Socialism, Democracy, and the Break-up of Britain

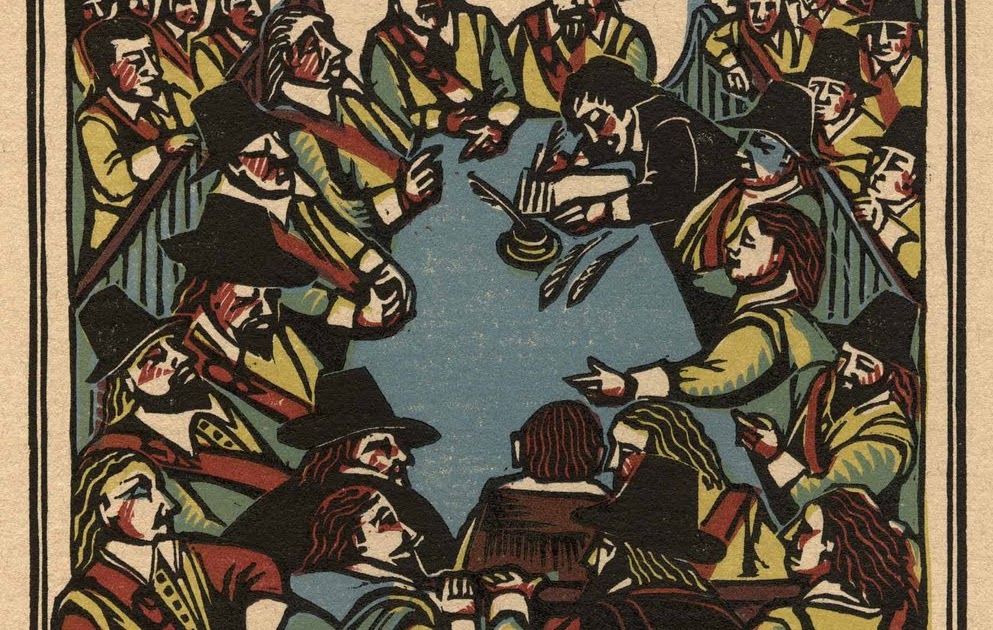

Putney Debates

Len Arthur and Craig Lewis write: This article is a contribution to the on-going debate in Left Unity concerning socialism, democracy and how socialists should relate to independence movements. It is a timely debate, given that even English liberal commentators appear to have woken up to the potential break-up of Britain (England and the Union: We need to Talk: Guardian editorial 2 July 2021).

The first part addresses the importance of linking democratic and eco-socialist demands and actions into a coherent transitional approach to a socialist future. It outlines how we have tried to put this into practice in our engagement with the independence movement in Wales. The second part looks more specifically at the question of nationalism. In doing so it tries to address some of the important questions raised in David Landau’s recent contribution to this debate. It also develops the significance of including a democratic “republicanism from below” approach in our transitional programme of demands and actions.

1.Socialism and democracy are inextricably linked

‘Radical measures are necessary to ensure a transformation in the economic structure and a reversal of this damage. Our goal is to transform society: to achieve the full democratisation of state and political institutions, society and the economy, by and for the people.’ About Left Unity from the website.

Given such a strong statement from our basic principles document it is surprising that there is some questioning about the relationship between democracy and socialism and that the two aims might not be inextricably linked: how else could planned production be orientated from profit to the needs of people and the planet if those who have the needs do not exercise democratic control over the planners? How else do we decide on the application of the principle ‘from each according to their ability to each according to their needs’ if not through the operation of workers’ democracy from below? How else could the idea of control by the workers by hand or by brain’ be expressed?

The issues of how to ensure democratic control and accountability from below have a long pedigree in UK history. Perhaps the modern idea of universal involvement is best dated back to the Putney debates of 1647. Working class opposition to the power of capital could be seen to start in the late 1820s and 1830s with an explosion of collective and radical organisation from below that both expressed opposition to profit, alternative demands and vision as well as the building of collective and democratic organisations. Examples were the Grand Consolidated Trade unions, the establishment of cooperatives and the foundation of the Chartist movement. Similar upswings in workers resistance, the creation of collective organisation together with radical economic, social, and political demands were experienced in the early 1870s, the late 1880s, in the 10 years leading up to the First World War, in the 10 years after and from 1945 – 1979.

