The Dilemma between Post-Democracy and Pre-Fascism

Donald Trump, a relentless right-wing populist, outed as a sexist defender of rape culture, becoming the 45th president of the US proves that the rise of right radicalism is not confined to a number of states and regions and is not just a European issue but rather is the expression of a global political crisis.

How can this be explained?

This is not about overtly neo-Nazi parties at the margins of the political system but about parties attaining 20, 30 and more percent in national elections through their ability to tailor themselves to the contemporary political and cultural mainstream.

The first over-simplification concerns the social composition of the constituencies of the far right.

A lot of empirical material has been compiled to demonstrate that the rise of the radical right parties in Europe and elsewhere is the expression of demoralized and confused lower classes which is contaminating society.

There is much evidence of the inroads of right-wing radical parties into proletarian, formerly social democratic electorates. However, the data in most cases ignore the vote shares in other segments of the electorate and are therefore prejudiced and ideologically biased.

Anyway the political component must not be ignored.

In Europe, according to ‘Eurobarometer’ data, people feel increasingly uncomfortable about their democracies. According to a survey last year, 62% of Europeans believe that things are going in the wrong direction, 48% declare that they don’t trust their governments anymore and 43% say that they are unsatisfied with their democracies.

The causes of this are complex. Alongside crisis, precariousness and the middle strata’s fear of downward social mobility, there is the decline of social democratic parties. Disillusionment over this, when the left doesn’t present a credible radical alternative, ends all to easily in delivering people up to the radical right.

Unfortunately few attempts are made to answer the simple question: Why does the crisis, which large numbers across society understand to be a ‘crisis of the system’ – whatever people understand the system to be – spur the radical right to a much greater extent than the radical Left?

Antonio Gramsci, writing from an Italian fascist prison between 1929 and 1935 warned the Left about this. ‘It may be ruled out’, he wrote in the Prison Notebooks, ‘that immediate economic crises of themselves produce fundamental historic events; they can simply create a terrain more favourable to the dissemination of certain modes of thought’.

The answer to this dilemma cannot be found in empirical data. It requires critical theory.

I start with Cas Mudd’s definition of the ideological core of populist right radicalism; he speaks of a combination of three elements:

-

- Authoritarianism

- Nativism, understood as ethnic nationalism (xenophobia, racism, and anti-Europeanism) connected with a strong social chauvinism limiting social benefits to native citizens only.

- And ‘populism’ which addresses the anti-establishment feeling of large layers of the society by invoking an unbridgeable divide between a corrupted elite and a pure, morally homogenous people – as Canovan and Laclau have also described in their writings.

It would be interesting to know to what extent the analysis by contemporaries of the rise of fascism in the 1920s resembles what today’s political scientists call ‘right-wing populism’.

Gramsci characterized fascism as the reaction to a crisis of the state, consisting in the unsettling of existing certainties that functioned to hold together the state, that is, the dissolution of the hegemony of specific concepts and ideologies: ‘The great masses have become detached from their traditional ideologies’, he notes, (…) ‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’

Interestingly the Hungarian-Austrian socialist, Karl Polanyi concludes alike: ‘Fascism, like socialism, was rooted in a market society, that refused to function’, meaning the ‘collapse of the “utopian endeavour” of constructing societies and international relations on the basis of a “self-regulating market system”’.

These observations from almost a century ago are relevant for understanding how a structural crisis of capitalism produces different kinds of hegemonic scenarios; for example why the 1970s crisis triggered neo-liberalism, which in the UK and US advanced through a populist push, while the financial crisis 2007/2008 spurred populist right radicalism.

In contrast to the thesis that the populist radical right in western democracies were ‘a pathological abnormalcy’ which of course would be politically uncomfortable, Cas Mudd denotes it as the expression of a ‘pathological normalcy’ i.e. the particular ideological and cultural climate created by neo-liberalism itself.

