Leaflet: Remain – For a Europe of Solidarity

This leaflet sets out a case for remaining in Europe, from a left perspective – worker protections, human rights, migration and TTIP.

This leaflet sets out a case for remaining in Europe, from a left perspective – worker protections, human rights, migration and TTIP.

Order printed copies:

Materials are free, but we ask for a donation to cover postage (suggested donation is £2 for smaller orders and £4 for larger ones). Please email office@leftunity.org with your order and mailing address.

12 comments

12 responses to “Leaflet: Remain – For a Europe of Solidarity”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

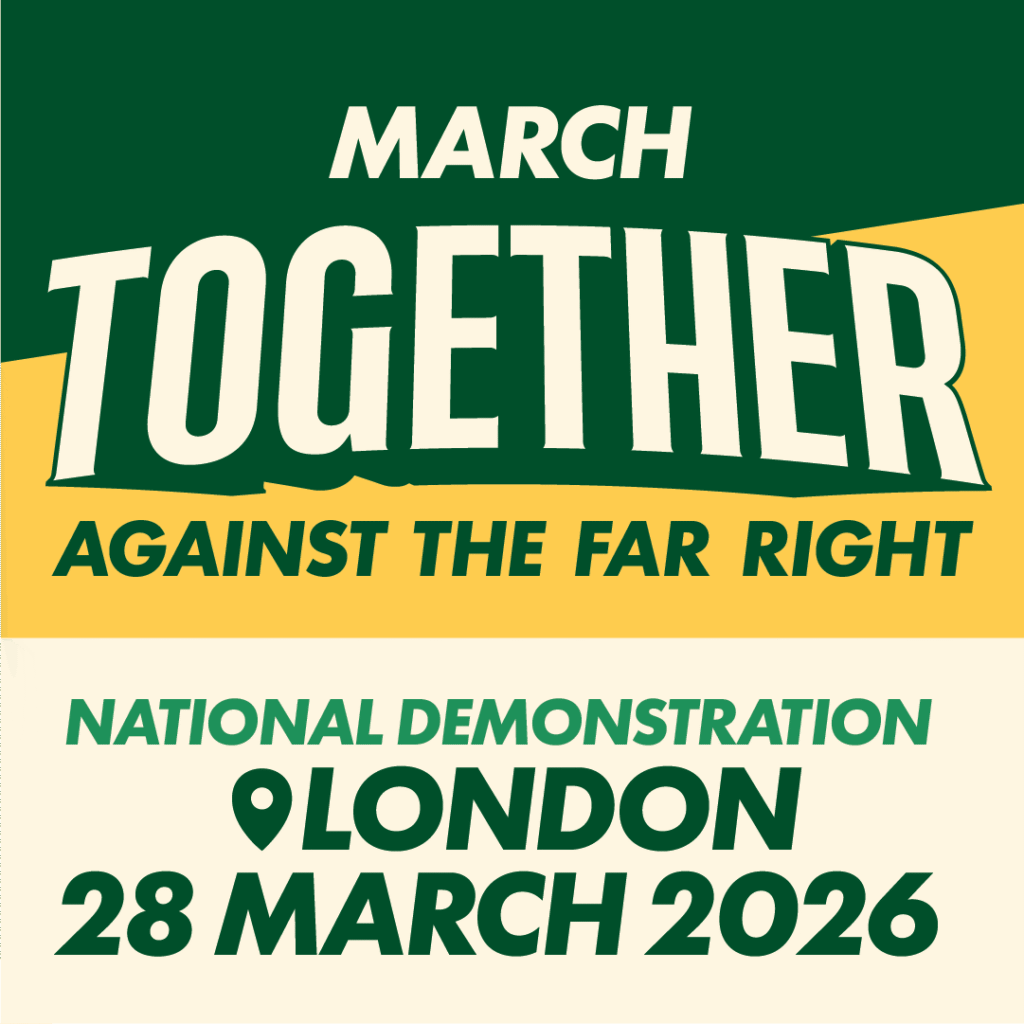

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

The EU is an entirely anti-democratic, pro-corporate monstrosity. Without it we already had worker protection and human rights – they were hard won. Today we have a widening pay gap and zero hour contracts. Prior to Maastrict (the EU proper) we could already travel freely in Western Europe and even relocate with little restriction. And TTIP is an EU-US ‘trade deal’ on which Cameron’s deal is firmly based. If we vote to stay and thus in favour of Cameron’s deal, then this is also a tacit approval of TTIP (read the document). Lastly, solidarity with the people of Europe has nothing whatsoever to do with Britain’s continued membership of the EU. On ‘Europe’ I’m with Jeremy Corbyn and the only difference is that I am allowed to express my opinion freely.

My understanding is that the Equal Pay Act is thanks to the EU. After it was introduced the UK government tried to limit its affect but lost thanks to European judges.

The Human Rights Act from EU, the Tories want to get rid of it.

The tacit approval argument, which I disagree with, can be applied to Brexit lovers tacitly supporting extreme Tories and UKIP.

You might be right about solidarity and EU but Corbyn is leader of a party that wants to stay.

Our problem is not about in or out but how to change what we have nationally ie Tories with different colour ties.

The Equal Pay Act had nothing to with the EU. It was introduced in 1970 by the Labour government in response to an all-out strike by women machinists at Ford’s Dagenham plant.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equal_Pay_Act_1970

Britain has recognised the European Court of Human Rights since 1953 (two decades prior to joining the EEC) and the Human Rights Act 1998 makes its judgements binding in Britain. This act is British law and has absolutely nothing to do with the EU. The Court itself is a body of the Council of Europe, which has 47 member states including Russia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and Turkey. In fact almost half of its member states are not in the EU.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_Rights_Act_1998

Don’t know where this ‘undemocratic’ stuff comes from.

Members of the European Parliament are directly elected;

members of the Council of Ministers are elected by their

respective national electorates.

The Commission is the executive arm of the EU and,generally,

you don’t elect executives – we don’t elect our home civil service

so why would you expect to elect any other?

We don’t even elect members of the second house in the UK,

and that’s about as undemocratic as you can get but I don’t

hear you outers shouting about that. Why is that?

“Elections change nothing” said Wolfgang Schaeuble on the eve of the Greece elections that brought Syriza to power.