From the 1880s the influence of socialist ideas started to have an impact on workers’ demands and the idea of more general collective solidarity. A key mobilising – and what we would call transitional demand – was for the ‘living wage’ which was counterposed in direct opposition to the ideas of the market determining wages in the period just before the First World War. Debates on the left about the importance of these movements to radical social change have had to engage with how transition actually takes place and of course where workers started to experience some democracy and ability to vote how this route relates to collective direct action has and remains central to the issue of radical transformation and working class power. It was the key issue of division between Henry Hyndman and the Social Democratic Federation and William Morris and the Socialist League. Internationally Marx and Engels, particularly after the Paris Commune, emphasised direct action and the creative development of new forms of democratic control from below as this recent article argues.

Radical politics and the transition to socialism

Perhaps the most recent and worked through discussion about taking power and the transition from capitalism has been in the collective works of István Mészáros. He argues that based upon the existence of ‘substantive equality’

‘The socialist hegemonic alternative [to capitalism’s command hierarchy] therefore involves the reconstitution of the objective dialectic of the parts and the whole in a non-adversarial way, from the smallest reproductive constitutive cells to the most comprehensive productive and distributive relations. The success of planning depends on the will coordination of their productive and distributive activities by those who have to realise the consciously envisaged aims. This genuine planning is inconceivable without substantive democratic decision making from below through which both the lateral coordination and the comprehensive integration of reproductive practices becomes feasible. And vice versa. For without the consciously planned and comprehensively coordinated exercise of the creative energies and skills, all talk about the democratic decision making of the individuals is without substance. Only the two together can define the elementary requirements of the socialist hegemonic alternative to capital’s social metabolic order.’ Beyond Capital 1995 section 20.5

For Mészáros and it is suggested here Left Unity, this analysis proposes two things. A key break and challenge to capitalism is to transform social processes internationally away from command structures to those where the needs of humanity and the planet are addressed through planning under democratic and collective control from below. Secondly, it suggests in terms of radical and prefigurative political practice, a hierarchical command structure cannot be radically transformed by another but only through political resistance and campaigns that mobilise democratic collective power from below; and constantly raise the question of a radical eco-socialist alternative in its strategic demands: thus demonstrating, as far as possible, how substantive equality and non-hierarchical democracy work in practice.

The ‘red thread of resistance’

The political praxis that is being suggested here can be seen as a ‘red thread of resistance’ running through every attempt to challenge the strategies and power of capitalism and capitalists. Whatever we campaign about, however we do it, through direct action or electoral processes, the ‘red thread of resistance’ provides a coherent and consistently radical approach. To make such a political praxis clear it is useful to draw on the socialist history of transitional demands and actions. Essentially to quote from this piece which was published in the Transform journal July 2017:

‘When developing the aims of a campaign the question needs to be asked: what demands do people care about and how can they be worded so they appeal beyond the campaign and directly challenge the power and strategies of capital? Then in terms of transitional actions the question needs to be asked: how best can we use the power and resources currently available to us to create an alternative and radical space that similarly challenges the power and strategies of capital and at the same time inspires others to do the same?’

The ‘red thread of resistance’ is therefore a political praxis that is essentially aiming to constantly form a bridge between where we are and where we need to be both in terms of demands and our actions, including a total commitment to collective democracy, accountability, and openness through developing transitional demands and actions. This is not about reforms that do not challenge capital or serve to incorporate workers into neo liberal or social democratic compromises, but constantly seek to be contentious and challenge the power and strategies of capital: ‘non-reformist reforms’. A key understanding is the idea of the ‘frontier of control’ with capital and our constantly pushing forward this frontier by taking power from them or rendering weak and inoperable. Where compromise takes place, it is due to the state of the balance of forces and is openly agreed and is not sought as a sell-out ‘exit strategy’. Sustaining collective democracy and organisation needs constant attention, so there is a future chance of coming back or continuing to resist the strategies of capital – it is a case of ‘building the future in the present’. Working through the People’s Assembly Wales we have tried to put this into practice over the last eight years. One ingredient is still needed to pull the ‘threads’ together: a political party that supports this approach and helps to ensure that the demands and actions raised in separate campaigns have a focus and unity in seeking to end capitalism.

This is the context of the Left Unity Wales democracy motion and the debate we suggested that we should have. There is existing policy on many areas which can be seen as being part of the ‘red thread’ but as we have found in Wales in the recent Senedd elections and in having to engage with the politics of independence, there is little specifically on these areas, and we have had to develop our own. Our motion was an attempt to share the outcome of that experience.

Section three of our motion was composed of a suggested list of demands, some more specific than others, which are about democratically radically challenging the UK state to such an extent that the current hierarchical power relations would be undermined. Some are more longer-term principles, others, such as those relating to councils and councillors, could be put into practice at that level if electoral control was won. They are not an exhaustive list but started to gain attention politically in Wales during the Senedd elections as no party or candidate was taking such positions.

Section two which relates to independence and self-determination of the countries of the UK seems to have attracted most criticism. Within the context of the breaking of the hierarchical power of capital outlined above, devolving as much power as possible down to democratic governance at the community, council, regional and country level would be consistent with ‘substantive democratic decision making from below’ in the Mészáros quote above. National self-determination was a key principle supported by Lenin and Trotsky and several early conferences of the Third International. More specifically, in Scotland and more lately in Wales, there has been growing support for independence and whilst this is supported for the reasons stated here, it has also immediately and directly raised the question of the need to engage and support the movements for independence whilst at the same time raise the question of ‘independence for what’ so as to be able to put a ‘red thread’ radical independence case composed of internationalist eco-socialist transitional actions and demands including collective democratic political practice constitutional changes that would radically devolve power down. It is essential to do this to challenge the trend that exists in all independence movements towards an excluding form of nationalism, or even national chauvinism.

Socialism is about the working class taking power from the rich through collective mobilisation and self-activity from below. It is about instituting collective and democratic control of the means of production for the needs of the people and planet. What those needs are must be determined collectively through democratic control of planning by all citizens with equal human rights. Socialism is about the rational application of dialectic praxis with equal citizens taking responsibility for their actions and collectively learning from mistakes. Constant democratic accountability and openness of all information of decision-making processes is an absolute to ensuring needs are met and decisions retain collective support – legitimacy – and effective application. Such a process requires everyone to be equipped with the ability to contribute their own creative thoughts and ability to decisions at all levels. It enables the release of human creativity for the benefit of all and the planet and not profit.

Such a concept is in direct opposition to the ‘we know what is good for you’ versions of ‘socialism’ exemplified by social democracy and Stalinism. As Marx says, ‘who educates the educators!’, we all become educators and learn from each other and our collective actions.

Hence the driving force of all our current demands and political practice has to be about putting dialectical praxis in operation, demonstrating how it is possible for workers ‘by hand or by brain’ to take control, understand and make decisions in all areas of understanding and at all levels of implication.

A red thread of resistance must tie all our actions together. Pushing constantly at the frontier of control through transitional demands and actions.

2. Class and Nation

In his article, David Landau addresses some of the many issues that socialists need to confront when engaging with nationalist movements. It is perfectly possible to look at each of these in turn and try to address David’s concerns individually. For instance, since when did the existence of borders prevent workers organising international solidarity with others in struggle? The Black Lives Matter and climate campaigns have hardly been confined within national borders. Trade unionism in Britain has rarely been weaker as David says, but this has nothing to do with national union structures per se. Some unions like Unite have always operated across international borders. Others like the EIS and NEU have never organised across the whole of the UK. There would be no conceivable barrier to workers in an independent Scotland joining or remaining in unions which operated across the British Isles. Current union weakness is the result of persistent attacks on workers’ living standards and employment conditions aimed at driving up the rate of exploitation. It has little to do with bureaucratic structures.

For the purposes of this debate, it is probably better to focus on, what we consider, a flaw in the basic premise of David’s argument. He concludes that socialists face a choice; either the break-up of Britain under the centrifugal forces unleashed by Brexit, or class solidarity aimed at building a ‘united socialist republic of Scotland, Wales and England’. At an abstract level we would agree. Unfortunately, as one Marxist historian of Scottish nationalism bluntly points out: ‘we are rarely granted the luxury of deciding the terrain upon which we have to fight’. Arguably nationalism is that terrain within the UK.

