Eyewitness: War in Ukraine

War reporter Hugh Barnes writes from Ukraine: Ukraine lies at the heart of Europe in terms of geography, history and culture, but it is also a post-Soviet state with long-standing ties to Russia. This dual legacy is the pretext for Russia’s genocidal war, but in theory it should be a geopolitical asset. Here is a European country that, uniquely, looks both east and west.

Over the past month I have been travelling between the three main centres of Ukraine’s population and its politics from the western city of Lviv, which was a part of Poland until the Second World War to the former Soviet capital Kharkiv in the east, via Kyiv on the Dnipro river that runs south from the Belarus border into the Black Sea, dividing the country in half. To do so in wartime is dangerous but also illuminating about the history and geography and linguistics of division in a country where the media insists on casting the rivalry between Russian and Ukrainian speakers as a classic bi-polar struggle between Slavophils and Westernisers.

Yet the conflict in Ukraine is full of surprises. Kharkiv has faced round-the-clock bombardment from Russian planes and artillery since the military invasion began on 24th February. The following week, on 2nd March, a cruise missile destroyed the regional government’s headquarters and several other dramatic Constructivist buildings in Freedom Square. It was a stark reminder Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not only a humanitarian catastrophe and a war crime but also a barbaric destruction of our collective architectural heritage. Yet a month into the war, Ukraine’s second city – only 20 miles from the Russian border – is still more or less under government control, an index of how badly the Russian invasion has been going, and also perhaps a grim forecast of how much longer it will have to go on before Vladimir Putin achieves his mysterious objectives.

The ‘special military operation’, as the Kremlin refers to its war in Ukraine, is not only an unprovoked and unjustified attack on a sovereign state. It also poses a dangerous threat to the future of the planet if the conflict escalates into nuclear warfare. On 22nd March, Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov refused to rule out the possibility of using nuclear weapons against Ukraine. It was a back to the future moment: spin doctor meets Dr Strangelove. The Russian president’s incendiary obsession with the bomb sparks fears from a bygone era, just as the murderous siege of Kharkiv has been described by an advisor to Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky as the Stalingrad of the 21st century. On 25th February Putin seemed to offer a pretext for attack, ominously accusing Ukrainian ‘neo-Nazis’ of placing heavy weapons in the centre of Kyiv and Kharkiv, ‘acting in the same way that terrorists act all over the world – using people as shields’. In fact, he is the real terrorist in the present scenario, with his attacks on maternity hospitals and nuclear power stations, but just because the ‘savvy genius’ of the Kremlin is unquestionably deranged when it comes to formulating Russia’s so-called security concerns doesn’t mean that Nato enlargement since 1998 and its continued expansionary plans are not threatening to drag Europe into a devastating war.

It was apparent that a month into the invasion Russian troops had failed to win the quick victory that Putin was counting on. Zelensky, one the other hand, once derided as a comedian out of his depth, had become an international emblem of resistance, especially for young people who see the war in Ukraine as a literal and symbolic instance of the worldwide struggle against dictatorship. But there is a darker side to the story of the war in Ukraine and its impact on a generation of young people reeling from the injustices of the 21st century. Everything is so compromised nowadays: austerity, climate action, brexit, covid, even standards in public life. Is the war in Ukraine any different? When Putin sent the tanks rolling across the Belarus border in the early hours of 24th February, on a mission to kill civilians and overthrow an elected president, the line did seem to be clearly drawn. Good was opposed to evil, democracy to dictatorship, and even though the United States and its Nato allies have stuck with a policy of non-intervention, it is possible for individuals to intervene, and to fight for democracy.