“There can be no democratic choice against the European treaties” said president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker shortly afterwards.

Then, a year ago, when the Greek people overwhelmingly voted ‘Oxi’, the Troika (two parts EU) retaliated by insisting that Greece must accept still harsher neo-liberal measures entirely against the wishes of the people. This is not merely undemocratic – it is indeed “anti-democratic” and “pro-corporate” as I wrote.

I am worried about the fact that it is the extreme right which has pushed for the Referendum and it is they who are at the centre of Brexit!

Leaving the EU I believe would seriously destabilise it and it could lead to a domino effect where the EU breaks up into competing Nation States again with all the chaos that will entail. I see no one gaining out of this except the extreme right in all the European Countries and this could easily push us back into a 1930’s situation!

I do not want to risk another European War when we can fight to reform the EU from within. It will take massive public protest across the Continent, but we are already seeing that, even though our Media is not reporting it! I believe it will grow until the EU is forced to change!

Support for TTIP, in Europe, is starting to crumble we do not need to take the drastic step of breaking away from the largest trading market, with all the economic backlash that would cause, to stop that undemocratic deal.

I recognise the undemocratic way Greece was treated by the EU, especially Germany, but this is because the IMF and World Banks are in control. They would be in even more control if the EU were to fracture and every Country needed yet more loans from them to deal with the economic fall-out of the disintegration of the European Union.

These are the reasons I am voting to stay. We must build an International Movement to protect people’s rights and in the EU there is already the structure in place for that movement to grow.

Voting to leave plays into the hands of the extreme far right who want nothing but conflict and power for their own deluded, racist, agendas. I refuse to give them the ‘win-win’ situation a destabilised Europe would offer them!

I believe the decision to leave or stay is verty difficult and complex.

overall at this time i intend to vote to leave.

here are my reasons:

1. I believe that the e.u. does not and will not reform because they are intent upon closer union and more political control.

2.the many number of members which will continue to increase makes massive compromises innevitable and results in noone getting any thing they would like or need to benefit them.

3.i believe that the bankers and big corporations are now on charge and control governments. Their control does not benefit working people who are unable to get jobs or afford homes. Innequality will continue while we are in the e.u.

4. The e.u. is undemocratic and not accountable. They behave like an historical monarchy and treat us like serfs. They have made no attempt to publish their accounts. It is our right to know where these billions od pounds go to.

5 ttip would be innevitable.

6 looking to the future i see the e u. Controlling prople like me…the little people more and more and seen as collateral damage. Their policies and laws would become more and more controlling and intrusive.

even so i do believe leaving would bring msny challenges too but at least ee could maintain democracy.

Maggie writes a detailed and valued case case that should be discussed I am trying here to reply to each point.

“I believe that the e.u. does not and will not reform because they are intent upon closer union and more political control.” The EU reflects the very right wing governments elected in European counties, ( including UK) the globalisation process and the ideology of Austerity and neo liberalism Every one of those criticisms apply even more so to Cameron and co

2.”the many number of members which will continue to increase makes massive compromises innevitable and results in noone getting any thing they would like or need to benefit them.”

There will be internal conflicts as rich countries exploit poorer ones. Britain is one of the exploiting richer countries and will some how or other continue to try to exploit in or out.

3.”I believe that the bankers and big corporations are now on charge and control governments. Their control does not benefit working people who are unable to get jobs or afford homes. Innequality will continue while we are in the e.u.”

The bankers and the very rich are in charge in or out We have to, with all our European working class allies, change the system across Europe

4.” The e.u. is undemocratic and not accountable. They behave like an historical monarchy and treat us like serfs. They have made no attempt to publish their accounts. It is our right to know where these billions od pounds go to”. This reflects what happens here too in or out. The accountancy of our government if far from transparent.

5″ ttip would be innevitable.” TTip is being fought massively by big campaigns in Europe as well as in the UK

6″ looking to the future i see the e u. Controlling prople like me…the little people more and more and seen as collateral damage. Their policies and laws would become more and more controlling and intrusive.”

The little people will be just as damaged by Cameron and co. UK workers have taken a bigger hit to their wages than have other countries except Greece.Together with campaigners in Europe we are stronger to defeat them

“even so i do believe leaving would bring msny challenges too but at least ee could maintain democracy”Yet a brexit government would make appalling treaties as this government and Europe do now.

In or out our future lies in building a huge campaign for socialism with people in the UK and beyond.

This is a good leaflet which we should distribute in large quantities.

I have only one criticism – the reference to “our economy” is fundamentally incorrect. The British capitalist economy is not “ours”, it is privately owned. The socialisation of it, together with the global capitalist economy that it is part of, is the nub of the fight that socialism is all about.

To avoid errors like this occurring in future LU leaflets, drafts should be circulated to branches for review before publication in future.

I strongly agree with John when he says LU publications should be circulated to branches prior to publication. It is a bit much to expect members and supporters to distribute text they cannot fully endorse.

Some of the arguments put by those who want the UK to leave the EU are very rational, just misguided. Many who want to vote to leave are not racist and are not going to be brought on board if they feel they are being accused. Integrity is lost with phrases that start “Anyone who thinks that…” and end “will be sadly disillusioned”. Then there is how patronizing that sentence reads. Is this leaflet designed to be read by anyone other than LU members and supporters?

NOTE! Europe is not the EU. They are two completely separate and different entities, one geographical and social, the other economic and political. This leaflet treats the two as synonymous in the first few paragraphs – thanks to James B for pointing out the members of the Council of Europe – and then goes on to mislead readers by suggesting that hard won struggles helped by solidarity with peoples of Europe have been made possible by EU membership. Solidarity across Europe is built in spite of the EU and its rulings!

The marginal benefits of ‘freedom of movement’ for anyone without a disposable income are surely far outweighed by the union busting EU legislation that we serve under. Since when does, say, finding a better paid position on a 6 month contract 1200 miles away from home ever benefit someone’s family life, their community, or their health? My answer would be when that individual lives an already reasonably comfortable life, not when they make that move by necessity. So, again, who is this leaflet aimed at?

The leaflet could have been a real myth-buster. The emotion could have been taken right out of it, and some facts laid out plainly, as to what exactly the EU has done for us, the people. This would have been no small task; facts are hard to come by where EU institutions treasure their walls of bureaucracy. Still, the opportunity to really challenge the undecided voter by presenting an evidenced leaflet has been lost.

Those rallying to Remain need their own myth-busters like James B, who could improve his evidence by using less spurious sources than Wikipedia but who at least offered evidence!

I think it is perfectly possible to be an opponent of the EU in principle and to not favour leaving at this juncture. The has to do with the current balance of class forces in Britain and indeed the EU (and Europe) as a whole. The leaflet is right to emphasise that Britain leaving the EU at this stage will provide a spur to the racist reactionaries in UKIP and the Tory right: after all, the referendum was their project and their winning will have validated it. It is difficult to know what will happen if they do win, but I wouldn’t like to be one of the 2 million migrants from the EU in Britain. The situation for ethnic minorities in the country could well get markedly worse as well. In addition, a Brexit will encourage the xenophobic right in the whole of the EU.

Some may argue “look what happened to Greece”. There, the situation has been completely different (whether it is now, after last year’s defeat, is a moot point). Leaving the euro (and therefore the EU) as part of the fight against austerity, which was a distinct possibility for Greece last year, would have been a step forward in the class struggle there and in Europe as a whole. I can’t see Britain leaving as a result of a referendum whose main content boils down to hostility to “foreigners” as any such thing.

Women Workers’ Rights and the Risks of Brexit (TUC)

https://www.tuc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Women_workers_and_the_EU.pdf

Introduction “In all its activities, the [European] Union shall aim to eliminate inequalities, and to promote equality, between men and women.” Article 8, Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union “The Court has repeatedly stated that respect for fundamental personal human rights is one of the principles of [European] Community law, the observance of which it has a duty to ensure. There can be no doubt that the elimination of discrimination based on sex forms part of those fundamental rights.” European Court of Justice in Defrenne v Sabena 1978 Gender equality is a founding aim of the EU and it is recognised as a fundamental right in EU law. In the years since the UK joined the EU in 1973, working women have gained significantly from this strong underpinning to their rights. EU law has: • Expanded the right to equal pay, strengthened protection from sex discrimination and improved remedies and access to justice for women who have been unfairly treated. • Strengthened protection for pregnant women and new mothers in the workplace and created new rights that have helped women balance work with care and encouraged men to play a greater role in family life too. • Benefited the many women who work part-time or on a temporary basis, improving their pay and conditions and giving them access to rights at work that they were previously disqualified from. If the UK votes to leave the EU, the workers’ rights that are currently guaranteed by EU law will be at risk. Equal pay, sex discrimination and maternity rights are unlikely to disappear but they could be eroded over time as the gains made over the last four decades are reversed. Rights of women part-time workers and temporary workers are under particular threat of repeal because those leading the campaign for a leave vote have directly attacked the directives that underpin them. This report outlines 20 ways in which EU law has improved the rights of working women in the UK and it considers the threat to rights if there is a vote to leave. Equal pay and sex discrimination “Each member state shall ensure that the principle of equal pay for male and female workers for equal work or work of equal value is applied.” Article 157, Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

1. Equal pay for work of equal value Strike action by the Ford sewing machinists in Dagenham in 1968 was the catalyst for British women finally gaining the right to equal pay with their male colleagues. However, the Equal Pay Act 1970 that was introduced had a gaping hole. It did not give women the right to equal pay for work of equal value. Women could only claim equal

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 3

pay if they were doing the same work as men or they were in the same grade as men in their workplace. The Equal Pay Act was effective in getting rid of the obvious discrimination of having a ‘women’s rate’ and a ‘men’s rate’. But it did little to tackle the undervaluation of women’s work (the fact that jobs mainly done by women are often paid less than jobs mainly done by men requiring similar levels of skill, effort and responsibility). In 1957, the founding Treaty of the European Economic Community had required all member states to ensure equal pay between men and women. In 1975, two years after the UK joined, the EU adopted the Equal Pay Directive that made clear that the right to equal pay included equal pay for work of equal value. However, the UK government took no action to amend the Equal Pay Act. Eventually, the European Commission took the UK government to the European Court of Justice,1 which rules on EU law, and it was forced to amend the Equal Pay Act to comply with the Directive.2 The Equal Pay Amendment Regulations were introduced to parliament in 1983 by a drunk and derisory Alan Clark MP who was Conservative employment minister at the time. When challenged on whether he really believed in the improved right to equal pay that he was introducing, he replied: “a certain separation between expressed and implied beliefs is endemic among those who hold office”.3 Even the Ford sewing machinists benefited from the new right to equal pay for work of equal value. Their initial strike action had succeeded in getting them equal pay with men who were in the same ‘lower skilled’ grade as them. But when the equal value amendments took effect, they pushed for their jobs to be re-evaluated. As a result, they were re-graded as ‘higher skilled’ and they finally got the pay they deserved.4 For many other women lengthy legal battles ensued, with employers defending their discriminatory pay rates every step of the way. One woman among a group of 900 Belfast hospital cleaners who claimed equal pay with the hospital groundsmen, explained how the managers would try to undermine the value of their jobs: “They said that the women cleaned their own homes, so coming in to clean the hospitals is no problem, you know, because that’s what we’ve done all the time”.5 A key case that began in 1986 and took nearly 15 years to settle involved 1,500 women speech therapists in the NHS, supported by their union MSF, who claimed equal pay with the mainly male professions of clinical psychology and pharmacy who earned about £7,000 a year more than them. The UK tribunal and appeal courts that initially heard the claims did not believe that the women had a right to equal pay as they could not show a rule or policy that prevented women from entering the higher-paid, male-dominated jobs, and the courts ruled, if there was discrimination, the employer was justified in 1 Commission v UK (1982) ECJ 2 Equal Pay Amendment Regulations 1983 3 See footnote (9) Equal Pay and the Law by Aileen McColgan. Available at: http://www.unionhistory.info/equalpay/roaddisplay.php?irn=707 4 The Equal Pay Act, its impact on collective bargaining and grading by Sue Hastings. Available at: http://www.unionhistory.info/equalpay/roaddisplay.php?irn=706 5 Interviewed in 2006 for TUC’s equal pay archive. Available at: http://www.unionhistory.info/equalpay/display.php?irn=620

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 4

paying the women less because their pay was set by different collective bargaining arrangements. The turning point came when the case was referred to the European Court of Justice in 1993. The ECJ disagreed on both points and the speech therapists eventually won equal pay.6 The speech therapists’ case opened the door to many more equal pay for work of equal value cases because the ECJ had confirmed separate collective agreements or pay structures within the same employer could not be a defence to an equal pay claim. In the past decade, there have been more than 300,000 equal pay claims, many based on the right to equal pay for work of equal value.7 This litigation has led to new pay structures being negotiated in the NHS and local government to ensure equal pay in the future.

