Dave Renton explores the political writing of David Widgery

David Widgery was a political writer. He devoted his life to communicating the ideas of Marxism, that society could be organised from below, and that workers could run the world. In his writing, he explained, he challenged, and he persuaded. His articles described the relationship between things, the connection between unemployment and racism, the link between crisis and capitalism, raising in Lenin’s phrase ‘many ideas’, so that the world could be understood as a single whole.

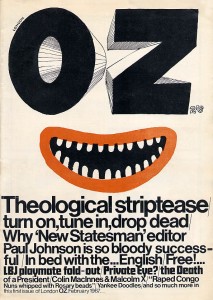

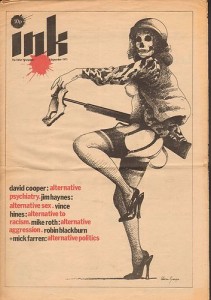

Some of the breadth of his work can be seen in the range of the papers and magazines that he wrote for. His own anthology of his work, compiled in 1989 includes articles published in City Limits, Gay Left, INK, International Socialism, London Review of Books, Nation Review, New Internationalist, New Socialist, New Society, New Statesman, Oz, Radical America, Rank and File Teacher, Socialist Worker, Socialist Review, Street Life, Temporary Hoarding, Time Out and The Wire. Any complete list would also have to include his student journalism, articles he wrote for Ink, and regular columns in the British Medical Journal and the Guardian in the 1980s.

Not that David Widgery was ‘only’ a political writer. He was also an activist, a doctor and an author. He attended the Ruskin women’s liberation conference, and edited the magazine, Oz, after its main editors were tried for indecency in 1971. He chaired the Campaign to Save Bethnal Green Hospital, and compiled three radical anthologies. He was one of the most active supporters of the History Workshop movement, and also helped to re-found the Hackney Literary and Philosophical Society. Widgery was among the first of his generation to grasp the significance of the women’s liberation and gay rights struggles of the 1970s.

He was also an incurable fighter, and a member of the Socialist Workers Party, as Paul Foot records: ‘David was a restless man. He was always driving his body further than it could go in feverish pursuit of something unattainable. He was quite unlike the popular image of a revolutionary. He was the opposite of David Spart or Citizen Smith. He was not one for party exclusivity. Most of his friends were outside the party. If he disagreed with the party, he said so. Indeed, so terrified was he of the image of the party hack that he would often say he disagreed when he didn’t.’ Juliet Ash, Widgery’s partner, also remembers Widgery’s restlessness. She recalls that he was always doing five things at once. ‘He packed all his life in, when he was a doctor and on call, he would be writing a book. He packed more into 45 years than most people manage in 70.’

In his obituary, Bob Light described Widgery as ‘A radical humanist intellectual on permanent loan to revolutionary socialism’. Like Paul Foot, Light pointed to the tensions between Widgery and the Socialist Workers Party he belonged to: ‘We need, we will always need comrades like Widgery and [Peter] Sedgwick to remind us that socialism starts and finishes with human beings and their needs. We need to be reminded that there is a world outside industrial sales and contact visiting. But what Dave only fitfully understood was that without the humdrum work of organisation and routine, the world will be condemned to stay a shithole for ever.’ Ian Birchall, who sparred with Widgery over his history of Rock Against Racism, Beating Time (1986), admires Widgery’s writing, but suggests there was a flightiness to his politics, ‘I knew David Widgery right back from ’68. A man of enormous talent, wonderful speaker, wonderful writer, but a man who was moving so quickly that he never bothered to correct his mistakes. All his books are brilliant, and they’re all riddled with inaccuracies. If you write like that, in his sort of way, then checking the spelling of the Leighton Buzzards isn’t the most important thing.’ I asked Ian, how might Widgery have responded to this charge? ‘He called me the sniffer dog of orthodox Trotskyism’.

To Be Young Was Very Heaven

Born in 1947, Widgery was a victim of the 1956 polio epidemic, and spent five years in reconstructive operations, graduating as he described, ‘from wheelchair and callipers to my first pair of shop-bought shoes’. It was a horrific experience for a young child to go through, trapped in a hospital ward without his parents and with the other children ‘crying, as I so clearly remember, ourselves to sleep at night with our nurses in tears at their inability to comfort us’. The experience did have one valuable result: it gave Widgery his love of the NHS, and may later have contributed to his decision to become a GP. Having survived this ordeal, Widgery was then packed off to grammar school, where he became quickly contemptuous of its rituals, ‘My school even invented a Latin song we sang about the school’s airy position above the railway sidings, which we sang like so many housewives being introduced to Royalty.’ He joined CND and took part in the Aldermaston march, and also wrote for the national school students’ U Magazine. At the age of fifteen, he read Jack Kerouac’s great novel, On the Road, and discovered in it ‘a coded message of discontent’. Later he would claim that Neal Cassady, the hero of the novel, was the ‘Leon Trotsky of his time’. David Widgery bunked off after hours from school to listen to jazz bands at the Rikki-Tik club in Windsor. He was expelled from his grammar school, appropriately enough, for publishing an unauthorised magazine, Rupture. In 1965, he interviewed Alan Ginsberg for Sixth Form Opinion, and was seduced by him, before escaping on his Lambretta. Later that year, Widgery spent four months travelling across the United States. He arrived as Watts, the black district of Los Angeles, exploded in riots. Widgery then journeyed to Cuba and later to the West Coast, taking part in anti-Vietnam protests called by members of Students for a Democratic Society.

