Lineages of Ukraine’s Civic Revolt

Recently in Ukraine for an academic conference, Luke Cooper had the opportunity for a discussion with some of the participants in the ‘EuroMaidan’ movement, and to visit the encampment in Independence Square. In an attempt to understand the historical and social origins of the country’s mass protests, the following are some of his observations.

Recently in Ukraine for an academic conference, Luke Cooper had the opportunity for a discussion with some of the participants in the ‘EuroMaidan’ movement, and to visit the encampment in Independence Square. In an attempt to understand the historical and social origins of the country’s mass protests, the following are some of his observations.

Cultural legacies of state socialism

In his path-breaking essay, “Culture is Ordinary” (1958), Raymond Williams railed against that type of left wing thinking that insists upon others that they “write, think, [and] learn in certain prescribed ways”. “A culture is common meanings, the product of a whole people and offered individual meanings, the product of a committed personal and social experience”, he insisted. As such, it was “stupid and arrogant to suppose that any of these meanings can be… prescribed”, for they are “made by living, made and remade”. Williams’ critique speaks to many contemporary problems of modern politics: the privileging of a certain language and set of symbols can lead all too easily lead to a failure to understand social movements that do not fit with our preferred narratives.

Events in Kyiv over recent weeks present such a challenge. When participants tore down a statue of Lenin, it seems clear that they had a radically different interpretation of the icon’s meaning to that of the late Nelson Mandela, who famously “kept portraits of Lenin and Stalin above his desk at home”, and claimed in his autobiography to have “acquired the complete works of Marx and Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao Tse-tung and others”.

The same icon Mandela associated with his freedom struggle meant the exact opposite to the protestors in Independence Square. To get a sense of how the latter understood its meaning, consider how only last year the Russian president Vladimir Putin spoke out against the closing of the Lenin Mausoleum, and compared the late revolutionary to Christian saints (to justify the preservation of the remains rather than the burial Lenin had wanted).

Both interpretations are logical and meaningful, and each underlines the extent to which world politics continues to be shaped by the fall of the ‘state socialist’ countries. They express contradictory elements in the politics of twentieth century Stalinism: the support for movements overseas that were pursuing goals of democracy and national liberation, which the Soviet Union itself denied to the peoples of Eastern Europe. Protestors in Kyiv thus shared with Putin the association of this icon with Russian chauvinism and the state’s hierarchical power. They simply disagreed with him that it was ‘a good thing’.

In Ukraine, insofar as socialist icons have a contemporary meaning, they have become associated with the domination of a Russian “big brother”. Yet, importantly, they are also simply identified with an archaic, indeed “dead”, past experience. This allows the EU to appear as the vehicle of change, modernization, and progress. Indeed, when I visited the main site of the protests at Independence Square, the Ukrainian national flag appeared prominently, but so too, in almost equal measure, did the Flag of Europe, the insignia of the EU. The novelty of this is really quite extraordinary and not simply because of the on-going crisis of the Eurozone. It is impossible to imagine Latin American protestors responding in this way to a US-led Pan-American bloc, or, likewise, Asian protestors to a Chinese initiative. As such, it underlines the extent of the “soft power” the EU appears uniquely able to draw on; despite everything, it is a bloc that non-member countries still wish to join.

Complexity of Ukrainian identity

While a national movement emerged in the middle of the nineteenth century, it was only with Ukraine’s incorporation as a distinct national component in a multi-national state, the Soviet Union, that national sentiment could correspond with a state that, initially at least, allowed it free expression. However, after 1928, the Soviet Union launched a ‘Russification’ campaign that repressed expressions of Ukrainian identity. Its long-term consequence was not only the creation of a bilingual majority, it also led to a substantial minority, around 31 per cent, adopting Russian as their native language. These layers, based in the less developed east of the country, came to identify as ‘Russian-speaking Ukrainians’. In recent years, following the Russia-Georgia War, this ‘double-identity’ has been loaded with intense geopolitical significance, because Russia has granted these layers passports and is accused of promoting regional separatism.

