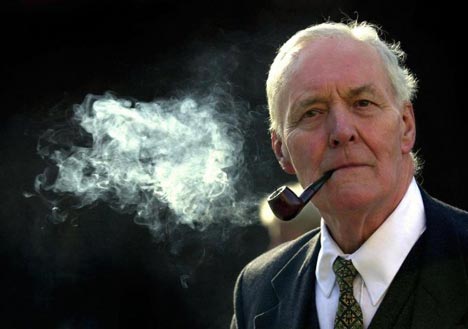

Tony Benn: a hero who encouraged us to be heroes too

I was sad to hear Tony Benn passed away this morning. When I interviewed him a few years ago, he spoke to me about his heroes. To so many on the left, Tony Benn was our hero and will be greatly missed. -Salman Shaheen

I was sad to hear Tony Benn passed away this morning. When I interviewed him a few years ago, he spoke to me about his heroes. To so many on the left, Tony Benn was our hero and will be greatly missed. -Salman Shaheen

To many of my generation, who were born in Thatcher’s Britain and whose politics were shaped by the stark reminder one morning in September 2001 that history was far from over, Tony Benn is a hero. It was another left-wing icon, Bob Dylan, who described a hero as “someone who understands the degree of responsibility that comes with his freedom.” And whether he’s speaking to two million people in Hyde Park on the largest demonstration in British history, to a packed out Left Field every year at Glastonbury, or to one interviewer, Tony Benn – a former cabinet minister under Wilson and Callaghan who retired from Parliament to “spend more time involved in politics” – has always known what that responsibility is. To inspire. Perhaps that’s too strong a term for a man of Benn’s unassuming humility. But to encourage? “If anybody asked me what I want on my gravestone, I would like ‘Tony Benn, he encouraged us’,” he once said. And in this dark climate, amidst war and recession, occupation, terrorism and environmental destruction, Tony Benn was kind enough to talk to me about the future of the Labour Party, about Afghanistan and Iraq – and to give me a few words of encouragement.

Benn has the distinction of being the second longest serving member of parliament in the history of the Labour Party. When he left parliament in 2001, Labour had never been more popular. Last month, at the [2009] European elections, the party suffered its worst defeat in almost a century. I ask Benn why he thinks it has lost so much of its support. “Well, the economic circumstances are very difficult,” he says. “A lot of people have lost their jobs and lost their homes, and they’re very, very worried and that always affects the government of the day.” But for Benn, it cannot simply be a factor of the accident of economics. “I think the policies that New Labour followed under Blair and Brown have made the situation worse, not better. We’ve had the Iraq war going on for years, now we have the Afghan war going on. Huge commitments to nuclear weapons that nobody wants, and ID cards and privatisation and so on. I think the policies of the government are very unpopular and I think for the first time in my life, the public is to the left of what is called the ‘Labour’ government.”

It comes as no surprise that Tony Benn is amongst the staunchest critics of New Labour’s move to the right. But even as Blair abandoned Clause IV and accepted the Bush doctrine, did Benn ever feel tempted to resign from the party? “No,” he says without a second’s hesitation. “I’ve lived so long, I’ve seen it happen before. In 1931, Ramsay MacDonald, one of the founders of the Labour Party, prime minister of a minority government, joined with the Tories and the Liberals, formed a national government and described the Labour Party as Bolshevism gone mad, there were only around 50 Labour MPs left, and 14 years later there was a landslide. So I think you have to take an historical perspective on it.” Benn describes the policies of New Labour as essentially Tory policies. “If Labour does badly in the general election, it will be a verdict on Blair and Thatcher together because those policies have been the same.”

Does that mean Benn thinks a defeat for Labour could bring the party back to the left? “I don’t think it’s a sort of ideological test,” he says. At this point he reels off the names of myriad micro-socialist parties that would be straight from satire if they did not exist. “It’s a sort of theological splintering where everybody seems to be more concerned to destroy each other than deal with the real problems. People look at politics to see if it actually helps meet their needs. They don’t want some ideological test. They want to know have we got jobs, have we got homes, good schools, health, medicines. That’s the way people see it.”

Benn has always been a rebel. From campaigning to be permitted to renounce his inherited peerage in 1963 to calling for the abolition of the monarchy in 1991 and for a mass campaign of civil disobedience on the outbreak of the Iraq war, if there’s a parapet, Tony Benn’s head is above it. It’s hardly surprising then, that as most young radicals find themselves growing more conservative with age, Benn has bucked that trend. “I’ve gone more to the left as I’ve got older,” he says. “And socialism explains the world. That doesn’t mean I’m trying to convert you or anybody else to my particular view of what socialism means. I think that’s the mistake that sectarians make.”

