Podemos 2.0: The accelerated evolution of the Spanish radical left

Antonio Martínez-Arboleda looks in detail at the birth and growth of Podemos, and the debates now around open electoral platforms.

The Left in Europe is celebrating the electoral results of Podemos and other left-wing political forces in the 24 May 2015 Regional and Local Elections in Spain, where strong clusters of popular enthusiasm are growing. A tsunami of street and digital art and debate, whose mass-appeal can be traced back to the 15-M Revolution of 2011, is providing the colour and the joy of this progressive, although demographically unequal, change in the collective mood. “Fear is changing sides” (one of the many Podemos mottos).

Image: Manuela Carmena, mayor of Madrid, in traditional Madrid’s costume. Photo from Ahora Madrid Facebook page

Image: Manuela Carmena, mayor of Madrid, in traditional Madrid’s costume. Photo from Ahora Madrid Facebook page

It is very difficult to provide an aggregate percentage of votes obtained by Radical Left parties. Apart from Podemos and IU (United Left, a party made out of many parties, the strongest of which is the PCE, Spanish Communist Party), a myriad of popular platforms, coalitions and local parties presented candidates. However, it is safe to say that the percentage of votes for the Radical Left did not exceed 21% overall. The results contrast with the higher expectations generated by surveys at the end of 2014 that estimated the voting intention at 28.3% just for Podemos alone (Sigma 2 Survey, carried out between 17 and 19 November 2014).

The fragmentation of the Radical Left is stubbornly evident. Whereas the popular voice seems to indicate overwhelmingly the need for confluencia (popular unity, confluence), the party leaders and their most committed party ranks continue to maintain relatively uncompromising attitudes. This division may have played a role in the May 2015 electoral results, as many voters do not like wasting their vote on parties who do not have a real chance to win.

In this article we look at the organisational challenges and opportunities for the Radical Left in Spain, pointing at hopefully revealing details that, in my view, are essential to consider. Sadly, the political nuts and bolts tend to be ignored in most articles on Podemos in the media because of the difficulty to fit in the nitty-gritty in shorter articles, sometimes written with, understandably, little information about what goes on at ground level.

Two important clarifications: a) Questions such as the ideological underpinnings of the different Radical Left groups, their political discourse, or the digital and educational aspects of the political processes are fascinating, but will not be dealt with in this article, except, tangentially, when it comes to the model of participatory democracy that different actors seem to embrace. b) The term “Radical Left” is used here in a very inclusive way. In my view, the “radical” component that all the Radical Left parties mentioned in this article share is their commitment to a policy change of 180° on issues such as austerity, environment, public services, economic power and socio-economic rights. If we were to use a label and a location in the political spectrum, we would say that these parties encompass activists with social-democratic, revolutionary socialist, communist and anarchist convictions, situated notably to the left, in terms of actual policy proposals and practice, of social-liberal PSOE in Spain and Labour in Britain.

The birth of Podemos

In January 2014, a group of Spanish intellectuals and activists signed a manifesto called “Mover ficha: convertir la indignación en cambio político” (“Moving piece: transforming indignation into political change”, in literal reference to making a move in a chess or draughts game, following the 15-M Indignados protests). The document was promoted by Izquierda Anticapitalista (The Anti-capitalist Left). It called for an electoral response to the policies within the EU that were to blame for austerity and the crises. Two days later Pablo Iglesias, a university lecturer in politics, was leading the initiative under the name of “Podemos” (“We Can”). The plan to co-opt Iglesias as the visible head of Podemos had been code-named “operación coleta” (Operation Ponytail, in reference to his hair style) by the founding group of Podemos.

Image: Pablo Iglesias in a TV programme with ultra-liberal media star Federico Jiménez Losantos

Image: Pablo Iglesias in a TV programme with ultra-liberal media star Federico Jiménez Losantos

Pablo Iglesias was well known in the Left because of his previous activism in Radical Left organisations, notably United Left, and his own work in local alternative TV channels in Madrid. His popularity reached national levels and wider audiences with his appearances in mainstream TV channels from 2013, including two right-wing channels where he would be given the role of sparring for recalcitrant neo-liberal and blood-thirsty Spanish commentators in political show-debates. In hindsight, giving Iglesias a platform, even though it was often bitterly hostile, seriously backfired against the interests of the Spanish Right.

Almost in parallel to these TV appearances, Iglesias had started to build a relationship with the online newspaper Público, where he began to write in 2012 as a columnist. In 2014 Público was hosting Iglesias’ Digital TV programme La Tuerka, the revolutionary news and debate show where his friend and colleague, Juan Carlos Monedero, also part of the founding group of Podemos, would appear in broadcasting roles with a visible sticker of Gramsci covering the apple on his Mac.

Image: Juan Carlos Monedero in La Tuerka

Image: Juan Carlos Monedero in La Tuerka

Podemos’ growth

Podemos obtained 5 MEPs (7.98% of the vote) in the May 2014 European election, a surprisingly good result. Its appeal to the 15-M Revolution (Indignados) activists and sympathisers, many of whom became members of the movement, as well as its media strategy, were key in its success. Podemos was close to overtaking the other major Radical Left force, United Left, whose platform for that May 2014 election, “Izquierda Plural” (“Plural Left”), which included some Galician and Catalan left-wing parties, obtained 6 MEPs (9.99% of the vote).

Podemos continued to build its strength in popularity. In autumn 2014, between 15 September and 15 November, the party held a massive, open, predominantly online founding assembly that led to the enactment of its current Statutes, the election of its General Secretary, Pablo Iglesias, and the election of its State-wide Citizen’s Council. During this clinically organised, visually attractive constitutional process, which was dominated by messages of hope for the people, hate of the establishment (“la casta”, “the caste”) and a viral wave of activism in the local Círculos (Circles, open assemblies of Podemos), the membership grew to more than a quarter of a million members, all registered online.