2. Equal pay for part-time women workers In 1980, a UK tribunal ruled that a woman factory worker who was earning a lower hourly rate than a full-time man in the same job did not have a case under the Equal Pay Act. The case was referred to the ECJ and in its ruling it recognised the difficulties that many women face organising work around childcare and the barriers to working fulltime.8 The ECJ concluded that if considerably fewer women than men worked full-time then paying full-timers more could be discriminatory. In another case in 1986,9 the ECJ gave a stronger ruling that paying part-time workers less is indirect sex discrimination and it can only be justified if the employer shows that it is appropriate and necessary to meet a real need of the business. The original Equal Pay Act made no mention of indirect sex discrimination. But after these cases, UK courts had to interpret the Act to include it. The later ruling also set a high threshold for an employer to cross when trying to justify indirect discrimination.

3. Equal pensions for part-time women workers Pensions had been excluded from the Equal Pay and Sex Discrimination Acts too. But ECJ judgements made clear that pensions should be covered.10 At the time it was quite common for UK employers to require a certain number of working hours before an employee could join a pension scheme. Following ECJ rulings in 1994 in several cases involving access to pensions for part-time women workers,11 the government changed the law to ensure equal access. 12 In 1995, 60,000 part-time women workers in the UK, supported by their unions, began a legal challenge claiming retrospective rights of access

6 Enderby v Frenchay Health Authority (1993) ECJ 7 Ministry of Justice Employment Tribunal Statistics for years 2007/8 up to December 2015 8 Jenkins v Kingsgate (Clothing Productions) Ltd (1981) ECJ 9 Bilka-Kaufhaus GmbH v Karin Weber von Hartz (1986) ECJ 10 Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange (1990) ECJ and Bilka-Kaufhaus GmbH v Karin Weber von Hartz (1986) ECJ 11 Vroege v NCIV Instituut Voor Volkshuisvesting BV (1994) and Fisscher v Voorhuis Hengelo BV, (1994) ECJ 12 The Occupational Pension Schemes (Equal Access to Membership) Amendment Regulations 1995 then ss.62-65 Pensions Act 1995

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 5

to their employers’ pension schemes.13 The UK tribunals and courts that initially heard their case imposed a two-year limit on backdating. However, when their case went to the ECJ it ruled that this was against EU equal pay law and backdated rights could go as far back as 1976.14

4. Better protection from sexual harassment As a result of a revised directive on equal treatment between men and women in 2006, the UK government had to amend the Sex Discrimination Act to introduce a specific protection from harassment, which was defined as behaviour that violated their dignity or created a humiliating or offensive working environment for women.15 Before this change, a woman who was harassed had to claim direct sex discrimination, which meant she had to show that she had been treated worse than a man. This sometimes allowed employers to defend harassment claims by using the ‘bastard defence’, claiming that because they treated both men and women equally badly there was no discrimination. The Ministry of Defence used this defence in a case that went all the way to the Court of Appeal in 2004.16 A woman corporal in the RAF had been on the receiving end of obscene and offensive remarks while attending a training course. The courts said they did not doubt that the remarks were degrading and humiliating to her as a woman but the sergeant who had made them was known to make similarly offensive remarks to men too, so there was no sex discrimination.

5. Shift in the burden of proof in discrimination cases The Sex Discrimination Act was amended in 2001 to implement an EU directive on the burden of proof in discrimination cases.17 It makes clear that once a tribunal has been presented with sufficient evidence to suggest that discrimination has occurred, it is up to the employer to prove that they did not discriminate. This is important because it recognises the difficulties individuals often experience when trying to prove discrimination, especially when employers try and cover up any discriminatory motives, behaviour or practice.

6. No limits on compensation in sex discrimination cases EU law has always required that member states must take all necessary steps to make sure that rights are effective. In 1993, the ECJ ruled in a British case brought by a woman who had been a victim of sex discrimination and dismissed from her job that any financial award must fully compensate for the losses and harm suffered and that interest is payable on it.18 The loss suffered by the woman in that case and the interest payable 13 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/part-time-workers-launch-test-cases-on-pension-rights1582002.html 14 Preston & Ors v Wolverhampton NHS Health Authority and Midland Bank & Ors 15 Equal Treatment Directive (recast) 2006 implemented by Employment Equality (Sex Discrimination) Regulations 2005 and Sex Discrimination Act (Amendment) Regulations 2008 16 Brumfitt v Ministry of Defence (2004) 17 Directive on Burden of Proof 1997 and Sex Discrimination (Indirect Discrimination and Burden of Proof) Regulations 2001 18 Marshall v Southampton and South Hampshire Area Health Authority No.2 (1993)

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 6

was three times the limit on compensation that then existed in the Sex Discrimination Act. The Act was subsequently amended to remove the limit.19

7. Better compensation in equal pay cases In 1998, an ECJ ruling increased the amount of back pay compensation available to women who succeed in equal pay cases.20 There was previously a two-year limit in the Equal Pay Act which the ECJ ruled undermined the effectiveness of the right to equal pay. As a result of this ruling, the Equal Pay Act was changed so that when an employer lies to a woman and conceals a pay gap, delaying her claim, there is no limit on compensation. In all other cases, the two-year limit was increased to six years.21

8. Protection from post-employment victimisation In a British case that went to the ECJ in 1998, a woman who had been dismissed from her job while pregnant and complained of sex discrimination found she was unable to gain new employment because her former employer refused to provide a reference.22 The ECJ said that she must be allowed to bring a claim of victimisation against her former employer. Otherwise, sex discrimination rights would not be effective if women were afraid to complain for fear of the consequences. The Sex Discrimination Act was then interpreted to allow for post-employment victimisation complaints and was later amended.23 Maternity and parental rights “Being in the EU underpins much of the protection that pregnant women receive. EU rules, for example, guarantee pregnant women get paid time off to attend antenatal appointments and are protected from being sacked by unscrupulous bosses. These are rights worth protecting, and so long as we remain in the EU they are rights that cannot be taken away.” Cathy Warwick, CEO, Royal College of Midwives24 As with equal pay and sex discrimination, working women in the UK had a right to paid maternity leave before EU law required it and the current entitlement in UK law of 52 weeks’ leave, 39 weeks of which is paid, is much higher than the EU minimum of 14 weeks. But EU Directives and rulings of the ECJ have led to a much more comprehensive set of rights for pregnant women and new mothers in the workplace.

