwards of New Labour is just a small part. We will grow in a continuing period of crisis, and no doubt , probably sooner than most of us imagine, reach a political crossroads which will bring the reformist and revolutionary wings of our party into profound dispute. The job of revolutionaries is to be well embedded within Left Unity throughout its life, so that , unlike Syriza in recent months, our party continues to steer resolutely Left, rather than rightwards into compromise and ultimate betrayal.

OK John

but “compromise and ultimate betrayal” are unavoidable if we don’t even say now that we are not interested in running an Attlee/Wilson type Labour Government. If, at this stage, we don’t even theoretically allow for the possibility of an LU govt dealing a knock-out blow to the power of the ruling class (for want of a better word) in order to prevent them from derailing and crushing us, then we will not be able to ask for the necessary support from the bulk of ordinary working people to support their govt against the ruling class backlash.

The document does, at least, contain a clause allowing for the nationalisation of any company that tries to sabotage a left government. That provides a chink of light for the future. Thank God for Manchester’s amendment. But why not just come out and say that our policy is to take over the leading and/or strategic companies in each sector, to break the power of the ruling class to bend the government to its will. We all know it will have to come to that. Let’s just say so.

I’m not God (!) but the Manchester amendment was written and proposed in Manchester by me, but proposed to the conference by another member since I couldn’t attend. Specifically the nationalisation of “companies that attempt to destabilise a Left Unity government, by a ‘strike of capital’ or by trying to transfer assets overseas”.

Actually, I did propose an “e.g.” before the two ways I suggested such sabotage could take place, but that was amended at the branch meeting due to someone arguing that it would otherwise be too vague.

As someone who hasn’t spent a lot of time in left parties/splits and so on…

Three things.

It seems amazing, gobsmacking, to have a debate on “ending capitalism” and getting “rid of the profit system” when that system is – if we go back to the ancient Greeks – about 2,500 years old give or take. LU hasn’t even run for a single council seat yet. Can’t this wait? Getting “rid of the profit system” – what does that even mean?

The subject of “sowing illusions” via `reformism`.

Suppose Al Gore had defeated GW Bush, Rumsfeld, Gove, Cheney et al in their disputed US election. Do you think that `reformist` illusion would have meant many hundreds of thousands/a million plus Iraqis would still be alive today? Or not? Or is that an irrelevancy en route to demolishing “the class struggle.” When you `reform` a very big/powerful thing it can have very significant consequences for the lives of ordinary people.

My only advice to Pete – who put the time and effort into working this start document for LU – would be to leave ignored anyone who wants to live in a perfect leftist world. One inhabited only by themselves and the 35 other bods who read their International Worker Sparta Power Star Weekly or whatever it’s called.

LU can have its own economic ideas, without the dogma, and live or die by them, much needed reforms included.

Hi Coolfonz

I don’t think asking for the inclusion of a demand that was supported by the mainstream of the Labour Party 44 years ago is particularly extreme. I don’t recognise the cardboard leftie stereotype you portray, at least with regard to myself. After a Trot phase as a young man I took refuge in many years of disillusioned idleness via the Green Party and only now has LU inspired me to get back involved.

The fact remains that when you are in government, if you don’t break the power of the rich and powerful they will break you and force you into running their system essentially in their interests. Of course, they can tolerate reforms in the good years and we should fight for all of those we can. 1945 was allowed because capitalism was effectively bankrupt and the nationalisations saved vital infrastructure industries that would not otherwise have survived. The NHS and the welfare reforms were tolerated because all over Europe the threat of revolutions were terrifying the ruling classes, not to mention the fear of the Soviet Union’s military might.

Nonetheless, you cannot threaten their essential interests as rulers via the economy or the state without expecting massive reactionary resistance. If you don’t at least theoretically prepare for that you are lining us all up for a vicious and bloody defeat.

Coolfonz. You claim “the profit system” has existed for about 2,500 years” ! You need to bone up on your historical/political understanding just a tad, mate. “The profit system” we aim to replace with socialism means profit-driven modern capitalism – not just any old system of oppression and exploitation. The ancient Greeks, and the Roman Empire, Persian Empire, etc, had a slavery-based dominant “mode of production” – quite unlike modern capitalism – with a very different internal dynamic and range of social classes than exist today under bourgeois capitalism. It’s true that such societies used limited amounts of gold and silver based money for trading transactions – and that there were some limited “capitalistic” moneylending for interest based features in some aspects of the late Roman period. Nevertheless these societies were not in any way “capitalist” . Feudalism dominated Europe and many other areas of the world for centuries – until in Europe bourgeois capitalism burst out of it from the developing towns in the 17th century onwards – and slowly undermined the rigid class/caste based agricultural society Feudalism represented. Significant money use , and limited lending for interest, existed under Feudalism – but was not the key driver of the largely agricultural , peasant-based Feudal mode of production.

Modern Industrial Capitalism as a profit-driven globally spread system has only existed for about two hundred years or so – even then always intermixed with a wide range of pre capitalist semi feudal, even slavery-based features in many societies on the margins of the fully developed Western capitalist core economies. In fact it it is only in the last 20 years or so that the “working class ” of “free” wage labourers has actually outnumbered the pre-capitalist peasantry across the world ! The Globalisation and neoliberal ascendancy of the last 30 years represents the first time that capitalism has actually achieved the feature of a truly global mode of production

Left Unity is a socialist party, Coolfonz. Your many posts here and on other sites show clearly that you are not a socialist. That’s fine – Left Unity is a broad church – unity in action between socialists and non socialist radicals in fighting the Austerity Offensive is one of our aims. However our socialist objectives as a party was overwhelmingly decided at our founding Conference. That guides all our Party policies. There are plenty of books available to explain to you what capitalism is and what socialism is.

We do indeed need to throw away a lot of outdated leftie dogma – but the core of our socialist beliefs and theory remain perfectly sound. Without that philosophical and theoretical core Left Unity would be yet another capitalist party , making opportunist policy offers to the electorate whilst tacking to the pressures of the market place. Left Unity isn’t just aiming to manage and maintain a slightly reformed, “nicer” capitalism. We leave that futile objective to parties like the Greens

Ray G – I don’t disagree with anything you say. But “when you are in government” is some way off for LU I think.

John – if there was a rolleyes/face-palm icon available here I would have stuck it up instead of this sentence.

I’s suggest that Left Unity might want to look at the MMT economic school of thought. The big problem, as I see it isn’t traditional Toryism, but neo-liberalism which has infected nearly every political party including the Labour Party of course.

Ed Balls’ promise to produce a surplus is just absurd. The UK economy needs a good old fashioned Keynesian stimulus right now to get it going. A governement surplus equates to a non-government deficit. In other words, money will be drained from the economy in taxes and worsen the recession to a level as bad as we now see in Greece and Spain.

See for example: http://petermartin2001.wordpress.com/2014/03/31/the-economics-of-a-budget-surplus-something-to-think-about-before-making-rash-promises/

I agree about the MMT, if we are going to change things, we need to know what we are doing.

Peoples’ needs must be served, but we still must make use of science in our planning.

The main economic policy of LU should be to nationalise all industries that are related to maintaining a certain ‘standard of living’. This is the only way to fully control our destinies.

The most important industry is the ‘creation of money supply’ industry aka banking. By controlling this facet of the economy, you will hold the power to transform a country. However, I don’t this is possible without the cooperation and collaboration of other countries in an effort to reduce the control of the private banks. (However, there should be a discussion on the implications of doing this. Many times throughout history wars have been started for this very reason)

The other industries will thrive if money supply is controlled (because debt can be issued at 0% interest in government controlled interests)

Once you sort out the general direction of the economic policy, it needs to be conveyed to the public in a digestible manner i.e. do you want a home interest free? do you want affordable utilities with prices that only increase when the government needs to invest into cleaner renewable energy? do you want a higher level of education for your kids? do you want better opportunities? do you want better pay or work for less hours during the day for the same pay? etc etc

In regards to the issue of the people of this country not noticing the left, the above sets it out very simply. Every constituency needs to believe that this is possible because at first people will think this is impossible. That’s how badly they have become slaves to this skewed to the rich/powerful system.

Ultimately, LU requires two general policies for the party. Once set of policies that help people in the current situation (short term) and one set of policies that will improve people’s lives in the future (long term).

I mean, for goodness sake…There are so many issues where LU could sway the population. Just need some good leaders that can argue a point cleverly.

Good day.

Nationalising certain industries may be popular, trains for example, the post office.

But also why should the state pay subsidies to private companies without taking stakes? After around two years of operation after being switched to wood pellets the Drax power station will receive around £700mn/yr in subsidies.

The state should at least have a stake for that kind of reward.

I’ve just returned from a holiday in which I’ve deliberately not kept up with this debate. Having now skated through the interesting comments, two brief points:

1. Personally I agree with Daniele Gatti about Greece and the Euro – and would have supported the left position within Syriza on this question at their last conference. It could be argued that announcing a break with the Euro in advance would simply generate even more capital flight out of Greece than has taken place. Nevettheless itis clear that any break with the Troika demands would entail at the very least using a threat to leave the Euro at some point as a bargaining position – a threat which it would probably be necessary to implement.

2. On taking over firms etc and the debate between John and Ray, although I boaldy agree with John this all seems unhelpfully speculative to me – and ignores two critical factors. On the one hand what we are able to achieve will critically depend on the mobilisation of the masses and the issue of workers themselves seizing control of the productive apparatus. On the other we will be in a situation where what we can achieve will critically depend on what is happenign elsewhere in Europe and globally – an isolated national economy will be extremely vulnerable to sanctions etc and Britain’s reliance on trade for essential imports etc in turn entails we have to export, do deals etc with further implicatiosn ( as under the New Economic Policy in the USSR in the 1920s) So my fudnamental response is yes we want to break the power of capital but that won’t happen in the course of a single rupture within one country. In the meantime lets be open to all sorts of possibilities around using control of finance to support and promote an alternative participatory economy of cooperatives etc The perspectives of Nick and those with similar ideas such as the Socialist party seem to me far too statist and ‘top-down’ in this respect – with far too little emphasis on the potential unleashing of the creativity of the masses..

Hi Pete,

capital flight during a currency swap can easily be avoided, as numerous past examples show. Here’s a nice writeup on the subject:

http://www.policyexchange.org.uk/images/WolfsonPrize/wep%20shortlist%20essay%20-%20jonathan%20tepper.pdf

It all boils down to two general principles:

1 – you DO NOT announce the swap in advance, that’s just asking for trouble. You just make secret preparations ahead of a weekend or a bank holiday and you do it all by decree while banks and stock markets are closed. After all, when Britain and Italy got out of the ERM in 1992 nobody announced anything in advance, it all happened very suddenly in both cases (and of course the two governments were swearing they would defend the exchange rate until the last minute). The UK announced exit at night, Italy on a Sunday (and they even called it a “temporary measure”, while everyone knew it would be permanent).

2 – In the meantime, you impose capital controls on cross-border transfers. After all, it is technically possible and Cyprus has been doing it for over a year now.

Pete –

Yes, of course any attempt to break the power of the rich over the economy will rely on the strength of mobilised ordinary people, but we can’t just suddenly issue a call to arms when we are in a crisis that anyone could see coming.

We have to do patient work NOW to prepare for that self-mobilisation, and suggesting that we can nationalise a few industries and raise taxes on the rich but otherwise run the capitalist system without attacking our own supporters is actively MISLEADING our potential future supporters, and fooling them into thinking that they can just vote for us and everything will be well.

Again, I have to say – if the demand for nationalising the “commanding heights” was OK for Tony Benn in 1970, how has it become ultra-left now??

Once again, Pete Green fails to deal with any of the arguments I made in the article he purports to be responding to and, for good measure, introduces another straw man – my supposed ‘statism’, whatever that means. Another lazy brush stroke. I would like to hear from Pete how he envisages us achieving socialism because the ideas he is defending won’t get us there.

Great article on the Guardian about the need for an Eurosceptic Left: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/may/07/left-progressive-euroscepticism-eu-ills