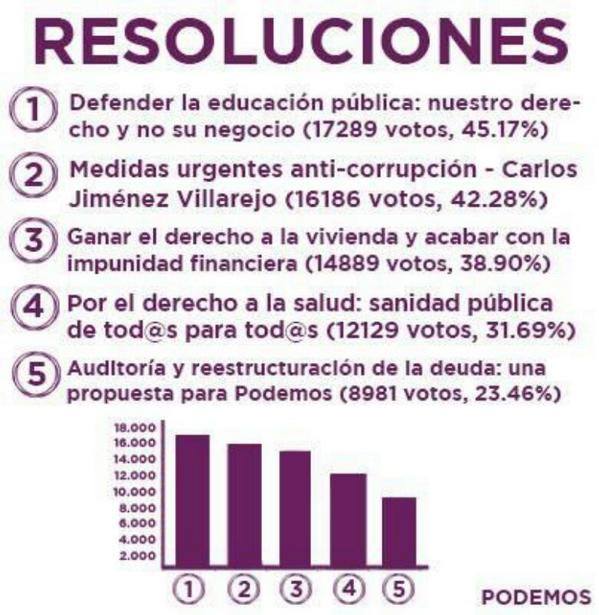

Image: The 5 most voted popular initiatives in the Podemos Assembly in autumn 2015. Photo from Podemos Granada Facebook

Image: The 5 most voted popular initiatives in the Podemos Assembly in autumn 2015. Photo from Podemos Granada Facebook

The initial battle around Podemos’ structure

If we look at Podemos’s Statutes passed in the Autumn 2014 Assembly, it is clear that the party opted for a highly centralised structure, far more hierarchical than most activists coming from the 15-M movement would have wanted.

Iglesias’ proposal for the Statutes, under the brand “Claro que Podemos” (“Of Course We Can”), received mass support. The leading group within Podemos, the ruthlessly effective Circle at the Universidad Complutense led by Pablo Iglesias, had managed to persuade a substantial majority of members of Podemos during the Assembly period of the need to have a very united and solid party structure. Podemos had to become a true war machine in the elections. Iglesias had threatened, in a major speech delivered in the physical venue of the Assembly, in Vistalegre (Madrid), that he would not take the role of General Secretary, if elected, unless his model of party was also given the green light.

Additionally, as part of the centralising strategy of Iglesias and Íñigo Errejón, a key figure in this process, Podemos approved in the Autumn 2014 Assembly the prohibition of ‘double militancy’: anyone wanting to have an internal position within Podemos would have to give up membership of other political parties. This decision was considered an attack on Anticapitalist Left, the party whose contribution to the birth of Podemos, back in January 2014, was essential. This prohibition became an organisational principle that would shape any future process of confluencia.

Image: “Of Course We Can” Facebook profile picture

Image: “Of Course We Can” Facebook profile picture

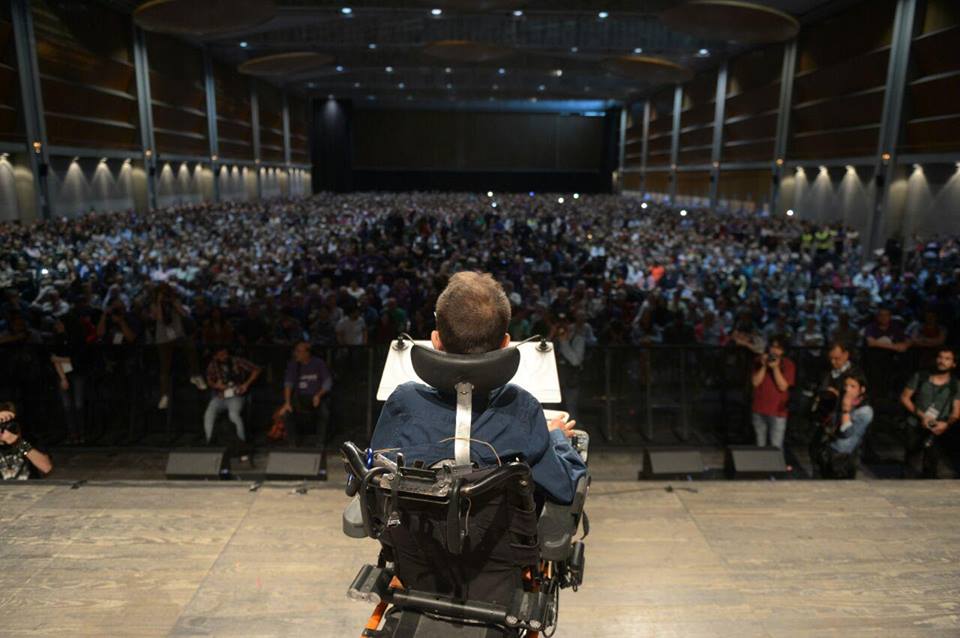

The victory of the “Of Course We Can” project was a huge drawback for a highly visible sector of activists, including the charismatic Pablo Echenique, the Anticapitalist Left and other groups who had been working together in their Circles on their own projects of Statutes. The different strands of the opposition did not manage to organise themselves that effectively around one single alternative proposal of Statutes. However, most of the critics were happy to live under the “Of Course We Can” regime and work enthusiastically and loyally towards the party’s goals. On paper, the party’s Statutes still allowed for a plurality of voices being represented within the structures at different levels. Anticapitalist Left, in a sign of astute pragmatism and faith in the original Podemos project, opened an internal process to define their position. As a result of this, they ceased to be, legally, a political party in January 2015 and became an “association”. Their new status prevents their organisation from running for any elections, but it enables Anticapitalists’ members to maintain a space of reflection, discussion and action without being excluded from Podemos.

Podemos’ centralising strategy

The centralising strategy of “Of Course We Can” had two other strands beyond the letter of Podemos’ Statutes:

Firstly, as caretakers of the party during its process of constitution, the Iglesias group had managed to impose block-voting as the most accessible and visible option for e-voting. This helped “Of Course We Can” to take up all the 65 positions of the directly elected members of the State-wide Citizens’ Council in the October 2014 internal elections, in which Pablo Iglesias was also elected General Secretary.

Secondly, Iglesias and his group not only used his own internal brand to advertise their project of Statutes during the Autumn 2014 Assembly. The motto “Of Course We Can” would also, from this point onwards, be used to compete as a brand in all the Podemos’ internal processes for the election of members of regional and local Citizens’ Councils and for the primaries for candidates for the Regional Elections. Effectively, “Of Course We Can” became the “official” and dominant tendency within Podemos. Íñigo Errejón, number 2 of Podemos, was instrumental in the implementation of this strategy and is considered its strongest supporter.

Iglesias’ brand “Of Course We Can” obtained significant majorities of seats in the regional and local structures across the country held in December 2014 – January 2015, controversially by presenting full lists with personal endorsement from Iglesias and his group and promoting block-voting. They also managed an overall victory in the primaries for Regional Elections at the end of March 2015.

Image: Iñigo Errejón’s Facebook profile picture

Image: Iñigo Errejón’s Facebook profile picture

The selection process for candidates in the officially endorsed “Of Course We Can” lists is a big point of contention. The precise methodology followed by the leadership in Podemos in order to create a vast network of “Of Course We Can” candidates is unknown to the public. Critics claim that Iglesias and his group relied on personal contacts, secretive meetings and guesswork. Not being identified with the internal opposition to Iglesias during the process of discussion of the Statutes was the most obvious requirement.