9. Paid time off for ante-natal care The objective of the EU Pregnant Workers Directive introduced in 1992 was to improve the health and safety of pregnant women, new and breastfeeding mothers in the 19 Sex Discrimination and Equal Pay (Remedies) Regulations 1993 20 B. S. Levez v T. H. Jennings (Harlow Pools) Ltd (1998) 21 Equal Pay Act 1970 (Amendment) Regulations 2003 22 Coote v Granada Hospitality (1998) 23 Sex Discrimination Act 1975 (Amendment) Regulations 2003 24 https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/views/why-britain-should-stay-in-europe

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 7

workplace. It led to a number of important changes to UK maternity rights and health and safety law,25 that benefit around 430,000 women workers each year.26 This includes the right to paid time off to attend ante-natal appointments, a key right that many expectant mothers now take for granted.

10. Better health and safety protection for pregnant workers The Pregnant Workers Directive also led to new duties requiring employers to assess the specific risks to pregnant women and new mothers in the workplace. It obliges them to make adjustments to working hours or conditions where there is a risk of harm. Where it is not possible to make adjustments, a woman has a right to be moved to a suitable alternative job or, if there is no suitable job, then she has the right to a paid suspension from work. It also created a specific right to be taken off night work if this is damaging to a woman’s health. Prior to these changes in UK law, the employer had a right to dismiss a woman who could no longer carry out her normal duties because of pregnancy where there was no suitable alternative work available for her.27

11. Better protection from unfair dismissal because of pregnancy The Pregnant Workers Directive also includes a prohibition on the dismissal of pregnant workers or those on maternity leave. As a result, UK law was changed to make dismissal for any reason connected with pregnancy or maternity automatically unfair and the protection applies from day one of employment.28 If the standard qualifying period for unfair dismissal applied to pregnancy or maternity cases today, about a fifth of the women workers who become mothers each year (around 80,000) would be excluded from this protection.29

12. Better protection from pregnancy and maternity discrimination In 1987, a British woman was dismissed because she was pregnant and tried to challenge her dismissal as sex discrimination. Her case went all the way to the House of Lords and, at every stage, the UK tribunals and courts said that she had not suffered discrimination under the Sex Discrimination Act because a man who was going to be absent in similar circumstances would have been dismissed too. However, the case was referred to the ECJ and, in 1994, it ruled that as pregnancy is a condition particular to women, treating a woman unfavourably because of it was direct sex discrimination and it was not permitted by the Equal Treatment Directive.30 UK tribunals and courts then ruled in another case, initiated in 1991, that dismissal of a pregnant woman because of a pregnancy-related illness was not sex discrimination

25 Management of Health and Safety at Work (Amendment) Regulations 1994 and Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act 1993 26 Based on number of women in employment with a child under 1 year old from Labour Force Survey, October – December, 2015 27 S.60 Employment Protection (Consolidation) Act 1978 28 S.24 Trade Union Reform and Employment Rights Act 1993 29 Based on number of women in employment with a child under 1 who have less than two years’ service with their employer, LFS Oct-Dec 2015 30 Webb v EMO Cargo Ltd (1994) ECJ

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 8

because a sick man would have been treated in the same way. When it reached the House of Lords, it referred the case to the ECJ. And, it took the ECJ in 1998 to explain that “pregnancy is a period during which disorders and complications may arise that compel a woman to undergo strict medical supervision and, in some cases, to rest absolutely for all or part of her pregnancy”. It added that “those disorders and complications form part of the risks inherent in the condition of pregnancy and are thus a specific feature of that condition”. And concluded that the Equal Treatment Directive did not allow “dismissal of a female worker at any time during her pregnancy for absences due to incapacity for work caused by an illness resulting from that pregnancy.”31 There is now a standalone definition of pregnancy or maternity discrimination in the Equality Act 2010 which does not require any comparison with a ‘sick man’. It should be noted too, that the European Commission is currently consulting on a potential new package of family-related rights, including stronger protections from dismissal on grounds of pregnancy or maternity.32

13. Right to parental leave Parents of young children gained the right to take up to 13 weeks’ leave to care for a child when the Parental Leave Directive was implemented in the UK in 1999. The Directive was based on an agreement negotiated between trade unions and employers at EU level. UK workers had initially been excluded from its benefits because successive Conservative governments had opposed its introduction and John Major had negotiated an opt-out from the Social Chapter of the Maastricht Treaty in 1993. In 2008, the agreement underpinning the Parental Leave Directive was renegotiated by trade unions and employers at EU level. This resulted in an improved entitlement to 18 weeks’ leave per child which was implemented in 2013 in the UK.33 The coalition government further improved the right so that it can now be taken up to a child reaching the age of 18. Some 8.3 million parents in the UK are now eligible for the leave.34 A government survey in 2012 found that one in ten working parents had taken leave in the previous year, despite the fact that it is unpaid in most workplaces.35 It also found that single parents, 90 per cent of whom are women, are most likely to use this leave. One in five single parents had relied on parental leave in the previous year to help them manage work with childcare – that would be 200,000 of the 1 million single parents who qualify for the leave today.36

31 Brown v Rentokil Ltd (1998) ECJ 32 http://ec.europa.eu/justice/gender-equality/economic-independence/economicgrowth/index_en.htm 33 The Parental Leave (EU Directive) Regulations 2013 34 Based on the number of employees with one year’s service with their employer and a dependent child under 18, LFS Oct-Dec 2015 35 BIS Fourth Work-Life Balance Employee Survey 2012 36 Based on number of single parents in work with a child under 18 and 1 year’s service with their employer, LFS Oct-Dec 2015

