The future economy of the UK

Sophie Katz on the future of the British economy.

(1)

If in depth attitude surveys in the UK are to be believed, most people think that the banks and bankers were responsible for the 2008 crisis. Beyond that, they also have had the opinion that up to 2008 the government spent too much – and that previous government overspending meant that there should be some cut backs. And despite hostility to the Coalition government, a majority actually seem to agree with their priority of cutting welfare. They are now parting company with the Coalition on the government’s favourable treatment of the rich, their unfavourable treatment of youth and increasingly, on cuts in wages and salaries. This growing concern is underpinned materially by the fact that 70% of the government’s reduction in spending so far has been drawn from spending cuts rather than tax rises.

Popular views are on a spectrum that includes those who are deeply aware of the massive shift of wealth that has already taken place away from those who are on benefits, those who are paid wages and even those who receive middle class salaries on the one hand, and of the contrasting and continued advance in the living standards of the wealthy on the other. But there are still a dwindling group at the other end of the spectrum who believe that society ‘deserves’ a dose of austerity to remove all our increasing dependence on debt.

In important respects the basic class-based facts of austerity Britain have got through to the population, despite official efforts to divert and confuse and scapegoat victims. We need to add to the picture however the general insecurity and alarm of the bulk of the population, which forms a backdrop to daily life, stemming as it does from a growing mistrust in our society’s institutions as well as doubts about the long term viability of the welfare state often projected as fear – of China and the east, of the EU and mostly of immigrants. Despite the fake ‘solutions’ that have emerged and that are being fostered by various agencies, the worries have a deep material basis.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, and including in socialist circles, there is a poorly developed, critical understanding of future prospects for the UK economy. Most progressive critics of austerity still rely on versions of Keynesianism as their alternative; they repeat the mantra of the need to stimulate growth and spending through state intervention. Why is the Keynesian cause significantly passed its sell by date as an answer to anything more than the shortest of short-term solutions for the UK economy? Why are the British population right to worry about the basic structure, most importantly the fundamental economic structure, of British society?

(2)

The economy is often separated off from the state and from political life (parties and governments) for the purposes of analysis. This perfectly legitimate analytical abstraction is helpful so long as we remember it has little to do with real life. One decisive element that it can often serve to obscure is the growing economic activity of the state itself, particularly in late capitalist countries. In Egypt, the army chiefs own Sharm El Sheik. In the UK the state will spend £720 billion this year. That amounts to the equivalent of 45% of all the identified economic activity in the country. (As a matter of interest £49 billion – 14.7% of the state’s spending – consists of the payment of debt interest. In large part this is the state is paying for the money it raised to save the banks.)

These facts panic right wing economists who are frightened by an ‘enlarging’ state and its ‘unprecedented’ debts. A recent Deloitte’s report for the Reform Foundation nervously writes that there has been a 17% increase in the proportion of GDP spent by government since 1963. ‘More profound changes (than the Coalition’s cuts) are crucial,’ it goes on, ‘to create the necessary impact on the UK’s balance sheet.’

From a socialist point of view there is no ultimately determining principle on the amount of the state’s economic activity in society – except that of its essentially subordinate role in serving and facilitating the lives of the majority. The economic place of the state in a socialist society should surely be a contingent one within a wider socialist perspective. (The state should enable the finding of solutions for issues such as how powerful big Capital remains and what concessions and or force are required to curb its power? What are the most desperate needs of the population? Which are the macro economic requirements to best serve the collective and popular endeavours to create new technology, new services and new ways of living?) In this new world the state begins to manage ‘things’ and not its own population – a population who are learning to manage themselves.

But in the here and now Deloitte’s and ‘Reform’s’ worries are based on more than ideological drama.

This year the UK state will raise £612 billion. It will spend £720 billion. (Remember – £49 billion of that is payment of debt interest.) The state in the UK gets most of its money from Income Tax, then VAT, then National Insurance. (£365 billion in total.) It spends most of its money on Welfare including Pensions, then Health and Education. (£454 billion.) Those three expenditures sum up in Britain what remains of the great advances made by the whole world’s working class following the victory against Fascism in WW2.

We should note however before going any further, that private capital has made massive inroads into Welfare, Pensions, Health and Education (WPH&E). Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) now take up over £20 billion of the value of WPH&E’s assets. Without any new PFIs these departments will still have to ‘pay back’ £119 billion to private owners for their PFI investments. In total the state owes £258.6 billion for PFIs already. (This is not part of the debt interest payments it has committed to.) PFI payments balloon over time and they are paid from the budgets of the services that use them. This year NHS payments alone for PFIs are £1.7 billion. They peak (if there are no further PFIs) in 2029/30 when the NHS will be paying £2.7 billion a year. A significant part of government expenditure in the WPH&E fields will therefore go to private sector profit over 30 years.