Supporters of “Of Course We Can” find justification for the methodology adopted by Iglesias’ group in the need to include the most qualified people for the job, rather than just the most popular with the grassroots. “Of Course We Can” was trying to engage with middle class and centre-left voters by placing a focus on the academic and professional status of their candidates.

These selection methods were perceived as elitist and undemocratic by the critics, whose most visibly organised strand is Anticapitalists. They claim that the “Of Course We Can” selection methods contribute to the formation of the type of loyalty links within the party that the new politics of Podemos intended to eliminate in the first place, creating unwelcome divisions between “the chosen” or “the most capable” and the rest. In contrast with “Of Course We Can”, most of the critics used open pre-primaries for the selection of candidates for their alternative lists in all the internal processes.

In my view, there is one more criticism to be made to “Of Course We Can”: the process was conducted inefficiently because the leading group in Madrid had to rely, hastily, on sometimes difficult to control contacts in the regions, who would then make decisions on the basis of friendship and other personal allegiances. The job of “selecting the best people” based on the imprecise criterion of “competence” is a hard one.

It must be said to Iglesias’ and Errejón’s credit that their victories in the internal electoral processes were achieved in full compliance with their Statutes and with mainstream liberal conventions about democracy. Also, Iglesias’ team must be praised for their key contribution to the media and electoral achievements of the party. Part of their success comes from the relative absence of public discrepancies resulting from the effective net of loyalty links built by “Of Course We Can”.

The critics

We need to understand the legitimate frustrations of the critics, many of whom see themselves as the custodians of the spirit of the 15-M Revolution: they saw themselves outnumbered in the party by exclusively online and relatively faceless militants (the number of people registered online reached 250,000 during the Assembly and is currently over 350,000); many felt betrayed by those members who had decided to join “Of Course We Can” after having received an invitation, sometimes abandoning or postponing their autonomist/anarchist convictions about grassroots democracy; there is a sense of being marginalised by the General Secretary and the Committees of the party amongst the critics, who cannot see themselves identified with anyone in positions of responsibility in the party; in general, the critics have become increasingly disenfranchised and frustrated. We must bear in mind that many critics do not have a group outside Podemos, such as Anticapitalists, to identify with.

Clearly, Iglesias’ concentration strategy has not dealt with the conflict between the two souls of the party (the centralist versus the autonomist/anarchist). It has simply devolved the confrontation to the grassroots. Iglesias and his group had several opportunities to provide a “living together” role model to the rest of the party, by having a voting system that would enable the representation of different tendencies in the State or Regional Citizens Councils, for instance, but they wasted them.

Image: Carlos Egio (left), Podemos MEP Lola Sánchez (centre) and Gonzalo González in an event organised by “Ahora Podemos (Now We Can) Murcia”, one of the many alternative lists to “Of Course We Can”. From Ahora Podemos Facebook page

Image: Carlos Egio (left), Podemos MEP Lola Sánchez (centre) and Gonzalo González in an event organised by “Ahora Podemos (Now We Can) Murcia”, one of the many alternative lists to “Of Course We Can”. From Ahora Podemos Facebook page

Despite the frustration of the critics, there is also a shared understanding amongst many of them that Podemos is their party as much as Iglesias’, that the party´s ethos, mechanisms and policies are superior to those of any other party with some hope of victory and that it is essential to stay inside the party in order to maintain their influence in this game-changing political force.

It is also worth noting that the degree of ideological and strategic dissidence amongst the critics varies. The alternative internal electoral lists and the discussion groups, notably in WhatsApp and Telegram, have also become a harbour for anyone in Podemos who wanted to help to build the party and did not happen to be invited to be part of the “Of Course We Can” group in their region or city.

The critics’ victories

In some regions, the alternative lists to those of “Of Course We Can”, under names such as “Ahora Podemos”, (“Now We Can”) managed to obtain some representation in the internal structures during the winter of 2014-15. The most significant victories for the supporters of ‘bottom-up’ democracy came later, in the Podemos primaries for the Regional Elections. The immensely popular Anticapitalist Teresa Rodríguez and Pablo Echenique (who had resigned as an MEP to participate in regional politics) became the Podemos candidates for presidents of the Regional Government in Andalucía and Aragón respectively. In the Region of Madrid, the result for the internal election for candidates to the Regional Elections of March 2015 was a very close tie between “Of Course We Can” and the opposition. The critics across the whole of Spain identified themselves invariably around grassroots participatory democracy and open pre-primaries.

Image: Cover photo of Pablo Echenique’s Facebook page. Echenique, a very prestigious scientist as well as a political leader, in a rally in Zaragoza in May 2015.

Image: Cover photo of Pablo Echenique’s Facebook page. Echenique, a very prestigious scientist as well as a political leader, in a rally in Zaragoza in May 2015.

At local level, the City of Cádiz, whose province is dominated electorally by Podemos, has now a Podemos mayor, José M. González “Kichi”, who ran in the election as part of an open platform. Kichi, another Anticapitalist, has replaced in his City Council office the portrait of Juan Carlos I, the former King, with that of Fermín Salvochea, a local anarchist who became Cádiz´s mayor during the times of the First Spanish Republic, in the 1870s. Salvochea is well known for his unparalleled generosity and his tireless political activism at difficult times for the Spanish Revolutionary Left.

At the time of writing this article there are a number of open meetings and initiatives organised by groups of critics in different regions in defence for a greater degree of internal and external inclusiveness in Podemos’ structures, like the 28 June 2015 meeting in Madrid “Podemos desde abajo” (Building Podemos ‘bottom-up’).

Podemos in the 2015 regional and local elections

Podemos initial internal cracks seemed not to matter, as it continued to grow considerably in terms of appeal to voters during autumn 2014. In November 2014 it became, according to the Metroscopia survey, the first party in voting intention, with a 22.2%, in contrast with 13.1% for PSOE (The centre-left “socialist” party) and 10.1% for PP (Conservatives). The Sigma 2 survey even gave Podemos 28% at the end of November 2014.

During winter 2014-15 different surveys, using different methodologies, kept giving Podemos a relatively close tie with the other two parties, sometimes as the second political force, but progressively as a third. Podemos had started to lose strength and this was more visible in March 2015, coinciding with three events:

1) The rise of Ciudadanos (“Citizens”), the Catalonia-based party that had recently opened branches across the whole of Spain. This party, with a liberal ideology, a strong anti-corruption message and Spanish nationalist undertone and policy, has had the support of the right-wing online newspaper Libertad Digital, formerly supporting the liberal wing of the PP. Citizens is seen by many as the Podemos of the Right because whilst being liberal, it demands transparency and ethics, their leaders are young and refreshing and the party is committed to open primaries for the selection of candidates.