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 9

14. Support for equal parenting The Parental Leave Directive recognises that measures to enable workers to balance work and family are central to promoting women’s employment opportunities. It also recognises that encouraging men to participate more in family life is key to achieving the Treaty aim of promoting equality between men and women. When the Directive was implemented in the UK, men gained a right to take time off work to care for a child for the first time.37 When trade unions and employers renegotiated the Parental Leave Directive in 2008, the issue of improving fathers’ take-up of leave was central to the discussions. The revised Directive emphasises the need for leave not to be transferable and the importance of pay in ensuring take-up of leave by fathers. The ECJ is beginning to play a role in improving fathers’ rights to leave too. In two recent cases from Spain and Greece it has ruled that only giving fathers rights to time off when they have an employed partner is sex discrimination.38 And the European Commission’s current proposals for a new package of rights on work-life balance promises to look again at fathers’ take-up of leave,39 which could strengthen pressure for more equal parenting in the UK. Since 2011, mothers in the UK have been able to transfer some of their maternity leave to their partner, first under Additional Paternity Leave and, since 2015, under Shared Parental Leave. But take up of this extended leave by fathers has been very low40 due to the very low statutory pay available (around half the weekly wage for a fulltime worker paid the minimum wage) and because it depends on the mother cutting short her maternity leave and transferring it. The TUC also estimates that around twofifths of working fathers are excluded from this extended right to leave, mainly because of the requirement that their partner must be in paid work.41

15. Time off for dependants The Parental Leave Directive included a right to reasonable time off to deal with an emergency like a family member falling ill or care arrangements breaking down. This right is used by one in five employees a year (that’s 5.3 million), including one in four working parents and three in 10 carers.42 The European Commission has included carers’ leave in its proposals for new measures on improving work-life balance that it is currently consulting on.43 This would really benefit the 3 million working carers in the

37 Paternity leave – the right to two weeks off following a birth – was not introduced in until 2002 38 Roca Alvarez v Sesa Start Espana ETT SA (2011) and Konstantinos Maistrellis v Ypourgos Dikaisosynis (2015) 39http://ec.europa.eu/smartregulation/roadmaps/docs/2015_just_012_new_initiative_replacing_maternity_leave_directive_en.p df 40 https://www.tuc.org.uk/workplace-issues/just-one-172-fathers-taking-additional-paternity-leave 41 https://www.tuc.org.uk/workplace-issues/work-life-balance/employment-rights/two-five-newfathers-won%E2%80%99t-qualify-shared 42 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32153/12p151-fourth-work-life-balance-employee-survey.pdf 43 http://ec.europa.eu/smartregulation/roadmaps/docs/2015_just_012_new_initiative_replacing_maternity_leave_directive_en.p df

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 10

UK.44 For while the last two decades have seen real improvements in the rights for working parents, working carers in the UK – 3 in 5 of whom are women – still have few rights to time off.

16. Protection from discrimination for carers Carers gained protection from discrimination in the workplace when the ECJ ruled in a case involving the British mother of a disabled child that those caring for disabled people should be protected from discrimination.45 The mother had been harassed and treated badly by her employer because of the time off she needed to care for her son. The Equality Act 2010 now allows carers to bring discrimination claims on the basis of an association with a disabled person. Women working part-time and on a temporary basis Unequal patterns of care and the difficulties of juggling work with care mean that women’s work choices are often more constrained than men’s. This means women are far more likely to work part-time – three-quarters of part-time workers are women. Women are also more likely to be on temporary contracts – women make up 47% of the whole workforce but 55% of fixed-term employees are women.46 Traditionally, part-time and temporary workers have been seen as peripheral and way of an employer gaining extra flexibility and avoiding the costs and responsibilities of employing full-time, permanent staff. As a result, these marginalised workers, often women, had worse pay and conditions and were denied rights that those in the ‘core’ workforce enjoyed. The steps taken at EU level to improve the pay and conditions of part-time and temporary workers have benefited millions of working women in the UK.

17. Equal rights to unfair dismissal and redundancy pay for part-timers UK law used to require a person who was working between 8 and 16 hours a week to have 5 years’ service before they could claim unfair dismissal or statutory redundancy pay. A person working less than 8 hours a week was completely disqualified from these rights. By contrast, a full-time employee had to have two years’ service. The former Equal Opportunities Commission took the Conservative government to court to challenge these rules using EU law. Eventually, in 1994, the House of Lords agreed that they were sex discriminatory and did not comply with EU equality rights.47 Against its belief that granting these rights to part-time workers would threaten growth in part-time jobs, the government was forced to change the law.48 If it had not changed it, 530,000 part-time workers today would not have access to these basic protections at work.49

44 https://www.carersuk.org/for-professionals/policy/policy-library/facts-about-carers-2015 45 Coleman v Attridge Law (2008_ 46 LFS, Oct-Dec 2015 47 R v Secretary of State for Employment ex parte Equal Opportunities Commission (1994) 48 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1994/dec/20/part-time-workers 49 Based on number of workers earning under 8 hours a week with more than 2 years’ service and the number working 8 to 16 hours a week with more than 2 years’ service but less than 5 years’ service, LFS Oct-Dec 2015

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 11

18. Paid holidays for part-time workers Those campaigning to leave the EU have often brushed aside concerns about risks to basic rights like paid holidays, saying that most workers in the UK had paid annual leave long before the Working Time Directive required it. It is true that most full-time, permanent employees did have paid holidays before the working time rules were implemented in the UK in 1998. But the workers who had no entitlement to paid holiday were mostly part-time workers and mostly women. At the time of implementation, it was estimated that a third of part-time workers had no right to paid holiday, compared to 4% of full-timers.50 If that were still the case today that would be 2.3 million part-time workers without any right to paid holiday – 1.7 million of whom would be women.51

19. Equal treatment for part-time and fixed-term employees As already explained, part-time women workers made a series of gains by relying on EU sex discrimination and equal pay law. Rights to equal treatment for part-time workers and fixed-term employees were further improved when, in 2000, the Part-Time Worker Directive was implemented in the UK and, in 2002, the Fixed-Term Worker Directive was implemented. Part-time workers gained the right to equal treatment with full-timers without having to show that their less favourable terms and conditions amounted to sex discrimination. This benefited the part-time women workers in female-dominated sectors where they could not compare their treatment to men. Employees on a fixedterm contract gained new rights to equal treatment with permanent staff, including to things like pay, bonuses, pensions and the employers’ maternity benefits. Fixed-term employees also gained greater job security and better access to permanent jobs. As with the Parental Leave Directive, the Part-Time Worker and Fixed-Term Worker Directives had been strongly resisted by successive Conservative governments. The Directives were based on the Social Chapter and were negotiated between trade unions and employers at EU level. This point is relevant today as when Boris Johnson and others call for the social chapter to be scrapped or the UK’s opt-out to be restored,52 these are the rights they are attacking – rights that benefit mostly women.

20. Rights for pregnant agency workers Many employment rights in the UK have been restricted to employees only. At EU level, where equality is considered a fundamental right, a more inclusive approach has been taken. For example, in a recent case, the ECJ said it did not matter how a woman’s relationship with an employer was classified, what was most important was that the protection that existed in EU law was applied to all pregnant workers.53 There is still a long way to go in improving the rights of agency workers both in the UK and EU. But EU law has helped secure some minimum protections for pregnant agency workers in 50 See p.11 and footnote 10 in http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/RP0050/RP00-50.pdf 51 LFS, Oct-Dec 2015 52 E.g. see http://www.thesun.co.uk/sol/homepage/news/politics/4681084/Boris-Johnson-callsBritains-EU-stance-morally-wrong.html 53 Danosa v LKB Lizings SIA (2011)

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 12

the UK. When the Temporary Agency Worker Directive was implemented in 2011, women agency workers gained the right to paid time off for ante-natal appointments and a right to suitable alternative work or a paid suspension if there is a health and safety risk (subject to a 12-week qualifying period). Also, the revised Parental Leave Directive 2010 provides that workers cannot be excluded from rights solely because they are parttime, fixed-term or agency workers. Risks of Brexit This report has shown how the UK’s membership of the EU has led to real and substantial gains in working women’s rights. UK women, trade unions and equality bodies have worked within the EU and used EU law to get rules that discriminated against women overturned and to secure new rights that place women on a more equal footing. If the UK votes to leave the EU, some of the gains that have been made on women’s rights could be reversed and the opportunities to make further advances will be lost.

1. Narrowing the right to equality Few nowadays would argue that women do not deserve equal pay or that sex discrimination should not be illegal. But rights to equal pay and equal treatment in the workplace could be narrowed so they apply to fewer situations and benefit fewer women. Some of those on the right, who are campaigning for the UK to leave the EU have a very narrow view of equality. They accept that where a woman acts like man, she should be treated equally, or where a woman is doing exactly the same work as a man she should get equal pay. But if a woman has a baby, takes time out of the workplace, reduces her hours, or chooses to do a job seen as ‘women’s work’, then she has no right to expect equal pay or the same opportunities as men. UKIP leader Nigel Farage told a mainly male audience in the City of London in 2014 that he did not believe there was any sex discrimination at all and that young women who are prepared to sacrifice family life and stick with their career could do as well as, if not better than men. “In many cases women make different choices in life to the ones men make, simply for biological reasons. A woman who has a client base, has a child and takes two or three years off – she is worth far less to her employer when she comes back than when she went away because that client base won’t be stuck as rigidly to her portfolio.” UKIP leader, Nigel Farage54 The history of litigation on equal pay, sex discrimination and maternity rights also shows the deeply ingrained prejudices about the value of women’s work and what equality means in practice. As has been shown above, UK law and UK judges failed numerous times to recognise that equality can mean treating women differently. It can mean questioning how jobs are valued, changing workplace practices to prevent women being disadvantaged and taking positive steps to meet the specific needs of women, particularly as mothers and primary carers. It was the strong underpinning of EU law

54 http://news.sky.com/story/1197923/farage-working-mothers-worth-less-than-men

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 13

and the recognition of gender equality as a fundamental right that helped secure many of the advances in working women’s rights in the UK in the past four decades.

2. Exempting businesses from the ‘burdens’ of equality A major threat to all EU-guaranteed rights for workers after a possible Brexit is the drive from successive UK governments to deregulate the labour market and reduce ‘burdens on business’. The costs to business of complying with employment laws is emphasised over everything else and there is little attempt to quantify the benefits to workers or society. During this referendum campaign, for example, Michael Gove has said that outside the EU we would not have to follow all the EU regulations that cost UK businesses £600 million a week.55 This figure is based on a report from Open Europe of the 100 most costly EU regulations.56 In third place on that list is the Working Time Directive – the directive that means 1.7 million part-time women workers have a right to paid holiday. This directive is reported to cost £4 billion a year, while the benefits are reported as zero. The amendments to the Sex Discrimination Act that resulted in improved protection from harassment in the workplace also feature on the list, costing £178 million a year, and again, the benefits are reported as zero. Similarly, the EU right to parental leave is reported to cost £60 million a year but its benefits are, again, zero. To emphasise that equality rights are unlikely to be safe from a deregulatory government: in 2011, the government launched a Red Tape Challenge looking for “unnecessary regulations” to cut and the Equality Act 2010, which now contains the right to equal pay and protection from all forms of discrimination, was one of the first pieces of legislation to feature on the RTC website. This was despite the fact that the Act had just been passed by parliament with cross-party support and after years of consultation with employers, trade unions and others. Of course, much of the Act is required by EU law so the government’s deregulatory zeal had to be reined in. However, it eventually found some things to cut from the Act: the statutory questionnaires that workers could use to ask their employer about equal pay and discrimination in the workplace (these had been a feature of UK discrimination law since the 1970s); the specific protection from harassment by third parties; and the wider powers for tribunals to make recommendations following a finding of discrimination to prevent others suffering discrimination. The ‘burdens on business’ argument is also frequently used to argue for more exemptions to workers’ rights. For example, in 2012, the review of employment law that David Cameron commissioned from venture capitalist Adrian Beecroft recommended that small businesses should be excluded from shared parental leave. He described maternity and parental leave rights as “well meaning” but concluded that for small businesses “the price was not worth paying”.57 David Cameron also set up a business taskforce to make recommendations on cutting EU red tape which, in 2014, recommended that the starting point for all new proposals on workers’ rights should be 55 http://www.voteleavetakecontrol.org/michael_gove_s_oped_for_bbc_radio_4_today_programme 56 http://openeurope.org.uk/intelligence/britain-and-the-eu/top-100-eu-rules-cost-britain-333bn/ 57 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/employment-law-review-report-beecroft

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 14

that micro businesses are exempt. At present, this would not be possible under EU law but if it was ever followed it would mean a third of the workforce being excluded from rights.58 The taskforce also singled out EU proposals for improvements in maternity rights for criticism saying that they should be dropped completely.

