Report: White Flowers campaign meeting

Terry Conway reports on the campaign meeting against establishment child sexual abuse.

More than 400 people packed into Committee Room 14 in the House of Commons on Wednesday 14 January for a public meeting organised by the White Flowers Campaign, with many standing or sitting on tables and the floor to crowd in.

With an extensive platform – the majority survivors of child abuse but also whistleblowers, child protection professionals, campaigners and MPs – the meeting sent a united and powerful message, not only to those present, but to the establishment that the voices and demands of survivors need to be put at the centre of the Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse.

The White Flowers campaign, as long standing whistleblower Liz Davies explained, takes its name and a great deal of inspiration from the Belgian campaign, after 275,000 marched in Brussels in 1996 after the cover-up of the kidnapping, rape and other torture and murders of children and young women by a powerful paedophile ring in that country, carrying white flowers and white balloons.

The campaign in Britain organised two vigils in 2014, firstly on the site of the former Elm Guest House in Barnes where organised sexual abuse is alleged to have taken place in the 1970s and 1980s involving an organised network of abusers including MPs and others in positions of power, and then at the former Islington children’s home in Grosvenor Avenue. Former Deputy Superintendent of Grosvenor Avenue, Nicholas John Rabat, was charged in Thailand in 2006 with abusing 30 local boys – the youngest six – and killed himself.

Both events, especially the second that received more publicity, resulted in more survivors and whistleblowers being given confidence to speak out. There are plans to hold more local vigils at sites where abuse happened – unfortunately there are all too many sites to choose from.

Towards the end of last year however, focus shifted onto national political questions. In July 2014 home secretary Theresa May was forced to set up an inquiry into child sex abuse following pressure from campaigners. However initially she thought she and the rest of the establishment could severely curtail its impact through appointing a chair who she felt comfortable with – and by drastically limiting its terms of reference.

Baroness Butler Sloss did not last long as chair of the inquiry, resigning after only a week after allegations that her late brother Michael Havers was involved in a major cover up of child sexual abuse became more widely known.

Fiona Woolf, appointed on September 5, lasted rather longer – hanging on until the end of October. But in the end the disclosures about her relationship with Leon Brittan, who was also implicated in serious allegations of cover up, became too widely known and she also resigned. Earlier that day survivors met the inquiry panel’s secretariat for the first time and made very public their call for her to step down.

But if the question of chair of the chair of the inquiry has rightly received publicity, there are some dangers in this approach. The media have tended to use the formula that what is being demanded is an independent chair. But an equally pertinent question is: independent from what?

Campaigners want a chair who is independent from those against whom there are accusations of wrongdoing – including covering up of abuse, which itself is a very serious attack on survivors because it protects perpetrators. But we don’t want someone who is neutral in the sense of being unconcerned with the demands of survivors. We need to turn the tide in the context that thousands of survivors have gone through the ordeal not only of the abuse they suffered but of then having their disclosure disbelieved, trivialised and covered up.

There are far too many stories, for example, of people being threatened with – and subject to – proceedings under the Mental Health Act for coming forward with allegations against abusers. There are far too many testimonies of young people being punished, moved away from a peer group that could give them support, isolated or just ignored. This has also happened to many who have only felt able to disclose what happened in adulthood.

The campaign has asked supporters to canvass support from their MPs for the following demands:

• A statutory inquiry to cover organised and institutional child abuse post 1945

• Hold members of the establishment to account

• A parallel national police investigation team delivering justice

• Scrap the inquiry panel & re-appoint on a transparent and fit for purpose basis

• Appoint a chair who has demonstrably stood up to the establishment

• Defend child protection services

• A government funded National Institute for People Abused in Childhood

They themselves, working with other survivors groups and individuals, have ratcheted up the pressure on May since Woolf’s resignation so much so that when she gave evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee on December 15 she stated, in response to a question from Keith Vaz MP, that “The message I am very clearly getting is that this is an inquiry that should have the powers to compel people to give evidence and to enforce.” She continued that this could happen either at the request of a new chair or through the setting up of a new inquiry panel with statutory terms.

It’s the drive of the White Flowers campaigners, working with others, that has got us this far; from around a dozen of us in Barnes to more than four hundred in the House of Commons, from a situation where May’s decisions were yet another slap in the face for survivors and whistleblowers to one in which she is forced to take seriously what those groups are demanding.

Speaker after speaker at the House of Commons meeting explained through personal testimony why the growing dynamic of unity amongst survivors and the achieving of their demands were so important.

Andy Kershaw from Survivors of Forde Park, an approved school for boys in South Devon where four people were eventually convicted of abuse – but almost 200 more about whom survivors complained were never even investigated – explained that the current terms of reference of the inquiry which are set at 1970 would preclude these cases being taken up again.

Nigel O’Mara movingly explained the lifelong effects his own experience of childhood sexual abuse had had on him and argued strongly that there needed to be really effective support services for survivors. Sarah Champion, Labour MP for Rotherham, who explained that she had not slept for days after reading the report into what had happened there, argued that cuts and privatisation would make real support even less attainable.

Phil Frampton in opening the meeting told of the resistance that built up amongst the young people who were being systematically abused in the home in which he lived. Some of them initially tried to resist by confronting the superintendent physically. In the end, after years of being disbelieved and ignored, a whole group of young people refused very publicly to get off a bus until the police came and took away the perpetrator. Unity is strength.

Definitions were explored – and contested – amongst contributors. There seemed to be consensus that all abuse, be it physical, emotional or sexual or a combination of more than one form, needed to be taken seriously. Though there was not time for this discussion, many would argue that they all come from the same abuse of power by the perpetrators. Someone argued that by talking about abuse rather than rape, torture and murder there was a danger of playing down the crimes that had been committed.

There were many common themes amongst the disparate contributors – and it is impossible to do them all justice in this piece or give more than just a small flavour of the event. Disappearing files is a recurring pattern in experiences up and down Britain, in individual places where children have been abused, in social services offices, in solicitors officers (not only those that were collated by Jeffrey Dickens MP) and it is not credible to think that this is some gruesome coincidence.

Several speakers talked about the role of insurance companies in perpetuating cover ups. Tim Hupbert the former director of Bedfordshire social services for example explained that he was told that he was told not to apologise for anything that had happened on his watch – because to do so was to admit liability and this would cost the authority money. So greed denies justice for survivors – who are often grotesquely portrayed as being money-grabbing, as if anything could compensate for what many have endured.

Paul Gosling, who wrote Abuse of Trust: Frank Beck and the Leicestershire Children’s Homes Scandal jointly with Mark D’Arcy, also mentioned the fact that the insurance companies there had been to argue against any admission of liability. But probably his most telling point was that many of the names that became familiar to him through the work on Leicestershire also come up in other authorities – one of the most compelling reasons why all this work needs to come together in order to get justice for survivors and to make children and young people today and in the future safer.

John Mann MP said that in every single children’s home in Nottinghamshire people had come forward to disclose abuse. There was a strong sense that what most of us know about is only the tip of the iceberg.

One of the most powerful contributions came from Stuart Syvret, former Jersey senator and minister for health and social services there, who has been campaigning over issues of child abuse on the island since 2007. Haut de la Garenne, the former children’s home on the island, is rightly one of the most notorious names in the tragic chronicle of organised child abuse. And as time has gone on the links between this site and places where organised abuse has taken place in Britain have become clearer – for example we know that children from Islington where taken to Jersey.

But Stuart’s contention was and is that the abuse was much wider than most people recognised. His blog argues:

“What we are dealing with isn’t just Haut de la Garenne – the abuse and torture of vulnerable children didn’t end at that place. Child abuse was prevalent at many other Jersey run institutions. Both during the same era as Haut de la Garenne and most definitely after that place was closed in 1986.

What we are dealing with is a continuum of abuse;

A culture of comtempt

A culture of disregard

A culture of abuse

A culture of concealment

And it didn’t end with Haut de la Garenne

It continues to this day.”

On the basis of his campaigning (although this has often not been the basis of public argument) he has served two terms of imprisonment of three months and is likely to be declared bankrupt very soon.

Stuart, like everyone who spoke – and many of those who did not – has been working for years around these issues. Many have shown enormous courage in persisting to raise these issues despite threats and real personal detriment. Between them they have a wealth of experience which could be put to use if there was a real commitment to dealing with organised child abuse and the cover ups that it has been met with.

As Liz Davies argued, for a long time people have been whispering in dark corners but today we are shouting out loud. There will be no going back.

Left Unity has supported the White Flowers campaign from the beginning and will proudly continue to do so. The campaign is now looking to organise a series of regional meetings to extend the discussion on the issues beyond the audience that were able to come to the House of Commons on January 14 and we will make sure news of these are got out to branches as they are organised.

One way in which we want to step up our work against child abuse is to talk the issue more systematically into the trade unions. Comrades in the NUT from two associations have been centrally involved in putting motions on the question of child protection, which have been composited into a motion that will hopefully be discussed at Conference at Easter. It would be very helpful if other comrades could argue for this motion to be prioritised.

One absolutely essential part of that motion is its argument that those whistleblowers who have been forced to sign compromise agreements in which they give away their right to disclose what happened should have these overturned without losing any financial settlement. