Parliament – what should we do with it?

This is part two of Sophie Katz’s article on political representation. Part one was published last week and is on the debate pages of this site.

Setting up literary utopias has been a dangerous business since Marx and Engels wrote ‘Socialism – Utopian or Scientific’ and it became catastrophic after Proudhon’s magnum opus on the ‘Philosophy of Poverty’ was reduced to ashes by Marx’s pithy rejoinder – ‘The Poverty of Philosophy.’ (He had a way with words, that man!)

In Bulgaria a utopian movement has just overthrown the government. It started with huge demonstrations against the rise in energy prices. By this February both poverty and corruption became part of the targets of the protest. PM Borisov resigned that month. New elections have been called by President Plevneliev. The streets meanwhile demand a moratorium on all power bills; no prosecutions for non-payment and councils of ordinary citizens to oversee Parliament, the National Bank; the legal system and other key state institutions. They believe (rightly) that their state in general and their Parliament in particular is rotten through and through. What is proposed, now, by the mass of young Bulgarians, is dual power. There are very historically familiar weaknesses – perhaps stimulated by recent memories of Communist Party rule. Angelo Slavchev, a 31 year old leader of the movement wants no political parties and favours a government ‘of experts.’ He (and others) describe their revolution as taking place ‘independently of politics.’ But re-nationalisation of all energy is shouted from the rooftops, as is an end to poverty living standards. (Bulgarian wages, if you are lucky enough to work, are about half the EU average at £356 per month.) In Bulgaria the mass of young people have noticed that Parliament represents a corrupt political class and, as in Spain, they denounce their MPs and ministers in the same breath as they attack the energy moguls and the billionaires.

The question of the character of their Parliament, as with los indignatos in Spain, is a central feature of the popular upsurge that Bulgarians are experiencing. Given the collapse in the strategic political purposes of Parliament in the West and the rise of a self-serving and privileged political class, it is almost certain that popular movements of any scale and depth in western countries will confront the same issue. A caveat needs entering here. In Spain, in Bulgaria and Greece, Parliaments are relatively new phenomena. In the UK by contrast Parliament is an ancient institution. In between the UK and Bulgaria is a range of representative bodies of different historical strength. The UK Parliament ‘delivered’ victory in WW2 and a welfare state. These are still active references in popular consciousness. Nevertheless, the self destruction of the independent politics of the Labour Party, not to mention expenses etc., are significant shifts towards the Bulgarian end of the spectrum. And the question is as alive in the UK as it is across the whole of the West (albeit in different ways) especially among the working classes, ‘What use is Parliament?’

At risk of being taken as a utopian, with a dreamt-up schema – let’s try to answer that question. But first the question needs to be reformulated. We should perhaps ask; – what are the barriers that need to be broken through to allow a Parliament to get to work on behalf of the people? As things stand, Parliament does not represent the vast majority of people and second it has declared a permanent moratorium on confronting, managing, even talking about, who has wealth and power.

Taking the UK again as a starting point and looking first at representation; the overwhelming majority of even the UK population, even among those who vote for them, do not believe any of the traditional mainstream parties really represent them, their lives or their experiences. There have been, as a result, the emergences of new parties (e.g. the SNP in Scotland or UKIP) that have captured a deep feeling among sectors of the population. These two are in all other senses quite different phenomena. At its most simple, people in Scotland support the SNP to give life to an anti-Tory mood and political outlook – that is unavailable if they vote Labour which is tied to the union. People in the south of England vote UKIP to give voice to an abandoned version of the old Tory Party, now also no longer available. The UKIP vote has no positive political project. It is supported by a superficial and floating political mood. The SNP on the other hand does have a political project for the Parliament (in Scotland.) And that is to deal with representation and with wealth and power by becoming a separate nation. By itself, and simply separating Westminster from the Parliament at Holyrood the SNP’s ambition truly is a utopian dream.

Everything starts from representation. Why have UKIP and the SNP been initially successful and the working class movement, since the decay of Labour, so unsuccessful in creating a new party that would represent them? That question is itself worth a book, several books. For our purposes the heart of the matter lies in the decomposition, politically, socially and culturally of the traditional working class itself. Without a working class, the capitalist system itself does not work. But for centuries socialists and others have understood the difference between a class of itself and a class for itself. As a subaltern (and now the majority of the world’s population lives in cities) the, subaltern class, the working class does not, like previous new ruling classes, build up its economic and new social structure within the prevailing mode of production, in such a way that a dual power with the old economy and the old social structure emerges gradually, and then the political conquest starts from these already established heights. On the contrary, although the working class can create its own islands of democracy and to some degree its separated-off conditions of life, it does not produce its own economy and society in the womb of capitalism. It creates its own independent organisations and its class-consciousness that is the processed experience of its battles. Political power is the precondition for its new economy and its new society.

In this context, the new reality of a working class movement only beginning to recompose itself, how should we argue the case for political representation? By quotas; by positive action. In 1900 the Labour Representation Committee, the forerunner of the Labour Party, argued for ‘working men’s representation.’ It was obvious then that it could be achieved by standing someone from the trade union movement. Today that avenue for class representation is too narrow. The minority unions (vital though they are) no longer cover a large part of the newly emerging working class. Today we require a Parliament that has at least 75% of its MPs that earn the average wage (for men £28k, for women £22k) or less. 50% of MPs need to be women and the largest ethnic minority groups need to have their quota representing their presence in the population or more in the case of some key cities. This would require new forms of election and new rules. Like the most progressive unions and their executive committees, people should have an agreed time limit in office (one or two Parliaments?) and then return to their jobs. Anybody wishing to stand would need to be part of a list (not necessarily a party list) that reflected the quotas needed. Wages of MPs would be fixed to the average wages in the country and each MP would have a paid team of three to help them. Spending on elections would be low and fixed. No media coverage of the election would be allowed in the last week of the election campaign. (This would encourage people with local roots to stand.)