3. Jobs but no rights Closely linked to the ‘burdens on business’ argument is the claim that we need less regulation to encourage job growth. There is a particular variant of this argument that is applied to rights for working women. It was typified by Alan Sugar’s comments in 2008 that equal opportunity laws have made it harder for a woman to get a job.59 And it has been used frequently to argue against EU law intended to benefit working women. For example, in 2010, it was the basis of Conservative MEPs’ case against improved maternity rights. According to Marina Yannakoudakis MEP: “Stricter EU rules on maternity leave will make it harder for women of child bearing age to get work”.60 As the TUC pointed out at the time to MEPs involved in the debate, the evidence points in the opposite direction in the UK: as maternity rights have improved over the last two decades, women’s employment has too. This argument was also used by the Conservative government in 1994 when being forced to introduce equal rights for part-time workers to claim unfair dismissal and redundancy pay. The government was convinced the new rights would threaten existing part-time jobs and hold back growth in part-time employment. The EU’s proposals for the Part-Time Workers Directive were attacked at the same time too: “The priority for Europe should be tackling unemployment rather than adopting further costly social legislation which increases burdens on business and destroys jobs”. Michael Portillo MP, Employment Minister, 199461 As it happens, since part-time workers gained more rights, the proportion of the workforce that is employed on a part-time basis has grown. But the argument that EU social rights are bad for jobs persists today: “If we could just halve the burdens of the EU social and employment legislation we could deliver a £4.3 billion boost to our economy and 60,000 new jobs.” Priti Patel MP, Employment Minister and Vote Leave campaigner, 201662 So without the guarantees that EU law provides, women could face a future in which they are expected to be grateful to have a job and should not expect rights to equal treatment, decent pay, job security, maternity leave and parental leave too. This is a 58 http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06152/SN06152.pdf 59 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-513264/Sir-Alan-Sugar-Why-I-think-twice-employingwoman.html 60http://www.marinayannakoudakis.com/euwideincreaseinmaternityleavewilldamagesmallbusiness esandyoungwomensemploymentprospects-181/ 61 http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1994/dec/20/part-time-workers 62 http://touchstoneblog.org.uk/2016/05/let-cats-priti-patel-suggests-lose-half-eu-work-rightsbrexit/

Women workers’ rights and the risks of Brexit 15

particular risk for women in small businesses or those in low paid, part-time and insecure forms of work who are in a much weaker negotiating position than those in permanent, well-paid, high skilled or professional jobs.

4. Making rights less effective Post-Brexit, a deregulatory government could just leave working women’s rights in tact on paper but make them less effective in practice. The government has already pursued this approach with the introduction of employment tribunal fees in 2013. In its election manifesto for 2015, the Conservative party boasted of “reducing the burden of employment law” with its tribunal reforms.63 Unison is currently challenging the introduction of fees, arguing that they go against the EU principle that rights must be effective – since fees were introduced, sex discrimination claims have fallen by 76%.64 So far, Unison has not been successful in its challenge, but the case will be heard in the Supreme Court in December 2016.65 Cutting compensation in discrimination and equal pay claims would be a very likely target too. The Beecroft Review recommended re-imposing limits on discrimination awards and the government recently reduced the amount of compensation available in unfair dismissal cases, which is not covered by EU law.

5. Fewer opportunities for future gains Finally, if the UK were to leave the EU, there would be far fewer opportunities for future gains. Women trade unionists from the UK would lose opportunities to work alongside sister organisations from other countries to campaign and negotiate for better rights within the EU. UK courts would no longer be bound to interpret UK law in line with EU law. Women workers in the UK would be denied the opportunity to seek a referral of a case to the ECJ on whether there had been a breach of EU law. Any future progressive judgements of the ECJ on issues that affect women in the workplace could be ignored. As the leading employment law barrister, Michael Ford QC has explained in his advice to the TUC on the impact of EU law on workers’ rights: “It is difficult to overstate the significance of EU law in protecting against sex discrimination. The ECJ has repeatedly acted to correct decisions of the domestic courts which were antithetical to female workers’ rights: a history could be written based on the theme of progressive decisions of the ECJ correcting unprogressive tendencies of the domestic courts.” Michael Ford QC, Old Square Chambers and University of Bristol66

63 https://www.bond.org.uk/data/files/Blog/ConservativeManifesto2015.pdf 64 Annual Employment Tribunal Statistics, 2012/13 compared to 2014/15. 65 https://www.unison.org.uk/news/press-release/2016/02/unisons-battle-to-scrap-employmenttribunal

Conclusion: Don’t risk it Vote Leave campaigner Priti Patel MP compared women campaigning for Brexit to Emmeline Pankhurst and the other suffragettes. She said they did not fight for the right to vote to see “those decisions surrendered to the EU’s undemocratic institutions and political elite” and that leaving the EU would “enhance our democracy and empower women in this country”.67 But, as this report has shown, in many instances it has been rights guaranteed by the EU that have been instrumental in empowering working women, enabling them to challenge unequal pay and to claim equality at work. The UK government has often stood against them, reluctant to allow claims for equal pay for work of equal value, opposed better rights for women part-time workers and blocking improvements in maternity rights at EU level. The EU is not perfect. The rights for working women that the EU now guarantees have been hard won and there are battles ahead. But a vote to leave the EU risks turning the clock back decades and losing many of the gains that have been made. And it risks years of uncertainty as all the rights guaranteed by the EU would be reviewed, legislation amended and case law from the ECJ would be questioned. Helen Pankhurst, great-granddaughter of Emmeline Pankhurst responded to Priti Patel: “My great-grandmother fought tirelessly for women’s rights and dedicated her life to making sure women could live their lives free from discrimination. It is unacceptable to use her achievements to argue for something that is so out of line with the spirit of international solidarity that defined the suffragette movement. To the contrary, I believe that my great-grandmother would have been the first to champion what the EU has meant for women, including equal pay and anti-discrimination laws.” Helen Pankhurst, great granddaughter of Emmeline Pankhurst, March 201668