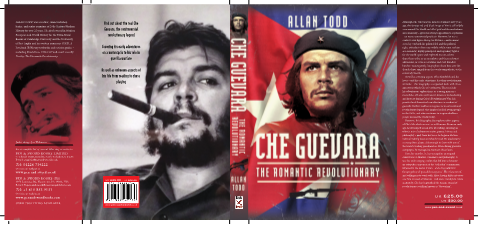

Che Guevara: icon of international revolution

This is an extract from the introduction of Allan Todd’s latest book Che Guevara, The Romantic Revolutionary.

‘Above all, always be able to feel deep within your being all the injustices committed against anyone, anywhere in the world. This is the most beautiful quality a revolutionary can have.’ [1]

Despite having been murdered in Bolivia almost sixty years ago, Che Guevara remains for many people – right across the world – the ultimate image of the romantic and idealistic revolutionary. Yet even for those who see Che as more of an idealistic romantic than a serious revolutionary, the above words may come as a surprise. For Che has been described by some as the archetypal exponent of implacable guerrilla warfare – or even as a cold-blooded Spartan-like warrior. Those words come from the last letter Che wrote to his children just before his departure for Bolivia in 1966, and was to be read to them in the event of his death. Yet such a belief had long been fundamental to Che’s humanistic Marxist politics – as reflected in another letter, written the year before: ‘At the risk of seeming ridiculous, let me say that the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love. It is impossible to think of an authentic revolutionary lacking this quality.’ [2]

Following his murder in October 1967, Che – described by Daniel Bensaïd as ‘the classic example of a man in a hurry’ – became a legendary revolutionary icon, and his romantic image came to symbolise all those who struggle against social and economic injustices, wherever they may exist. As Harris states: ‘Rarely in history has a single figure been so passionately and universally accepted as the personification of revolutionary idealism and practice.’ [3]

International Legend

Che’s international reputation began with his increasingly prominent role as a heroic guerrilla fighter in Fidel Castro’s Rebel Army that, in less than three years, ousted Batista – Cuba’s brutal dictator – in January 1959. He then rose to even greater prominence after 1959, when he took on various government and diplomatic roles in the Cuban Revolution. Along with Castro, he soon became the face of that revolution; and his growing international significance was such that, as early as 8 August 1960, he appeared on the front page of Time magazine in the US. Later, on 13 December 1964 – two days after strongly criticising, in a speech at the UN, the US government’s continued aggressions against Cuba – he was interviewed on the CBS News programme Face The Nation. As ever, he was wearing his green military uniform, and smoking a big Cuban cigar. [4]

World interest in him further increased when, in the spring of 1965, he suddenly disappeared from public view. Then, in April 1967, Castro read out Che’s Message to the Tricontinental. Written in 1966, before Che left for what would prove to be his fatal mission in Bolivia, it was said to have been sent from a guerrilla base ‘somewhere in the world’. Typically – given Che’s love of poetry – it began with a quotation from a poem by the nineteenth-century Cuban revolutionary, José Martí: ‘Now is the time of furnaces, and only light should be seen.’ When, just six months later, on 10 October 1967, the world learned of the circumstances of his murder in Bolivia, he became even more of a legend – with the famous red and black poster of him, based on Korda’s 1960 photograph, rapidly spreading around the world, and becoming a popular counter-cultural symbol of rebellion. [5]

One reason why Che’s murder resonated around the world was because, by 1967, he had emerged as a radical, undogmatic, independent and highly-principled freethinker, whose revolutionary

internationalist example and Marxist thoughts had begun to cross over from Cuba – his second homeland – into the politics of countries in Latin America and beyond. Che’s political beliefs – increasingly at odds with the restrictive socialism ‘actually existing’ in the Soviet bloc of the 1960s – were particularly refreshing for western Europe’s rebellious youth.

For the economist Meghnad Desai, Che ‘is a romantic figure. He is perhaps the best loved or at least the most paraded global icon that the Revolutionary left can claim. Even more than the bearded founders of the movement, Che Guevara caught the imagination of the 1968 generation.’ That ‘generation of ‘68’ was looking for a radical politics that was more libertarian, and was attracted by Che’s stated belief that: ‘The duty of every revolutionary is to make the revolution.’

