The Crisis and Socialist Strategy

In the first part of a two-part essay, Ed Rooksby, assesses the economic crisis today and sketches some broad strategic principles for a radical left party in Britain.

In the first part of a two-part essay, Ed Rooksby, assesses the economic crisis today and sketches some broad strategic principles for a radical left party in Britain.

It must be clear now to all those with some grip on reality that Osborne’s austerity strategy simply isn’t working. The most recent figures show that UK GDP fell by 0.3% in last quarter of 2012 and that the economy was stagnant for the year as whole (with only a blip of growth driven by the Olympics in in the third quarter preventing overall contraction in 2012). It’s not just in Britain, of course, that austerity has plainly failed. The last quarter of 2012 also saw some of the worst GDP figures for major states in the EU: Italy minus 0.9%, France minus 0.3%, the UK minus 0.3% and even Germany saw its GDP decline by 0.6%. Eurozone GDP contracted for three consecutive quarters in 2012, following 0% growth in the first quarter. The dreadful economic and social consequences of austerity are plain to see in countries like Portugal and Spain – and, at their most extreme, in Greece.

Tragically – though it shouldn’t come as a great surprise – the Labour party leadership seem utterly incapable of offering any sort of opposition to austerity. At best they promise to cut public spending in a slightly less vicious manner than the current government. This isn’t an alternative that’s likely to inspire many people.

Radical left parties committed to fighting austerity have emerged across Europe – in Germany, in France and (most spectacularly) in Greece. We are in desperate need of a similar party in Britain – one which is willing to take the risk of seeking to break the stranglehold of a social democracy that long since capitulated to neoliberalism and present an unashamedly socialist alternative. The emergence of Left Unity is a very exciting step in this direction.

If we are going to try to build a socialist, anti-austerity, anti-neoliberal party we need to be clear about the economic and political context in which this process of construction is to take place and, from this, to extrapolate a set of strategic parameters and principles to guide us. I’d like to contribute to this process in some small way here by putting forward some broad-brush observations about the economic crisis and by making some tentative suggestions in terms of strategic orientation which seem to me to follow from these.

If we are going to try to build a socialist, anti-austerity, anti-neoliberal party we need to be clear about the economic and political context in which this process of construction is to take place and, from this, to extrapolate a set of strategic parameters and principles to guide us. I’d like to contribute to this process in some small way here by putting forward some broad-brush observations about the economic crisis and by making some tentative suggestions in terms of strategic orientation which seem to me to follow from these.

The Crisis

The Tory-Lib Dem government usually claims that the crisis was caused by ‘profligate’ public spending (although how exactly spending on schools and hospitals in the UK precipitated a global crisis is never quite explained) – and, closely bound up with this is the idea that the key pre-requisite of economic recovery is slashing of ‘unsustainable’ public debts and deficits. These claims are nonsense. For one thing, as Reinhart and Rogoff have concluded from a detailed study of 44 countries over 200 years, ‘the relationship between government debt and real GDP growth is weak for debt/GDP ratios below 90% of GDP.’ The UK’s gross public debt at the end of 2007 (i.e. before the financial crisis took hold) stood at less than 50% of GDP – which, incidentally, was far lower than the average across the Eurozone and the OECD and 10% lower than Germany’s public debt/GDP ratio. For another thing, as James Meadway points out, the ‘UK’s most sustained period of economic growth, over the post-war boom, was a period of exceptionally high public debt.’ Both the public debt and deficit shot up after the onset of financial crisis and recession, but the direction of causation is immediately obvious here – the coalition’s claim that sharp rises in public debt and deficit precipitated the crisis is, in fact, to get things back to front.