Nationalism: an unavoidable terrain of struggle for socialists

To understand this, we need firstly to consider the character and history of British nationalism. British nationalism has been a powerful force shaping the union state for more than 300 years. It has deep material roots in Britain’s early industrialisation, empire, and the constitutional settlement that emerged out of the “Glorious Revolution” and the 1707 Acts of Union. Such factors not only shaped a ruling class nationalist ideology based on imperialism, racism, and British exceptionalism. They also underpinned Britain’s pre-modern democracy. And they permeated deeply into working class consciousness, influencing forms of class struggle, worker organisation including the character of British trade unionism, and the politics of the Labour Party. As such, British nationalism has formed a powerful ‘glue’ holding together the constituent nations of Great Britain, incorporating differing national traditions and histories into the narratives of Britain’s ‘Empire state’. The ‘glue’ started to dissolve as Britain declined both politically and economically. A process that began before the Second World War but accelerated with the dissolution of the British Empire. And more especially as the post-1945 settlement, which had sustained British nationalism during the 1950s and 60s, was eroded following the return of economic crises in the 1970s and 80s. It is at this point that the economic impact of decline fuelled the initial political breakthrough of Scottish and, to a more limited extent Welsh, nationalisms in their modern form. Consequently, the potential break-up of the Union became a material possibility. Arguably globalisation coupled with military adventurism in the 1980s and 90s partially restored the ‘glue’. But Blair’s illegal Iraq war and the multi-faceted capitalist crises of 2008 and the pandemic, in conjunction with Brexit have shattered the remnants of cohesive British nationalism (Perry Anderson 2020).

Janus-faced nationalism

Secondly, we need a theoretical framework to help deal with the political circumstances resulting from this history. Although he moved away from his Marxist roots and closer to Scottish nationalism, Tom Nairn elaborated a theory of nationalism in the mid-1970s that still provides useful insights for socialists trying to grapple with the potential breakup of Britain today. Insights that help socialists avoid some of the pitfalls of engaging with nationalism that David discusses. Such as trying to distinguish between ‘progressive’ and ‘reactionary’ nationalisms, the idea of ‘critical support’ for nationalism or relying on the abstract notion of ‘self-determination’.

Nairn pointed out that nationalism in its modern form emerges inevitably as capitalism develops. Its concrete aspects, in different bourgeois states, are rooted in the combined and uneven development of capitalism as it grew into a world system. Identity, which David refers to, is not unimportant. But nationalism is born alongside the exploitation and oppression inherent in the capitalist mode of production. This has two immediate implications. Socialists cannot just counterpose ‘class politics’ to nationalism. Class politics is inescapably refracted through nationalism. Workers are conscious agents of change not because they yearn for the solidarity of identity, but because they are forced to act collectively in the face of the exploitation and oppression at the root of surplus value extraction. They make their own history but in circumstances ‘existing and transmitted from the past’ (Marx). Nationalism is the dominant political and cultural ‘circumstance’ produced by the uneven development of capitalism. Socialists do not get to pick or choose whether we engage with it.

Independence not Nationalism

David is of course correct to say that nationalism is ‘dangerous’. Nairn’s second important insight into nationalism was to point out the danger of trying to distinguish between ‘progressive’ nationalisms (Scottish, Welsh and Irish?) and ‘reactionary’ nationalisms (English?). He used the metaphor of the two-faced Janus, the Roman god of doorways, to argue that all nationalisms are both reactionary and progressive at the same time. To imagine the future, nationalism inevitably draws on elements of exclusiveness and national particularity from the past. Nationalism is a terrain of struggle we cannot avoid as socialists. But simply giving ‘conditional support’ to ‘progressive’ nationalism is always a dead end. In Scotland for example it has led some Lexit supporting socialists to abandon internationalism in favour of left economic nationalism. For example, advocating ‘Scandinavian model’ welfare capitalism, or high value ‘niche production’ within global supply chains.

