The Greek Debt Crisis and the Eurozone: A Beginner’s Guide

Left Unity principal speaker Pete Green writes.

Introduction: the Politics of Austerity

The election of the Syriza led government in Greece on January 25 was greeted with a wave of enthusiasm and hope across the European Union. Syriza had won the election on a programme which rejected what is known as the neo-liberal agenda, an agenda which involves cutting back the welfare state and deregulation (removing state controls over financial and other markets) supposedly with the aim of encouraging the growth of private companies and the economy. This agenda was what lay behind the conditions imposed on Greek governments under the Memoranda when they received seriously misnamed ‘rescue’ packages in 2010 and 2012.

The result in Greece had been a collapse in the size of the economy (measured usually by what’s called the Gross Domestic Product or GDP) of 25% accompanied by savage cuts in wages, pensions, healthcare and other benefits. Workers generally, along with the old and the unemployed were being made to pay for a financial crisis for which they were not responsible, and a debt from which they had derived little or no benefit even in the years of the Greek ‘boom’ in the early 2000s. That’s what the word “austerity” and phrases such as “tightening the belt” meant in practice.

The politics of austerity were of course imposed across the European Union. Workers in countries such as Britain and Germany have seen virtually no wage increases since the financial crisis exploded in 2008, and with prices rising have suffered cuts in their standard of living. Inequality between the richest 1% and the rest of us has been rising steeply for the last 30 years in all the richer countries of the global economy as exposed in the work of the French economist Piketty. But as in the past capitalist economic crises hit some national economies more severely than others. In the Great Depression of the early 1930s that included countries such as Germany and Austria, burdened with high debts dating back to their defeat in the First World War and the reparations (payments to the victors, especially France and Britain) imposed by the notorious Treaty of Versailles in 1919. German debts like those of Greece today proved to be unpayable and the Nazi government defaulted on them, refusing to pay after seizing power in 1933.

In the 1980s, Latin American countries such as Argentina, Brazil and Mexico were the biggest debtor economies and many countries in Africa and Asia were also crippled by excessive debt burdens. These were the countries in which the International Monetary Fund (the IMF, an institution set up in 1945 and funded mainly by the USA and the richest states in the global economy) first imposed its neo-liberal remedies with devastating consequences for much of their populations. The USA and other states used the IMF to rescue the American and European banks which had lent so much to these economies they were at risk of collapse, but they condemned the countries concerned to over a decade of negative growth or stagnation. In the crisis since 2008 the same remedies have been brutally imposed on the debtor economies within the Eurozone, especially Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain, whilst the priority once again has been to rescue the banks.

Austerity can breed reaction as well as resistance. In countries such as France it has led to the rise of far-right forces under the banner of the Front National which is hostile to the European Union on nationalist grounds. But the success of Syriza has inspired new movements and political parties from the left, and this is especially true in Spain where in recent elections coalitions of the left have made significant gains.

Precisely because of fear of this ‘political contagion’ effect, ruling elites across Europe reacted with scarcely concealed hostility to the new Syriza government. They were determined to refuse any concessions over the huge burden of Greek debt (which had risen to 180% of Gross Domestic Product or almost twice the size of the annual income of the Greek economy). They were scared that if Syriza could claim any sort of victory this would encourage more extensive resistance across Europe to demands for further austerity and the neo-liberal order which prevails in the European institutions.

Now, little more than six months on from the election, it is the Syriza government that has been forced to capitulate before the demands of its creditors, not least because of the threat of a collapse of the Greek banking system. We should not pretend that this is anything other than a serious defeat for the left not just in Greece but across Europe. However, the economic and political situation within the Eurozone area generally remains very unstable. Details of a new so-called bail-out have yet to be finalised. Targets have been set for Greece which are never going to be achieved. A leaked document revealed that even IMF economists consider that Greece’s debt burden is unsustainable and the IMF may refuse to participate in the process unless the Eurozone governments agree on significant ‘debt-relief’. As Daniel Munevar, an expert on debt issues from Colombia who worked as a close aide to Varafoukis until recently, comments in an article entitled ‘Why I’ve changed my mind about Grexit’:

“The problem is that these Memorandums are turning Greece into a debt colony: you’re basically creating a set of rules which, as the government misses its fiscal targets – knowing for a fact that it will – will force the government to keep retrenching even more, which will cause GDP to collapse even further, which will mean even more austerity etc. It’s a never-ending vicious circle.”