‘David was a creature of 1968. All his life he remained fascinated by the political events of that wonderful year.’ Widgery came of age in the middle of the 1960s, surrounded by sex, dope and psychedelia, yet he was suitably cynical about his generation’s myths of cultural revolt, ‘All you need is love, but a private income and the sort of parents who would have a Chinese smoking jacket in the attic help’. ‘Against Grown-Up Power’, an article he wrote in 1967, spurned the values of the older generation, publicly attaching its author to the spirit of anger and revolt, that would manifested itself in the student protests of the following year’s events:

Yours is the generation which calls concentration camps ‘strategic hamlets’ and supporting the oil sheiks ‘a peacekeeping role’. ‘Democratic breakthroughs’ are things like letting workers at Fairfields actually talk to their boss or stopping students standing up when lecturers enter the room… Politics becomes the business of managing a given industrial system to reward those it exploits at intervals which more or less coincide with elections. The bad joke at Westminster represents the people, and together with the TUC, the CBI and the bankers becomes something called ‘The National Interest’.

Because Widgery was a hippie even before he was a red, he found his place among the underground papers that sprang up to celebrate and

spread their vision of the sixties. Richard Neville, the future editor of Oz, describes meeting Widgery regularly in 1967, and planning a new magazine with him. Widgery went on to write for Oz 1. The two men were good friends, although they often disagreed. According to one story, Neville met Widgery by chance at the Isle of Wight festival in August 1969. David apparently ‘had weaselled his way there as a Trotskyite rep of the electricians’ union’. They exchanged pleasantries, with Neville expressing surprise that a busy revolutionary could find the time to hear Bob Dylan. ‘If one per cent of this celestial crowd devoted itself to throwing yoghurt bombs at the Queen or undressing in court’, Widgery replied, ‘we’d all be a lot better off’. Neville and Widgery remained on good terms, and close enough for Widgery to pose as Neville on a Saturday night episode of the Frost Report.

Although he had been a member of the Communist Party and then the ultra-orthodox Trotskyist organisation, the Socialist Labour League in the early 1960s, it was only in 1968 that David Widgery decisively attached himself to the revolutionary left, by joining the International Socialists (IS), the fore-runners of today’s Socialist Workers Party (SWP). He was to remain a member of the IS and then the SWP for the rest of his life. Widgery was not the only young radical to become a socialist in 1968. Thousands moved to the left under the impact of the Tet offensive, when Vietnamese forces scored extraordinary victories against the greater military forces of the Unites States, under the influence of the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia in August, and the student protests and the general strike which broke out in France in May ’68. Widgery himself describes walking round London, ‘with a transistor radio in my ear to catch the latest news’. In Mexico, five thousand troops fired on demonstrators, killing over one hundred people, while in Germany, a generation of young activists moved were won to the tactic of immediate, violent action against the state. The nearest that English students could come to events in France and Washington was at the London School of Economics, where David Widgery bunked medical school and happily joined in the protests, which culminated in January 1969 when hundreds of students and local building workers tore down steel gates installed to prevent them from occupying the university buildings. These were certainly exciting times, and the membership the IS rose from 200 at the start of 1968, to around 1000 at the end.

In one of his books, Widgery made the gentle joke that he joined the IS because they were the only socialist organisation to publish a

decent obituary of André Breton. If this answers why he joined, then we also need to ask why he remained. Part of the answer is that the IS was the one organisation on the far left which was serious about building revolutionary politics within the working class. Paul Foot describes meeting Widgery for the first time, at York in 1968, ‘His eyes were shining and he had a grin on his face as though it were fixed there forever. I was off to speak on socialism at York University – he had just come from there. ‘It’s great’, he said. ‘Great. An enormous middle-class fun palace.’ Suddenly his expression changed, and he glowered at me. ‘They don’t need you there’, he said. ‘Not another of us. They need the proletariat.’ Foot remembered Widgery’s burning desire to see ordinary people running the world, and used this to explain how it was that Widgery could remain a socialist, while so many others of the 1968 generation became cynical and were ground down: ‘David Widgery believed above all else in the struggle for socialism. He knew for certain that individuals can’t get socialism on their own, and he committed himself all his life to the organisation which, he believed, tried hardest to adopt and raise its theory of socialism to the level of doing something to get it.’ Widgery was also attracted to the open spirit of discussion and debate within the party. Inside the IS, David Widgery found a hero in Peter Sedgwick, a member of the 1956 generation, famous today for his book Psycho Politics, and for having popularised the works of the dissident former Bolshevik, Victor Serge. Widgery’s account makes clear the immense emotional debt he owned to his hero:

Almost uniquely among the many Marxist intellectuals of the 1956 vintage, he didn’t just write about the left but made it, shaped it and served it as an active member of first the ‘Socialist Review’ group, then the International Socialists, and until the mid-1970s the SWP… Sedgwick’s politics were of Bolshevism at its most libertarian and Marxism at its most warmhearted and witty. He also dressed like a Basque beatnik, wrote footnotes on his own footnotes, collected tins of mulligatwany and was founding editor of Red Wank: Journal of Rank and File Masturbation, whose second (and unpublished) issue was to feature ‘Great autoerotic revolutionary acts’ and ‘Coming out as a worker: problems in a TU Branch’.

Underground Overground Left

Widgery’s role within Oz was to act as the conscience of the magazine, denouncing Private Eye and the Sunday broadsheets, mourning the loss of Jack Kerouac, and describing what might happen, ‘When Harrods Was Looted’. This article appeared in violet, printed on green, beside a complicated diagram presenting William Morris’s affinity with Rosa Luxemburg, and inside a front cover made of detachable day-glo stickers. The presentation was typical of the graphic eclecticism of Oz, while Widgery’s article was an earnest attempt to translate the concerns of classical Marxism into the language of the underground left, ‘Without these roots into and connections with working class life, the most scintillating critique of bourgeois ideology, the fullest of blueprints for student power, and the grooviest of anti-universities could all be paid for by the Arts Council for all the danger they present. To wait for revolution by Mao or Che or comprehensive schools or BBC2 is to play the violin while the Titanic goes down, for if socialists don’t take their theory back into the working class there are others who will.’