Whatever else they may be, the coalition leadership is not stupid and the political narrative they have settled on is certainly not simply a misunderstanding on their part – the claim that the crisis stems from fiscal profligacy and that, therefore, the solution is to roll back public spending is a deliberate falsification designed to justify attacks on the public sector and the welfare system. However far from the truth it may be, this narrative has been enormously successful and has now attained a sort of hegemony within popular and media discourse, largely framing the terms of mainstream debate in relation to the recession. Like many such hegemonic ideological strategies, the narrative has an uncomplicated, simple to grasp core message – that the crisis was brought on by the last government ‘spending too much’ – which can be propagated with ease through endless repetition in the Tory press and in political sound-bites. The apparent ease with which the banking crisis was smoothly and seamlessly transmuted, in the popular imagination, into a crisis of public finances bears witness to perhaps one of the most brilliantly effective ideological manoeuvres in recent political history. Unsurprisingly the Labour leadership have more or less capitulated to this narrative and do their best to reproduce it.

Widespread popular acceptance of the notion that public spending somehow caused the crisis helped to prepare the ground for Osborne’s austerity programme. As a political strategy to provide ideological cover for an assault on the public sector, this has so far proved fairly effective. As a strategy for economic recovery, however, austerity is failing miserably and is, in fact, making the economic situation much worse. As Meadway explains, there’s a simple logic to this:

Cuts in government spending shrink demand in the economy. As demand shrinks, firms sell less. Firms that sell less cut wages and make redundancies. Demand falls still further, and a vicious circle of decline is established. Cutting spending to reduce a deficit leads to bigger deficits as unemployment rises and taxes fall. Austerity is self-defeating.

As Meadway also points out, this is the sort of ‘death spiral that helped define the Great Depression’. The austerity mongers of today have simply disregarded one of the biggest lessons of the 1930s which is that governments need to stimulate demand in times of economic crisis, not suffocate it.

A defining feature of the recession today is a major crisis of demand and, intimately bound up with this, a serious deterioration in ‘business confidence’ in future growth prospects. Private sector investment has collapsed – it was noted in 2012 that investment by firms was down by about £48 billion from its 2008 peak – but there is no shortage of liquidity or savings in the economy. Indeed, the Financial Times reported last year that ‘companies globally are awash with cash’ and that UK firms, specifically, are sitting on an estimated £750 billion (Lex, ‘UK corporate tax: a missed opportunity’, FT, 12 March 2012). As Burke, Irvin and Weeks amongst others have noted, ‘No sustained recovery can take place without breaking this pattern’ – and since the private sector is unwilling to invest, the public sector must take over this investment function. The situation calls, in other words, for a classically Keynesian stimulus strategy of state driven investment to boost demand and thus, in turn, to boost ‘business confidence’.

Nevertheless it is important for the left to go beyond calls for a Keynesian type stimulus. Keynesian inspired social democratic analyses of the crisis tend to argue that it was brought on by the inherent weaknesses of the particular model of capitalism that has been dominant for the last thirty or so years – neoliberalism – and the process of ‘financialisation’ that has accompanied it. The call, from these quarters, essentially, is for the reining-in of finance capital and for a return to the much more strongly regulated, mixed-economy, model of capitalism that characterised the pre-1970s post-war order. But this does not take adequate account of the deeper, systemic determinants of the crisis. It is also far too optimistic about the capacity of the planet to absorb for much longer a return to high rates of growth in consumption. We need to develop a better grasp of the longer-term and systemic determinants of this crisis and a better appreciation of the limits to further growth which make any attempt to return to ‘business as usual’ on the part of capitalism hugely problematic.

Delving deeper

It must be emphasised that the current global capitalist crisis is, precisely, a crisis of capitalism. That is, it is a systemic crisis. It is not simply a debt crisis. The crisis is rooted in the dysfunctional logic of capitalism and, indeed, this is an extremely serious crisis which is likely to drag on for years.

The current crisis represents the breaking down of a series of temporary solutions to a major crisis of capitalism that emerged in the 1970s. In effect, the international economy has gone full circle and returned, after a few decades of (largely debt-fuelled) growth based on various temporary fixes, to the relative stagnation in which it languished around forty years ago. In order to understand the crisis today, then, we need to examine the development of the global economy over the past few decades.

Robert Brenner has argued that the advanced capitalist economies entered a crisis of profitability at the end of the 1960s. Indeed, according to Brenner, these economies have suffered from relatively low rates of profit ever since. One major reason behind the crisis of profits that emerged in the late 1960s was that firms encountered increasing constraints on opportunities for profitable investment as the post-war boom petered out. The effects of this can be seen in the marked slow-down in rates of growth from the 1970s onwards compared to previous decades (the average rate of annual GDP growth in Western Europe from 1950-73 was 4.79%, while from 1973-03 it averaged 2.19%).