2) The electoral campaign for the 22 March 2015 Regional Elections in Andalucía, won by PSOE, although not by an absolute majority (Podemos came 3rd with 15% of the vote).

3) A greater visibility of the internal debates within Podemos, not only around the perceived centralising and managerial administration of the party but around the softening of its more radical policies and messages. These debates were amplified by the rise in internal activity and media coverage resulting from the Andalusian Regional Elections.

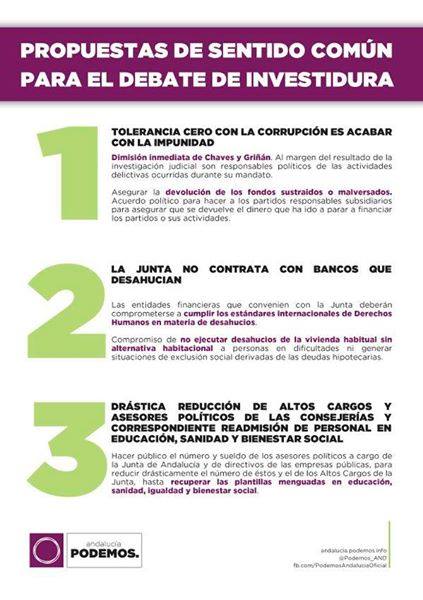

Image: The 3 red lines that Podemos set for any agreement with PSOE after the Regional Elections in Andalucía in 22 March 2015. From Podemos Facebook page

Image: The 3 red lines that Podemos set for any agreement with PSOE after the Regional Elections in Andalucía in 22 March 2015. From Podemos Facebook page

Regional elections

In May 2015, local elections across the whole of Spain and elections for 13 out its 17 Autonomous Communities (and the two Spanish Autonomous Cities of North-Africa, Ceuta and Melilla) took place. The Governments of Galicia, Catalonia, Andalucía and Basque Country have the statutory powers to call for their own elections and they rarely coincide with any State-wide election.

The most salient feature of the results of this election is the composition of the new regional parliaments: there isn’t a single one of them where one party has an absolute majority. Surprisingly, the PP (Partido Popular), despite being on its knees following an astonishing number of high-profile corruption cases, some leading to incarcerations, and the dire economic situation for a great deal of the population, has managed to maintain a strong electoral position. They still continue to be the most voted party in Spain.

The overall results of Podemos in the May Regional Elections (around 17% of the vote) were roughly similar to those obtained in the 22 March 2015 Regional Elections held in Andalucía. Podemos is currently the third electoral force in most of the regions where elections took place. The best regional results were obtained in Aragón (20%), Asturias (19%) and Madrid (18%) and the worst in Extremadura (8%). These types of percentages allow parties in Spain to obtain a decent amount of seats in the regional parliaments thanks to the relatively proportional electoral system.

Naturally, the rise of Podemos has brought about the electoral diminishing of United Left. Podemos has currently 134 seats across the different Autonomous Parliaments of the whole of the State (3 of these parliaments had their latest elections when Podemos still did not exist) whereas United Left has currently 22. In this election Podemos has even beaten the best ever result of United Left, which was a 13.44% of the vote in the European elections of 1994. It is worth noting that the fragmentation of the Radical Left in Spain stems also from the weight of parties that operate exclusively in the territory of their Autonomous Communities, not just from the Podemos / United Left split. Full results of the 24 May 2015 elections.

Is Podemos collaborating in coalition governments or, at least, facilitating the formation of PSOE minority governments? It seems that, in general, the liberal Ciudadanos are slightly more inclined to facilitate minority governments of either PSOE or PP than Podemos is to lend any support to PSOE in the regions (or PSOE to accept it).

The recent agreement between PSOE and Ciudadanos in Andalucía, after much internal wrangling and audio-visual red-line showcasing by Podemos, has enabled Susana Díaz (PSOE) to become president. At the time of writing this article, the agreements between PP and Ciudadanos to control the regional parliaments of Madrid and Murcia are finalised. Meanwhile, Podemos has reached post-electoral agreements only in Castilla-la Mancha and Extremadura, with PSOE, and in the Balearic Islands with PSOE and MES (greens/nationalists). These agreements, once negotiated, were approved by the members of Podemos in online consultations.

Local elections

Local elections were held at the same time as the regional elections, simply with different ballot boxes and papers. At this point it is essential to remember that Podemos’ General Assembly had agreed, back in autumn 2014, that the party would not run in any local elections under its own banner. Podemos feared that organising local elections and electing and vetting candidates for more than 8,000 councils, some as big as Madrid, many of them tiny hamlets, would be a risky undertaking that would distract them from the objective of winning the autumn 2015 General Elections.

However, the Podemos’ General Assembly allowed its members to integrate into existing open electoral platforms for local elections as candidates, or even to initiate their own platform, providing that there was no protagonism whatsoever given to any party within the platform and that the platform shared Podemos’ political principles, including open primaries for the selection of candidates. These open platforms, generally integrating parties such as Podemos, United Left, Equo (Greens) and many small organisations and independent citizens, have been a greater success than Podemos itself, in particular in the two biggest cities of Spain: Madrid and Barcelona.

In Madrid, Ahora Madrid (Now Madrid) obtained 31% of the vote and 20 seats, a very close second to PP (Conservatives), which obtained 34% and 21 seats. The PSOE, third party in the city, with 9 seats and 15% of the vote, agreed very soon after the election to vote in favour of the candidate of Ahora Madrid, the independent Manuela Carmena, to become the new mayor of the city. Interestingly Ahora Madrid obtained 31% of the vote in the city of Madrid, whereas Podemos obtained, in the same city and on the same day, but for the elections of the Region of Madrid, only 17%. Around 40% of people who voted for Ahora Madrid would not vote for Podemos in the city of Madrid.

In Barcelona, the local platform, Barcelona en Comú (Barcelona in Common) won the local elections with 25 % of the vote and 11 seats. The other left-wing forces, including PSC, the Catalan version of PSOE (5 seats), the pro-independence ERC (4 seats) and CUP (3 seat) all voted in favour of Barcelona en Comú’s independent candidate, Ada Colau, to become the mayor.

As no regional elections were held in Catalonia in 2015, it is difficult to compare the strength of the open platform in the Barcelona local elections with the strength of Podemos in Barcelona city at the Catalan level. However, considering the internal diversity of Barcelona en Comú and the fact that Podemos sits on the fence when it comes to the question of the referendum for independence, it is wise to say that the results of this open platform exceed considerably any realistic expectation about the vote that Podemos alone would have obtained in that city in a Catalan election.

