FIFA – the beautiful game corrupted by profit and greed

Leo Oliveira of Lambeth Left Unity argues the football corruption debacle could be a chance to push back against big money’s influence in sport

The only shocking thing about the arrest of 14 senior FIFA officials on corruption charges is that it is happening at all. Allegations of corruption have publicly beset the organisation for the past two decades – it was a public joke that FIFA was run by brown paper bags full of money. Now it seems that things have finally come to a head.

Seemingly impervious to any form of accountability, the revelations that corrupt practices are “systemic and deep-rooted” within football’s world governing body have now precipitated the resignation of its much-maligned president Sepp Blatter, purportedly under investigation himself – though he won’t actually step down until December.

With Blatter deposed and the prospect of authorities finally undertaking concerted action to cleanse the organisation, there is widespread hope that this heralds the opportunity to rebuild FIFA afresh. But for many people, including those who football is of no interest to, the story of corrupt officials at the helm of a transnational organisation is nothing new. So why should this FIFA debacle be of interest to the left?

Answering this question lies partly in recognising that FIFA is more than just another profit-making vehicle for corporations willing to turn a blind eye to nefarious backroom dealings. In order to realise its mission of spreading football to all corners of the globe, FIFA has relied on the ready cash of corporations who have gladly seized the opportunity to have access to its structures in order to commodify – and make a huge profit from – the game.

This has engendered an unresolved tension within FIFA between allowing developing nations to benefit to an extent from the redistribution of sponsorship money to national football associations, and the creation of an almost feudal, vassal-like relationship that facilitates corrupt practices.

Just as corporations have used FIFA as cover to create a burgeoning market from which to extract profit, so too have national political elites recognised its potential. Under the pretence of bringing football back to its spiritual home, preparations for the 2014 World Cup in Brazil acted as justification for displacing whole communities. Riots sparked across Brazil as the poor Favelas were cleared to make way for luxury hotels and to “tidy up the city” for foreign visitors.

But if the excesses of modern day capitalism were exposed, so too were its inefficiencies. Fitzcarraldian delusions were enabled, leading to the building of stadiums never to be used again. But these themes are not isolated to non-Western World Cup host nations like Brazil, Russia or Qatar. The dubious Olympic legacies of Sydney, Athens and London are testament to how the disconnect between fans and the executives has allowed transnational sporting bodies to be bought and sold to the highest bidder in order to provide the veneer of respectability to massive redevelopment projects that come at the expense of so many.

In addition, the effect of FIFA’s corruption on football fans’ experience is also felt in subtler ways. Corruption, and the relations of power it engenders, has proved to be a disincentive to action for FIFA executives who are ultimately responsible for the world game. Better to pay lip service to progressive sounding, yet ineffective, FIFA campaigns set up to investigate match fixing or combat racism than risk one’s little fiefdom.

And yet, despite fans’ awareness of corruption at FIFA, the global popularity of the game continues to grow unabated. This provides credence to the perception that modern football culture has adopted the mantle of the people’s opiate. However, the standards of accountability applied to the game by fans are rooted in personal gratification. Viewed through a prism of Berlinian ‘negative freedom’, this contrasts with the public standards of accountability to which corrupt elites within the political classes are held.

Rather than being an apoliticising force, football has provided an avenue for individuals’ continued engagement in a public arena, albeit a hermetically controlled one, at a time when neo-liberalism has accelerated the democratic deficit and fractured labour movements globally, thereby creating individuals divorced from the political sphere.

Fans’ lived experience in dealing with issues such as racism, homophobia, increased ticket prices, the question of club ownership, police brutality and fixed matches, to name but a few salient issues within the modern game, have led to instances of resistance. In Britain campaigns aimed at reforming football or creating alternative cultures and structures have started to proliferate.

However, we need only look at the protests against the 2014 World Cup that took place inside football grounds and in the streets across Brazilian cities to see that fans can transform resistance into conscious political demands as they linked the damaging processes they were subjected to, in the name of hosting a World Cup, with their social and political grievances.

Another case in hand is that of Egyptian football ultras, whose prominent involvement in the 2011 revolution emanated from their previous experiences at the hands of the regime’s security forces.

This points to an unresolved tension inherent to modern football in which supporters’ experience of their negative freedom is itself being squeezed, primarily by the vagaries of the market whose intrusion into the game has been facilitated by FIFA. The left should, therefore, aim to link up, where appropriate, with supporter groups resisting the onslaught of changes to the game (and the lack of changes, in the case of racism and homophobia, for example) to ensure that campaigns are rooted in an understanding of the structural causes that give rise to injustices.

But the current crisis within FIFA also provides an opportunity for the left to contribute and intervene in the debate as to how it will be restructured. We need to drive profit out of football. The game should come before greed. Alongside this, a call to revive FIFA’s internationalist aspirations, which informed its founding in 1904, whilst being critically aware that the formulation of this was undertaken in a world in which there was a strong colonial mindset, should become a central plank in wresting back control of global football away from big money and corruption.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

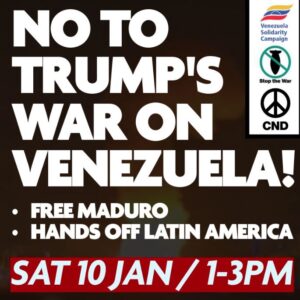

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.