Spain’s left is rising

In a further advance for the European left, Spain’s Izquierda Unida (United Left) is rising in the opinion polls, as support declines for Spain’s major parties. Kate Hudson looks at the origins and development of Izquierda Unida (IU) and its relationship to PSOE – the social democrat-turned neo-liberal party comparable to Labour here in Britain.

In a further advance for the European left, Spain’s Izquierda Unida (United Left) is rising in the opinion polls, as support declines for Spain’s major parties. Kate Hudson looks at the origins and development of Izquierda Unida (IU) and its relationship to PSOE – the social democrat-turned neo-liberal party comparable to Labour here in Britain.

A recent survey conducted by Spanish newspaper El Pais, shows the conservative Partido Popular (PP) declining from 37.1% to 22.5% support over the past year while backing for Labour’s sister party, Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE) has declined from 25.9% to 20.2%. IU on the other hand – the Spanish counterpart of Syriza in Greece, Bloco in Portugal and Die Linke in Germany – has risen from 12% to 16.6%. This increasing popular approval results from its opposition to the devastating cuts taking place in Spain and the neo-liberal economic policies of both PP and PSOE. While not yet on the scale of support for Syriza, this development indicates a further blow to the dominant two-party pro-austerity model that afflicts Europe.

Although IU is probably less well-known in Britain than its political counterparts like Syriza or the French Front de Gauche, it was actually the first major manifestation of the left realignment which has emerged as the new European left over the past two decades. The Communist Party of Spain (PCE) had been legalised in 1977, following the end of the Franco dictatorship, during which it had been the most effective and organised opposition force, winning undoubted prestige for its courage. But it was unable to translate this prestige into electoral support and had swung to the right under the leadership of Santiago Carrillo. He embraced the new liberal democracy in Spain and did not press for concessions to the labour movement, rather accepting the restoration of the monarchy and supporting restrictive trade union legislation. He espoused Eurocommunism which caused splits within the party, many of whom considered his concessions to the bourgeoisie – in the form of cooperation with the conservative government of Adolfo Suarez – as treasonous.

The PSOE under Gonzalez, which received funding from the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the Socialist International during the 1970s, was initially able to position itself as a more radical and popular force, winning around three times as many votes as the PCE in general elections in 1977 and 1979. One of the oldest parties in Spain, PSOE was founded in 1879 as a party to represent the industrial workers and had a strong radical and Marxist tradition within it. It was banned by Franco in 1939, persecuted during the dictatorship and legalised in 1977. Despite its radical credentials, however, its leader Felipe Gonzalez, from the more reformist wing of the party, worked to break PSOE from its Marxist heritage and orientate towards a more mainstream form of social democracy, supported by other west European parties. Despite opposition and division within the party, Gonzalez was successful in this goal, and by the end of 1979, the party had broken with Marxism.

The disintegration of the right led to a PSOE victory in the 1982 elections, winning 46.1% of the vote, gaining an absolute majority in parliament. According to Donald Sassoon, PSOE was elected, ‘to modernise the country, solve the economic problems and establish a welfare state’.[i] With the PCE in crisis and winning only 4% of the vote, PSOE no longer ran the risk of being outflanked on its left and became one of the first socialist parties to embrace neo-liberalism. In government it prioritised reducing inflation which was paid for by a rise in unemployment from 17% in 1982 to 22% in 1986.

This early shift to the right of the Spanish socialists in government created the political space for a left to emerge which would oppose PSOE’s anti-working class policies. After its electoral disaster in 1982, the significant political divisions which existed within the PCE were forced out into the open, particularly against the rightist line pursued by Carrillo in the late 1970s. There were two main groupings within the party that opposed him. The first was a straightforward right-left split over the political direction of the party over Eurocommunism and attitudes towards the Soviet Union. The second was based on the rejection of Carrillo’s authoritarian style of leadership and comprised a group of renovadores (renovators) who agreed with his political orientation but wished to democratize the party. Opposed from all sides, Carrillo stood down in favour of Gerardo Iglesias.