Independence in Wales, Scotland or England will not of course end capitalism but there is no reason for socialists to compromise our politics. The break-up of Britain alone would be a massive blow to imperialism worldwide (Fotheringham 2021, p402). But it is possible to go further and help forge a radical vision of independence which would shift the ‘frontier of control’ in favour of working-class people (Arthur 2017). Doing so, as argued earlier, requires a programme of transitional demands and actions encompassing eco-socialist ideas, and a massive extension and deepening of democratic control over our social and economic lives.

Revisiting republican socialism

An essential aspect of this is to challenge the democratic deficiencies embodied in the UK’s archaic constitutional structures. It is here that some of the insights of republican socialism are essential. Arguing for a social republican form of government within the constituent nations of the UK, based on popular sovereignty and grass roots democracy is therefore a vital transitional demand for three reasons. Firstly, if we believe that the emancipation of the working class can only be carried out by the class itself, then any transitional programme must elaborate demands and actions that can advance workers’ democratic control over all aspects of their economic and social lives – state, community, workplace. Secondly, any gains workers make in the struggle around eco-socialist demands will only be temporary if we leave the political structures of the British state unchallenged. This has surely been the lesson of the whole post-war period. The roll back of the welfare state, privatisation, attacks on trade union rights, illegal wars obviously reflect the balance of class forces. But they have all been facilitated by an archaic constitutional structure based on notions of parliamentary sovereignty, a pre-modern electoral system and ‘crown powers’ that deny popular sovereignty and limit democratic scrutiny of decision taking at all levels of society. Thirdly, having clear perspectives on democracy and constitutional questions also avoids the trap of federalism into which David seems to fall at the end of his piece. Federalism and enhanced devolution have been much debated over the years in the context of Scottish independence. (see here, and here). The problem is not federalism itself but who gets to decide the constitutional form and limits of a federal UK. The current balance of class forces makes a frontal assault on the British State to achieve David’s ‘Socialist republic’ of Britain unlikely to say the least. Independence based on a grass roots republican constitution and popular sovereignty with the deepest and most extensive democracy we can achieve, would at least give workers in the constituent nations of the UK the freedom to choose federalism and shape its form and content, rather than have it imposed by an unreconstructed Westminster.

Towards a conclusion

We have tried to outline the theory and practice behind Wales Left Unity’s engagement with the national question. The motion we brought to National Council recently was intended to reflect our experience and suggest how socialists might approach the question of nationalism and the break-up of Britain. We have deliberately avoided addressing the ‘English question’ directly. This is something that later contributions to this debate must take up. It will become increasingly important for socialists to do so over the coming period. There is nothing incompatible between fighting for a radical eco-socialist and democratic independent Wales, Scotland, and England, and building grass roots working class solidarity across these islands and beyond.

Additional References:

Anderson Perry: Ukania Perpetua? New Left Review, Sept/Oct 2020

Arthur L: Where we are and where we could be: transitional demands and actions, Transform Journal 2/2017

Davidson N, Discovering the Scottish revolution 1692-1746, 2003, Pluto Press, London

Fotheringham B, Sherry D, and Bryce C (eds), Breaking up the British State, 2021, Bookmarks, London

Jackson B, The case for Scottish Independence, 2020, Cambridge University Press.

Marx K: The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: Marx/Engels Archive

Nairn T: The Break-Up of Britain, 3rd Edition, 2021 Verso, London

1 comment

One response to “Socialism, Democracy, and the Break-up of Britain”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

Wednesday 17th September: Trump not Welcome

National Demonstration against Trump’s state visit

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Thoughts on Socialism, Democracy and the Break-up of Britain

Socialism from Below A really positive aspect of the document from Len and Craig is the emphasis on socialism from below and the creation of new instruments and forms of democratic control created by the people themselves. It follows that there is a necessary and intimate connection between socialism and democracy.

We need to remind ourselves of this when we make demands on the capitalist state, as we often must, or when we stand in elections or become councillors or whatever. We might engage with the existing state in these ways but ultimately we must dismantle them and build new things from the grass roots up. So I think we are singing from the same song sheet here.

I am dubious about calling this Republican Socialism. I would call it Revolutionary Democratic Socialism or some such.