Widgery also reminded Oz writers that if the magazine’s language of ‘free love’ was to have any real meaning then it must take into account the sexism which was a definite part of the male hippie dream. Here he was deeply influenced by his close friend Sheila Rowbotham, one of the leading voices of the new movement for Women’s Liberation, who was briefly a member of IS and helped to organise the famous Ruskin Conference, which took place in Oxford in February 1970. Reviewing Richard Neville’s book, Playpower for Oz that year, David Widgery demonstrated that Neville’s vision of sexual freedom for men meant that he was in reality a ‘raving reactionary’ towards women. Neville, he pointed out, had not learned even the ABC of feminism: ‘Women are doubly enslaved, both as people under capitalism and women by men. The hippie chick has always been one of the most unfree of women; assigned to be ethereal and knowing about Tarot and the moon’s phases but busy at cooking, answering the phone and rolling her master’s joints.’

In the spring of 1971, Widgery acted as a Mackenzie’s friend for Neville when Oz came on trial, and defended the magazine to the best of his abilities, until Neville insisted on replacing him, as Widgery’s final medical exams drew near. Writing for Socialist Worker during the trial, under the pseudonym of ‘Gerry Dawson’, David Widgery made it clear that he had his own vision of rebellion, which went beyond the narrow masculine sexual radicalism which Oz championed. He expressed his reservations with Neville’s project, but went on to defend it, as one expression of a greater desire for revolutionary change, ‘There is a sort of erotic reformism which suggests that quite literally ‘all you

need is love’. It’s attractiveness is as considerable as its ineffectuality. But in reacting against it, socialist puritans are in danger of ignoring one of the most intimate of capitalism’s contradictions. Engels was right when he pointed out “that with every great revolutionary movement, the question of free love comes to the foreground”.’ Widgery was invited to edit Oz after the trial, as an exhausted Neville took a break. The magazine now was in decline, undercut by the growth of the left press, and unsure where to turn. Unwilling to reproduce its earlier staple photographs of glamorous under-dressed hippie women, the magazine had less and less to say, and eventually folded in 1972. Widgery penned OZ’s obituary: ‘Whether OZ is dead, of suicide or sexual excess, or whether OZ is alive and operating under a series of new names is unclear at the moment. What is clear is that OZ bizarrely and for a short period expressed the energy of a lot of us. We regret his passing.’

In Defence Of The Proletariat

Leaving Oz as the magazine slowly died, David Widgery became more active elsewhere as a journalist. He increasingly felt that the underground press had failed. As he told Time Out in 1973, the hippie papers had not succeeded in pushing their cultural radicalism into the hearts and minds of the working-class. ‘At the core of the shabby myths and collective dishonesties of the underground was the belief that the class struggle had had it, that the workers had been hopelessly bribed, bamboozled and betrayed.’ Yet the Bohemian milieu was impotent to change society on its own, and because of its indifference to workers, it was unable to win over the one force that could transform society. Thus the underground had become an empty vessel, incapable of turning its fine words into revolutionary actions. Widgery was to return to this theme in a later interview:

Occasionally, you’d meet shop stewards at conferences who were interested in the underground press, or got stoned, or were interested in radical music. That was always very fruitful. Otherwise there wasn’t much apparent link between the workers’ struggle and this psychedelic flowering. The former was pragmatic and fairly empirical, predominantly concerned with money and making excuses for Harold Wilson. The latter was almost wholly an imported problem, which is what made the ‘off with the pigs’ rhetoric so flimsy.

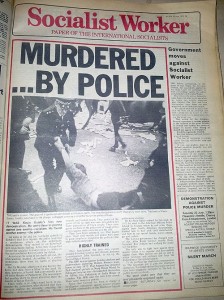

Widgery began to write more regularly for Socialist Worker. Paul Foot was then the editor of the paper, and vividly recalls working with him. Other writers were more reliable, but none of the paper’s many talented journalists, neither Roger Protz nor Laurie Flynn, could write as powerfully as David Widgery: ‘At times, lying in bed at night with the SW pages rolling around in the darkness, I would yearn for some plain good prose, something which people would enjoy reading for its own sake, even if the line was slightly dubious. There were so few who wrote like that: Peter Sedgwick did, so did Eamon McCann; and so, always, did David Widgery.’

Widgery and Orwell

I have described David Widgery’s early activism in some detail, because it is important to understand where his voice as a writer came from. Influenced by his love of beat poetry and Jazz, and also by own his active involvement in the underground press, David Widgery was a remarkably open writer, ready to borrow different from different styles and forms, and determined to put his message across in the most persuasive way possible. He understood better than anyone else of his generation that language is for expressing and not for concealing or hiding thought. Widgery consciously read and copied the popular writers of the past. Like George Orwell, Widgery loved Jonathan Swift, but his influences were many. Preserving Disorder includes articles on the political writers Fernando Claudin, Sylvia Pankhurst, C. L. R. James and Lenin, as well as pieces on Widgery’s other influences, Norman Mailer, John Lennon, Jack Kerouac, Bessie Smith and Billie Holliday.

