Fit for the future? The government’s ten year health plan

Greg Dropkin reviews the government’s latest approach to reforming the NHS:

Greg Dropkin reviews the government’s latest approach to reforming the NHS:

The Ten Year Health Plan pays lip service to the social determinants of health but then mainly turns away in favour of changing lifestyles and using technology and genomics to avoid hospitalisation. Local authorities, whose responsibilities include responses to some social determinants, are removed from the Integrated Care Boards in favour of Mayoral delegates to promote economic development.

Chapter 4 (From Sickness to Prevention) begins with Marmot on social determinants and conditions in Blackpool, the area with the lowest healthy life expectancy in England. It mentions the quality of jobs available and the standard of housing listed for rent. There are no proposals on job quality in Chapter 4, and the whole Plan gives no hint that safe staffing levels are essential in reducing stress and preventing ill health amongst NHS staff, or that union organisation is relevant to the “quality of jobs”.

Housing is mentioned in a sentence on other government initiatives: a) requiring social landlords [not others] to act promptly to fix housing hazards, b) a Warm Homes plan and Fuel Poverty Strategy. The word “homeless” occurs exactly once, in the Executive Summary: “Evidence shows that people in working class jobs, who are from ethnic minority backgrounds, who live in rural or coastal areas or deindustrialised inner cities, who have experienced domestic violence, or who are homeless, are more likely to experience worse NHS access, worse outcomes and to die younger.” That’s true. And?

How will the NHS be involved with the social determinants of health? The Plan sets out a prevention strategy based on 1) the NHS encouraging individuals to make healthy choices re food, alcohol, tobacco / vaping, weight loss, exercise; 2) government smoking bans, control of food advertising and sales to children of junk food, tobacco / vapes; 3) government programmes to improve public transport, reduce emissions and promote active travel, and the NHS working with Defra on measures to reduce air pollution through the Environmental Improvement Plan review; 4) vaccination, screening, early diagnosis; and 5) the NHS very enthusiastically using AI, genomics, new medicines, wearable devices to predict and monitor individual risk, involving partnership with high-tech industry.

Points 2) and 3) concern some important social determinants, but not job quality or housing, and only the work with Defra involves the NHS. Point 4) depends on health visitors and school nurses currently employed through local authority public health. Points 1) and 5) concern individual risk factors and screening / monitoring individuals with the latest technology.

How are these prevention strategies reflected in the Integrated Care Board structures? As Chapter 5 explains, ICBs will have delegates from the strategic authority mayors whose brief is economic development. Local government — whose work includes housing, environmental health, public health, and social care — will no longer have delegates on the ICBs.

Stop Smoking — or else!

The Plan states that “As set out in our elective reform plan, we will expect patients to engage with the support available to them, such as smoking cessation services. Evidence shows that stopping smoking 4 weeks before surgery means patients have a 25% lower risk of respiratory complications, compared to those who continue131”. The endnote cites a study which actually found something else: “Conclusions: Longer periods of smoking cessation appear to be more effective in reducing the incidence/risk of postoperative complications; there was no increased risk in postoperative complications from short term cessation. An optimal period of preoperative smoking cessation could not be identified from the available evidence.”

Immediately after misrepresenting this study, the Plan states “We have asked providers only to give patients a date for their routine (non-cancer) procedures once they have been confirmed clinically fit to proceed when pre-assessed”. Patients already go through a pre-assessment, but does this mean patients who have not stopped smoking 4 weeks earlier will now not be given a date for non-cancer surgery? No evaluation of the risks and benefits of any such policy is cited. How would it fit with a universal service, if patients are to be categorised as entitled or unentitled to NHS care according to their compliance with an offer of smoking cessation?

Secondary Prevention — vaccine uptake

The Plan recognises that there are problems with public trust. On immunisation, “We will continue to work with local government, civil society, voluntary organisations and community groups to support the public trust in vaccines needed to restore childhood immunisation rates more broadly.” Yet none of these organisations will be represented on the ICBs, apparently.

The Plan acknowledges variable uptake of secondary prevention (e.g. vaccines) and promises to “test new delivery models for secondary prevention through the Neighbourhood Health Service.” Will health visitors formerly employed in the NHS and then transferred to local authority public health be more effective if now employed in Neighbourhood Health Centres? The Plan offers no evidence.

The Plan proposes to use public and private finance for research into primary and secondary prevention, but makes no mention of conflicts of interest if research is funded by companies bidding for contracts.