Capitalism responded to this crisis in several ways. It sought to ‘go global’ in order to seek out cheaper pools of labour and to open up new investment opportunities abroad. Under Thatcher and Reagan especially, it launched an assault on trade unions and pushed up unemployment in order to weaken organised labour and drive down wage costs at home. Finance was also, increasingly, deregulated in order to soak up excess capital looking for profitable outlets. Some of the initial solutions, however, soon created further problems for capital. Repression of wages drove down workers’ spending power and thus reduced the rate of effective demand. Capital’s solution to this problem was to extend the credit system and to ramp up debt-fueled consumer spending. This strategy intertwined with wider moves to deregulate finance and with the rapid acceleration of ‘financialisation’. Credit-fueled consumption, together with asset price inflation drove growth for a while. However, this solution, in turn, eventually became the source of serious problems for capitalism because, as David Harvey notes, it ‘ultimately led to working-class over-indebtedness relative to income that in turn led to a crisis of confidence in the quality of debt instruments’. The crisis that emerged in the US ‘sub-prime’ market brought into full view the extent to which major financial institutions had become perilously overextended and, indeed, the extent to which growth had been reliant on ballooning of debt. What we saw, then, from the 1970s onwards was a series of temporary fixes to a deeper structural problem in which each fix raised further problems that had, in turn, to be temporarily solved with further fixes.

It is worth noting that ‘financialisation’ represented a response to very real pressures on profitable accumulation – it was a way of soaking up excess capital given the weakness of profitability in the productive sector. The deregulation of the financial markets and the concomitant extension of credit and debt did not simply represent, as social democratic and Keynesian theorists tend to suggest, an ideologically driven, ‘bad policy choice’ on the part of neoliberals. A solution to the problems we face then, cannot be as simple, as some sort of return to the post-war ‘Keynesian consensus’ in which financial regulation is tightened up and the financial markets put back in the box from which they escaped after the 1970s. The real structural pressures to which ‘financialisation’ was a response are still there and remain unsolved.

We must also take ecological considerations into account. There is an overwhelming consensus amongst climate scientists that the planet cannot absorb the huge amounts of CO2 currently being pumped out into the atmosphere for very much longer without triggering irreversible climate change. Furthermore, human activity since industrialisation has had a hugely damaging effect on the Earth’s biosphere as a result of demand for ever increasing amounts of food, water, mineral resources, fossil fuels, timber and so on – and this destruction is continually accelerating. Massive deforestation, pollution, destruction of entire ecosystems and species extinction are some of the effects. This ecological crisis is largely driven by capitalism’s insatiable need for expansion. The logic of perpetual accumulation for accumulation’s sake compels capitalism to plunder more and more of the planet’s resources, burn greater and greater quantities of fossil fuels and fill the atmosphere with more and more CO2. It is surely clear, however, that infinite growth on a planet with finite resources is a logical absurdity. We are approaching the point at which the planet can no longer support ever increasing rates of consumption – and thus we are approaching the point at which the economic system becomes wholly incompatible with ecological sustainability.

So we’ve seen that the current crisis is the latest (and most serious) of a series of crises that have plagued capitalism since end of the post-war boom and stems from the underlying structural problem of low profitability. We have also seen that financialisation and neoliberalism represented responses to real pressures on profits on the part of capital. Given all of this it is difficult to see how a stable, long-term solution to the current crisis can be found within the confines of the current system except through massive destruction and devaluation of overaccumulated capital (letting unprofitable firms and banks go bust) to restore the rate of profit – but this would be a dangerous strategy which would almost certainly involve an extremely serious slump. Further, we have also seen that the planet is, anyway, unable to support for much longer any return to perpetually accelerating growth in consumption – capitalism is simply incompatible with ecological sustainability.