In a famous essay, ‘Politics and the English Language’, George Orwell attempted to map out the rules of effective political writing. Most of the advice he came up with is still useful, but the point of the essay was to criticise the hack political writing of the 1930s and 1940s, and consequently, most of his suggestions were negative. Propagandists should not lapse into dogma, neither should they parrot any party line. They should also avoid tired or dying metaphors and also lazy clauses, ‘verbal false limbs’. Orwell thought that six rules in particular would cover most of the traps into which bad political writing then fell:

1. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If its possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use a passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word where you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules rather than say anything outright barbarous.

Like Orwell, Widgery wrote in a style that treasured originality and creativity. He was aware that communication took place through the readers’ imagination and not just through passive acceptance of the printed word. His writing style played with sounds and images to create meaning. It was a very simple, musical language. Indeed, if positive rules could be taken from Widgery’s writing to counterpoise to Orwell’s negative laws, they would include at least the following two broad statements of advice. The first rule would be always write for your audience. David Widgery wanted many people to understand him, and was not afraid to experiment. He used visual metaphors, experimented with grammar, and wrote in a language which copied the rhythms of speech. Any of these techniques he employed, provided they made his meaning easier to understand. One passage from an article he wrote for the magazine New Socialist in 1981 sums up David Widgery’s insistence that propaganda had to be relevant, or it had no value at all, ‘If socialism is transmitted in a deliberately doleful, pre-electronic idiom, if its emotional appeal is to working class sacrifice and middle class guilt, and if its dominant medium is the printed word and the public procession, it will simply bounce off people who have grown up this side of the 1960s watershed. And barely leave a dent behind.’ The second rule would be don’t just write for your audience – challenge them. Widgery’s writing asked his readers questions. He did not lecture, but involved his audience in a process of questioning. He prompted them to see for themselves the connections between different events. Writing about the death of Steve Biko, in the Rock Against Racism magazine, Temporary Hoardings, Widgery began with the events of the Soweto uprising, and proceeded to describe in detail the repressive apparatus of the South African state. Only then did he turn his readers’ gaze to the role played by their own Labour administration, ‘The British government voted in the United Nations, yet again, against business sanctions contra South Africa… Britain is still South Africa’s largest trading partner and investor. Almost a quarter of South Africa’s exports go to Britain and 4 per cent of British exports are destined for South Africa… The state that killed Steve Biko is, despite the diplomatic talk, deeply connected to Britain. To help black Africa to freedom, we will have to free ourselves.’

There are other ways in which a comparison with George Orwell finds in David Widgery’s favour. Cut off from any large political movement, Orwell returned from Spain a revolutionary, but became isolated and fell into cynicism. After 1945, the majority of his political contacts were moving to the right, and Orwell was unable to maintain a consistently left-wing anti-Stalinism. Demoralised, he allied with right-wingers, and failed when he sought to justify his remote position: ‘In our time it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing. Where it is not true, it will generally be found that the writer is some kind of rebel, expressing his own private opinions, and not a ‘party line’. Orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style.’ Unlike Orwell, Widgery was no maverick. Everything he wrote was the collective property of his family and friends. Juliet Ash describes Widgery showing articles to her, and also to her children as well, ‘Every time he wrote anything, he would test it out. Even when my daughter was young, 6 or 7, he would test things out on her. I remember him testing articles on me, and on my son. He had a way of talking that teased things out of people. He used humour, and made people laugh. He never left anyone out.’ Beyond his immediate acquaintances, Widgery also benefited from close contact with movements of protest, and with the SWP. Linked to a political party, but free to think within it, Widgery was as good a writer as Orwell, and a far more successful activist.

Like any political writer of any quality, Widgery in his enthusiasm would sometimes push an argument too far, as when he maintained that the left relied too heavily on newspapers and books. Written in 1973, the introduction to his book, The Left in Britain, regretted committing the memories of real people to the sole care of books and dusty paper:

In fact, because such a small group of people actually find written words convincing I half wish that it wasn’t a book at all but some species of talking poster which might express what the modern socialist movement feels like from within – its humour and music and oratory and colours and the intellectual sensations of its mentors and inventors, the autumn and granite of E. P. Thompson, the whiskey and ice of Alasdair Macintye or the hurdy gurdy of Tony Cliff.

I think the musical quality of this passage disproves its own argument. Widgery’s idea of a talking book-poster plays on the reader’s imagination and lasts with them. It is a forceful image, and less powerful for being expressed through the medium of the written word.

Doing Time

The period of the 1974-9 Labour government was a time of decay and cynicism, during which society shifted to the right, preparing the ground for the Tories’ election victory in 1979. Although it was elected with a left-wing manifesto and significant support, following the mass strikes of 1972-4, in power Labour was a massive disappointment. The government squeezed wages and cut public spending while also bringing the trade union leaderships into close contact with the government. Bitter struggles continued through the five years of Labour rule, but the overall result was to reduce the levels of militancy within society. The number of strikes fell rapidly, while the government held the line on its compulsory incomes policy. The International Socialists were riven by a bitter faction fight, and there was no mass movement to which its members could relate. Between 1974 and 1976, David Widgery published an anthology, The Left in Britain (1976), and started work on Health in Danger (1979). He also threw himself with enthusiasm into his new job, as an East End GP. In retrospect, however, it seems clear that Widgery was marking time, easing off before a future burst of activity. Paul Foot describes these difficult years well, and their effect on Widgery, ‘David hated orthodoxy. As the SWP turned for survival to its own orthodoxy in the long years of the “downturn”, David became restless. He ventured outside the party walls, returning often to lecture us at Skegness on the campaign against abortion in the 1930s or the gay liberation movement in the 1970s. “You’ve got to listen to those gays”, he told us in 1977.’ Although the mid-1970s were quieter for Widgery than the previous decade had been, it was not long before there was a mass movement, and his ideas could once more be put to the test.

Rock Against Racism

Before examining Widgery’s role in the anti-racist movement of the late 1970s, it is worth saying something about why such a movement was needed. The party which gained most from the failure of the Labour government was the National Front. First set up in 1967 as an alliance of different racist organisations, the NF only took off under Labour. In 1976, the NF received 15,340 votes in Leicester. The following year, it achieved 19 per cent of the vote in Hackney South and Bethnal Green, and 200,000 votes nationally. The real strength of the organisation was on the streets. According to Ken Leech, then working as a priest in London’s East End, ‘Between 1976-8 there was a marked increase in racist graffiti, particularly NF symbols, all over Tower Hamlets, and in the presence both of NF “heavies” and clusters of alienated young people at key fascist locations, especially in Bethnal Green.’ By 1976 and 1977, the NF had more activist members than ever before. Its cadres waged a violent race war, and thirty-one black people were killed in racist murders in Britain between 1976 and

1981.

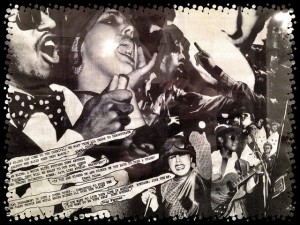

The National Front attempted to build in various milieu, among football supporters and the young unemployed. In the music scene, these were the years of punk, when the stadium bands of the early 1970s lost touch with their audience, and a new music sprang up, libertarian and anarchistic, in the best sense of these words. Caroline Coon described the anger of punk music at its birth, ‘The musicians and their audience reflect each other’s street cheap ripped-apart, pinned-together style of dress… The kids are arrogant, aggressive, rebellious… Punk rock sounds simple and callow. It’s meant to. The equipment is minimal, usually cheap. It’s played faster than the speed of light… There are no solos. No indulgent improvisations… Participation is the operative word.’ The NF attempted to tap into this new punk style. Here it was helped by traces of ambiguity which punk displayed towards fascism. The style was anarchistic, but politically vague and extremely individualistic. The sound of punk, with its jagged three-chord repetitions, was the antithesis of 70s reggae or dub, in Jon Savage’s phrase, ‘the style had bled Rock dry of all black influences.’ Members of the Sex Pistols and their entourage wore swastikas, as if the symbol could be a fashion statement, while one of the band’s last singles pronounced that ‘Belsen Was A Gas’, and the Jam’s first album cover featured a huge Union Jack.

With the NF in the ascendant, several well-known figures expressed themselves openly in favour of its racist message. In August 1976, Eric Clapton interrupted a Birmingham concert to make a speech supporting Enoch Powell, the racist Tory MP. This speech led directly to the formation of Rock Against Racism (RAR), and David Widgery was one of the leading lights in this new anti-racist movement. Two former mods, Red Saunders and Roger Huddle, wrote a reply, which was subsequently published in the New Musical Express, Melody Maker, Sounds and Socialist Worker, ‘When we read about Eric Clapton’s Birmingham concert when he urged support for Enoch Powell, we nearly puked. Come on Eric… Own up. Half your music is black. You’re rock music’s biggest colonist… We want to organise a rank and file movement against the racist poison music. We urge support for Rock Against Racism. P. S. Who shot the Sheriff Eric? It sure as hell wasn’t you!’ The letter set the tone of the new organisation. RAR published its own paper, Temporary Hoardings, and artists, musicians and writers participated in the creation of a musical and literary style, which drew its influence from French surrealism, Marxist politics and the best of punk. The message was angry, exciting and compelling, educational without sermonising, effective at reaching the young. David Widgery’s editorial in the first issue of Temporary Hoardings was RAR’s first manifesto, ‘We want Rebel music, street music. Music that breaks down people’s fear of one another. Crisis music. Now music. Music that knows who the real enemy is. Rock against Racism. Love Music Hate Racism.’

Part of RAR’s political radicalism lay in its total acceptance of punk’s rough working-class sound, the music of bands like the UK Subs, Ian Drury or Jimmy Pursey’s Sham 69. Sham 69 epitomised the RAR sound. Songs like ‘I Don’t Wanna’ and ‘The Cockney Kids Are Innocent’ were written for an audience of aggressive, angry, often unemployed young workers, precisely the people that the NF and RAR were both fighting for. In 1977 and 1978 Sham 69 gigs at Kingston, the London School of Economics, Middlesex Poly and their set at the Reading Festival all ended in mass brawls. At Middlesex Poly, members of the National Front stormed in through the lift shafts and briefly took the stage, but were repulsed, and the gig ended with Jimmy Pursey singing alongside Misty. In this way, the night ended on a note of real hope, as Syd Shelton recalls, ‘There was an affinity, a wonderful moment of black and white unity’.

By adopting this street music as it own, RAR took it out of the hands of the racists. Yet Rock Against Racism did not simply adapt itself to the existing punk sound. Rather it sought to change and develop punk music. For this reason, RAR brought together white punks and black reggae acts, Jimmy Pursey with rasta group Misty, Tom Robinson with Steel Pulse. As Rock Against Racism developed, so did the sound of the main RAR bands. The Clash, brought out a single, ‘Police And Thieves’, based on a Jamaican tune which was said to have blared out over the anti-racist riot in Lewisham. They also hired a black producer, Lee Perry, and wrote perhaps their greatest song, ‘White Man in Hammersmith Palais’. The Ruts also tried to fuse reggae and punk styles, while Siouxse and the Banshees, having worn swastikas in 1976 and 1977, now wrote ‘Metal Postcard’, based on the collages of the German anti-fascist Johnny Heartfield. Widgery, with his love of Jimmy Hendrix, reggae and the blues, was an important figure arguing for two-tone music.