Image: Barcelona’s mayor, Ada Colau, being taken away by police in Barcelona forces during a protest in July 2013. Photo from Ada Colau’s Facebook page

Image: Barcelona’s mayor, Ada Colau, being taken away by police in Barcelona forces during a protest in July 2013. Photo from Ada Colau’s Facebook page

Other big cities in Spain, and some medium-sized ones, had also open platforms in which Podemos members became involved: Cádiz, where a Podemos mayor is now ruling, Zaragoza, A Coruña and Santiago, in Galicia, Seville, Murcia, etc. However, not all the open platforms can claim a clean sheet, as will be explained later.

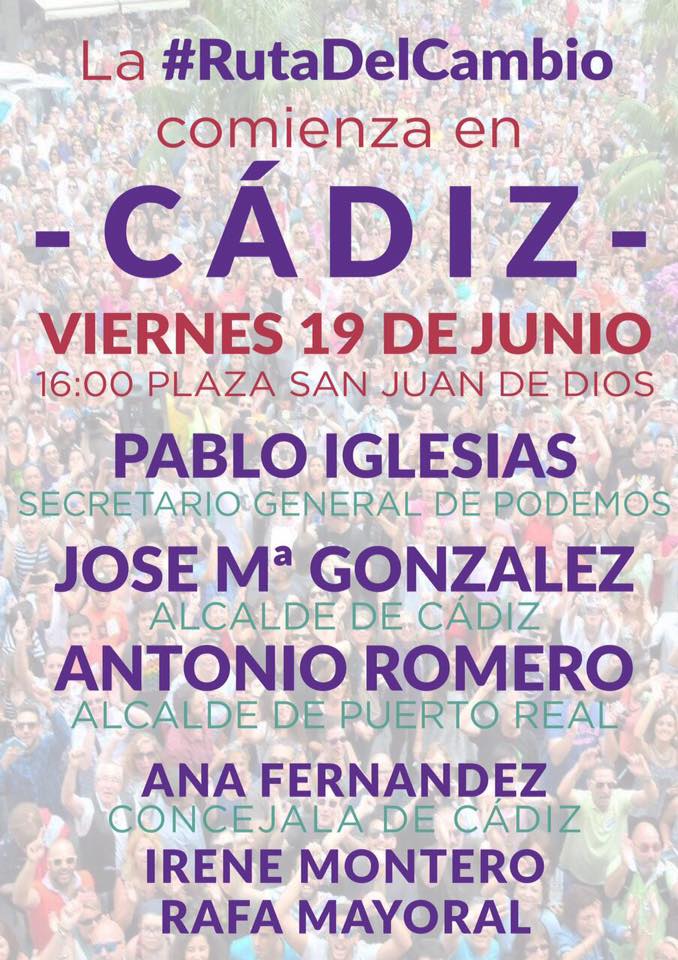

Meanwhile, Pablo Iglesias, conscious of the clout of Kichi (Cádiz), Ada Colau (Barcelona) and Manuela Carmena (Madrid) has organised very well targeted and defined rallies in those three cities trying to capitalise the victories of the platforms that these mayors were part of. This is one of the key ingredients of Iglesias’ #Rutadelcambio (Route for Change) initiative.

Image: One of the events of “Route for Change” with Iglesias and Kichi

Image: One of the events of “Route for Change” with Iglesias and Kichi

Popular unity platforms: Podemos 2.0?

At the moment, Spanish politics is a constant flow of debates around the role of Radical Left parties and organisations in constructing a winning alternative, particularly in the light of the leading position gained by Podemos. These discussions are connected with Podemos’ internal developments.

The success of the open Radical Left Platforms in Madrid and Barcelona triggered strong demands for Podemos to adopt a platform electoral model for the autumn 2015 General Elections. These pleas for unity come from some groups inside Podemos, from Radical Left voters and activists and also from United Left, whose Federal Presidency approved officially to pursue that option on 5 June 2015. The idea of confluencia seems to be gaining more and more momentum.

On the 21 June 2015, a group of activists from different forces, including Podemos, Equo, United Left and, interestingly, PSOE, decided to launch their initiative the group “Somos Izquierda” (“We Are Left”) in support for a much wider electoral platform. Their announcement almost coincided with the 23 June headline of Diario Público preparing the terrain for a future government coalition with PSOE by suggesting that PSOE, Podemos and United Left votes together in the autumn general election would exceed those of PP and Ciudadanos together.

However, the official line of Podemos about the integration into open platforms of Popular Unity (one of their most recent denomination) has been so far dismissive. For Iglesias, Podemos is open enough to welcome anyone who shares its principles. Podemos is seen as “the platform” itself, or the vessel for the journey (Spanish political discourse is becoming increasingly literary since Podemos).

Some supporters of the official line of Podemos, like Germán Cano, claim that the success of Ahora Madrid and Barcelona en Comú should be attributed to the popularity and personal charisma of the two women who ran as top of their respective lists. Ada Colau is known as the leader of the anti-eviction platform PAH. Her powerful yet honest rhetoric and her personal stance in peaceful actions of civil disobedience has given her the status of heroine. Manuela Carmena is a human rights activist and lawyer who fought against Francoism and has led social-economy projects. In consequence, for Iglesias and his group the way forward is not to integrate Podemos in open platforms but to attract more people like Ada and Manuela to Podemos. Some have even suggested that if Podemos had not supported the open platforms, the visibility and clout of those platforms would not have been sufficient for them to make any substantial difference in the elections. Interestingly, Ada Colau and Manuela Carmena are not and do not seem to be willing to become members of Podemos, despite their apparently excellent relationship with Iglesias and Podemos.