Ukrainian forces continue to harass the invading army, posting images of destroyed Russian equipment. When I was in Kharkiv, one of the Ukrainian guerrilla leaders claimed that a Russian unit had abandoned 10 tanks, although it was impossible to confirm this report. According to Ukraine’s SBU (formerly KGB) security, Russian Spetznaz ‘considered’ blowing up ammonia warehouses in the city and then blaming the inevitable death toll on Kyiv’s armed forces. But again it was impossible to verify if this was true and may just have been ‘pre-bunking’ intelligence to derail a Russian plot. Since the war in Chechnya, which I covered almost a quarter of a century ago, the Russian army has upgraded to such an extent that it may now be capable of annexing eastern Ukraine. Even so, it struggles to overwhelm Ukrainian defenders in critical battles, such as the one in Mariupol on the Sea of Azov. For some reason, Russian generals often go for prolonged sieges, with heavy use of artillery and shelling, as well as Uragan and Smerch rocket launchers, instead of ground assaults. Maybe it’s the professional soldier’s way of cocking a snook at the war criminal Putin because everybody knows, even the lowliest conscript, that Moscow didn’t really have to invade Ukraine to achieve its long-term objective, which is to make sure that its neighbour does not join Nato or associate itself too closely with the European Union.

Skirting between the Russians’ double-pronged advance on Kyiv from the north and also from the southwest Kherson region, while the action in the east centres around Kharkiv, I managed to cross the line of contact separating the two sides in the Donbas and arrive in Yeniakievo, a town approximately 40 minutes northeast of Donetsk, where the ousted former president Viktor Yanukovich was born in 1950.

Yenakievo is a woebegone place, Ukraine’s Coketown, and such a blur of smoke and dirt and neglect that even my Donetsk-born taxi driver struggled to find the road. Yet here the mood was unexpectedly defiant of both sides in this internecine war. Under banners declaring the Donbas to be ‘undefeated’, a few hundred people were demonstrating on the steps of city hall when I arrived. One of the banners quoted Balagur’s old Russian almanack: ‘As the old Cossack said, if Ukrainians are ever ordered to fight the Russians, we should stand on the border, shoulder to shoulder, and shoot at the people giving the orders.’

I had come in search of the owner of the Yenakievsky Coke Plant, Yanukovich’s favourite oligarch, Yuri Ivanyushchenko. I wasn’t expecting to find him – and didn’t, by the way. A former absentee member of Ukraine’s parliament between 2007 and 2014, he continues to spend most of his time in Monte Carlo for fear of arrest, according to his enemies, while his business empire, like those of many Russian and Ukrainian oligarchs, is domiciled in London. He is one of 30 Ukrainians whose assets were frozen by the Swiss government following the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Also born in Yenakievo, but nine years younger than Yanukovich, the all but invisible Ivanyushchenko is a semi-legendary figure who was allegedly the leader of an organised crime group in eastern Ukraine during the 1990s, although he won a libel suit in 2011 against a website that published a leaked dossier on him compiled by Russian intelligence officers who later disowned the document.

The real tragedy of Putin’s war lies in eastern Ukraine, which is divided into three main regions, or ‘oblasts’: Donetsk (including Mariupol), Luhansk and Dnipropetrovsk. Until secession in 2014, the first two were dominated by the Party of the Regions, which Yanukovich used to lead, and perhaps still does. He was backed by the infamous ‘Donetsk Clan’, of business oligarchs who controlled the coal and metallurgical industries in the Donbas industrial heartland. And for quarter of a century, between the fall of the Soviet Union and fall of Yanukovich, the struggle between the Donetsk clan and the rival Dnipropetrovsk clan provided a subtext to political upheaval in Ukraine. It’s the main subplot was the vendetta between Yanukovich and his nemesis Yulia Tymoshenko.

An acquaintance of mine who used to work for the SBU (formerly KGB) refers to Ivanyushchenko by his gangsterish nickname, klichka in Russian — Yura Yenakievsky (literally ‘Yuri from Yenakievo’). Other intelligence and law enforcement officers use another sobriquet for him: Yura Maloy (‘Yura the Kid’).

Until 2014, the Donetsk clan had three leaders corresponding to its three different spheres of activity. Its political leader was Yanukovich, who lived in Yenakievo until he was appointed deputy governor of Donetsk region in 1996. He and Ivanyushchenko were close friends until they fell out with each other a decade ago (another subplot). The clan’s business leader was Rinat Akhmetov of System Capital Management group. The dodgy dossier alleged that Ivanyushchenko was its criminal mastermind. In any case, it may be useful to consider where these three amigos are now – and also where their loyalty resides in the aftermath of 24th February.