This history underscores how Ukraine has for many generations had a sense of national community without having a fully independent nation-state. The fact that Russia, both in its Tsarist and Soviet form, effectively repressed the polity’s self determination means the consciousness of being on the periphery of this greater power fuels anti-Russian sentiment. Yet this also inevitably creates tensions with Russian-speaking Ukrainians. The clearest expression of the latter is the support for the movement from the far right and anti-Semitic, Freedom Party, who are extremely hostile to the Russian minority.

Geopolitical fractures between “East” and “West”

Russia’s semi-authoritarian domestic politics, and its crude use of gas imports to gain leverage inside Ukraine, has provided a more contemporary source of national resentment. Speaking to those who supported the movement, the strong anti-Russian sentiment was quickly manifested. When I said, half seriously and half-facetiously, “it is rare indeed to see barricades form in defence of the EU”, one academic who supported the movement, simply responded, “we are not pro-EU, we are anti-Russian”.

Russian influence cuts to the heart of the recent dispute. Not only did its intervention lead to the suspension of the EU trade agreement, but the former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko was imprisoned for abuse of power for signing an agreement for Russian gas imports that were significantly over-priced. The current government, more closely aligned to Russia, then renegotiated these terms at a lower rate. The message was clear: Russia would provide material rewards if Ukrainians elected the ‘right’ government.

It would be foolish to think similar geopolitical calculations do not influence European policy-makers, but it is also important to recognise the different way in which the latter’s hegemony is constructed. Consent is favoured over coercion, and, viewed in the context of the history of Russian overlordship, the attitudes of protestors towards the EU become unsurprising. The stinging denunciations of state violence against the protests from European and American political leaders will rightly be seen as hypocritical to those familiar with the use of force against the Occupy movement, but it strikes a chord in a country where the identification of the West with democracy is still taken for granted.

Cosmopolitan aspiration

Despite the involvement of the far-right freedom party (whose flags appeared to be a very small element of the protest camp when I visited it), the overall ethos of the demonstration is probably best summarised as ‘liberal internationalist’ in character. The idea of Europe as a ‘family of nations’ plainly resonated with wide numbers and was reflected in the use of European and Ukrainian symbols. As a concept, the nation-state is arguably a historical construction of modern liberalism and so liberal internationalism has always involved the contradiction that these states will often engage in competitive economic and political behaviour. But, as well as recognising this, one also needs to appreciate the positive that, in a European context where the far right have been the principal beneficiaries of the financial crisis, a movement advocating co-operative internationalism has taken hold in a country itself reeling from serious economic woes.

The protestors’ outlook also involves an aspiration towards freedom of movement. Those that I spoke to emphasised the centrality of this principle, guaranteed by the Treaty of Rome, to the value they gave to the process of European integration. The right to move to other countries, to bring your family, to study overseas, and so on, has become, in Britain at least, the most controversial aspect of EU law, but it is by some distance the most progressive. It is all too easy for those inside of ‘Fortress Europe’ to take this for granted, but the perspective is different from those outside ‘looking in’.

Politics and economics of the social movement

Although the three main opposition parties gave support to the movement, the call for mass city-square occupations was initially put out by unaligned networks of activists and journalists. This might be a factor in the size and breadth of the protest, which was really quite staggering. I was not in the country for any of the huge, several hundred thousand-strong marches, but simply visited the permanent occupation of Independence Square, which was itself thousands strong. Huge barricades had been erected at each side of the square that were 7 or 8 feet high with barbed wire running across the top, and entry in and out of the square was only possible through small entrances, each with stewards.

The movement was also visibly well resourced. Not only had a large stage been erected in the centre of the square, but pictures from the stage were also projected onto a huge screen, the like of which would be more familiar to British festivalgoers than protestors. The overall sense created was that this was movement a little like Occupy would have been had it solicited and won support from ‘big business backers’. Yet, at the same time, there was little sign, as far as I could tell, that the protestors were at all affluent. Neither did they seem overwhelmingly young. Paul Mason’s ‘graduates with no future’ were no doubt present but did not seem dominant. There seemed to be a mix of generations.

Ukraine is a country where one in four people live below the poverty line, and you get the sense of that level of poverty even when walking about the relatively prosperous capital Kyiv. The hardship experienced from the fallout of the global financial crisis is clearly a central motivating factor for participants. Yields on Ukrainian-denominated government debt peaked at nearly 18 per cent over the last weeks and its euro-denominated government debt yields have also been above 10 per cent. It is facing an “old style” balance of payments financial crisis with current central bank reserves only covering another three months imports – a level that the IMF defines as “critical”.