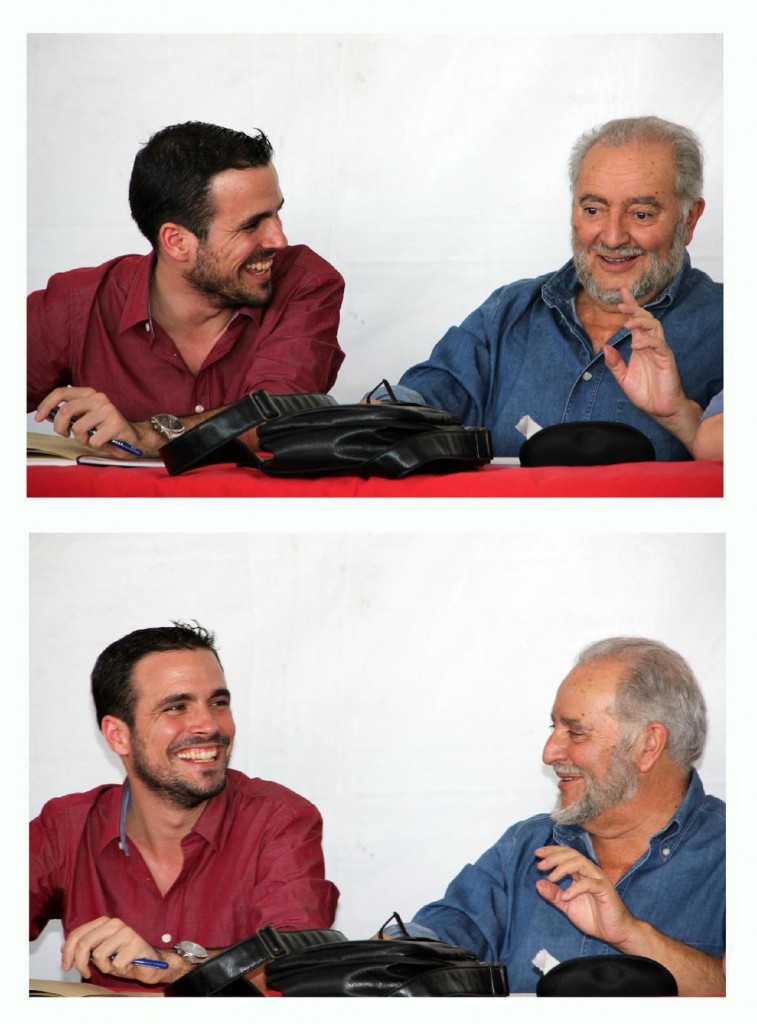

Image: Alberto Garzón, candidate of United Left for the presidency of the Spanish Government (left) with Julio Anguita, founder of United Left.

Image: Alberto Garzón, candidate of United Left for the presidency of the Spanish Government (left) with Julio Anguita, founder of United Left.

The debate about the platforms has been particularly bitter because Iglesias and others, despite showing personal appreciation to some of the United Left leaders, have used insensitive language when referring to the rival party. Comparisons have been made between United Left and a sinking boat. Iglesias himself said that Podemos is not to come to anyone’s rescue. Accusations of sectarianism and inward-looking attitudes against United Left and its Communist Party are common place. These hard feelings are traceable to the past experiences of Podemos’ leaders in other organisations, notably United Left, which seem to have shaped the very essence of Podemos as a movement. Podemos, as a new way of doing politics, has been constructed, at least at the level of discourse, in opposition to all traditional parties, including United Left.

Image: Caricature of Pablo Iglesias and George Soros disseminated by Radical Left critics of Podemos. Allegedly, Soros had made positive comments about Iglesias. Source http://www.diario-octubre.com/2014/11/20/podemos-la-rueda-de-repuesto-del-capitalismo-voto-a-su-macho-alfa/

Image: Caricature of Pablo Iglesias and George Soros disseminated by Radical Left critics of Podemos. Allegedly, Soros had made positive comments about Iglesias. Source http://www.diario-octubre.com/2014/11/20/podemos-la-rueda-de-repuesto-del-capitalismo-voto-a-su-macho-alfa/

In my view, Podemos’ leaders must leave aside for good their emotional scars and frustrations accumulated over the years, which have not been helped by the vicious attacks that Iglesias has received from non-Podemos Left Wing activists and writers, who have portrayed Iglesias as the enemy of the Left, the spare tyre of capitalism and an alpha male of his own cult.

Apart from the criticisms of groups of activists who constitute the internal, yet relatively unorganised, opposition to Iglesias’ methods (not so much an opposition to him), there have been two notable internal responses to Iglesias’ rejection of the platforms:

The first came in the form of a manifesto called “Abriendo Podemos” (Opening Podemos), launched on 10 June 2015. It was signed by a group of prominent Podemos activists, including Pablo Echenique, former Podemos MEP and now MP for his region, Aragón.

Image: “Abriendo Podemos” (“Opening Podemos”) Logo. Source: www.abriendopodemos.org

Image: “Abriendo Podemos” (“Opening Podemos”) Logo. Source: www.abriendopodemos.org

In the manifesto, the signatories ask for the party to rethink its structure and give far more weight to the role of the Circles. They also vindicate elements of the more radical programme of Podemos, the one used in the European elections. The most well-known policy they proposed to rescue from that programme is a guaranteed citizens’ income (“renta básica”), which was downgraded in Podemos’ most recent manifestos to a form of tax credit.

The other internal response to Iglesias came from Juan Carlos Monedero, one of the founders of Podemos, number 3 until his resignation on 30 April 2015 and close friend of Iglesias. For Monedero, still a prominent Podemos activist, the solution is very simple: keep the name “Podemos” in the denomination of a new platform, adding to it, in a hyphenated formula, other word(s). For example (my example) “Podemos – Unidad” (We Can – Unity). This way, Podemos would provide for the name, the popularity and the methodology for the open selection of candidates and the elaboration of programmes, whilst allowing all sort of activists and members from other organisations to join this new space. Monedero’s proposal were been received with some degree of optimism by non-Podemos leading figures of the Radical Left.

However, Monedero’s preferred organisational methodologies are in flagrant contradiction with the formulae of Ahora Madrid and Barcelona en Comú. He is adamant that the General Elections cannot be won on the basis of fragmented popular assemblies in each one of the 50 provincial electoral constituencies of Spain. Monedero’s assertion should not come as a surprise. After all, some critics state that he had some responsibility in the diminished role of the so-called Circles, since he was Podemos’ secretary in charge of “Constituent Process”. Although Monedero reclaims a much closer contact of the Podemos’ leaders with the grassroots, maintaining the current decision-making procedures and the structure of his party remains for him an essential ingredient for success.

In his defence, Monedero would surely invoke the post-election situation in the city of Gijón, of around 300,000 inhabitants: In Gijón, the Podemos-backed open local platform “Sí se Puede Xixón” (“Yes, It Is Possible, Xijón), the third party of the city with 6 seats, saw how a local assembly of more than 3,500 decided on 11 June 2015, with an overwhelmingly majority, that their elected Podemos councillors should not offer their support to any other candidate to mayor but Podemos’. This decision prevented the PSOE, who had 7 seats, from reaching the necessary majority in the council. The city is again ruled by the Conservatives of the FAC, a spin-off of PP, who had 8 seats, to the surprise of many in the rest of Spain and probably to the embarrassment of most Podemos members. Local activists in Gijón claim that the financial scandal in which the PSOE candidate, allegedly, was involved was the reason behind this rejection. But the Gijón events must have helped to strengthen Podemos’ official line: in open platforms local people can feel empowered to challenge assumptions, strategic considerations and preferences of party leaders and committees. Certain types of popular power are difficult to harness when it comes to traditional state politics.