The PCE then went through a process of splits which subsequent developments in many west European communist parties were to closely mirror. Carrillo left to form his own group which became the Spanish Labour Party, received virtually no popular support, and eventually joined PSOE in 1991. Thus Carrillo moved to the right, through Eurocommunism to social democracy, like the majority of the Italian Communist Party with which he had close links in the 1970s. Carrillo made his position completely clear in September 1991, saying: ‘the Communist movement as such has completed its historical cycle and it makes no sense trying to prolong it.’[ii]

Two other organisations emerged out of the PCE crisis: to the left, a pro-Soviet split, the Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain (PCPE) under the leadership of Ignacio Gallego, and to the right, the Progressive Federation (FP), a group of renovadores under the leadership of Ramon Tamames. As a result of these splits, the PCE was more politically homogeneous than before, but in urgent need of re-establishing its political role in Spanish society.

From 1984, the PCE advocated a process of convergence with other left forces, to fill the political space opened by the rightwards move of PSOE but the real opportunity to bring this about came as a result of PSOE’s U-turn on NATO membership. Shortly before the 1986 general election the PCE put together a coalition called the United Left (IU), born out of a mass campaign during the first PSOE government on NATO membership. Before entering government, PSOE had opposed NATO membership and had promised a referendum on membership, changing its position when in government. A broad committee, including communists, pacifists, feminists, human rights groups, Christians and the far left – with the exception of Carrillo’s group which refused to participate – coordinated a vigorous campaign, which in spite of media saturation and huge pressure for a ‘yes’ vote, actually won 43% of the vote – nearly seven million – against NATO. Criticism was levelled at the government’s phrasing of the referendum question, which asked, ‘Do you consider it advisable for Spain to remain in the Atlantic Alliance?’ followed by a number of provisos, including the lessening of US military presence in Spain.[iii]

The term NATO was not used. One of the key leaders of PSOE at this time was Javier Solana, who went on to be Secretary General of NATO in 1995. It was this anti-NATO campaign which provided the basis for the founding of the IU in 1986. The main components of the IU were the PCE, the PCPE, the Socialist Action Party (PASOC) – left dissidents from PSOE, the Republican Left (IR) and some smaller left groupings, subsequently including members of the Trotskyist Fourth International. Although it initially made little advance on the PCE’s result of 1982, it remained the foundation for the IU’s relaunch in February 1989 and a more than doubling of its votes in the general election of October 1989 with 9.1% of the vote. According to Gillespie, it ‘provided the major success story of the general election’.[iv] By the general election of 1996, its support had risen to 10.5% taking 21 seats.

However, the right wing Popular Party (PP), of Jose Maria Aznar, defeated the ruling Socialists (PSOE) by 38.8% to 37.6%. This defeat, which led to the first right-wing government in Spain since 1982, provoked a crisis within the IU about its relations with PSOE, particularly regarding its policy of ‘sorpasso’ – overtaking PSOE – which had led both to hostility towards PSOE and to political attacks upon it, which may well have contributed to its defeat. The debates focussed on the basis on which alliances with PSOE might be forged. A minority within IU, which had previously supported the Maastricht Treaty, argued for alliance with PSOE without pressing for any political change. The leadership position was that it was not in principle opposed to forging an alliance with PSOE to form a new left majority, but the alliance had to be on the right political terms. The IU leadership wished to use an alliance to push PSOE to the left and on this basis, IU went into the 2000 general election having signed an agreement with PSOE but both parties did very badly – PSOE on 34.16% and IU on 5.45%. Aznar’s PP was again victorious with 44.52% of the vote. As Luis Ramiro-Fernandez observed, writing prior to the 2004 election, ‘The competition for left-wing votes is nowadays more difficult, since the Socialists are in opposition to the centre-right government. Somemessages of IU’s discourse are likely to be adopted by its main competitor.’[v]

In fact, there were two particular factors which led to a victory for PSOE over the PP in 2004. Firstly, the opposition of PSOE’s leader Zapatero to the Iraq war, which had been backed by Aznar. According to Joan Guitart, ‘When on March 16 Aznar joined the “Azores three” alongside Bush and Blair, a month after the huge mobilisations of February 15 against the war, the rejection was very large, but it expressed more a “public opinion” than a social movement. In these conditions, it was easy for the PSOE to be its “political expression” and the withdrawal of Spanish troops from Iraq became the major issue for Zapatero at the general elections of March 2004.’[vi]

Secondly the way in which the PP had tried to manipulate the tragic Madrid Bombings – which took place three days before the election – to their own ends. PP claimed it was an ETA bombing when in fact evidence suggested it was a militant Islamic attack, possibly linked to the Spanish government’s backing for the Iraq war. The result was that PSOE polled 43.3%, PP took 38.3% and IU 4.96. Zapatero proceeded to form a minority government and both IU and the Republican Left of Catalonia gave their backing, giving Zapatero’s government an effective majority. PSOE won again in 2008, whilst IU, in coalition with Initiative for Catalonia-Greens (IC-V), lost three of its seats, now reduced to 2 seats and 3.77% of the vote.

