Reform, Revolution, Education and Agitation

In a discussion about the merits of the Platforms that have been submitted within Left Unity, I was asked why I call the Left Party Platform ‘left reformist’ as opposed to ‘a different kind of socialist?’, says Ian Donovan from Southwark Left Unity.

I think the differences between these platforms are more important than simply a nuance within a common set of ideas. I think they are different sets of ideas. Take a look at the clearest statement of overall purpose in the Left Party Platform itself:

“As yet we have no viable political alternative to the left of Labour, yet we urgently need a new political party which rejects austerity and war, which will defend and restore the gains of the past, fighting to take back into public ownership those industries and utilities privatised over the last three decades, but will also move forward with a vision of a transformed society: a party which advocates and fights for the democratisation of our society, economy, state and political institutions, transforming these arenas in the interests of the majority.”

This, both by what it does not say and by what it clearly does say, points to a perspective of merely different policies to be achieved within existing institutions. It seeks to ‘transform’ existing institutions, not destroy and replace them with something fundamentally different. That is, it is primarily about electing a different government with different policies, hostile to neo-liberalism as a policy and indeed aiming to reverse neo-liberalism’s attacks on the previous (in this country, pre-Thatcher) social-democratic settlement, but within the same overall political, and (implicitly) economic system as we are under now. This becomes clearer when you look at which parties it calls for alliances with uncritically:

“In Greece, France, Germany and elsewhere, new political parties have developed, drawing together a range of left forces, posing political, social and economic alternatives. They are anti-capitalist parties that stand against neo-liberalism and the destruction of welfare states – whether at the hands of the right or of social democracy – and fight for alternative social, economic and political policies.”

This is talking about parties like Syriza in Greece, De Linke in Germany, the Front De Gauche in France. All of whom have the perspective that the old Social Democratic parties have betrayed their previous, reformist, socialist policies, and need to be replaced by something that stands for what those parties ‘used to’ stand for. That is, reformist ‘socialism’; socialism through the existing institutions.

Obviously, we will have to have a relationship with these parties. But what kind of relationship? Should we not be seeking to ally with and encourage elements who want to go further in their socialist aspirations and look for ways to destroy capitalism itself, and not be content with just the highly problematic perspective of electing a government that will supposedly ‘transform’ existing institutions from above?

Nowhere in the Left Party Platform is there any mention of the need to destroy the existing state machine. This could perhaps be more clearly spelled out in the Socialist Platform, but the perspective is there. That is the ‘abstraction’ and the ‘divisive’ idea that some comrades are criticising.

I will emphasise again: the real reason why Labour and the other social-democratic parties have abandoned social reform in favour of neo-liberalism is not a mere change of ideas in the abstract. Rather, it is because to those charged with implementing it, the reformist project has become unviable as capitalism’s crisis of profitability has deepened. Without a frontal attack on the rights of private property and on the capitalist state(s) on an international scale, social reforms cannot today be wrested from the capitalists.

It would take a serious threat of revolution to extract any serious gains even in the short term, and we could then expect a determined attempt to crush those movements that achieved them by whatever means are to hand and to roll back any such gains, in a similarly short term. The only way to fully achieve and consolidate real social gains is to destroy the existing state of capital and forcibly take away their property. This is not a period any major economic expansion and social reform under capitalism is possible, as seemed to be true in the post-WWII boom.

That was not the ‘normal’ state of capitalism, a capitalism of full employment and welfare, but rather an exceptional boom created (ironically, but fully in keeping with capitalism’s brutal logic) by some of the worst defeats of the working class in history (in the 1930s, under Hitler and Stalin), together with the rise to world capitalist hegemony of the United States. The normal state of capitalism is slump, depression and the threat of war and barbarism – the latter two were also always present during the post-WWII boom.

The implications of these issues were spelled out by Rosa Luxemburg in her famous pamphlet Reform or Revolution, written in the context of similar debates within Germany Social Democracy where ‘reform or revolution’ was being seriously contested:

“Every legal constitution is the product of a revolution. In the history of classes, revolution is the act of political creation, while legislation is the political expression of the life of a society that has already come into being. Work for reform does not contain its own force independent from revolution. During every historic period, work for reforms is carried on only in the direction given to it by the impetus of the last revolution and continues as long as the impulsion from the last revolution continues to make itself felt. Or, to put it more concretely, in each historic period work for reforms is carried on only in the framework of the social form created by the last revolution. Here is the kernel of the problem.”