So while, in the short term, a public spending stimulus is needed to drag the economy out of the immediate crisis of stagnation and to get people back to work we also need to develop plans for massive structural reform of the economy so that we can begin to shift society towards a new economic model which is ecologically sustainable and governed by the priority of satisfying democratically determined human needs rather than by the insatiable and destructive drive for profit.

In the second part of this essay, I’d like to put forward some ideas about the sorts of measures that a radical left party might campaign for and seek to implement as part of this wider strategy.

Ed Rooksby is a lecturer in politics and contributor to The Guardian’s Comment is Free

8 comments

8 responses to “The Crisis and Socialist Strategy”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

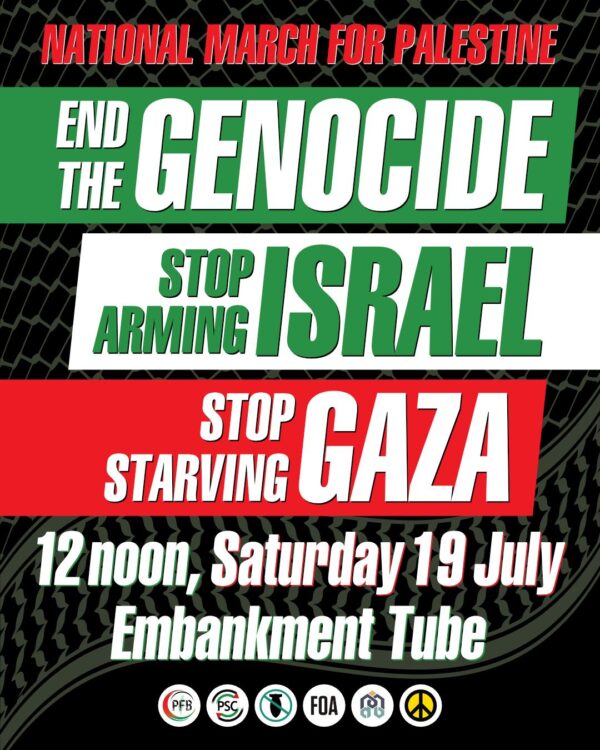

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Excellent opening overview Ed. You’ve hit all the relevant bases in deconstructing the real nature of the current worldwide systemic capitalist crisis. I look forward to Part II . The trickier bit methinks, a believable radical Left campaigning strategy , that somehow can break out from just US, the existing (relatively small – but politically significant if combined in one movement) radical left of Labour base for Left Unity , to that great mass of people we need to help break from the austerity backing, or accepting, ideological consensus so carefully and systematically reinforced by all elements of the capitalist mass media day in, day, out.

“So we’ve seen that the current crisis is the latest (and most serious) of a series of crises that have plagued capitalism since end of the post-war boom and stems from the underlying structural problem of low profitability. ”

Nonsense. Profits are at record highs.

It all spins on the difference between the rate and the mass of profit.

What we have seen under Neoliberalism is the pooling of profits through an interconnected money market. This boosts to total ‘mass’ of profits. So as an absolute figure profits are high.

However when we look at the productive economy – as opposed to the financial sector – a different picture emerges. Here there is an upward pressure on costs that eat up investment, both in terms of wages, but also infrastructure, machinery etc. Then you add in competition which squeezes prices at the selling end. This means that the rate of profit – which is the ratio between profit and cost, is constantly under pressure, which explains why capitalists are tempted into playing money markets rather than relying in the investment of profit back into their own product cycle. This is a big contradiction that capitalism cannot surmount, but one strategy they do have is to drive down labour costs, and so try and inflate the rate of profit relative to this cost. This is the story behind austerity. It also explains the link between profitability and class struggle.

Another feature of a high mass of profits is that money ceases to act as capital – it ceases to get reinvested, and acts like a hoard. Which is why corporations are posting such high cash balances. Again this is a sign of a crisis of profitability in the system. As a Marxist I always try to see what the capitalists are doing with their money. When anxious they sit on it, when confident they invest it, and when delusional they go in for Ponzi schemes.

As John says above, excellent! What a timely intervention at the start of Left Unity, Ed, covering as it does some key areas of your research interests.

Well done you again, for perceptively including an ecological dimension to your thinking. A minor point, but I was a little concerned at you only recognizing “dreadful economic and social consequences” of austerity – and that only happening in “countries like Portugal and Spain – and … Greece.” Surely it is capitalism itself, rather than merely the latest tactic of neoliberalism “austerity”, that creates these deplorable conditions; illustrated by the fact that even in the boom times, when (as you correctly describe) “the stranglehold of a social democracy” New Labour, was at its zenith, inequality grew and deprivation persisted here in the UK and elsewhere?

I am sorry to say that this meant I would only be able to award a merit, rather than distinction, for your essay; but of course I am not marking it and therefore offer these observations in a comradely spirit. However, the main force of your argument was not blighted by such trivial concerns and you are correct in not including any other factors than the environment, affecting economic decision-making – albeit in broad brush terms – in 2013, as that would be a deviation from the “unashamedly socialist alternative” you correctly seek.

A tear came to my eye as I read – not sure whether to laugh or cry – but I am sure that once the “great mass of people’, as John pithily puts it, are presented with this kind of well structured, logically argued and well referenced essay, they will soon overcome the hegemonic grip of the Tories and their accursed mass media, see the “utterly incapable” Labour leadership for the craven bunch they are and join Left Unity in droves; voting for us in local, national and European elections; actively participating in Left politics in a way that has not been seen since the miners strike and helping to create a significant political force, capable of facing the challenges humanity faces in this epoch. [ That was sentence disguised as a paragraph. Good job I’m not writing an essay, as I’d probably lose marks too! ]

Indeed, now that the aforementioned Great Strike is well and truly behind us, and those post-Marxist pessimists have long since stopped harping on about what an historic defeat it was and how we had to really think afresh about how we (i) conduct struggle, (ii) think about ‘the working class’ and other oppressed minority groups, such as women, (iii) make alliances, and lots of other defeatist nonsense; we can now really think afresh and not get lost in complex analyses, but think cogently, as your admirable essay does, then act decisively as comrade Scargill did back in 84-85. If only Kinnock and those other traitors had supported Arthur and our lads back then; if only those Welsh and Scottish miners – and even some in their own ranks – had stood firm with the great majority of Yorkshire lads, and of course our brave lasses, it could have all been so different. But I may be stealing your thunder?!

I’ll wrap up here, as I don’t want all this praise to go to your head and distract you from the important task of completing part two. Well done you once more and keep up the good work.

This article probably echoes the problems that a party trying to unite the left will have: it’s tries to incorporate multiple points of view & ends up trying to be both reformist & revolutionary.

The first point to note though is understanding & explaining just how capitalism works & the nature of its crises is difficult. We should show some humility (I don’t think Ed comes across as being dogmatic).

The second point is although capitalist crises are difficult to explain & the left has a number of explanations, we should be defining the left as anti-capitalist. If you are not against capitalism then you are not a revolutionary & merely want to reform capitalism to make it fairer. If this is the case join Labour or the Green Party. If you are anti-capitalist, & I presume Ed is, then it needs to be spelt out that Keynesian fiscal stimulus cannot resolve the crisis. Being against austerity doesn’t mean you are for fiscal stimulus! Price inflation hurts workers by cutting their real wages as much as cuts in nominal wages do. Keynesians are capitalists, (Keynes was no socialist) & their support of inflationary policies doesn’t make them on the side of the workers.

As for the nature of the crisis, to say that it’s “a major crisis of demand and, intimately bound up with this, a serious deterioration in ‘business confidence’ in future growth prospects” is a Keynesian diagnosis to which a solution is fiscal & monetary stimulus. But you then sketch out an explanation that I have long argued. I would term it a crisis of overproduction – an overproduction of commodities relative to what can be realised over the longer term. An overproduction that has occurred due to excessive credit/debt, part of which has now been moved from the banking sector onto the government books. And yes, now their disingenuous argument about the need for austerity. Although in a wider sense they are quite right that capitalism cannot afford a dent welfare state any longer. This does indeed seem to be because behind the excessive debt lies a problem producing surplus value – a falling rate of profit. This is hard to be absolutely sure about as it’s hard to measure a ‘true’ underlying profit rate not inflated by credit/debt. Indeed, it’s very difficult to even measure the size of the overproduction & how much fictitious capital needs to ‘go up in smoke’. We know Kliman provides some interesting statistics about the fall in the US profit rates in the late 1960’s & how they are tied to rises in the organic composition of capital after WWII. A 1930’s depression was seemingly avoided by the introduction of a fiat money regime & associated financialisation, although it’s also fair to recognise the positive impact industrialisation in China has on profit rates along with the demise of the Soviet Bloc.