The challenge of popular platforms

Barcelona and Madrid provide good examples of how the Radical Left can find a structural and emotional solution to the challenge of different people from different organisations working together, but we need to understand that sometimes the main challenge for the platform comes from party-driven power-sharing discrepancies.

The platform “Cambiemos Murcia” (“Let’s Change Murcia”, Murcia is the 7th city in Spain with around 430,000 inhabitants) was acrimoniously abandoned by some of the Podemos members (of the Iglesias brand “Of Course We Can”) in order to form, in a hasty and dubious way, an alternative platform (officially created the day before the deadline for electoral registration of parties!) The rest of Podemos members of Cambiemos Murcia (belonging mainly to the critical sector of the party) remained loyal to the confluence process of the local Radical Left, which had been supported by the Podemos local assembly with 97% of votes in favour.

The official reason for this secession of “Of Course We Can” supporters was that Equo (Greens) had decided to leave the platform. The secessionists alleged that this had to be interpreted as an alteration of the substance of the coalition. In consequence, they could not feel bound anymore by the decision of the Podemos local assembly to pursue participation in the open electoral platform “Let’s Change Murcia”.

The most likely reason for this divisive manoeuvre, however, is that the “Of Course We Can” Podemos candidates had not managed to get the desired results in the open primaries. These had been dominated by United Left candidates, whose members apparently voted as a bloc. Despite the fact that Podemos candidates attracted more votes overall, their internal division played against their chances of occupying the top positions in the list.

Podemos’ internal conflicts commission (Comisión de Garantías) ruled against the officially backed perpetrators, but in such a mild way that even the candidate for the Regional Presidency of Murcia, also regional leader of “Of Course We Can”, felt legitimised to give public, enthusiastic and explicit support to the secessionist list in front Pablo Iglesias himself during a rally in Murcia City. Each one of the rival platforms obtained 3 seats and the new mayor of Murcia continues to be, albeit in a minority, a PP conservative.

Image: Cambiemos Murcia, the open popular unity platform of Murcia City challenged by the official Podemos tencency, “Of Course We Can”. Facebook profile picture of “Soy Cambiemos = Soy Podemos” (I am Cambiemos = I am Podemos”), a page for activists of Podemos who decided to stay in Cambiemos Murcia.

Image: Cambiemos Murcia, the open popular unity platform of Murcia City challenged by the official Podemos tencency, “Of Course We Can”. Facebook profile picture of “Soy Cambiemos = Soy Podemos” (I am Cambiemos = I am Podemos”), a page for activists of Podemos who decided to stay in Cambiemos Murcia.

Meanwhile, the other main party of the Radical Left, United Left, is undergoing a process of internal re-structuring resulting from their involvement in popular platforms. One of its main regional branches, Madrid, was formally dismissed from the party, wholesale, on 14 June 2015. This regional branch had confronted the state-wide executive ahead of the local and regional elections of 24 May when they refused to participate in the Ahora Madrid platform. The regional executive, supported by an important number of militants, rejected any dealings with Podemos and regarded themselves as the holders of the true values of United Left in the region. The critical sector of United Left Madrid followed the guidelines provided by the State-wide executive and integrated into the Ahora Madrid platform, whilst those loyal to the regional executive presented their own United Left list in Madrid city, which has been an electoral disaster, as they did not get a single seat in the Madrid Council.

Ethno-territorial diversity

When it comes to platforms, there is an extra layer of richness in Spanish politics: there are strong local political parties in some Autonomous Communities. This affects both the Right and the Left. The new vice-president of the Valencian Government, la Generalitat, Monica Oltra, from Compromís, the left-wing party that came 3rd in the 2015 Regional Elections in Valencia, stated after the election that her party would be happy to participate into a future platform for the autumn 2015 General Elections, providing that a) they keep their identity as a party inside the platform and b) that they can have a voice for themselves in the Spanish Parliament for issues concerning Valencia. Oltra is part of a new coalition government with PSOE in which Podemos was not inclined to participate. The option of a Podemos-Compromís for Valencia or a Podemos-Anova in Galicia is one that is being given more serious consideration within Podemos. Podemos-backed Platforms for the 2015 General Elections have much more chances to prosper in Autonomous Communities where there is a local powerful Radical Left Wing party.

The integration of local parties in State-wide coalitions presents greater challenges for the Left in Catalonia and the Basque Country than in other parts. The electoral clout of the pro-independence Left and Right parties in those two Communities makes the situation completely different to rest of Spain. The apparently peaceful relationship between Barcelona en Comú, supported by Podemos, and the other 3 main Left Wing Parties outside the Barcelona en Comú platform will be put to the test soon. The pro-independence movement “Procés Constituent” approved on the 13 June 2015 to create their own open platform in Catalonia for the Spanish General Elections in which they would like to integrate some of those parties, including Podem (Podemos in Catalan). The skills of Iglesias and his group to deal with sticky situations and “organise politics” will come handy when liaising with the possibility of Podem becoming a different party from Podemos. A relatively similar situation could develop in the Basque Country in the future, where pro-independence Radical Left Bildu is the second political force with 25% of the vote in the local elections and support for the right to self-determination, not necessarily leading to independence, is very high.

It is clear that for Podemos to be successful they have to represent the interests and concerns of the people of Autonomous Communities whose identities and politics are different to those of Castilian-speaking Spain. If a Radical Left government were to emerge from the 2015 General Elections, a constitutional reform, to adapt the Spanish State to its pluri-national make-up, would be the only option for those who believe that the Spanish State should remain united. One of the greatest spurs of the pro-independence Catalan movement has been the procrastinating head-in-the-sand policy of the Spanish Conservatives on the Catalan issue. My instinct tells me that Podemos will be able to persuade a majority of Basques and Catalans not to pursue full independence by taking the initiative in the question of constitutional reform in a brave, honest and sympathetic manner.

Activisms and identities

Podemos was immensely effective in co-opting many of the activists of the 15-M movement who did not have a party allegiance, plus some converts from other parties and some new blood. But now that the explosion of the 15-M Revolution is over, the growth of Podemos activism will come, at a steadier pace, exclusively from new militants, probably with little activist experience. Given the strong identity of Iglesias’ Podemos, defined partly in opposition to United Left and the traditional establishment parties, including PSOE, it is difficult to see activists from other parties simply joining the front line of Podemos, as members of the party, without a substantial change in the way the party is run and self-defined.