Benn does not know whether or not Labour will find a way to reconnect with its socialist roots. “I can’t forecast the future because it’s not my business,” he says. “My job is to try and influence the future.” Benn pauses after this wonderful soundbite as his mobile rings. “I go round the country,” he continues when the phone stops ringing, “I did eight public meetings last week, one yesterday, one today, another one tomorrow, another one on Sunday, and as I go round I’m pretty persuaded that the public is to the left of the Labour government. They don’t want the war, they don’t want the bomb, they don’t want ID cards, they don’t want privatisation, they do want civil liberties and so on. I think the system will have a chance of correcting itself provided we take up these causes and fight for them.”

The first time I heard Tony Benn speak, I was a sixteen-year-old A Level student taking up a cause and fighting for it. It was 2001, the twin towers had been reduced to rubble, Britain and America were bombing Afghanistan, the Northern Alliance had just forced the Taliban from Kabul – and Tony Benn was speaking to 100,000 people in Trafalgar Square who saw the way things were going and wanted to make a difference. I remain convinced that, although we could not stop either of the Bush-Blair wars, opposing them was the right thing to do. But whilst I have always advocated the immediate withdrawal of British and American troops from Iraq, the situation in Afghanistan seems to me more complex. I ask Benn if withdrawal is the right thing to do if it means leaving the Afghan people, after all they’ve been through since 1979, to the mercy of the Taliban?

“We didn’t go into Afghanistan because of the Taliban, we went in, we were told, because they wouldn’t hand over Osama bin Laden to the Americans after the Americans asserted that he was responsible for 9/11.” Once again, Benn is keen to take an historical perspective. “There’s a long history – we invaded Afghanistan in 1839, eighty years before I was born, and then we were driven out. We went in again in 1879 and had to withdraw. And we went in in 1919 after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The Russians went into Afghanistan and I led a delegation to see the Soviet ambassador in London and he said there were terrorists there. Who was he referring to? Osama bin Laden. And who was funding Osama bin Laden? President Bush’s father, the other President Bush.”

After one of the bloodiest weeks for British forces in Afghanistan, Gordon Brown argued that the campaign is a ‘patriotic duty’ to keep the streets of Britain safe. “I think it’s a complete fraud,” says Tony Benn, and there’s no doubt from the tone of his voice that he means it. “There weren’t any terrorist attacks in Britain until we invaded Afghanistan. None of the arguments are valid. It’s an unwinnable war. Every country has to work out its own internal problems. You can’t solve them with an invasion.” It’s a position to which he has remained consistent, despite his own political sympathies. “If we’d invaded South Africa to end Apartheid, there’d be bloodshed from that day to this.” But Benn is not a pacifist in the strictest sense of the word. “Everyone has the right to defend themselves. That is why the Afghans are absolutely entitled to defend themselves as their country is being invaded.”

Tony Benn once said that “all war represents a failure of diplomacy.” His own diplomacy saw him flying to Baghdad in February 2003, one month before the invasion of Iraq, to interview Saddam Hussein in an effort to prevent the war. But was the war ever Saddam’s to prevent? “No,” he says. “Bush had decided to invade Iraq and topple Saddam before 9/11. That came out quite clearly. And he told Blair that was his intention. And I think Blair said to him, ‘I could not persuade the British parliament to support an invasion on those grounds, so let’s pretend it’s about weapons of mass destruction.’ And Bush said ‘well it will take me months to get my troops there, so if you want to have a few months on the weapons inspection, then good luck to you.’ Hans Blix was sent in, totally ignored and frustrated. And I went to see Saddam; I said ‘do you have weapons of mass destruction?’ He said ‘no’. I didn’t know whether to believe him or not, but he was actually speaking the truth. He said he didn’t have links with al Qaeda, and I knew he didn’t, because Osama bin Laden called on the Iraqis to overthrow Saddam because he was a secularist.”

In that sense, the Iraq war was not a failure of diplomacy because there never was any diplomatic option. It’s an argument Tony Benn has made time and again from speaker’s podiums across the country. But with his son Hilary as a member of the Cabinet, who supported the invasion of Iraq, does he ever find himself having those arguments closer to home? “He has his position and I understand it. He knows my position.” Benn’s understandable reticence on the subject reminds me – just as the many Conservatives and Zionists I met at Cambridge whom I now count amongst my closest friends remind me, like his own friendship with Enoch Powell – that although the personal is so often the political, the political is not always the personal. And there is nothing that leads me to believe that he is anything other than deeply proud of his son’s achievements as Secretary of State for International Development under Tony Blair and Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs under Gordon Brown.