Meanwhile, street conflicts between fascists and anti-fascists continued, reaching an early crescendo on 13 August 1977, when thousands of anti-fascists, including large numbers of local black youths, prevented the NF from marching through Lewisham. The original National Front demonstration was publicised as an anti-mugging march, a crude attempt to intimidate the many Afro-Caribbean residents in the area. Two counter-marches gathered in protest. The first was a coalition consisting of Communist Party members, Catholic organisations, local councillors and members of the Campaign Against Racism and Fascism. It expressed its opposition to the NF march, and then quickly left the scene: ‘The official protest march, including the Catholics, the councillors and the Communists, made indignant speeches against fascism in Lewisham and carefully avoided going within two miles of the fascists who were assembling behind the British Rail station at New Cross where the atmosphere was less forgiving. David Widgery’s Beating Time, takes up the story of what happened to the second march:

An officer with a megaphone read an order to disperse. No-one did; seconds later the police cavalry cantered into sight and sheered through the front row of protesters. So, without the organisation, it might have ended. Except that people refused to melt away from the police horses and jeer ineffectually from the sidelines. A horse went over, then another, and the Front were led forward so fast that they were quickly struggling. Then suddenly the sky darkened (as they say in Latin poetry), only this time with clods, rocks, lumps of wood, planks and bricks… The NF march was broken in two, their banners seized and burnt; only thanks to considerable police assistance was a re-formed, heavily protected and cowed rump eventually able to continue on its route to Lewisham… The mood was absolutely euphoric. Not only because of the sense of achievement – they didn’t pass, not with any dignity anyway, and the police completely lost the absolute control [they] had boasted about – but also because, at last, we were all in it together.

After several hours of street fighting between the anti-fascists and the police, one thing was clear, the National Front had failed to pass.

The effect of Lewisham was to give a massive boost to anti-racists. As messages of support and donations flooded into the SWP headquarters, the party decided to set up a full anti-fascist organisation, which would be larger, and more committed to mobilisation on the streets than the RAR could ever be. Paul Holborow, the SWP’s organiser in East London, approached two prominent members of the Labour Party, Ernie Roberts, the trade unionist and Peter Hain, the anti-apartheid activist, and the three of them together agreed to launch a movement. Holborow then became National Secretary of the Anti-Nazi League. Its founding statement was signed by Brian Clough, Arnold Wesker, Keith Waterhouse, Warren Mitchell, and several hundred trade unionists, community activists, footballers, musicians and other celebrities. Other prominent members of the Anti-Nazi League included Tariq Ali, of the International Marxist Group, and Arthur Scargill, then the Yorkshire President of the National Union of Mineworkers.

Rock Against Racism operated as the Anti-Nazi League’s kindly uncle. The success of the older movement gave ANL activists an experience of recent unity on which they could draw. The result was a remarkably successful alliance. The SWP provided the founder members of the ANL, but it insisted that the League must have an independent role. Often there were tensions between the members of the Socialist Workers Party, and the supporters of the campaigns which they took part in. Members of RAR and ANL would complain that the party was failing to take their work seriously, while members of the SWP would respond that the activists had failed to raise a full socialist politics. Overall, though, both the Anti-Nazi League and Rock Against Racism operated as successful United Fronts. So, although Widgery, Huddle, Ruth Gregory, Syd Shelton and other members of the SWP threw themselves into RAR, they never regarded it as their possession, nor would they allow other members of the SWP to impose themselves on the new movement.

While the Anti-Nazi League concentrated on confronting the fascists, Rock Against Racism continued to win young people away from the NF. The largest RAR/ANL events were the huge Carnivals, which Widgery helped to organise, as a member of the RAR London Committee. The first took place at on 30 April 1978, and began with a march from Trafalgar Square to Victoria Park, where the Clash, Tom Robinson, Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex and others played to an audience of at least 80,000 people. The historian Raphael Samuel, a member of the Communist Party from his early youth describes Victoria Park as ‘the most working-class demonstration I have been on, and one of the very few of my adult lifetime to have sensibly changed the climate of public opinion.’ This first Carnival was followed by local Carnivals in many areas. Thirty-five thousand attended the Manchester Carnival, 5000 took part in Cardiff, 8000 in Edinburgh, 2000 in Harwich, and 5000 came to the Carnival in Southampton. In every area, concerts were organised with bands like the Clash and Sham 69, which had a following among young skinheads and punks. Rock Against Racism in Edinburgh ran its own fanzine, RARE, while Gays Against the Nazis, Women Against the Nazis, Trade Unions Against the Nazis, School Kids Against the Nazis, and Civil Servants Against the Nazis also organised local groups in the town.