People in eastern Ukraine usually speak in hushed tones about the enigmatic Ivanyushchenko. A senior advisor to Yanukovich’s former prime minister, Mykola Azarov, said that Ivanyushchenko belonged to an influential grouping around Ukraine’s ex-president, known as The Old Friends (or, literally, ‘friends from childhood’). A source in the Tymoshenko bloc said that there are three ‘authorities’ in Donetsk, and ‘and they are Seva [Semyon Mogilevich], Yura [i.e. Ivanyushchenko] and Rinat [Akhmetov].’ Yet Ivanyushchenko is very rarely seen in public. Indeed he has been seen in Ukraine only a handful of times since a Yanukovich birthday party, in 2010, which he attended along with Akhmetov, Dmitro Furtash, Valery Khoroshkovsky, Viktor Pinchuk and other powerful oligarchs. A former head of Ukraine’s Interpol bureau, Kirill Kulikov, once said to a friend who asked about Ivanyushchenko: ‘I have heard of him, of course, heard, what he is. But don’t ask me about Yura Yenakievsky because I don’t know. He’s like De Gaulle. You read a lot about him, you hear a lot, but you never see him.’

Ivanyushchenko’s emergence as a powerful figure in Donetsk is best understood in the light of his background as a state enterprise manager – or ‘red director’ – in Yenakievo at the time of the fall of the Soviet Union. As deputy director of the Yenakievo coke plant, Ivanyushchenko was typical of the first generation of Ukrainian oligarchs who emerged from the hyperinflationary aftershock of independence by exploiting control over regional monopolies to misappropriate state credits and tax benefits that enabled them to seize control of industrial assets. The Donetsk clan led by Ukraine’s richest individual, Akhmetov (who has switched sides since February’s invasion) and Ivanyushchenko (who hasn’t) is still one of the most powerful economic entities in the country. It influences virtually all the Donetsk region’s industry, as well as some enterprises in Luhansk and Dnipropetrovsk regions, and has a monopoly control over virtually every aspect of regional life, administration, and industry. Its origins lie in the early 1990s when it emerged as an informal coalition of powerful regional businessmen and politicians that used a series of miners’ strikes to establish itself as a political force.

In the summer of 1993, Ivanyushchenko helped to organise a general strike on behalf of the Donetsk clan that almost paralysed the whole economic system of Ukraine. As a result, the then President of Ukraine, Leonid Kravchuk, dismissed the government of prime minister Leonid Kuchma, who belonged to the Dnipropetrovsk clan, and appointed then Donetsk boss Yukhym Zviahilsky in his place. When Kuchma was elected president the following year, he could not forgive Zviahilsky for his dismissal, and used the law-enforcement agencies to weaken the Donetsk bosses. In November 1994, Ukraine’s prosecutor-general launched a criminal case against Zviahilsky, who fled to Israel. According to Kuchma’s prosecutor-general, the murder of Akhat Bragin, the head of the Donetsk clan and president of the Shakhtar Donetsk footbalkl club until he was killed by a bomb in the directors’ box during a match in 1995, and of another oligarch-politician Yevgen Shcherban were ordered by Pavlo Lazarenko, one of the leaders of the Dnipropetrovsk clan and Ukraine’s prime minister in 1996-97, who was later convicted of money-laundering in the United States. Yanukovich and his friends also tried to implicate Lazarenko’s associate Tymoshenko in the killing of Shcherban.

In October 2010, former Ukrainian interior minister Yuri Lutsenko, who served in Tymoshenko’s cabinets, told a press conference in Lviv that ‘in recent years we succeeded in driving out these “thieves in law” from the territory of Ukraine, but now they are making a comeback and you see them actively participating in the political and economic processes of the state.’

An unscientific straw poll that I conducted in eastern Ukraine last week suggests that the vast majority of Russian-speaking, Kyiv-hating residents of the Donbas see themselves as Ukrainians. They have had enough of Yanukovich, Ivanyushchenko and their separatist stunts. They don’t want to merge with another country; they just want more power to run their own affairs and to spend their tax revenue – which is why ‘federalisation’ is another keyword for the Russian-speaker of eastern Ukraine.