At 84, Tony Benn is a man who has been at the heart of many of the great political challenges of the last century. What does he consider to be the greatest challenge we face as we enter the next decade? “I think the economic crisis is a big one and it’s very linked to war because depression in the 1930s played a part in bringing the Second World War about. And there’s all the nonsense of religion being the cause of conflict, it’s not true at all, but they use it. There’s the threat of nuclear weapons, very, very dangerous. There’s the whole question of civil liberties, world population, environment. There’s a huge list of problems to tackle.”

Against such a huge list of problems, against all the odds, against all the setbacks the left has faced, the wars, the privatisations, Thatcher and Blair, what keeps Benn fighting? “I’ve been interested in politics since I was a child. I campaigned when I ten years old in the 1935 elections and I’ve still got some of the lists I pushed through the letterbox. I’m interested in it genuinely and I engage amongst communities, which is why I left parliament. I’ve got ten grandchildren and I worry about their future. I’ve written thirty-six letters to them and I’ve got a book being published in October called Letters to My Grandchildren.”

Tony Benn was elected president of Stop the War Coalition in 2004. Through his writing and his activism, through his speeches and his television appearances, and through the many thousands of people he has encouraged, he has undoubtedly accomplished much since leaving parliament. A 2007 poll by BBC2’s The Daily Politics declared him the UK’s ‘political hero’, narrowly beating Thatcher into second place. I ask him why, then, in the same year, he expressed an interest in standing again for Labour in Kensington at the next general election. “That’s not quite true,” he says. “After Brown became leader there was a rumour that we’d have an immediate election. We didn’t have a candidate here and I foolishly said to the local party, if you’re looking for somebody, I’m available. Thank God it never happened, the last thing I wanted to do was to go back into parliament.”

The reason for this is that Benn finds it easier to encourage an audience when he’s not asking them to vote for him. That’s the responsibility he has realised in his freedom from parliament. That’s what makes him, in Dylan’s terms, a hero. But who are Benn’s political heroes? “The three greatest moral leaders of my lifetime, all of whom I have met personally, not one of whom was white or European, were Gandhi, Mandela and Desmond Tutu. Gandhi against war, Mandela for civil resistance, Tutu, Truth and Reconciliation. Things that have been very, very relevant to our needs. Meeting them has been a special pleasure.”

And speaking to Tony Benn has been a special pleasure for me. It’s hard not to be impressed by his sincerity, by his integrity and by his passion. In a world where the star that burns brightest so often burns shortest, it is reassuring to see that Benn’s never dimmed. Not because he is a hero. But because, with his encouragement, we can all be heroes for more than just one day.

4 comments

4 responses to “Tony Benn: a hero who encouraged us to be heroes too”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