“It is contrary to history to represent work for reforms as a long-drawn out revolution and revolution as a condensed series of reforms. A social transformation and a legislative reform do not differ according to their duration but according to their content. The secret of historic change through the utilisation of political power resides precisely in the transformation of simple quantitative modification into a new quality, or to speak more concretely, in the passage of an historic period from one given form of society to another.”

“That is why people who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place and in contradistinction to the conquest of political power and social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal. Instead of taking a stand for the establishment of a new society they take a stand for surface modifications of the old society. If we follow the political conceptions of revisionism, we arrive at the same conclusion that is reached when we follow the economic theories of revisionism. Our program becomes not the realisation of socialism, but the reform of capitalism; not the suppression of the wage labour system but the diminution of exploitation, that is, the suppression of the abuses of capitalism instead of suppression of capitalism itself.”

This was written in a period, prior to the First World War, when social reform seemed to many to be seriously on the agenda and the reformists were achieving a dominant position in Social Democracy.

Today, few in the working class believe such a perspective is realistic. The trade union and labour bureaucracy does not believe it and does not practice it – it at best fails to lead resistance, at worst overtly collaborates in capitalist attacks and hence working class support for it is in a steep, strategic decline. Reformism has always been the ideology of the bureaucracy, which is a distinct social layer that exists to act as negotiators over wages and conditions between workers and capitalists, but which would be redundant if the capital-labour relationship were to be abolished. Hence when push comes to shove, the mainstream bureaucracy believes and practices the view that the working class must sacrifice many of its previously won gains to save the system.

It is undoubtedly true that considerably fewer believe in the possibility of revolutionary change today than believe that reformism is a viable strategy. Many of our potential recruits have no particular coherent strategy in mind to take things forward, just the gut understand that things are getting worse and worse and something needs to be done to resist this politically. The question is what does reformism have to offer them, as opposed to revolutionary socialism?

As I see it the only way to win real gains from capitalism today is by mass struggle. That means large scale strikes, and mass strike movements, have to be seen and fought for as the weapon of resistance to break the will of the capitalists.

But we are not in a position to lead strikes on any significant scale at the moment. What should socialists do about this?

Accept that we are in no position to do this, and buckle down to election campaigns so that we can end up, as some have explicitly argued in this discussion already, making alliances on local councils with other parties that support capitalism in one form or another, and thereby inevitably being dragged down to their level and made complicit in their crimes? Such a perspective does not inspire me, and I doubt it will inspire many others either.

The other possibility, given we are not in a position right now to lead mass struggles, is to start a propaganda and education campaign aimed at educating both ourselves, and layers of the working class who are looking for some way to counter the current reactionary offensive, on the importance of revolutionary methods, on how to propagate the need for actions up to, including and beyond a general strike, in order to win some victories after decades of defeats of our side.

By propaganda and education I do not mean like a schoolroom – though formal debates, forums and the like have their place. I mean finding ways to promote discussion among wider layers, among people involved in campaigns over everything from hospital closures to industrial disputes to struggles against government-sponsored xenophobia and racism, or many other things.

Our election campaigns should not be about getting elected to serve as lobby fodder on powerless local authorities, but as platforms for education and agitation in the spirit of mass action and the need for working class revolt.

If we are to do election campaigns, we need to re-establish a tradition of electoral work that is not reformist, and that is not bound up with petty electoral manoeuvres at local level. We should try to emulate the kind of revolutionary electoral work done by the early Communist movement, by the Russian Bolsheviks in the Tsarist Duma prior during the First World War, and in general the kind of electoral work that was done by socialists before the workers movement was crippled by reformism and the degeneration of the official Communist movement. It would be good to study some of these things, critically, and try to distil some applicable lessons for today from them.

Even if we can only make modest beginnings in this regard, in the long term it will pay dividends, and will have the benefit of this project avoiding discrediting itself by getting involved in electoral opportunism, which has brought discredit on previous attempts to fill the gap to the left of Labour, with warmed over left-reformism or even left populism. The crisis of Labour, and other similar parties around the world, is a crisis of reformism in general, not just of particular organisations. The solution to it is not an attempt to put Humpty-Dumpty back together again, but to build an alternative that really does seek a social revolution, to put the working class in power and do away with capitalism completely.

6 comments

6 responses to “Reform, Revolution, Education and Agitation”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

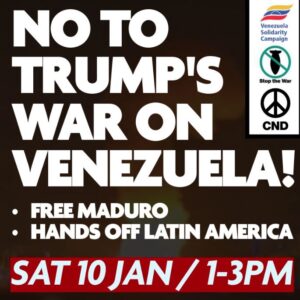

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Ian, this is one of the most interesting contributions I have read on the Left Unity website and I think your conclusion is spot on. I have something to add which I think supports it more recently.