The thesis of the ‘pathological normalcy’ in neoliberal capitalism helps also in understanding the sudden change in public opinion last year in Germany and Austria which after the short ‘summer of solidarity’ polarized and turned hostile against the refugees. Mudd demonstrates by reference to Euro-Barometer that this was not actually so sudden. Already in 1997 only one of three of those interviewed in the then EU-15 felt they were ‘not at all racist’, another third declared themselves as being ‘a little racist’, while another third expressed quite openly racist feelings. Even then going beyond most radical right populist parties, 20% supported ‘wholesale repatriation’ agreeing with the statement that ‘all immigrants, whether legal or illegal, from outside the European Union and their children, even those born here, should be sent back to their country of origin.’

So rather than being completely outside of the neoliberal mainstream the populist radical right constitutes ideologically and attitudinally a radicalisation of its values.

Moreover this radicalisation should not be regarded as the spontaneous reflection of the crisis. On the contrary it has been incited and promoted by corporate media outlets and the cultural industry. It is also notable that the ruling ideas of each age have always been the ideas of its ruling class which reacts to a changing situation by all means available to it.

A short remark on nationalism: A rise of nationalism always is the index of the deterioration in national relations. In the European case this is due to the growing inequality between the centre and periphery, accompanied by a reinvigorated rivalry between the major powers, Germany, France and the UK. Both of these developments are the result of neoliberal austerity and its unequal consequences.

Here it is crucial to understand that the EU is not just an economic and currency union but a system of institutionalized political relations between states and nations.

And paradoxically, as much as Europe’s radical right are divided through competing nationalisms they converge politically in their strong anti-Europeanism.

Consequently without ending austerity nationalism cannot be forced back.

Even after the US election the fight with the populist radical right is not lost. However the radical Left has to deal with four political challenges:

- We must shift the emphasis in confronting right radical populism from moral condemnation to political struggle. That requires firstly acknowledging the validity of the social concerns, complaints and criticisms which people face. The decisive battle ground with the far Right is the overcoming of mass unemployment and youth unemployment, as well as discrimination against women. We must not only raise these issues but propose feasible strategies for a socio-economic transformation towards a common solidarity economy, in other words a rupture with the system on both the national and the European level.

- The claim of the populist right to be an ‘anti-systemic’ force is wrong. In aiming at replacing liberal democracy, human rights, women’s liberation and the rule of law with an authoritarian ‘Führer-state’, their function is to stop a system change from happening. But this means that if the Left confronts the populism of the radical right it has at the same time to defend democracy against its distortion and depletion by neoliberal governance. Democracy cannot be defended in alliance with the ruling forces but in opposition to them.

- Defending democracy on the national level is not identical with nationalism. While defending the former the Left must not compromise with the latter. Choosing between democratising the nation-state and strengthening transnational democracy would mean accepting a false dilemma. On the contrary, the Left must design a programme of integration which would set up a democracy on the European level while respecting democratic self-determination of its national components.

- Europe’s culture is poisoned by Eurocentrism. The very idea of ‘white’s man superiority’ – going back to the Enlightenment and entrenched through the colonialisms of the European powers up to the present day – shapes, notwithstanding its metamorphoses, the prejudices of Europeans and US-Americans, preventing their societies from adjusting to the great transformation the world is undergoing. However, without changing the prejudices and mindsets of the working classes in the capitalist heartlands, democratic and cultural progress will not be possible nor will it be possible to prevent the looming regression into barbarism which is the aim of far-right parties.

This article was first published on the Transform website

1 comment

One response to “The Dilemma between Post-Democracy and Pre-Fascism”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

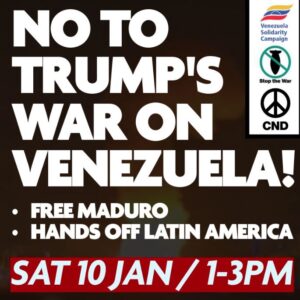

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

This is the most vital decision facing the contemporary Left – how it confronts the onward march of the radical right. The first wave of the radical right after World War One sought to displace the old imperial and liberal regimes that had been humbled and rendered weak by war and internal rebellion. In the German case, Strasserism, with its working class base, prefigured what the radical right is achieving this time round, yet not a single book has been written on Strasserism. Democracy has never been a strong suit of the Left – Leninist-Trotskyists dispensed with or ignored it and Social Democrats just went along with the same bourgeois democracy that has degenerated and lost its legitimacy. We start therefor from a position not just of electoral but of political weakness and this must be rectified.