So the agony of the majority of the Greek people (excluding as one must the Greek oligarchs and their cronies who have their money stuffed outside the country) will continue and the political tensions will intensify. What follows can therefore only be a provisional assessment. But those who remain committed to solidarity with the Greek opposition to these measures need to avoid the simplistic narrative of betrayal being peddled by some on the far left. We need to recognise why Varafoukis, the now former Finance minister, summed up the situation facing the Syriza government in the Brussels summit on July 4 as a choice between ‘execution and capitulation’. But we also need to understand how the Syriza government ended up in such an impossible position, despite the 61% No to austerity vote in the referendum, and consider whether an alternative strategy was, or still is, possible. That requires that we step back from the immediate crisis and explore how the Eurozone works or rather fails to work, how Greece accumulated so much debt, and the role of the so-called Troika (the IMF, the European Central Bank and the Eurozone governments) responsible for imposing such harsh and punitive measures.

The Eurozone and the European Central Bank

The project to set up a single currency for the economies of Europe has a long history but in its current form dates back to an agreement between France and Germany in the early 1990s. France agreed to support the unification of West and East Germany and in exchange Germany agreed to the French proposals for a single currency. The advantage of this was that it would avoid the instability of separate exchange-rates going up and down (mostly down in the case of countries such as France and Italy). Large multinational corporations operating across Europe favoured the change as it would eliminate exchange-rate uncertainty and the costs of paying commissions when they changed from one currency to another. A timetable was agreed as part of the Maastricht treaty of 1992 from which Britain (along with Denmark and Sweden) opted out. The European central bank (ECB) and a virtual Euro were set up in 1999 but notes and coins in Euros did not appear until January 2001.

Greece was initially excluded on the grounds that its total debt level of around 100% of GDP was far too high and it did not meet the conditions for entry specified in the Maastricht Treaty. Despite this and following some financial trickery engineered by the US investment bank Goldman Sachs (for which they were rewarded with a huge fee of course) which enabled Greece to claim its debt was falling, it was eventually admitted in 2001 (with notes and coins from 2003). It is doubtful if many in Brussels were under any illusions about the reality of the Greek debt situation. As would occur repeatedly over the next decade the rules of the Treaty could be bent or ignored if Germany and France agreed on the political necessity for that.

The critical change for those countries that joined the new Eurozone was that they lost control over their monetary policy. The new ECB was supposed to be independent of governments and was run by a board of representatives from each national central bank plus the Governor and other top officials appointed by the European council of ministers. In truth these officials were almost all people who had themselves been bankers of one sort or another and their priority has always been to safeguard the interests of European banks and other financial institutions. The current governor, Mario Draghi, was once a vice-president of Goldman Sachs, which gives you a good idea of his priorities. Independence simply meant that they were removed from any form of democratic accountability to the people of Europe. That lack of accountability also applies to the independence of the Bank of England since 1997, pushed through by Gordon Brown and the new Labour government of the time.

The ECB is now responsible for both the creation of Euros (which are distributed via the national central banks) and lending to private banks across the Eurozone if they run short of funds. Individual banks can get into trouble because they lend out a large % of their deposits and that’s how they make a profit. Their role is supposedly to borrow short-term and lend for the longer-term. However, if too many depositors want their money back at once (as in Greece in recent months) a bank can quickly run out of available funds (this is called a liquidity crisis). One of the most important tasks of a central bank is normally to be the ‘lender of last resort’, providing funds directly to banks when such crises occur. This gives the central bank the power in effect to determine whether a bank that’s in trouble should be kept afloat or pushed into bankruptcy. If a bank is just short of cash because of excessive withdrawals the ECB will normally lend it money in exchange for collateral (such as property or government bonds owned by the bank which the ECB can claim if the bank fails).

However, if banks have lent too much to borrowers who cannot pay it back they are insolvent and may be forced to close. It was an insolvency crisis which affected many banks in the wake of the property crash of 2008/9 across much of the Eurozone. In this crisis the ECB expected national governments to decide whether to rescue their domestic banks as happened in Greece, Ireland, and Spain in particular at a huge cost, between 2008 and 2012.

This is a capitalist system in which as even Martin Wolf, lead commentator in the Financial Times, acknowledged, profits are privatised but the losses of the banks are socialised and of course this applied to Britain as well even though it’s not in the Eurozone. The socialisation requires that bank losses are taken on by governments adding to the fiscal deficits and national debt figures which are then used to justify ‘austerity’ measures inflicted on the mass of the population. First it seems we get ripped off by the banks with excessive fees, and interest payments. Then we have to pay for the speculative excesses of those same banks with cuts in welfare and higher taxes. This is a very sick system indeed.

Structural Flaws and Imbalances Within the Eurozone

The Eurozone is sometimes described as an instrument of German economic domination although there was more opposition within Germany to giving up the deutschmark than anywhere else in Europe (apart of course from Britain). Ruling elites feared that as the strongest economy Germany could end up paying the costs of supporting weaker economies or governments in trouble. They therefore insisted on various rules such as a limit on budget deficits (when government spending is greater than taxes) of 3% of GDP and the new, supposedly independent, ECB was prevented from lending money directly to governments. The first of these rules was broken by Germany itself along with France in 2002 and by many countries since, mainly because economic downturns or recessions always lead to a fall in tax revenue and higher public spending pushing up the deficit . The second has been broken since the Eurozone crisis of 2010 but remains a contentious issue especially within Germany.

Now, despite disquiet within Germany, the ECB is creating around a trillion in new euros under the deliberately opaque Quantitative Easing programme, a process which is no different in its effects from printing new money although these days they do it electronically. Much of that has been used to buy up bonds issued by governments in countries such as Portugal Spain and Italy, which would otherwise be vulnerable to the contagion effects of the Greek crisis as they were back in 2012. Back then the borrowing costs of those countries soared as they were seen as next in line for default. But in recent months their costs have barely shifted as the ECB has immediately plugged any gap in the market. However, in a blatantly discriminatory move, the ECB has so far refused to buy any bonds issued by the Greek government under this programme although they could easily buy up the whole of the outstanding Greek debt with what is in effect new money.

None of these rules addressed the fundamental problem of growing imbalances within the Eurozone as a whole. It is widely acknowledged, even in textbooks, that a single currency zone embracing a bunch of diverse economies as in the Euro case can only work under certain conditions. The most important of these (which do apply within national economies such as the USA and Britain) are:

1. There is mobility of labour so that if unemployment rises in one part of the zone workers can easily migrate to other areas where jobs are available.

2. Fiscal (ie Government spending) transfers can take place between strong and weak areas. This means for example that if some regions suffer from declining industries such as shipbuilding or steel they will receive subsidies towards their welfare spending, unemployment benefits etc from the wealthier regions.

3. The countries involved are convergent (coming closer together), in terms of their economic competitiveness usually measured by unit labour costs (wage costs including national insurance on average per unit of output).

The deep structural flaw of the Eurozone is quite simply that it does not meet any of these conditions in full. There is a provision for mobility of labour but this is much easier for younger and more educated workers, and language barriers remain an obstacle. The richer countries have refused to agree to any fiscal transfers to poorer countries except for the funds available for new entrants, which once benefited countries such as Greece and Ireland, but have now been cut back severely.

Most problematic of all is what’s known as divergence in the competitiveness of different economies. The Eurozone was supposed to promote convergence, bringing countries closer together in terms of economic conditions. What we’ve actually seen especially since 2008 is the opposite. A recent ebook available from Verso called “Against the Troika: Crisis and Austerity in the Eurozone” written by Heiner Flassbeck and Costas Lapavitsas (now a Syriza MP and member of its Left Platform) explains this in detail. Germany and other smaller countries in the core of the Eurozone were able to hold down the wages of their workers (especially since German unification in 1991) whilst their manufacturing industries have historically been much more productive. This has nothing to do with how hard workers work despite the myths. German workers work fewer hours and have longer holidays than workers in Greece or Portugal. The differences are a result historically of much more investment in advanced machinery, skills training and technical research in Germany in the decades after the Second World War. This was also the period when Germany benefited from American Marshall Aid and the cancellation of its old debts in 1953. The result, however, has been that countries such as Germany and the Netherlands have been able to build up very large trade surpluses not least by selling their goods to other countries within the Eurozone such as Greece and Spain. Some Germans may have opposed the Euro but German exporters benefited greatly, not least because the Euro was a weaker currency than the old deutschmark and therefore their exports were cheaper.

In the past weaker countries in the European Union (described by Flassbeck and Lapavitsas as the ‘periphery’) could devalue their currencies to improve their competitiveness, making their exports cheaper in other currencies. This was a short-term solution which also had the effect of raising the price of imports and therefore inflation. But exchange-rate changes could at least act as a sort of safety-valve and give governments more room to address the problems even if they didn’t always use that space effectively. Now that option has disappeared and for the countries such as Greece the Euro became overvalued or too high given their relative lack of competitiveness as measured by ‘unit labour costs’.

Instead what happened within the Eurozone was that growing trade deficits (imports minus exports) in the periphery were financed by capital inflows in the form of bank loans. This was much easier than before because the Eurozone single currency also introduced a ‘one-size-fits-all’ interest-rate set by the ECB. After the bursting of the dot.com bubble with falling stockmarkets in 2001, the ECB followed the US federal reserve in keeping interest-rates low. This enabled flows of cheap and easy credit which initially fuelled a boom but also had two consequences which soon led to disaster. On the one hand it encouraged private banks in countries such as Greece, Ireland and Spain to borrow huge amounts of money from banks in the core, with which they fuelled a boom in housing, and other speculative investments such as hotels. On the other it enabled governments in Greece, which had trouble collecting taxes especially from its wealthiest citizens, to borrow almost as cheaply as Germany for a short period. Where that money went is discussed in the next section.

The ECB and the Eurozone governments were quite happy to let this merry go round continue indefinitely as long as they could claim the single currency was a success. The financiers were mostly oblivious to the dangers (just as they were with subprime mortgages in the United States) as long as the short-term profits kept rolling in and multi-million euro bonuses were being paid out. But in 2008 the financial markets globally crashed in the wake of the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers in the USA. The Irish government had to rescue its banks which were also on the point of collapse, and this eventually required funds equivalent to over a quarter of the Irish economy. Suddenly the easy credit was no longer available. European governments deemed to be vulnerable by the financiers and credit rating agencies had to pay much higher interest rates to borrow at all. Greece would soon prove to be the most serious casualty of all within the Eurozone.

How Did Greece Pile Up So Much Debt?

In 2010 when the crisis in Greece was first exposed to the world, total Greek public debt amounted to roughly €300 billion or 130% of GDP. By the end of 2014 despite two so-called bailouts and a limited restructuring of the debt owed to private creditors in 2012, the total debt had risen to €318 billion and amounted to 177% of GDP. The rise in the % of GDP or the debt-ratio was mainly the effect of the 25% fall in the output of the economy, which resulted from the harsh conditions imposed on the Greek economy under the Memoranda accompanying the ‘bailouts’. Those conditions included savage cuts in government spending, wages and pensions, and tax rises which together resulted in the worst collapse in total demand and rise in unemployment (to almost 30% of the workforce in 2014) in the economy of any country in the Eurozone.

The analysis of the debt which follows are mainly taken from the preliminary report of the Truth Committee on Public Debt appointed by the Greek Parliament after the election in 2015. The Truth Committee was chaired by Eric Toussaint of the Campaign for the Abolition of Third World Debt (CADTM), who had previously been involved in debt audits in Latin American countries such as Ecuador. The report is only preliminary in part because the committee was denied access to certain documents by the ‘independent’ central Bank of Greece, which continued to follow the diktat of the ECB rather than the requests of an elected Greek Parliament.

Nevertheless the Truth Committee concluded on the available evidence that the Greek debt is ‘illegal, illegitimate and odious’. The legality issues refer to breaches of their own rules or constitutions by institutions such as the ECB, IMF and the Greek Government. The illegitimacy relates in particular to the breaches of human rights, such as the rights to basic sustenance, healthcare, and work, resulting from the conditions imposed since 2010. The word odious implies that the costs of repayment of the debt will fall on those, the poorest and most vulnerable in the society, who did not benefit from the original loans.

The public-sector debt rose in particular because of:

What the Truth Commission also reveals in detail is how the composition of the debt changed. This was a result of the two so-called ‘bailouts’ in 2010 and 2012. In reality it was the foreign banks that had lent money to Greece who were bailed out not the Greek economy. In December 2009 foreign bank exposure to Greece was €140 billion (36% owed to French banks and 21% to German banks). By December 2012 this had been reduced to €20 billion. French and German banks were even more exposed to other periphery country debt, especially in Spain and Italy, which were vulnerable to the contagion effect of a Greek bankruptcy and default. What happened instead was that almost all the new money provided by the ECB and Eurozone governments was used to buy up the Greek government bonds owned by their own banks. That money didn’t really go into Greece at all but was entered on the Greek government’s accounts. France and Germany only agreed to a ‘haircut’ (debt reduction) in 2012 after their own banks had succeeded in offloading most of the bonds in question. Greek banks and pension funds suffered most of the losses on the ‘haircut’ and they in turn had to be refinanced out of the new money lent by the Troika.