When I was working in Oldham during the previous decade, in the post-riot context of 16,000 BNP voters, a small group of us decided the only way to stop the continued growth of the BNP was to confront their ideology and what they were saying inside the largely working class wards which had become their stronghold. We did this by copying them – in their strongest wards we started to produce and distribute local newsletters, not overtly or even mainly anti-racist, but instead taking up local issues and carrying interviews with local people who had the interests of the local community very much at heart. In each newsletter there was a local example that showed that racism was making it less, not more likely, for the community to get its issues resolved but this was kept in the background, not splashed on the front page. It took two years of this quiet but consistent grassroots work, which was not centred on election times, although we produced newsletters then as well. We did not talk about criminal records and we did not moralise; we talked about real local political issues and what could be done about them.

Over two years we quartered the BNP vote in their four core wards. Both the Council and the Manchester Lollypop parachutists loudly claimed responsibility for what we managed, but their work just reproduced what had failed so many times before.

This is why I agree with your proposed perspective on electoral work.

I really don’t understand this desire from some within Left Unity to create a revolutionary party that wants so “smash” capitalism. Using these sort of terms is simply going to scare away the majority who don’t know enough about the system to even consider supporting a move ‘to smash it’.

There are plenty of unsuccessful far-left parties/organisations in the UK who call for similar things that supporters of such rhetoric can go and support. Its utterly pointless to add another one to that mix.

I think it completely misunderstands the point of the whole Left Unity concept, to create a broad left party which can harness austerity discontent across Britain.

The fact of the matter is, its the broad left parties that are successful. The ones mentioned above – Front de Gauche, Syriza. Even in the UK, perhaps the most successful left-wing party of recent times, RESPECT, was a broad left party that stayed away from demands to smash capitalism and revolt. Even left-wing governments like those in Venezuela and Ecuador may be anti-oligarchical/neo-liberal/capitalist but there are reasons they tentatively remain within the system.

Supporting the Left Party Platform isn’t watering down our politics in an attempt to gain votes, its about recognising todays politics and society and offering something that suits the millions of UK people who are struggling against austerity. Something these people can recognise and get involved in.

Sam, let’s treat these two issues separately, please.

As for language, I agree that we need to be careful about our vocabulary. ‘Smash’ is a word with connotations of a violence that most people almost instinctively would abhor. There is another article on this website which tries to dismantle and suggest alternatives to traditional left-wing jargon and I am all for this. All jargon is alienating to the vast majority of people and needs to be avoided.

But if you look beyond the vocabulary to what Ian is saying, the broad left parties you list are limited in precisely the way he outlines – their success is all about their sudden emergence, their ability, as you say, to reflect and provide a vehicle for anger about neo liberal austerity policies, but it is what they do and don’t do after this initial success that matters – they burn out because of the want of an alternative. If you really think that you can use existing institutions to effect the kind of radical changes which would reverse the past 30 years, I think you need to prove the case, otherwise you are leading people ‘up the garden path’.

This is Britain we are talking about, not Latin America or southern Europe – a nuclear power joined at the hip to the USA and the NATO alliance, with an undemocratic political structure, a floridly right wing press and a place where the dominant belief system was laid down by Margaret Thatcher. We have to start to find a way to win the battle of ideas against this consensus over a decade or longer or the Left will remain what it has been since the 1970s – a chameleon which sheds its skin regularly but has no tangible impact on politics or on the ability of working people to move beyond single issue militancy.

That is the danger of the Left Platform in its current form.

I agree with John that electoral work which only happens during elections is worse than useless, there has to be long-term work in communities including campaigning – and there’s plenty to be campaigning on including anti-racism, anti-austerity, anti-cuts, etc. – and this should be combined with standing in elections at local and national level. Of course the record in local government of some broad left groups in Britain such as Respect is not very positive and LU should not at present aim to win whole councils, etc. for without mass support a sell-out is almost inevitable.

However Ian’s article is really about pushing LU into adopting a revolutionary programme and as Sam points out there are already several revolutionary groups (hardly parties) in Britain that Ian and others who are promoting this idea could join. But it’s also the case that their influence over the last decades has not been very great. Even the SWP’s building of the Stop the War Coalition, despite the huge demos they organised which were real achievements, did not build the SWP itself. So for LU to adopt a revolutionary programme would cut it off from the mass of people who are opposed to the politics of the Coalition and the almost invisible opposition of the Labour Party, but are not convinced of the need ‘to destroy the existing state machine’.

It is possible for revolutionaries to be part of LU but to demand that LU in its early days adopt such a set of ideas would mean less rather than more influence on events.