Genomics — testing all babies at birth

Chapter 4 promises “a new genomics population health service, to harness the potential for predictive analytics to support more predictive and precise prevention in the future… Genomics and predictive analysis, supported by AI, can increasingly tell us the likelihood of a person developing a condition before it occurs, support early detection of disease (especially cancer), and enable personalised prevention and treatment.” And “[we will] create a new genomics population health service, accessible to all, by the end of the decade. We will implement universal newborn genomic testing”. The endless enthusiasm omits the issues raised recently in the BMJ by Trevor Sheldon and John Wright. They write:

…History is littered with examples of new technologies purporting to detect disease or the risk of future disease, and then being used to screen parts of the population, only to find later that the benefits were overstated, the associated harms under recognised, and the costs unjustified. That is why strict criteria were developed by Wilson and Jungner to be considered before introducing any screening programme. It is also why rigorous research is needed to inform such decisions.Crucial evidence will come from the Genomics England Generation Study, which aims to screen 100,000 newborn babies for over 200 genetic conditions between 2024 and 2027. However, we are some way off having sufficient evidence to assess the short and long term benefits and harms experienced by babies who are screened, as well as the cost-effectiveness and broader societal impact of such programmes. So, the recent announcement that newborn genome screening will be rolled out within a decade is premature and potentially undermines the UK’s rigorous screening governance arrangements…

It is the harms in particular that should concern us. Population genetic screening with its inherent false positives, false negatives, and unpredictable clinical consequences of mutations has the potential to generate a lifetime of anxiety for parents and their children. We run the risk of turning future generations into patients from the moment they are born, with overdiagnosis and overtreatment, as well as profound implications for how these data will be used by third parties such as life insurance companies.

More worrying though is the obsessive focus on technology where there are important modifiable social determinants or risk factors which newborns are exposed to at individual and a community level…

Preventative medicines

Other high-tech prevention strategies appear elsewhere in the Plan. Preventative medicines will be rolled out quickly.

From personalised treatments to preventative medicines with huge population relevance (e.g. GLP-1 agonists), the pace of future discovery is even more exciting. Beyond their impact on health, many promise substantial societal and economic benefit, including by helping more people stay in productive work. We want to make sure the NHS patients have fast access to these medications…In collaboration with partners across the public, private, and charitable sectors, we will support development and roll out of high impact medicines including in cancer, obesity and dementia. We intend to set up public-private partnerships to accelerate development and implementation of new dementia therapies. We will also be more proactive in preparing the system to implement medicines in areas like asthma, where new care models can shift care into the community.

Monitors and sensors

In the heroic Chapter 8 on technology, the Plan discusses wearable monitors and biosensors.

New wearable technologies mean that we can measure and monitor our health and health behaviours like never before – from apps on our phones, to smart rings on our fingers, to continuous glucose monitors under our skin.As of early 2024, around two-thirds of people surveyed reported tracking at least one aspect of their health using an app or a device. Smartwatches are set to reach 10 million people this year.This trend will accelerate. We will see miniature, highly accurate biosensors continuously monitor a wide array of physiological parameters. Smart fabrics and nanotechnology will enhance sensor capabilities. AI algorithms embedded in wearables will analyse data to detect early disease, predict adverse events and provide personalised coaching.

The virtual wards programme, scaled-up during the pandemic, [allows] patients to stay at home while they are remotely monitored by their care team. When people need help, teams respond proactively. In the first 3 years of this Plan, we will expand hospital at home programmes and expand National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE) digital programme to consider more medical-grade wearables.

We will connect wearable devices and biosensors to the NHS App, empowering people with access to their own health information in real-time. We will bring it together in one place, so it can be easily shared with neighbourhood teams. Over time, citizens will be able to integrate their data from smartwatches and other devices, with their Single Patient Record. This will open up new opportunities for better care, as well as for research.

The issues raised by Sheldon and Wright in relation to universal genomic screening are also relevant here: overdiagnosis, overtreatment, data use by third parties such as life insurance companies. “More worrying though is the obsessive focus on technology where there are important modifiable social determinants or risk factors…”

Having begun Chapter 4 with Marmot and a description of social reality in Blackpool, the Plan pivots the NHS away from the social determinants of health and into the seductive embrace of technology. No surprise, given the Health Secretary’s former role as a Vice-Chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group on the 4th Industrial Revolution.

This article was first published on Labournet

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

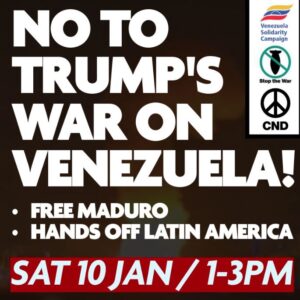

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.