And the state’s income? The main sources of the state’s revenue are Income Tax, VAT and National Insurance. That basic pattern has remained relatively stable for the last 25 years. Before that Thatcher reduced corporation taxes dramatically (although they were never one of the top five sources of income) and profit has remained a relatively tiny revenue source since. What are significant are the changes that have been wreaked by both main parties within the top three taxes over the last 25 years. The process in Income Tax has been to ‘level it out.’ This means that a smaller and smaller number of tax levels has been introduced (apparently to ‘simplify’ the tax system) which has made UK Income Tax less and less progressive. Today UK Income Tax falls disproportionately heavily on below average and on average incomes. VAT is the big disaster for working class people. Despite a narrow range of exemptions, the tax’s conglomeration of all previous purchase taxes into one at a standard rate – and its relentless rise – means that whatever your income you are taxed the same as the rich for virtually all of your big purchases. And National Insurance on earnings has never been a progressive tax.

Deloitte and Reform say that the state will never be able to meet the burden of its debts unless it deeply reduces its remaining responsibilities in WPH&E. It is interesting to note that neither Deloitte nor Reform argue this case because we have an ageing population; nor that our workforce are not educated enough to produce more. (Although they do argue that productivity is low in the public sector, which is a staggering claim even in their own terms, as we shall see.) No. In fact the Deloitte paper goes so far as to spell out how Norway, Finland, Sweden and Denmark have all benefited from decades of a much more progressive tax structure and system and remain essentially stable today despite having the same demographics as the UK. But despite the strength of their case on the economic condition of Britain, Deloitte and Reform do not explain why the UK is facing the crisis of irreversible indebtedness that they insist it does.

In fact the UK’s current reality is a product of politico/economic decisions made on all our behalf’s by generations of the British capitalist class as it kept Imperial/Commonwealth Preference, beefed up the City of London instead of investing in production and technology, bolted on a welfare state to an already under-invested and decrepit capitalist model. It IS true those debts on government loans and on PFIs are already catastrophic. It IS true that the Keynesian mantra will not work in the medium to long term in Britain. Even the unlikely advent of a much faster rate of growth will not change the basic shape of this looming crisis for the state’s expenditure. The reality is that the banking crisis’s effects on the UK threw a penetrating spotlight on a system of capitalist relations and structures that are painfully and irredeemably unable to create new development for the people of this country – that are collapsing under the weight of their current domestic responsibilities – that have reached the end of the road even in their own terms.

(3)

Why were the utilities, coal, steel, transport etc., nationalised in Britain between 1945 and ’48? It was not as a result of the special conditions created by the war. It was because those great industries were dieing on their feet. Their owners had taken generations of profit and put in minimal investment domestically. They sought easy profits in India and the Middle East. Labour productivity in Britain therefore lagged behind all of its major competitors. Big Capital in Britain had been on a thirty-year strike. Today, British Capital is still on strike. British domestic productivity is among the lowest in the developed world. Capital ratios to labour in Britain are half of those found in Germany. Yet as £193 billion passed through the City in foreign and domestic investment in 2006, in 2011 private national and foreign investment in all of the rest of British industry was a total of only £120 billion (approx.) Yet Britain’s big Capital investors are epically rich in global terms. They have, lodged throughout the world (and not including a large part of the $13 to $20 Trillion worth of wealth held in tax havens – most of which are owned by Britain) a total of $1 trillion, 808 billion, in foreign investments. Britain’s big Capital investors ‘beat’ every country in the world except the US for foreign investment and account for over one sixteenth of the entire world’s foreign investment.

Chasing windfall profits across the globe, with a vastly overblown finance sector at home, domestic industry and manufacture starved of investment for a century, Britain’s capitalist system is totally unbalanced and increasingly unproductive for the British people. (An exception can still be made of the public sector whose 5.6 million employees’ productivity expands only, but directly, in line with any new investment – a sign both that need is currently greater than the resources provided and that public employees are efficient in that they directly increase productivity in line with the receipt of more resources.)

If Keynesian tinkering will not resolve the British mess, what is to be done? In the first place there are currently 14 different jurisdictions with some state control over economic affairs in Britain. These include the Northern Irish, Welsh and Scottish administrations, Local Councils and even the EU. Government constantly attempts to reorganise this picture mainly as a way of avoiding the elephant in the room – the actual structure of British capitalism. Currently much media, political and popular interest is being drummed up about the influence of the EU over Britain’s economics. Indeed Britain is strongly inserted inside the global economy. It is the main reason why the UK is buffeted so badly by any international economic stormy weather. The EU’s economics however are a separate case. The current crisis of the EU economy is largely a product of two engine rooms; the first being the tremendous over-strength of Germany’s domestic Capital formation, and the second the (increasingly negative) role of the City of London’s international finance and banking deals for Europe over the last 20 years. And it is a myth that any part of the most dynamic and invested part of British Capital – the City – is in any way subordinate to the EU. Equally the proportion of British Capital invested in the EU countries is relatively small. Removing the EU’s jurisdiction would certainly be a necessary part of a substantial programme of state and economic reform in Britain, but it is a long way from the top priority if our aim is to start with the thorough reorganisation Britain’s big Capital assets.