As already mentioned, the most important physical test of the anti-fascist movement came at Lewisham in 1977. But this whole period, from 1976 to 1979, witnessed a succession of anti-fascist demonstrations. On 14 May 1978, around 7000 Bengalis took part in a protest march against racism in Brick Lane, then the biggest demonstration by Asians that had been seen in Britain, while on 18 June 1978, 4000 supporters of the ANL and the Bengali Youth Movement Against Racist Attacks marched again through the East End. The last conflict to turn violent, was at Southall on 23 April 1979. Here the police Special Patrol Group brutally attacked Anti-Nazi League demonstrators, again failing to force a way through for the fascists. Their only success was in killing Blair Peach, a teacher, anti-fascist, and member of the SWP, who was walking away from the march when he was killed. RAR brought out a special leaflet, written by Widgery, Southall is special. There have been police killings before… But on April 23rd the police behaved like never before… The police were trying to kill our people. They were trying to get even with our culture… What free speech needs martial law? What public meeting requires 5,000 people to keep the public out?’ Fifteen thousand people marched the following Saturday in honour of Blair Peach, with 13 national trade union banners taken on the demonstration, and Ken Gill of the TUC General Council spoke at his funeral. Between 1977 and 1979, at least nine million ANL leaflets were distributed and 750,000 badges sold. Fifty local Labour Parties affiliated, along with 30 AUEW branches, 25 trades councils, 13 shop stewards committees, 11 NUM lodges, and similar numbers of branches from the TGWU, CPSA, TASS, NUJ, NUT and NUPE. The cumulative effect of this campaigning was that the NF were forced onto the defensive, and thoroughly routed. Its activists were unable to put their message across, their graffiti was painted out, and they could not march. In the April 1979 general election, the NF received a mere 1.3 per cent of the vote. Demoralised, it split into three rival factions and the Front’s support on the streets crumbled.

For Roger Huddle, writing at the time, the whole point of RAR was that it converted musical that was already revolutionary into an organisation which could live up to the music’s radicalism, ‘RAR’s fight is amongst the youth whose life style is rebellious… Punk is not just the music. It was visual, it revolutionised graphics, it’s anti-authority, anarchistic and loud. It has a lot to give RAR and RAR has a lot to give it’. One argument that followed was that the success of the ANL was dependent primarily on the radicalism of its music. This is what Widgery, Huddle and others argued in a letter to the magazine, Socialist Review, ‘Working class kids NOW are political and fun without having to make five minute speeches to prove it.’ It was also the theme of David Widgery’s book, Beating Time, ‘The ANL had shown that… the struggle on the streets set the tempo and the politicians and celebrities support and generalise but not dictate to it. It demonstrated that an unrespectable but effective unity between groups with wide political differences (the SWP, the organisations of the black communities and the Labour Party) can reach and touch an audience of millions, not by compromise but by an assertive campaign of modern propaganda.’ According to David Widgery, it was the radical and cultural politics of RAR which enabled the ANL to succeed, ‘It was a piece of double time, with the musical and the political confrontations on simultaneous but separate tracks and difficult to mix. The music came first and was more exciting. It provided the creative energy and the focus in what became a battle for the soul of young working-class England. But the direct confrontations and the hard-headed political organisation which underpinned them were decisive.’

Some of this now seemed overstated. It is not true that radical culture alone did the trick. Of course, Joe Strummer and Elvis Costello did pull the crowds to the ANL Carnivals, but at the Carnivals, there were political arguments, and these were the key. For all its anger, punk music was only ever a consequence of the music industry’s continuous desire for innovation, and as Ian Birchall has argued, punk alone did not provide any basis for a lasting process of politicisation. Widgery was right to describe the Anti-Nazi League as a synthesis, but its constituent parts were music and politics. What made the ANL such a success was its anti-racist message. Such an emphasis on politics, although different from Widgery’s account, still adds to Widgery’s credit, because within RAR and the ANL, he was one of the most articulate and consistent voices arguing that all forms of racism had to be opposed. I have already quoted his editorial from Temporary Hoarding 1. The same number also featured another Widgery article, titled ‘What is Racism?:

Racism is as British as Biggles and Baked Beans. You grow up anti-black, with the golliwogs in the jam, the Black and White Minstrel Show on TV and CSE dumb history at schools. Racism is about Jubilee mugs and Rule Britannia and how we won the War… IT WOULD BE PATHETIC, IF IT HADN’T KILLED AND INJURED AND BRUTALISED SO MANY LIVES. AND IF IT WASN’T STARTING ALL OVER AGAIN… The problem is not just the new fascists from the old slime a master race whose idea of heroism is ambushing single blacks in darkened streets. These private attacks whose intention, to cow and to brutalise, won’t work if the community they seek to terrorise instead organises itself. But when the state backs up racialism it’s different. Outwardly respectable but inside fired with the same mentality and the same fears, the bigger danger is the racist magistrates with the cold sneering authority, the immigration men who mock an Asian mother as she gives birth to a dead child on their office floor, policemen for whom answering back is a crime and every black kid pride is a challenge.

In just a few lines, this piece argued the full ANL/RAR strategy: that racism should be smashed and all the racists with it, and therefore that the fight against fascism should be turned against the racist institutions of capitalism as well.

The success of Rock Against Racism and the Anti-Nazi League ensured that the late 1970s was David Widgery’s finest moment. One of the founders of Rock Against Racism, he later became the movement’s first historian. He wrote regularly for the RAR paper, Temporary Hoarding, and helped to organise the hugely successful carnivals. The intervention of RAR, which involved Widgery along with many others, changed the sound of popular music, and helped to turn the racist tide in society, not just crushing the NF, but also turning millions of young people decisively against all forms of racist prejudice. Widgery was absolutely the prophet of the hour.

Radical in the NHS

In the 1980s, the ascendancy of Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in America combined with a sustained offensive by capital in both countries. The result was a sharp downturn in class struggle. In Britain, where strikes occurred, they lost. One by one, the steel workers, the dockers, the miners and the print workers were crushed. Meanwhile the radical allies of the working class also went into retreat, and by the end of the decade the socialist organisations, the women’s movement, the campaigns for black liberation and for gay rights had all been reduced to an organisational shell. Ironically, the values of the left became more popular than ever, but with one or two notable exceptions, the ideas lacked any force to carry them. Widgery himself seems to have suffered increasing pain as a result of the polio he had suffered as a child. With one leg shorter than other, he had been unable in the 1970s to take part in many of the large marches he had helped to organise. By the 1980s, Widgery’s illness was clearly much worse, admitting to Ruth Gregory that he was ‘in a lot of pain, a lot of the time’. Widgery drank more and smoked, and was often rude or lecherous when he was drunk. According to Syd Shelton, ‘he knew no moderation in anything.’