We are probably now at the situation where the required devaluation of capital is so great that that the resultant workers response will challenge the continuation of the system. A devaluation that is required for all the surviving claims on future labour time to have any chance of being met. A devaluation that is to do with the problem of realising surplus value. But as Ed rightly says, in my opinion, there is then the deeper problem of profitability. The gains from cheap energy (oil essentially) are now history. The post-war rises in the rate of exploitation that coincided with improving living standards for the workers are unlikely to return any time soon. If anything the increasing price of energy has put these gains into reverse. There is now a direct attack on workers by capitalism (bosses & the state).

So for the ‘left’ to get anywhere & no drift back into nostalgia about 1945 or 1968 it must be overtly anti-capitalist. No only is this good politics in the long-run, it will actually get a lot more votes. Be against the system & not trying to be a group of people that could run capitalism on a fairer basis. That means don’t give any credence to Keynesian capitalist solutions as this will only help sell-out a revolution later on.

Bill, John and Joe – thanks for the replies. Bill – I’m aware that there are various controversies in relation to crisis theory. If you’re the same Bill Jefferies that I think you may be, I’m also aware that you’ve long disagreed with the generally Brenner type argument. You may be right, I admit. Probably unsurprisingly I agree with Joe though.

Ben

Sarcasm sort of loses its pithiness after, say, five or six laboured paragraphs. Don’t let anyone tell you that sour pettiness isn’t a good look which people always find very attractive though.

Ed, I am hurt and wounded by your cruel comments, you have obviously misunderstood. I think that originality of the kind you open your essay with: “It must be clear now to all those with some grip on reality that Osborne’s austerity strategy simply isn’t working” will have the aforementioned masses riveted to their screens and knocking at the virtual door of LU.

People too often look down on banality. The simplicity of slogans like “Fight the cuts!” remind me of our heyday back in the good old 1980s, when we marched and chanted “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie – out, out, out!” And that worked a treat, as eventually we did get her out; and now she’d “… dead, dead, dead!” – even better!

I lol at the implied critique of Mouffe and Laclau in your title! You certainly give those misguided reformists a run for their Euro (ha ha). Roll on part two!

Dear Ed

Thank you for this excellent summary of the crisis in capitalism. These are some of my immediate thoughts on reading it:

First thought: your ‘short term’ solution to the crisis in demand is a public-spending stimulus, but surely the problem is that the whole notion of ‘demand’ must change, if the planet is to continue to be able to sustain the human population…even though this would only be a short-term solution, is it not a paradox – and how can the left formulate a policy on sustainable living (an end to the current concept of demand) if we are at the same time promoting a policy which stimulates demand?

Second thought: how many people will read this? I found myself musing ruefully on the idea that if your article were to be transformed into a slick three-minute video clip, it would go viral…I’m afraid that is the main method that meaning is conveyed and imbibed by the young people I teach nowadays.

Final thought: I am not an economist, but am also very keen to make the point that non-economists do understand this crisis (thanks to people like you Ed, who write so lucidly about it) and should not be afraid to contribute to the debate. The mass media have peddled two big lies: that the crisis was caused by ‘everyone living beyond their means’ and that austerity is the only solution now. But there is an even bigger, hidden lie behind these – that ordinary people cannot understand economics and must put their blind faith in their rulers now – which could lead to a historical backward step in terms of mass political participation, and worse, mass blind faith in some charismatic fascist leader who may well emerge to fill the current political vacuum.

So the message of all of us on the left should be: every day, engage someone in a conversation (real or online) about the way forward out of this crisis. Get people involved in this debate – we need a ‘critical mass’!