Under its new leader, Cayo Lara Moya, elected in 2008 after the election disaster, IU has pursued a path that is strongly critical of the measures taken by the PSOE government to deal with the economic crisis – massive public spending cuts having a devastating impact on the living standards of working people and the increasing number of unemployed. As Cayo Lara stated on 31 December 2010, ‘The PP and PSOE defend the same neoliberal model. Posing a left alternative to the savage neoliberalism is the task that lies ahead.’[vii]

It is this opposition to the economic policies of both PP and PSOE – and the posing of a left alternative – which accounts for the increasing support for IU. There is no doubt that Labour in Britain has now moved rightwards in the same way as PSOE. Unlike Spain, however, we do not yet have a mass party to occupy the left space which it has vacated and to pose the urgently needed political and economic alternatives. I urge all those who would like to help found and build a new left party in Britain, to get involved in Left Unity. Why should we go without?

[i] D. Sassoon, One Hundred Years of Socialism (London: I.B. Tauris, 1995), p.627.

[ii] J. Amodia, ‘Requiem for the Spanish Communist Party’, in D.S. Bell (ed.), West European Communists and the Collapse of Communism (Oxford: Berg, 1993) pp.117-18.

[iii] http://emperors-clothes.com/articles/javier/solnato.htm (accessed 15 January 2011).

[iv] R.Gillespie (1990) ‘Realignment on the Spanish Left’, Journal of Communist Studies, 6 (3), p.119.

[v] Luis Ramiro-Fernandez, (2004) ‘Electoral Competition, Organizational Constraints and Party Change: The Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and United Left (IU), 1986-2000’, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, 20, (2), p. 25.

[vi] http://www.internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article1508&var_recherche=izquierda%20unida (accessed 6/1/11)

[vii] http://www.izquierda-unida.es/node/8156 (accessed 6/1/11)

8 comments

8 responses to “Spain’s left is rising”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

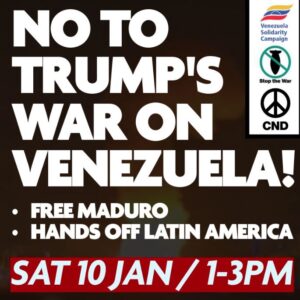

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Sorry but to have an article on Leftward shifts in Spain and not mention the massive social movments (such as the indignados) that have dominated Spainish politics over the last few years is simply delusional. Indeed it was the activists and networks of the alter-globalisation movement that sparked the huge demoinstrations after the Madrid bombing and changed the direction of the subsequent election. Social movements are the force that can alter the poltical discussion and change the way people think about the world – it is this that allows changes in patterns of parliamentary voting but more importantly opens up the possibility for more fundamental change.

It may well be necessary to rethink the relation between electorally focussed political Parties and social movements (which in recent times have been generally suspicions of parliamentary politics – Eg Real Democracy Now!). The fear is that any turn to parliamentary politics will elide social movements just as this article does. We need to turn our usual way of thinking on its head and ask what a Party focussed on elections can do for social movements and not the other way around.

Hi Kier. I don’t think it’s delusional. It’s just an article on Izquierda Unida as it very clearly says in the first sentence. I certainly recognise and strongly support the massive social movements in Spain and their role in fighting for change. But I am not knowledgeable enough about them to write in detail. It would be great if someone from the movements in Spain, or someone with contacts there, could write an article/s about them for this website. There have been a number of other pieces on this site about Spain, especially anti-austerity protests both small and large. They can be found under the international tab on the home page, listed under Europe, then Spain.