Just as an aside I think a Syriza-type party would be a good thing in Britain rather than a barrier to the building of socialism. And it’s significant that at their recent conference 30% of votes went to the left platform. There is obviously a battle going on between those who support ‘socialism through the existing institutions’ and those in the left platform who have more radical solutions, such as leaving the Euro. But Greece has a deep political crisis in which the class struggle is at a completely different level to Britain. The situation in Syriza shows how a broad party can develop – both positively and negatively – in the face of the collapse of society. But it’s most unlikely that it could have grown so big and so fast if they had adopted a ‘smash the state’ positon at its inception.

“However Ian’s article is really about pushing LU into adopting a revolutionary programme and as Sam points out there are already several revolutionary groups (hardly parties) in Britain that Ian and others who are promoting this idea could join. But it’s also the case that their influence over the last decades has not been very great. Even the SWP’s building of the Stop the War Coalition, despite the huge demos they organised which were real achievements, did not build the SWP itself. So for LU to adopt a revolutionary programme would cut it off from the mass of people who are opposed to the politics of the Coalition and the almost invisible opposition of the Labour Party, but are not convinced of the need ‘to destroy the existing state machine’.”

I just think this is something I should come back on, because as a criticism it shows such misunderstanding of the problems of the left today. Jane says that those who want to openly fight to win the ‘broad’ project to revolutionary views should go and join one of the ‘revolutionary groups’. But which ‘revolutionary’ group is she talking about?

The largest such ‘revolutionary groups’ so-called are the SWP and the Socialist Party. The first spent rather a long time in the last few years making sure that the various broad projects it was involved in embraced reformist politics, putting their members under discipline to vote down political positions that were to the left of reformism first in the Socialist Alliance, then in Respect. It was only the political stance of the maverick ex-Labour MP George Galloway that gave Respect a genuinely radical edge over Iraq and the Middle East; they tailed after his gut level anti-imperialism abroad while on domestic issues made sure Respect was ‘old Labour’ to the marrow of its bones. The Socialist Party got into a bitter tactical row with the SWP over organisational questions, and left the Socialist Alliance because of that, but agreed on the necessity to keep things “old Labour”. Look at TUSC.

Other supposedly revolutionary groups generally either helped the larger ones do that, abstained completely, or in the case of the CPGB, advocated eclectic and incoherent positions that undercut the positive role it might have played. I don’t see anything of that type remotely worth joining; bringing genuine socialism to the ‘broad’ project is the correct thing to do, it seems to me.

The place for revolutionary ideas is in the broad movement, not some sect that advocates them in a platonic way while voting against them where it counts. If the ‘broad’ movement cannot deal with openly socialist and revolutionary ideas being advocated within it, how broad is it really? Is it not thereby following the political locomotive (driven by the most conscious sections of the ruling class) that is pulling the entire political spectrum to the right?

Don’t you think that the proper role of such a broad project is to assemble a dynamic and coherent political formation that can begin to seriously pull politics in the opposite direction? And if that is what we are aiming for – and I’m sure for most if not all of us it is, is it not the case that revolutionary positions ought to play the major role in that?

I am pretty self-critical that I and others were in the past too deferential to opportunist and reformist forces, in the SLP, in the Socialist Alliance, and Respect, that were determined to keep these formations safe for failed old Labour politics. If this project is also to be kept ‘safe’ for that, it will end up with the same problems, as it was not the personal foibles of the various reformist personalities who were involved in that that led them to disaster, but social-democratic politics, that necessarily generate social-democratic bureaucratism, even on a small scale.

ian writes well, good to hear from jane and socialist resistance.

the difference in a nutshell is whether people in left unity believe that capitalism can be reformed by a radical party or whether capitalism can only be smashed by working class conscious action.

i dont agree that the unions can play no part. we have to fight with others to transform the unions to make the unions fight!

JAne retains the position of being a revolutionary, but a sensible one, who waits for the right time before arguing for her politics to be adopted. but it is really forming a leadership block with the right against the left. this is unprincipled, in my view.

a number of contributors suggest other places that socialists could go to, those that proclaim their socialist positions that is. but wasnt the original founding statements about forming a socialist party.

are we shifting to the right so soon?

the debate on platform is vital to establish the aims and objectives, without which their will be the tendancy to slide into a non specific radicalism.

jane seems to prefer this, which is strange for a socialist and socialist group. i would urge jane turns to the left. we should at least register where we stand. a vote for socialist platform is a vote yes in the “referendum”, yes : im a socialist. This does not harm the idea of a broader party but it would register where the majority of left unity are actually coming from.

pete b