The situation in Ukraine, therefore, provides pause for reflection in terms of how the economic crisis in southern Europe is all too often perceived in simplistic terms as a “crisis of the euro”. Exit for a country like Greece would be very likely to produce a balance of payments crisis such as the one Ukraine is experiencing. Yet in the same vein, Ukraine’s entry into a free market area with the EU would mean its domestic industry had little protection against the much more competitive industries of the German core. The assumption of the pro-EU wing of the political and business elite, that EU investment would have a benign character in contrast to the corrupt and clientelist interests of Russian businesses, does not stand up for scrutiny given southern Europe’s crisis.

This cuts to the heart of the peculiarities of Ukraine’s #EuroMaidan movement. It is partly a militant demonstration with a not dissimilar spirit to the global ‘city square’ movements, and equally propelled by anger at austerity, poverty and joblessness. Yet this element is juxtaposed with a much more populist complexion which can be seen in the advocating of economic demands that favour, rather than cut against, elite interests. Ultimately, in Ukraine as in Greece, these “solutions” treat labour as a commodity that needs to be devalued to create competitiveness, regardless of the human implications.

It is true that a more human response to austerity economics has to cut against market logics. But, in doing so, the Ukrainian movement provides another reminder of the danger of retreating into the dead-end of ‘national solutions’. The cosmopolitan and internationalist element of the protest provides lessons to all of us. Indeed, at a time when both the left and the right appear to be toying with a return to national protectionism, a mass movement rekindling hope in the idea of ‘Europe’ should be warmly engaged with.

Luke Cooper is an Assistant Professor in International History at Richmond the American International University in London. This article was first published by the New Left Project.

2 comments

2 responses to “Lineages of Ukraine’s Civic Revolt”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

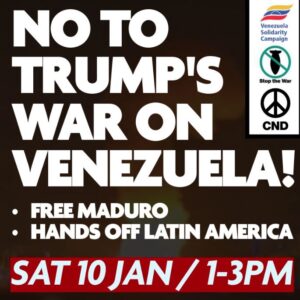

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Comrades

Any serious person should be asking questions about both “sides” in the argument about whether Ukraine comes under the sway of the EU or of Russia. On the pro-EU side there are a series of political forces like Svoboda “freedom” which is extremely right wing, notoriously anti-semitic and more or less fascist; the new party of the boxer Klitschko which is effectively funded and supported by the German CDU and the Ukrainian “Fatherland” Party of Yulia Tymoshenko which is an affiliate of the European Peoples Party (the Christian Democrats with the CDU as the core). Besides the European Tories these forces are also supported by the US and count John McCain as a key supporter. the programme of this crew is the imposition of a savage programme of austerity on the population of Ukraine at the behest of the German Government. The other “side” around Yanukovich is tied to Russia as most of the industrial eastern part of Ukraine is effectively integrated into the Russian economy. This has made Yanukovich and many of his cronies absurdly rich. However, they can pose as having some interest in the Ukrainian working class as Yanukovich does not want to immediately destroy most of Ukrainian industry which is effectively the programme of the crew being promoted in the article. Surely the only real conclusion is that neither of these forces has anything to do with the interests of the Ukrainian working class and the requirement is for an independent party of Ukrainian socialists which would of course face persecution from both sides as all the forces involved are profoundly reactionary.

Matthew is right to draw attention to the involvement of extreme right wing and fascist organisations in the Ukrainian events. Any genuine ‘civic revolt’ to borrow Luke’s term would only be supportable if it chased away these vile elements. I see no sign of this happening.

There is some good pictorial evidence on this libertarian communist website of the extent of fascist and neo-Nazi involvement: http://libcom.org/news/neo-nazis-far-right-protesters-ukraine-23012014

Although I favour Matthew’s analysis to Luke’s, I do think that the light touch moderation on our forum should have be deployed here to change, “Any serious person should be asking questions ..” to say, “Any serious commentary should be asking questions ..” – there’s no need for any resort to ad hominem rhetoric in political discussions between comrades and, if not checked early, such practice can escalate and poison debate.