Spain’s left is indeed on the rise, as Kate says. IU has been moving up steadily in the opinion polls since the 2007 general election when it got just under 7 per cent. In fact I got a mail from a friend in Barcelona today saying that in one recent poll IU came in at 19 per cent. The poll results have been replicated by the advances made by IU in several regional elections. And this is against a background of continuing mobilizations against austerity.

It is significant that PSOE, far from benefiting from the discredit of the PP government, has been dropping in the polls at about the same speed. It is now quite possible that IU will overtake it. That would be a major political upset. The Spanish political system, like others in Europe, is based on alternating governments of centre-left and centre-right, pursuing the same neo-liberal policies. Syriza was the first to break that, maybe IU will be next.

Interesting article Kate.Thanks

In the light of discussions at out recent meeting could you shed some light on how IU is organised internally. Did all the component parts you listed merge properly into a OMOV party?

Hi Kate

Thanks for a very informative article.

In light of some recent discussions taking place in Left Unity it was good to read your mention of the importance in Spain of left groups (in particular the Communist Party of Spain) being an integral part of setting up IU in spain.

Lee

Yes, an interesting article, Kate. However, It is always tempting to suggest non-existent parallels between political developments in societies/states with radically different histories and political structures and traditions . We aint Greece, (or Spain) and Left Unity wont be built from the same historio-political components as Syriza

One absolutely critical aspect which radically differentiates the UK from most other European nations (particularly Greece) is the lack of a truly mass Communist Party at any time in our history – even including its relatively large WWII wartime/immediate postwar size. This is important in Left Unity’s case for a number of reasons. Firstly the total membership of the groups today with direct historical connections to the old CPGB , is absolutely tiny – far smaller than the total membership of groups from the Trotskyist or Anarchist/Libertarian traditions. This is very unusual in European terms. It means that the ” neo-Communist” Left has nowadays few membership resources , and little real remaining influence in the trades unions, to “bring to the party” (pun intended).

Secondly, it also means that it is the “anti-Stalinist” traditions and (competing) negative views of the past and few remaining, “socialist” (ie, “Communist”) states that dominates the entire “Left” in the UK . There is absolutely NO significant sentimental attachment or admiration in UK society for the old Soviet Union or its satellites. In fact the overwhelming majority of people likely to be recruitable by a radical Left party committed to fighting the Austerity Offensive view the entire “Socialist States” (ie, totalitarian Stalinist) experience with utter distaste and horror.

Yet here we are, about to embark on yet another radical Left party building exercise , and the LU discussion forum is spattered here and there with open or partly concealed inferred praise and enthusiasm for the “achievements” of the Soviet Union. If Left Unity is to have ANY chance of building a mass-based democratic radical Left party in the UK it will have to make very clear in its eventual “What We Stand For” statement and in its contemporary international analysis that we are a radical party of Democratic Socialism, with no illusions about the gross nature of the monstrous tyrannies that the Soviet Bloc and other supposed “socialist/communist” or “socialistic” social models represented to their own working classes. One official statement of support from LU for the likes of murderous totalitarian dictatorships of the Gaddafi or Syrian , or North Korean, ilk, and we are dead in the water as a credible party as far as the general public are concerned.

If we fail to make this quite clear, we may well recruit a tiny handful of sentimental/delusional neo-Stalinists, and maybe a few equally deluded Trots who still think nationalised property in itself represents a progressive leap forward to some sort of “workers state”. But the capitalist press and our Labour Party rivals, as well as the other capitalist parties, will make ideological mincemeat of us. For the radical Left the now universally known ghastly historical experience of totalitarian “communism” is equally as great a potential barrier to real mass growth as is Nazi history to the growth of neo-fascist parties like the BNP, in the UK context.

We have to break openly and cleanly from any connection between our political aims and this history of murderous tyranny and failure if we are to have any chance of building an attractive mass radical Left Party. Fail to deal with this issue resolutely, eg, mimic the fascist “holocaust deniers” strategy , by simply denying the monstrous crimes of stalinism as “propaganda”, or even actually endorse and praise the past “communist” regimes, and it is an unexploded “political landmine” in the path of the new Party, just waiting for the capitalist press and the other parties to ignite it when convenient.

John

Absolutely – spot on.

In other words, do like Syriza, Front de gauche, Izquierda Unida, etc.:

http://youtu.be/qYSJpnU6TUc?t=8m9s