The other keywords in the pro-Russian vocabulary at the moment are ‘referendum’ and ‘state language’, which Russian ceased to be as a direct result of the 2014 coup. A Crimea-style referendum on accession to Russia is just a tactic, but federalisation is a long-term objective and a very popular idea in eastern Ukraine where many people express anger at Kyiv’s tax-raising powers and spending priorities, which are imagined to favour the western half of the country.

Before returning to Kyiv, I spoke on the telephone with a senior figure close to Russia’s GRU intelligence service who said quite categorically that the Russia’s military and security ‘did not want Putin’s war’ and would go on not wanting it until he defeats Ukraine, which is unlikely, or there is a Kremlin coup. The GRU source went on: ‘Unfortunately, in Russia, decisions of war and peace are taken by Putin alone, and nobody can read his mind – which he may be losing anyway.’

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

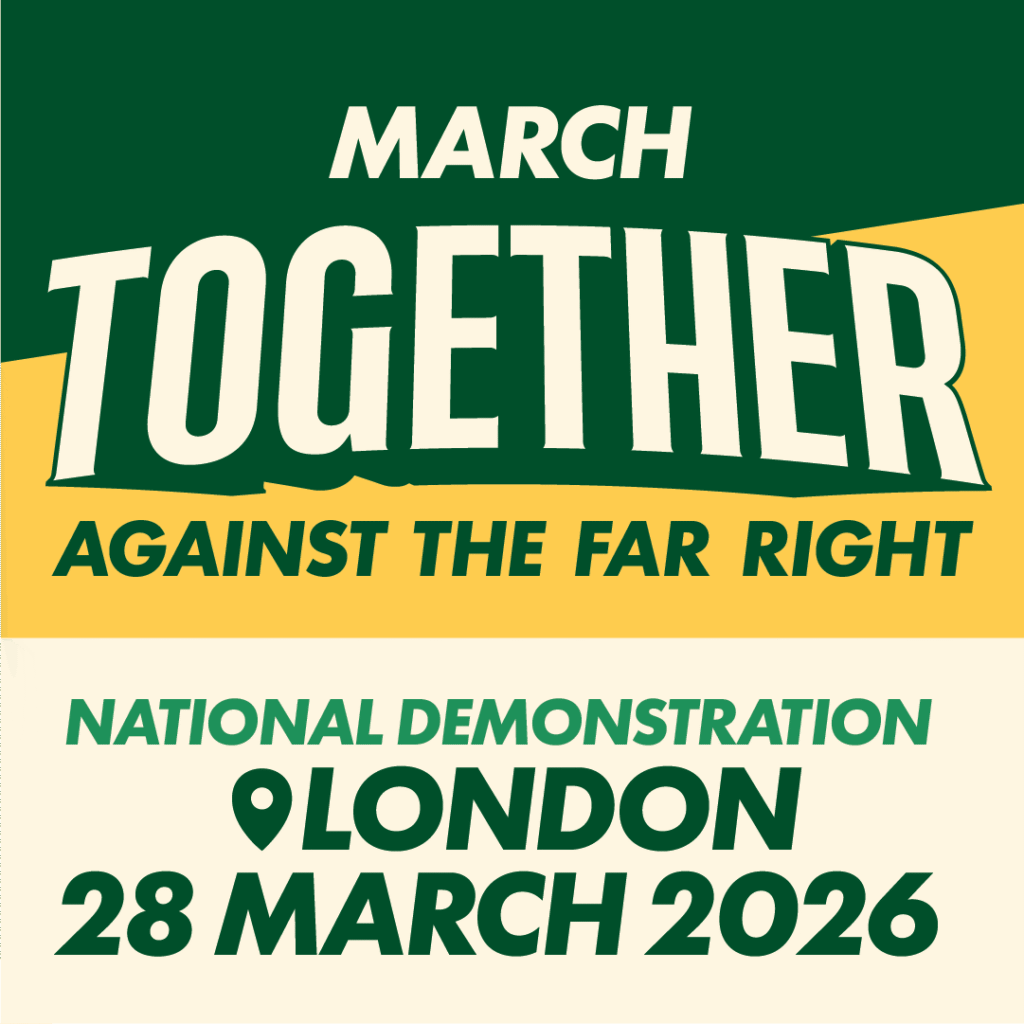

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.