Additionally, group-based political identities in the Radical Left are deeply rooted into many activists’ personae (not so much into the voters’ political choice, as Podemos has successfully discovered). Surely any thoughtful activist who changes party out of her own accord would require a period of personal transition.

For the Radical Left to achieve a substantially better result than in May 2015, activism of the magnitude and richness seen in Madrid and Barcelona in preparation for the Local Elections is essential. The open platforms have proven to be the best catalyst, at this time in Spanish politics, for popular enthusiasm and empowerment.

In my view, the type of political change envisaged by the Radical Left requires activism. Contrary to what happens with the Right, activism is a cause of electoral success, and not simply a symptom of forthcoming electoral success. The Radical Left cannot rely simply on the complacency of voters, good TV appearances and spin doctors (Podemos are actually using the term “spin doctor”, literally, in English, to designate the job title of the two press officers of Pablo Iglesias).

Image: Pablo Echenique and Pablo Iglesias: event in Zaragoza. From Echenique’s Facebook page

Image: Pablo Echenique and Pablo Iglesias: event in Zaragoza. From Echenique’s Facebook page

Concluding thoughts on confluencia

United Left and probably Equo (Greens) are there to stay as parties because their activists want them to. The route followed by Anticapitalists (becoming an “association”) is not a suitable for them. Podemos cannot expect the leaders of these parties to call for their own dissolution for the greater good of an organisation that claims to be a Platform of Popular Unity but only allows individual membership. Podemos also cannot expect United Left leaders to be easily headhunted. Iglesias has said publicly that Alberto Garzón, the candidate for United Left, would be a great asset to Podemos. This created problems for Garzón himself within his organisation.

However, faced with the stubborn refusal of Iglesias and his group to create a Frente de Unidad Popular in which Podemos would be simply one of the players, the wiser move for United Left and Equo, if they want to increase the chances of a victory for the Radical Left in the General Elections, is to officially present their candidates, as independents, in the primaries of Podemos, yet maintaining their organisations as parties. This is perfectly acceptable in Podemos’ Statutes.

In return, “Of Course We Can” would have to ensure that their lists for the primaries are truly diverse. They would also have to revamp and democratise their methods of selection of candidates and define a formula of shared accountability for the elected candidates that come from non-Podemos parties.

Another essential measure for Podemos to become the electoral platform of the Radical Left would be to provide a truly independent and well-resourced internal conflicts commission (“Comisión de Garantías”) which can ensure that leaders and activists comply with the Statutes properly. Finally, the question of finance: Podemos should share any public funding and TV air time for elections stemming from the seats obtained by members of other organisations. As a result, United Left and other organisations would be able to continue to exist autonomously. In circumstances like these, unity is not about creative destruction but generous repurposing.

In the absence of a satisfactory deal between Podemos and United Left, a combination of non-Podemos activists and candidates, coming from United Left and other organisations, and Podemos’ internal opposition could still prepare their own lists and compete against the official lists of Podemos candidates in the primaries.

Image: “Desde abajo Podemos” (“Bottom-up We can”) event organised in Madrid by groups of Podemos activists who want to have more participatory grass-roots democracy

Image: “Desde abajo Podemos” (“Bottom-up We can”) event organised in Madrid by groups of Podemos activists who want to have more participatory grass-roots democracy

Meanwhile, the non-centralist Radical Left needs to actively build structures and spaces that are 1) flexible enough to accommodate old, new, explicit and implicit Radical Left identities and groups 2) innovative enough to enable the formation of new communities of practice where to learn, cultivate and develop the ways of participatory democracy beyond a centralising Podemos. The enthusiasm in Madrid and Barcelona prove the great appeal for activism of new open spaces. However, this should be seen as a plan that could only bear fruit, across the whole of Spain, in the medium to long term. Nobody would expect a Frente de Unidad Popular in such a short space of time to be fully operational and ready to compete not only against Iglesias’ Podemos, but also against the rest of the political forces across the spectrum in the forthcoming autumn 2015 General Election.

Podemos 2.0, which would include United Left in one way or another, is not that far away, perhaps under the name of “Podemos en Común”, but Podemos 3.0, the Podemos of the grassroots, needs time to brew.

Antonio Martínez-Arboleda was part of several internal electoral lists in Podemos in 2014 and 2015, runs various artistic platforms and is a lecturer at the University of Leeds.

1 comment

One response to “Podemos 2.0: The accelerated evolution of the Spanish radical left”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

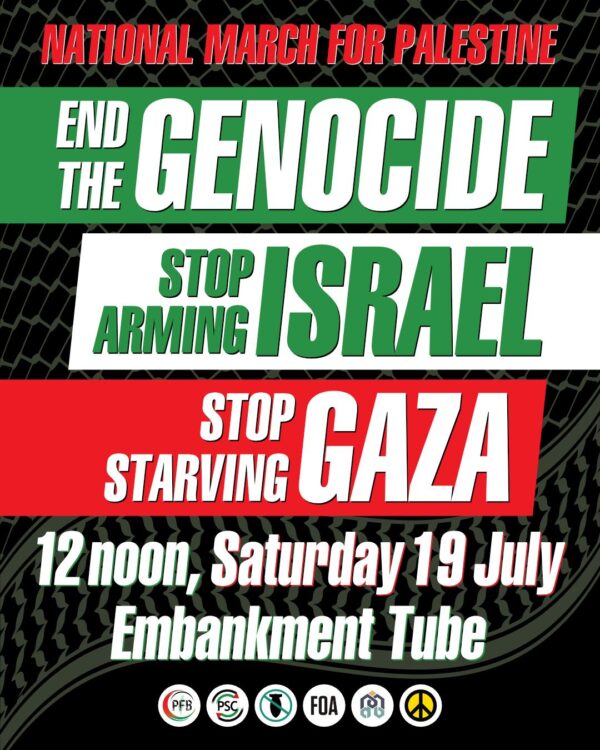

Saturday 19th July: End the Genocide – national march for Palestine

Join us to tell the government to end the genocide; stop arming Israel; and stop starving Gaza!

Summer University, 11-13 July, in Paris

Peace, planet, people: our common struggle

The EL’s annual summer university is taking place in Paris.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

I enjoyed reading this and I think it gives a pretty accurate picture of what has been happening in Podemos. It also correctly dampens over-excited illusions that Podemos will win the general elections in November. The article also raises lots of interesting and difficult questions that might face us in Britain if we can develop a Podemos or Syriza type alternative to Labour e.g. the internal structures that can guarantee democracy, the relationship between activism and insititutional representatives, how to do politics effectively in the media but also differently and so on. A useful source of articles on the Spanish state reflecting the views of the Anticapitalist current mentioned by the author is the Viento Sur website.