Consequently, during the late 1960s and 1970s, Che’s image – on banners and T-shirts – was present on many demonstrations and protests. At the time, his murder was seen as a bitter blow by young would-be revolutionaries, with many viewing it as: ‘…the death of a revolutionary, a modern-day warrior chief. The left was in mourning: poets wrote elegies, laments that ended with calls to rebellion.’ Even historians critical of him – such as Farber – nonetheless recognise that, for many young people, Che was not just a key leader of one of the twentieth-century’s most important revolutions: he was someone who actually remained true to his coherently-expressed ideals and principles: ‘Even more appealing to many are Che’s personal values: political honesty, egalitarianism, radicalism, and willingness to sacrifice for a cause, including his position of power in Cuba.’ [6]

In Latin America itself, Che’s call – made in his Message to the Tricontinental, to create ‘two, three, many Vietnams’ – in order to weaken US imperialism’s ability to impose its political and economic interests militarily on underdeveloped countries – resulted in the formation of several guerrilla groups keen to overthrow their repressive and exploitative governments, and to weaken the global reach of the much-hated Yankee empire. For many in Latin America, his willingness to sacrifice his life spoke to a universal belief that the mark of an individual’s greatness is their preparedness to dedicate themselves to a cause that is greater than themselves. For Che, and for his would-be imitators, that cause was to end suffering, exploitation and oppression wherever it existed, based on the universal humanistic values of equality, justice and liberty. In many ways, his life – and death – enshrined those values.

Whilst news of Che’s murder undoubtedly pleased the CIA – whose file on him, first opened in 1954, eventually became its biggest on any individual – and the various dictators in Latin and Central America, a surprisingly-large number of the world’s leading thinkers, writers and artists rushed to pay tribute to him. Amongst the ‘great and good’ who did so were Alan Sillitoe, Christopher Logue, Frederic Raphael, John Berger, Italo Calvino, Andre Gorz and Graham Greene. Jean-Paul Sartre – one of Europe’s foremost philosophers in 1967 – had this to say on hearing of Che’s murder in Bolivia: ‘…I believe that [Che] was not only an intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age: as a fighter and as a man, as a theoretician who was able to further the cause of revolution by drawing his theories from his personal experience in battle.’ [7]

A Romantic ‘Renaissance Man’

Despite often being dismissed as merely ‘the romantic guerrilla fighter or the idealist dreamer,’ Sartre’s comment about Che being ‘a complete human being’ was surprisingly accurate. For many, though, his travels across Latin and Central America and his later involvement in guerrilla warfare seem to ‘have placed blinkers on history, blinding it to other aspects of this multifaceted man.’ In addition to his revolutionary activity – and the fact that he was a qualified doctor of medicine – Che was a prolific diarist and writer who left behind an impressive body of work. Even whilst conducting guerrilla warfare – whether in Cuba or, later, in the Congo and Bolivia – he continued to make notes and diary entries whenever the opportunity arose. He also maintained an extensive correspondence with family and friends. As well as his books on guerrilla warfare, he is also known as a bold traveller with a romantic sense of adventure, and a keen desire for new experience. His various travel diaries, written whilst in his early twenties, were published after his murder, and one formed the basis of the 2004 film, The Motor Cycle Diaries. [8]

From an early age, he was an avid reader of a wide range of poetry, fiction, and non-fiction – and soon proved able to quickly master new topics. In particular, he developed a real love for the adventure novels of Alexander Dumas and Jules Verne. His favourite novel seems to have been Cervantes’ Don Quixote, which he read at least six times. During Cuba’s guerrilla war, Che made that book part of the literary courses he gave to illiterate peasant recruits to the Rebel Army; and it was also the first book to be printed on a mass scale in Cuba within months of the Revolution’s victory in 1959. While, in the last letter he wrote to his parents, dated 1 April 1965 – as he was going off to fight in the Congo – he made a reference to that favourite novel: ‘Once again I feel beneath my heels the ribs of Rocinante. Once more, I’m on the road with my shield on my arm…’ [9]

Che loved poetry, and often quoted extensively from French poetry. He was particularly fond of the Chilean poet and communist, Pablo Neruda, the Cuban Nicolás Guillén, and the Turkish communist poet, Nâzim Hikmet. The latter has been described as a ‘romantic revolutionary’, whose political outlook was international and reached beyond borders – rather as Che’s internationalism was focused on opposing ‘Yankee imperialism’ across the globe.

Among the books Che took with him on his last mission were poetry volumes by Guillén and Neruda. Neruda had met Che in Havana, when Che was a minister, describing him as ‘dark, slow-speaking’ and whose ‘sentences were short and rounded off with a smile, as if leaving the discussion up in the air.’ Neruda had been flattered when Che told him ‘…that he often read my Canto general to the…guerrillas in the Sierra Maestra.’ On learning that Che – ‘the pensive man who in his heroic battles always had a place, next to his weapons, for poetry’ – had been murdered, Neruda wrote that: ‘Che Guevara’s official assassination, in poor Bolivia, was a bitter blow. The telegram announcing his death ran through the world like a cold shiver of reverence. Millions of elegies tried to join in tribute to his heroic and tragic life.’ Neruda saw Che as ‘a great guerrilla and a powerful political mind’ but very much ‘an exception.’ Though, as a more orthodox communist, Neruda didn’t support Che’s ideas about the usefulness of guerrilla warfare or ‘the romantic spirit and the wild guerrilla theories that swept Latin America’ in the years following Che’s ‘heroic death.’ [10]