Democracy and Nationalism I lose the thread that leads from this higher all pervasive understanding democracy to nationalism or to independence. I would have thought that this revitalised democracy is a central pillar to an alternative to nationalism. I would have thought that it is having real power, having the ability to transform the world which many nationalists in Scotland may really be seeking and organisations like the SNP try and hold out that promise. But of course I am not on the ground. As Marx (18th Brumaire)said “And just as they seem engaged in revolutionising themselves and things, in creating something has never yet existed……they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their services and borrow from them names, battle cries and costumes in order to present the new scene world history”. Clearly this means that the engagement with these nationalists is hugely important but not as the left half of the Janus face.

I would add that there ARE threads running between democracy and alternatives to nationalism.

• The Jewish Bund. This was a much stronger movement than Zionism in the 1930s and was opposed to it. Marching under the banner of “We are Here”, they developed lots of Jewish radical institutions that engaged people in new ways, local councils. Socialist schools and the rest of it. They were, as we know, destroyed by the Nazis.

• The ‘Romanistan Movement’ developing amongst Roma, Gypsies and Travellers. They aim to be a ‘nation without a territory or borders’. The idea is to develop local and regional democratic structures in pretty well all countries and to develop a network through the internet so as to have a global presence, have elections, referenda etc. Still refer to a nationalist framework (quite fiercely ‘we are a Nation not an Ethnic Minority’)

National Self-Determination Despite being championed by the likes of Lenin and Trotsky I find the concept of national self-determination difficult to unpack and apply and in some cases downright unhelpful. Take the case of the partition of India in 1947, one of the bloodiest episodes of the 20th Century (I don’t have a deep knowledge). How does the concept of national self-determination help us navigate our way through this? The first step seems straight forward. People call for the END OF BRITISH RULE. But over centuries of British rule, imperialism had cultivated conflicting nationalisms –opposing poles of belonging. The Empire’s final stroke as it left was to impose partition. So we had two opposed nationalist movements; one (mainly Muslim) wanting an independence from India so supporting partition and the establishment of Pakistan and the other opposing partition. Both movements seized the principle of national self-determinism to justify their position. (It’s even more complicated because some Sikhs wanted their own state in the Punjab, again calling on the principle of national self-determination whilst others wanted to be part of a united India).

Fundamentally it seems to me that if you replace one country with two (or more) the question arises what happens to the minority living in the ‘other’ country. It seems to me that some kind of aparthied or, worse, ethnic cleansing is likely. I am not suggesting that the partition between England and Scotland would be remotely like India and Pakistan in 1947! I can imagine an English movement saying to Scottish and Welsh people “Go off to your own country”.

England’s Coming Home The events of the last couple of weeks with the England team taking the knee, the government’s support for the booing, the missed penalties, the abuse, Gareth Southgate’s letter and the grass roots response to that abuse.

Southgate’s letter is interesting. It paints a picture of Englishness, or what Englishness should be, as a multi-cultural multi racial thing to which ALL can belong. It is not Republican. It is not Socialist. But it is a challenge to the exclusionary nature of nationalism. It is tempting to see it in the terms of Tom Nairn, Len and Craig as the Janus face of nationalism facing both ways – Southgate and Rushford are the left face while Patel and Johnson are the right face. But I am not so sure. Southgate certainly seeks a progressive Englishness. This, I am sure is genuine but England was the focus, because, obviously, it was about the English football team. The vast majority of thousands of people who came out supporting Southgate and the team, especially at the Mark Rushford Mural, were anti-racist but not necessarily that concerned about Englishness as such. Good! Anyway, I think we won that match against the bigots and the government.

If Team GB were to take the knee in Tokyo and the same row takes place would it have gone the same way, only this time the focus being on Britain not England?

So I remain unconvinced that there is a sharp distinction between English nationalism and British nationalism, amongst the English that is.

Len and Craig are surely right to say that British Nationalism is the glue that held the empire together and now holds the UK together. But I still don’t think the little Englander and the Great Britisher are very different and are often they same people. Their shared values are rooted in imperialist history and become distinct at all when the Acts of Union, when England becomes the dominant part of Britain rather than Britain itself.

When people rallied to defend the English team from the Government and racist bigots I don’t think this was a progressive nationalism but probably largely anti-nationalist and anti-racist. The true face of nationalism is firmly reactionary.

David Landau