The main implication of any reform programme required to meet basic WPH&E needs in the UK and to make any future progress with national economic, technical and social development, given the crazy, over-extended and lopsided character of Britain’s Capital formation, is that it begins with the fundamental reform of Capital itself. This can only (as it was in 1945 – 48) be a conscious, that is to say political, act. No ‘self correcting’ mechanism is available to cure a disease that is proving terminal and has its roots in a century of evolution from Empire onwards. Gangrene has now set in at the root. The vast international holdings of British Capital both dominate and increasingly impoverish its domestic source. British big Capital has to be curbed and then thoroughly reorganised, from its foundations upwards, and subordinated to the requirements of the people of Britain and of the people of the poisoned world that it currently helps create.

(4)

Just as a state was required to ‘rescue’ the British banking system in 2008 – so a state will be necessary to reorganise and reconstruct the country’s capital assets. The creation of such a state would be a revolutionary moment in British history, the character of which belongs in the minds and the actions of millions of people with a just and essential cause. As nothing substantial can be consolidated overnight a series of transitional steps are indicated if we are to move in this direction.

A bold repudiation of all internal and external public debt as a single act – to wipe the slate clean – encouraging other beleaguered countries to do the same – would be a risky but unstoppable starting point.

At the same time all banks and finance houses would need to be socialised to retain assets and stop capital flow until these could be re-ordered more equitably.

A national bank would need to be consolidated from the other banks, to protect the currency and to create a vast new investment stream including a massive new house-building programme.

An audit of overseas assets would commence and a new punitive tax regime on such assets, holdings and wealth immediately initiated.

Income Tax would need to be revised to incorporate National Insurance and establish new grades up to a 75% tax on all incomes above £100k.

Law would introduce proportionality in earnings so that the highest earnings were no greater than 5 times the lowest.

WPH&E finances would be guaranteed in law to expand over inflation for five years.

Already totally dependent on state subsidy, and essential to future development, Transport and the Utilities would be taken into public ownership.

These initial steps and others open the way to breaking down the barriers to development and future progress currently in place as a result of the British Capital formation. They do not stand on their own. Such changes would need to march together with profound political adjustments; the removal of the House of Lords and the monarchy; getting out of NATO’s stranglehold on our defences and removing the EU’s rules on domestic economic management; most importantly of all, creating profound democratic structures that would be required to manage and control a new and free society.

NOTE

This is not a research piece. It is an argument. I have therefore not burdened the text with copious references. For those who wish to follow up the data, where its origins are not obvious, it comes from the following sources.

Deloitte – The State of the State, September 2013. Robert Taylor Think London Paper 2006. ONS Business Investment, 2012. OBR Economic and Fiscal Output, March 2012. Investing in Britain’s Future Pubs. GOVUK. CIA World Factbook 2012. Guardian Datablog 2012.

3 comments

3 responses to “The future economy of the UK”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

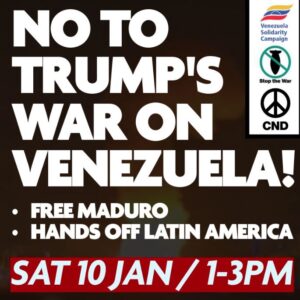

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Please have a look at my post on the Economy Commission board under “A New Pension System and Sovereign Wealth Fund” and download the attachment which sets out a detailed proposal.

Sophie,

Good article :-). My only critique is perhaps it could have been a little more concise in places.

On the conclusions though, i have a few points:

1. “repudiation of all internal and external public debt…” I think you would have to cap that e.g. to individual bondholder greater than £50k. Otherwise you will hit an awful lot of pensioners that have small scale bonds

6. “….highest earnings were no greater than 5 times the lowest.” That would need to be thought out properly. e.g. footballers have a career lifetime of only 15-20 years! So it can be argued they need to earn considerably more during their working years to make up for a long retirement. Likewise, if it takes 4 years of student debt + 6-8 years of subsistence living to become an academic, there needs to be some payback. I would argue that the multiple should start higher e.g. 10x and then brought down as other factors (e.g. student debt) start to get phased out.

7. “WPH&E finances would be guaranteed in law…” It is a dangerous thing to hand over politics to the judges. I would keep it as a policy to be implemented by LU rather than the legal system.

pps on references hyperlinking words in the text would have been fine.

A couple of people have asked me to enlarge on my comments about the economic dynamics of the EU. Germany fixes the Euro to mean that her goods are less expensive across her market in Europe and the City of London has organised the international loans which allowed Spain, Portugal, Greece, Ireland etc to buy German goods and maintain their domestic expenditure – given that these countries cannot devalue and force prices of imports up and buy less from abroad.