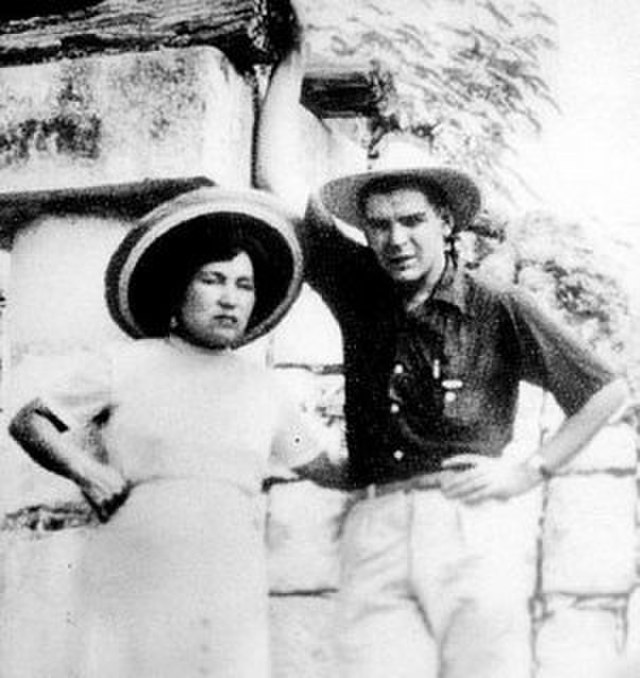

Che also had a deep interest in the ancient civilisations of Latin and Central America. As well as reading about them, he took every opportunity on his travels to visit Inca, Aztec and Maya archaeological sites – and spent much time in museums in order to learn more about an area’s ancient history. Even on his delayed honeymoon, with his heavily-pregnant first wife, he insisted on visiting Maya ruins:

As a result of all this reading and studying, he proved uncommonly erudite on a wide variety of subjects. He was also an exceptionally-good chess player – a game his father taught him at an early age, and which later became his main pastime. Che once achieved a draw in a simultaneous match given by the Polish-Argentinian International Grandmaster, Miguel Najdorf – who was amongst the world’s top chess players in the period 1939-49, and is best known for his Najdorf Variation of the Sicilian Defence. Finally, despite suffering badly from asthma from early childhood, he was very sporty, taking part in football, tennis, golf and especially rugby. His determination not to let his asthma limit what he did meant that, at times, he experienced serious attacks and sometimes had to be carried back home by his schoolmates.

==================================================

References

[1] Guevara, J. M., with Vincent, A., 2017, Che, My Brother, Cambridge, Polity Press, p.201. This letter is read out by Russell Brand on: www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bb6S9hraP3g (Accessed 08/05/22)

[2] Guevara, C.,1965, ‘Notes on Man and Socialism in Cuba’, in Hansen, J., (ed.), 1967, Che Guevara Speaks: Selected Speeches and Writings, New York, Pathfinder Press, p.136. Usually known as simply ‘Man and Socialism in Cuba’, it was written by Che in 1965, as he was on his way to help revolutionary fighters in the Congo.

[3] Besancenot, O. & Löwy, M., 2009, Che Guevara: His Revolutionary Legacy, p.111; Harris, R. L., 2007, Death of a Revolutionary: Che Guevara’s Last Mission, New York, Norton & Company, p.20

[4] Part of the interview can be seen on: www.youtube.com/watch?v=xELHGR_ur0Q (Accessed 08/05/22)

[5] The full text of Che’s Message can be seen at: www.marxists.org/archive/guevara/1967/04/16.htm

(Accessed 08/05/22)

[6] Yaffe, H., 2009, Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, p.viii; Stutje, J. W., 2009, Ernest Mandel: A Rebel’s Dream Deferred, London, Verso, p.163; Farber, S., 2016, The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice, Chicago, Haymarket Books, pp.xvi-xvii

[7] Alexandre, M., (ed.), 1968, Viva Che! London, Lorrimer Publishing, p.99

[8] Yaffe, H., 2009, Che Guevara: The Economics of Revolution, pp.1-2. A trailer for that film can be viewed on: www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_LAiSdIXos (Accessed 08/05/22)

[9] Zanelli, M., ed., 2017, Che Guevara: tu y TODOS, Milan, Skira, back cover

[10] Neruda, P., 1978, Memoirs, Harmondsworth, London, pp.299, 322-3, 330

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.