Dr Widgery, GP

Many of the ’68 generation were to take jobs in academia, renouncing class struggle, and turning instead towards the abstract and comforting banalities of their profession, but Widgery to his credit was not among them. Increasingly absorbed by his life as an GP in the East End, he took his inspiration and his continuing anger from the lives of the people he worked with. The first piece he wrote about his doctoring began with a description of a typical twelve hour day, ‘Forty-three consultations, 430 decisions, 4000 or 5000 nuances, eye muscle alterations and mutual misunderstandings have left me emotionally drained… But don’t pity me. I get paid quite well, by my patients’ standards. Pity the patients instead.’ The patients would be the theme of the articles which Widgery wrote from the mid-1980s for the British Medical Journal. As Juliet Ash recalls, Widgery was proud to have followed Peter Sedgwick in writing about health, and he was proud to write for the BMJ – ‘a socialist writing within such a terribly establishment body’. Three of Widgery’s books, Health in Danger (1979), The National Health: A Radical Perspective (1988), and Some Lives (London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1991), were also devoted to the politics of health. In The National Health, Widgery described how as a doctor he was continually reminded of just how important free healthcare was, ‘I had to write this book because I do care about what happens to the NHS, and I do not want to see its idealism squandered by Treasury accountants. I am an Attlee child, part of the generation shaped by Beveridge and Bevan; I got the chance to train as a doctor because of postwar education and the grammar schools; I survived childhood illness in NHS hospitals; I know what even those quite modest reforms have meant to the qualities of people’s lives; their health and human development. I cannot sit quietly by while the health service is dismantled before my eyes.’

In Some Lives, the patients moved right to the front of Widgery’s account. He described with love and humour the lives of noisy kids and gay cruisers, cancer victims, newsagents with strike collection boxes on their counters, drunk night cleaners with daughters living in Chigwell, feuding neighbours and delicate babies, lonely grandparents and coughing dockers. Although these were his patients, they were the subject and not he object of the book, and Widgery’s East Enders emerge as people with life and dignity:

What always strikes me about those condescending documentaries about the poor East Enders, ignorant, ill and probably racist into the bargain, is exactly the reverse: how well the modern Cockneys do in circumstances which their ‘betters’ would find impossible. How much better they would do if their material conditions were hoisted a few notches up the class system. And yet how much more common decency, respect for humanity, honour and humour they possess than so many of the middle and upper classes who despite lip service to collective interests in fact approach life in a spirit of naked self-interest.

Some Lives is an extraordinary social history of health and East London, and indeed London itself was now one of Widgery’s greatest loves. The book is remarkable for the ease with which Widgery moves from the detail to the general, from specific accounts of one patient’s life, to broader questions of politics and class. Widgery wrote about the politics of health with an insight and an eye for detail, which have not been matched. Raphael Samuel, himself a historian of the East End, has captured the spirit of the work, ‘The book confronts one as a kind of giant temporary hoarding on which East End lives have been inscribed themselves as so many graffiti, often obscene, always harrowing (because this is a book of sufferings), yet also comic.’ Samuel enjoyed Widgery’s gallows humour, ‘As a good libertarian, he rejoices in the Dianysiac and the transgressive. The stories usually begin staccato, as though culled from a doctor’s casebook, and this no doubt was much of their original base. But he amplified them with extended passages of oral testimony – and scraps of correspondence – which clearly go beyond the needs of the case. It is as though he was acting as an archivist for the future.’ By the time Samuel wrote this, however, Widgery had died at home following a freak accident in 1992.

Two moments from this time sum up the enormous respect which so many people had for David Widgery. The first was a speech given in an official memorial meeting by Darcus Howe, the black journalist and activist. ‘Darcus Howe said that he had fathered five children in Britain. The first four had grown up angry, fighting forever against the racism all around them. The fifth child, he said, had grown up “black in ease”. Darcus attributed her “space” to the Anti-Nazi League in general and to David Widgery in particular.’ It is a powerful compliment, yet not the most striking that David would receive. The second moment was less formal, but no less resonant in its symbolic meaning. At David Widgery’s funeral, Michael Fenn, who had been a leading activist among the dockers whose strikes brought down Heath’s Industrial Relations Act in 1972, appeared with the London Royal Docks shop stewards’ committee banner, ‘Arise Ye Workers’, which he had kept from that time. Finding the banner, bringing it to Widgery’s funeral – it is hard to imagine a more powerful epitaph for the man.

Widgery’s Marxism

This essay is an account of David Widgery’s work as a writer. I have described his political background, the way in which it shaped his work, and the impact of his writing which set the tone for the entire anti-racist movement in the late 1970s. I have barely touched on his career as a doctor or on most of his essays and his journalism, and I have hardly mentioned at all the anthologies, and the other powerful books which he wrote in the political downturn of the 1980s. What I hope, though, is that the brief account here gives a feel of Widgery dissident Marxism, which was not just an abstract project of theoretical renewal, but linked instead to a mass movement which changed the lives of millions. If the ideas of Marxism are ever to become living forces, then they must be carried in people’s hearts, and for that to happen the ideas must find their champions, people who have the talent to persuade. David Widgery was one.

This essay was first published on Dave Renton’s site

Great article

An excellent piece of writing.

I’d never heard of Widgery before – I feel inspired by the story of this great man…