The share of Greek debt owed to the Troika institutions (the ECB, IMF and the special fund set up by the Eurozone governments called the EFSF) rose from 20% in 2009 to 80% in 2012. The share owed to private banks and other financial institutions fell from 80% to 20% and most of that is now held by banks and pension funds within Greece itself. An excellent article titled ‘A Pain in the Athens’ by Mark Blyth, in the Foreign Affairs journal, quotes former Bundesbank chief Karl Otto Pohl as admitting “the whole shebang was about protecting German banks but especially the French banks”. It is estimated that only 10% of the new money lent to Greece by the Troika has actually been available for spending by the Greek government. The rest has simply been used either to pay back existing debt or to rescue the Greek banks. That is also true of the latest bridging loan of around €7 billion provided following the acceptance of the terms of a new deal by the Syriza government. This will all be used to pay the money due to the IMF which the government had failed to pay in June and money due to the ECB in July and August.

If a new agreement is reached in the autumn it will be heralded as providing another €80 billion or so to Greece. This will be grotesquely misleading. Instead we will be witnessing another instalment of what Varafoukis described as the game of ‘extend and pretend’ or kicking the can down the road whilst the Greek economy fails to recover. Once again the new money will be used to pay back existing debts and cover the costs of pumping more funds into the Greek banks. One revealing feature of that situation is that the Greek Government owns the majority of the capital invested in the Greek banks in the form of non-voting shares which give it no say in how the Greek banks are run. Under the rules of the Eurozone the capital controls imposed on withdrawals etc were only introduced on the instructions of the ECB via the Greek central bank.

Why Did the Recent Negotiations Fail to Win Any Concessions from the Troika?

The most important factor in the situation facing the Syriza government since it was elected has been the power of the ECB to slowly strangle the Greek banking system. Almost immediately after the election it announced that it would no longer accept Greek government bonds as collateral for further loans to the Greek banks. That meant that the only funds available were provided via what is known as an Emergency Lending Facility which was operated on a drip drip basis from week to week as the Greek banks haemorrhaged money. Greeks who still had sizeable bank deposits were understandably made even more nervous by the possibility of the banks closing and withdrew as much as they could of their savings. The rich of course had already shifted their money outside the country into Swiss banks or other suitable tax havens.

When the referendum on the conditions demanded by the Troika was announced the ECB promptly responded by freezing its level of Emergency Lending, and thereby cutting off the Greek banks from any further funds and forcing the imposition of capital controls (the limits on how much Greeks could withdraw or transfer abroad). Despite all the denials this was a blatantly political move designed to frighten Greeks into voting no and the Greek government into further concessions. The majority of Greeks were still prepared to vote no to further austerity but the referendum result was simply irrelevant as far as the Troika were concerned. It soon became clear that the threat to force a collapse of the Greek banks was serious and the knock-on effects on the ability of firms to pay for imported goods in particular would be disastrous.

But why did the Troika institutions take such a hard line? After all it is now widely recognised that imposing further austerity on Greece is like bleeding a patient who has already been bled so much she’s on her deathbed. The IMF secret document says the debt burden is unsustainable and wants further reductions in the amount owed – although the IMF has also been very insistent on tough conditions for this, as it always has been in Latin America. Germany has opposed any cuts in the debt burden in part because it’s government is now the biggest creditor. Elements within the German government, represented by the finance minister Schauble, were also convinced that the programme won’t work but their alternative was to expel Greece from the Eurozone along with what Tariq Ali has claimed was an offer of €50 billion. But if Greece wanted to stay, Schauble was also insistent on tough conditions with monitors from the Troika acting as enforcers to prevent the slightest deviation of the Greek government from the terms of a new deal.

Predictably the Syriza negotiating strategy of seeking to divide the Eurozone governments and gain support from social democratic governments in France and Italy won nothing of substance. There was a split but only over whether Greece should be expelled from the Eurozone. Rightwing governments in Ireland and Spain were consistently opposed to any concessions which would encourage the growing movements against austerity in their own countries. So were governments in countries such as Finland which have suffered years of stagnation inside the Eurozone and seen the rise of strong Eurosceptic rightwing parties.