In this context, the new reality of a working class movement only beginning to recompose itself, how should we argue the case for political representation? By quotas; by positive action. In 1900 the Labour Representation Committee, the forerunner of the Labour Party, argued for ‘working men’s representation.’ It was obvious then that it could be achieved by standing someone from the trade union movement. Today that avenue for class representation is too narrow. The minority unions (vital though they are) no longer cover a large part of the newly emerging working class. Today we require a Parliament that has at least 75% of its MPs that earn the average wage (for men £28k, for women £22k) or less. 50% of MPs need to be women and the largest ethnic minority groups need to have their quota representing their presence in the population or more in the case of some key cities. This would require new forms of election and new rules. Like the most progressive unions and their executive committees, people should have an agreed time limit in office (one or two Parliaments?) and then return to their jobs. Anybody wishing to stand would need to be part of a list (not necessarily a party list) that reflected the quotas needed. Wages of MPs would be fixed to the average wages in the country and each MP would have a paid team of three to help them. Spending on elections would be low and fixed. No media coverage of the election would be allowed in the last week of the election campaign. (This would encourage people with local roots to stand.)

We could speculate on the problems and the frills of such a system but the essence of the matter is clear. We have to return to a way of ensuring the representation of the new working classes in Parliament for it to be of any value whatsoever to the majority of the population.

And the significance of Parliament? Its role in modern early 21st century politics? To assert popular control over wealth and power. From the point of view of the interests of the majority, this is the burning historical issue of issues. Some vital strategic questions in the past were decided by Parliament. For example who had the right to the franchise? Who had the right to free health care, education, welfare and pensions? These gains resulted from momentous struggles. No doubt the same will happen over and direct challenge to wealth and power holders. What is for sure is that a Parliament that shies away from this question is increasingly irrelevant. And it is differences on the control of wealth and power that should define any genuine, new political currents, organisations and parties that stand in elections. If Parliament decided anything significant about who should control wealth and power, instead of its current across-the-board agreement that the status quo is either good or cannot be challenged, then western politics would cease to be the carnival of personal interest and corruption that it has become.

4 comments

4 responses to “Parliament – what should we do with it?”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

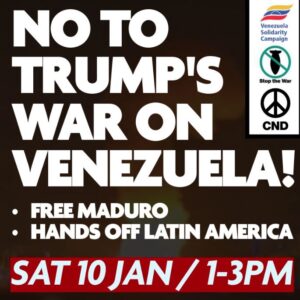

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Why do many utopian views appear to others as dystopias? Perhaps because people do not fit into theoretical or mathematical models very well. So talk of mathematical quotas horrifies many people. You say Marx had a way with words. He certainly did and so much so that most self-professed Marxists have never even read his most famous work, in German or in translation. Marx’ analysis of capitalism is, of course, very impressive, and, perhaps a clue to the problems affecting society and the political system today will be found in the title of his most famous work. Who controls the capital generated by society? Introduce a system for preventing individuals accumulating personal fortunes and some form of solution may begin to present itself. In the meantime, perhaps we should consider more what Proudhon thought capital was. Theft.

In fact situation in Bulgaria is almost a genocide one. And the wages of the majority are far below 100 pounds per month. Of course, if they are lucky enough to have a job. Things have gone out of control entirely. Add to this the ethnic problems – there is a discrimination towards Bulgarianz in favour of gypsies, who, protected by Soros and his and other Western organisations, rob, murder, beat and nobody can punish them for this. In general people want the return of socialism with the guaranteed income (lack of unemployment), the free healthcare (including dental), the free education (including university one), the lack of crime, the safety….However, confusion is really overwhelming, and the young protesters think that so-called direct democracy will do the job, but I personally don’t believe this.

Thanks you for your comments.

The point about Capital is that its system can only be overcome by politics and not by economics. So, we start from what we have. And we explain how the majority of the planet – even in the west – are excluded from politics. Then we state how the majority could have its voice heard in politics. Why? because simply making the point illustrates how far we are from where we (all) need to be.

I know little about Bulgaria. I can imagine that all sorts of Clans and Warlords grab hold of parts of a society that is crashing. I believe that mass action and the demands of the people (that have so far been reported in the west) are right and are the best defense against the rich and the people who would like to be the new rulers of Bulgaria – where ever they come from.

Separation is it Sophie ? – well to us up here, it’s called independence.

Funny reading through nearly all the posts on this website, what people are crying out for is what the SNP are trying their level best to provide for the people of Scotland, yet not one mention of the SNP as a party to look towards for policy guidance.

Protected NHS – non privatisation, end of PFI funding scandal

Free Education – no tuition fees

Free buss passes, elderly care, prescriptions and many more.

Publicly owned national water utility

Goodbye Trident, and any plans for renewal…

these are all things i”ve heard talk of here and yet not one mention of the only political party in government in the UK who is actually doing something about many of these issues. Why ?