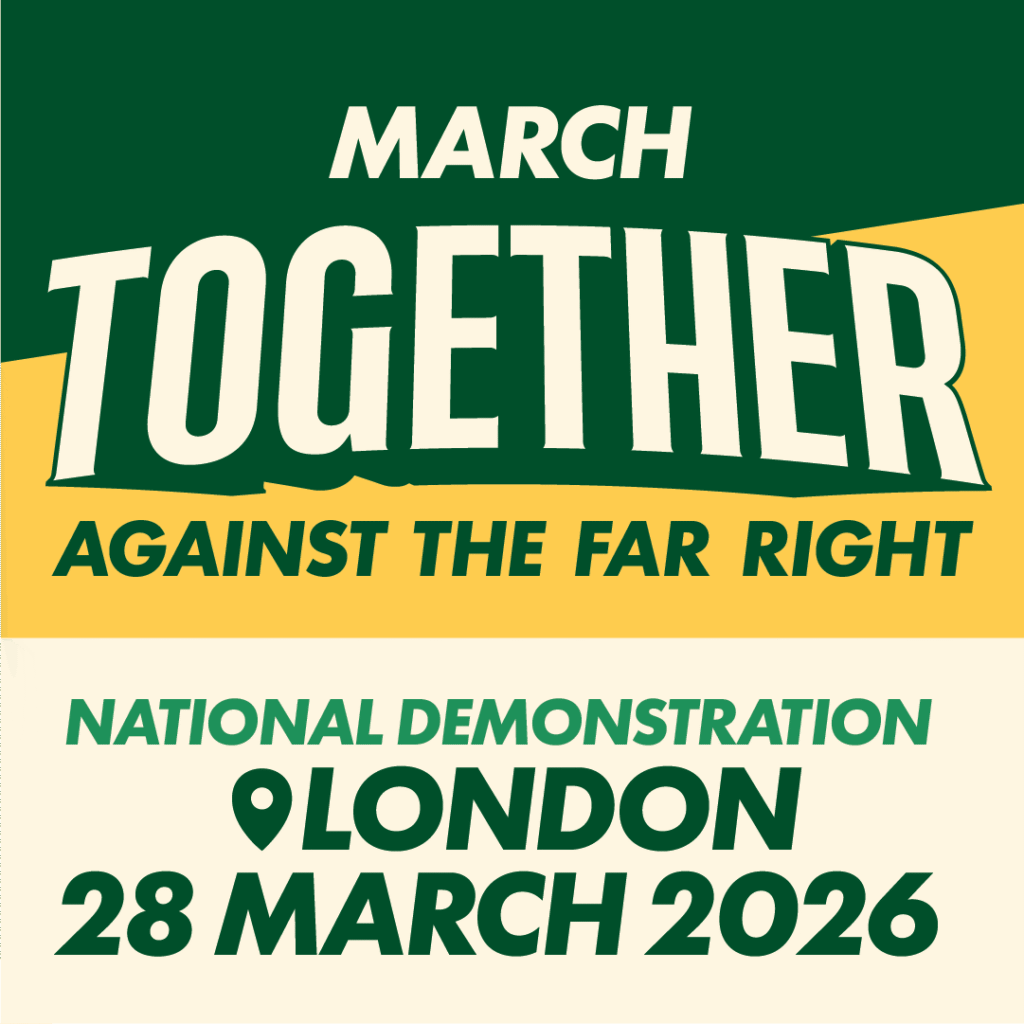

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

No mention of the word SOCIALISM in this article just as it is lacking in any obituary produced by much of the mainstream capitalist media primarily the BBC.

In the late seventies and throughout the eightiesWhile he had an incredibly strong influence on The Left and helped stimulate Socialist ideas within The Labour party and beyond, within the wider Socialist movement and Trade union movement.

His star duly waned over the last 20 years, mirroring the decline of The Left in Britain against the onslaught of neo liberal capitalism, such that he increasingly he became more a symbolic figurehead for The Left as The Left gradually ceased to provide the necessary new ideas and inspiration needed to renew hope and confidence in Socialist ideas and organisation.

Possibly the best thing Tony Benn could have ever done which he was never likely to do in recent times was to leave The Labour party.

Sticking with The Labour party (the fly on the ointment) through thick and thin during the New Labour era and beyond to the present day was simply part of the problem not part of the solution in my opinion.

By his own admittance he was never going to leave the Labour party and equally by his own admittance he saw himself that he was no longer dangerous or posed a threat to the establishment and ruling class.

His recent passing will touch the hearts of millions of people who knew Tony Benn to be a man of Socialist conviction in an ocean of vacant sound bites and a whole host of smarmy cynical corrupt neo liberal puppets otherwise known as politicians.

To what extent his reputation will be enduring and serve to further stimulate the in depth discussion and the vital renewal of some of his more radical and relevant Socialist ideas on democracy, economic and political, remains to be seen. It is perhaps up to Left Unity to take a lead in reinvigorating such Socialist ideas.

Tony Benn was a great man. However he and his supporters made a mistake staying in the Labour Party when new labour was set up .They should have broken away and formed a new socialist party.

Kevin O’Connor

Tony Benn was a man of great integrity, a gifted orator and a lifelong socialist. I feel privileged and honoured to have heard him speak and to have shared political ideas with him. For me, the Labour Party became a lost cause to socialists a long time ago but that didn’t stop me supporting and admiring Mr Benn. Now it is time to build a new force for the left: one that is truly democratic and socialist. For this reason I support Left Unity.

There is no question that Tony Benn was a man of great integrity, a gifted orator and a lifelong socialist. I feel privileged and honoured to have heard him speak and to have shared political ideas with him. For me, the Labour Party became a lost cause to socialists a long time ago but that didn’t stop me supporting and admiring Mr Benn. Now it is time to build a new force for the left: one that is truly democratic and socialist. For this reason I support Left Unity.