Most fundamentally what these events have conclusively shown is that all of these regimes remain committed to neoliberal policies in their own countries which impose the costs of financial crisis onto the masses whilst protecting the interests of bankers and oligarchs across the whole of the European Union. What scared them was the prospect that Syriza would become an example of resistance and a source of hope and inspiration to those fighting back across the rest of the EU. That’s what they set out to crush and, for the time being at least, they have succeeded.

We also need to recognise that we are still all living in a capitalist system in which creditors have always sought to exercise power over debtor economies. In the late 19th century British and French governments used that power to take control of Egypt and the Suez canal, and later to take over the running of the customs collection for the Ottoman empire. In several countries in Latin America such as Nicaragua and Haiti, the United States deployed gunboat diplomacy when debts were unpaid to impose dictators of its own choosing who could be relied on to repay loans and open up their economies to US investors and multinationals. In China in the final days of the Manchu emperors a consortium including the US, Britain and Germany also took direct control of customs revenue and sent in troops to crush the Boxer rebellion against the foreign devils.

Writing in the FT on August 2 historian Mark Mazower noted “A century or so ago, enforcement was easier because democracy was limited and public opinion could often be disregarded. In Egypt in 1882, default brought gunboats, the toppling of monarchs and military occupation. When Greece went bust in 1893, an international financial control commission took control of big revenue streams for decades and turned them over directly to the country’s bondholders. Greek public reaction hardly entered into the equation.” Yet, curiously, Mazower goes on to suggest that it’s different today.

More recently foreign debt crises across the ‘developing world’ from Latin America in the 1980s to East Asia in 1997/8 have been exploited by the USA and other creditor countries operating through institutions such as the IMF and World Bank to impose so-called structural adjustment policies. These were not just about the cuts and taxes designed to raise funds to repay the lenders. They were also about pushing through the politics of what is now known as neo-liberalism, forcing governments to open up their economies to foreign investors with deregulation of financial markets and privatisation of state-owned assets.

The parallel with the demands made by the Troika under the memoranda which Syriza was elected to resist are obvious. The conditions imposed under any new agreement will not just be about imposing austerity with higher taxes and more cuts in spending. The institutions want direct supervision of how and where the government spends its money. They have insisted on measures to prevent the restoration of collective bargaining rights to workers organised in trade unions. They have demanded more privatisation of government assets with the money to be placed into a fund controlled by appointees of the Troika. Those members of the Left Platform in Syriza who describe this regime as ‘neo-colonial’ are not exaggerating. Within the Eurozone the creditors don’t need gunboats to overthrow regimes or to force elected governments to capitulate. The power of the ECB to push an entire domestic banking system to the point of collapse is sufficient.

Is There An Alternative?

There are those who argue that Tsipras and his fellow negotiators had no choice but to accept the demands of the Troika. Certainly the threat of a collapse of the Greek banking system was very serious. The alternative according to Varafoukis who, however, voted No to the agreement, was ‘between execution and capitulation’. Yet Varafoukis himself apparently suggested emergency measures to introduce what’s called a parallel currency and take control of the Greek central bank, before he resigned immediately after the referendum in response to the Greek cabinet’s refusal to go down that route. The lesson of all this is clear at least to others on the left of Syriza. There is no way forward without an escape from the stranglehold exercised by the European Central bank over the Greek banks and the supply of euros (what’s called liquidity in the document below). Of course this could not happen successfully without extensive preparations. Flassbeck and Lapavitsas argue for a negotiated exit in their book Against the Troika and it is arguable that Schauble’s proposal of a five year Grexit should have been taken seriously.

If in Greece I would support the position taken by the representatives of the Left Platform within Syriza in the weeks after the referendum vote. I will therefore conclude with an extract from the Left Platform statement as translated by Stathis Kouvelakis, a member of the Syriza central committee based in London, for the Jacobin magazine on July 14 which can be found online (along with much other useful critical commentary not least in an interview with Kouvelakis himself)

‘In this critical moment, the Syriza government has no other choice than to reject the blackmail of the “institutions” who seek to impose an austerity program, deregulation, and privatization.

The government must declare to the “institutions” and to proclaim to the Greek people that, even at the last moment, without a positive compromise reflected in a program that will end austerity, provide sufficient liquidity to economy, lead to economic recovery, and include major writing-off of the debt, it is ready to follow an alternative progressive path which puts into question the presence of our country in the eurozone, while interrupting debt repayment.

In order to confront the pressures and unacceptable demands of the creditors, the process that could lead Greece out of the eurozone is a serious and complex enterprise, which should have been systematically prepared by the government and by Syriza. However, due to the tragic blockages that prevailed both in government and in the party, this has not been achieved.

Nevertheless, even now the government can and must respond to the blackmail of the “institutions” by posing the following alternative: either a program without any further austerity, providing liquidity, and leading to debt cancellation, or exit from the euro and default on the repayment of an unjust and unsustainable debt.

If required by the circumstances, the government has, even now, the possibility and the minimum of liquidity that is required to implement a transitional program to the national currency, which will allow it to implement its commitments towards the Greek people, and in particular to adopt the following measures:

1. The radical reorganization of the banking system, its nationalization under social control, and its reorientation towards growth.

2. The complete rejection of fiscal austerity (primary surpluses and balanced budgets) in order to effectively address the humanitarian crisis, cover social needs, reconstruct the social state, and take the economy out of the vicious circle of recession.

3. The implementation of the beginning procedures leading to exit from the euro and to the cancellation of the major part of the debt. There are absolutely manageable choices that can lead to a new economic model oriented towards production, growth, and the change in the social balance of forces to the benefit of the working class and the people.

The exit from the eurozone under present conditions is a difficult but feasible process that will allow the country to follow a different path, far away from the unacceptable programs included in the Juncker package.

We should emphasize that exiting the euro is not an end in itself, but the first step in a process of social change, of recovery of national sovereignty and of economic progress combining growth and social justice. It is part of an overall strategy based on productive reconstruction, the stimulation of investment, and the reconstitution of the welfare state and the rule of law.

In the face of the intransigent behavior of lenders, whose aim is to force the government of Syriza to full surrender, exiting the euro is a politically and ethically fair choice.

Exiting the euro is, finally, a path that includes confrontation with powerful domestic and foreign interests. That’s why the most important factor in addressing the difficulties that arise is the determination of Syriza to implement its program, drawing strength from popular support.

More specifically, some of the positive aspects of the exit include:

Recovery of monetary sovereignty, which automatically means regaining the capacity to provide liquidity to the economy. There is no other way to cut the European Central Bank’s noose on Greece. The elaboration of a development plan based on public investment, which will however also allow in parallel private investment. Greece needs a new and productive relationship between the public and private sectors to enter a path to sustainable development. The realization of this project will become possible once liquidity is reestablished, combined with national saving. Regaining control of the domestic market from imported products will revitalize and enhance the role of small and medium-sized enterprises, which remain the backbone of the Greek economy. At the same time exports will be stimulated by the introduction of a national currency. The state will be liberated from the stranglehold of the European Monetary Union at the level of fiscal and monetary policy. It will be able to achieve substantial lifting of austerity, without unreasonable restrictions on the provision of liquidity. This will also enable the state to adopt measures which will bring fiscal justice and redistribution of wealth and income. The possibility of accelerated growth after the initial difficult months. The resources that became inactive during the seven-year-long period of crisis can be quickly mobilized to reverse the disastrous policy of the memoranda, if there is sufficient liquidity and a stimulation of demand. This will open up the possibility of a systematic decline in unemployment and a rise in income.’

1 comment

One response to “The Greek Debt Crisis and the Eurozone: A Beginner’s Guide”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

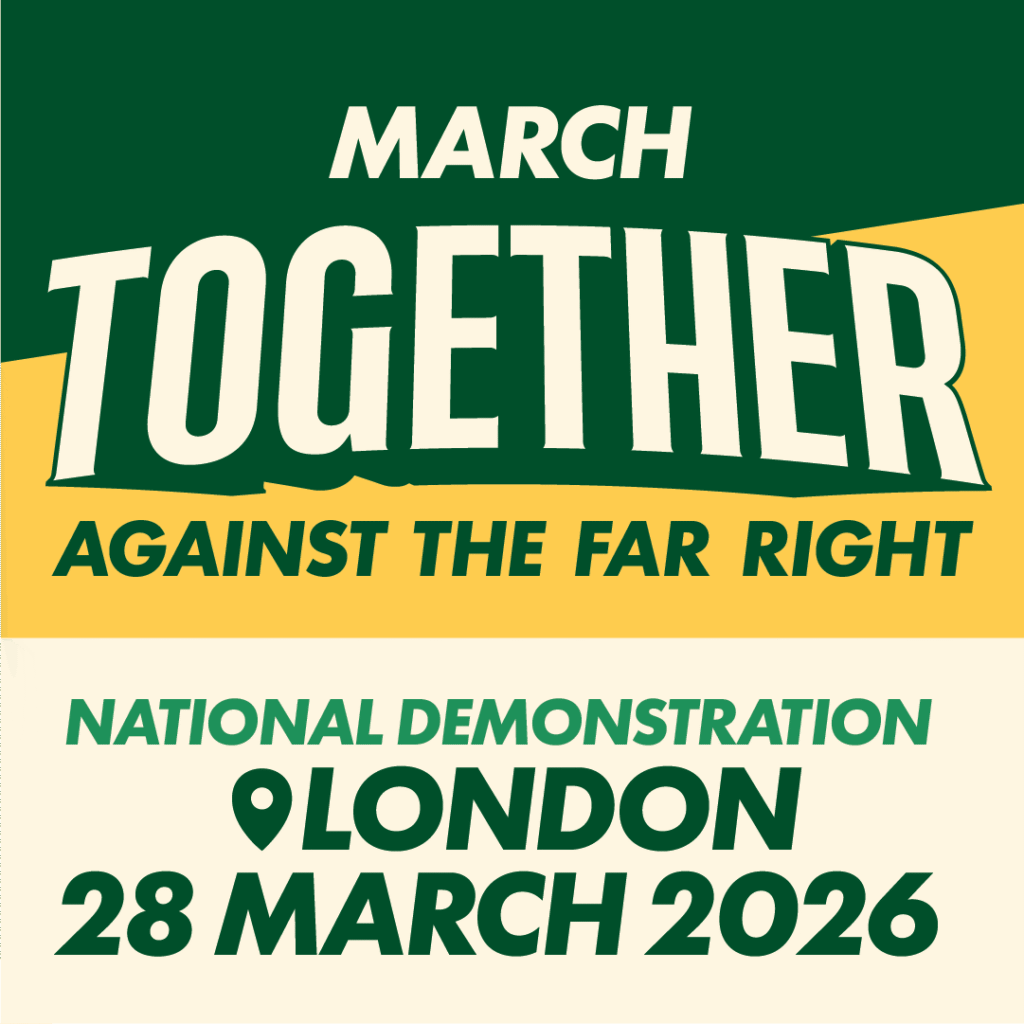

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Great explanatory article, Pete.

Missing from this, very useful explanation however is an analysis of the political/ideological roots of the total sell out perpetrated by the Tsipras leadership circle of Syriza.

Many of us on the radical Left (and everyone on the revolutionary/ultraleft and Stalinist KKE “Left) have long had severe doubts about the dominant Tsipras leadership circle’s willingness when push came to shove to build on the rising tide of radicalism of the Greek working class and its class allies as the last six months of fruitless negotiations with the Troika led inevitably to the political crossroads immediatey following the great “No vote” victory, ie, to press on to confront the Troika and its unreasonable , and economically suicidal, Austerity demands by pursuing a radical “Plan B” – or to capitulate. We know what the 21st century Ramsay Macdonald, Alex Tsipras’s choice was – complete capitulation – turning the radical Syriza government into an active collaborator with enforcing/administering ever greater Austerity and destruction of Greek sovereignty and sell off of national assets.

Why did Tspras and his circle choose the Ramsay Macdonald route of collaboration ? Put crudely , The Tsipras Circle all come from a background in either the corrupt “clientellist” politics of PASOK, or the equally dire political tradition of the stalinist Greek Communist Party. Both traditions have a deep contempt for self activity of the working class. For these political traditions the role of the working class is as a background cheerleading , but essentially passive, supporting chorus to the “real actors” – the political elite. The two traditions are also profoundly conservative – terrified of “unleashing the power of the working class for self emancipation”. This made it inevitable that the Tsipras circle would baulk at pursuing the radical Grexit “Plan B option – or even to put in place the structures and plans to make such an option a possibility.

It is not enough to merely recount the sheer weight of forces the capitalist powers brought to bear to crush Tsipras’s will to continue on a Left path. The roots of the Tsipras circle’s failure lies also within their own profoundly reformist politics. In this era of world capitalist crisis only a radical transformational socialist Left mass movement politically armed with the awareness that reform alone will not solve capitalism’s crisis , will meet the gravity of the task ahead for the Left in providing real uncompromising leadership .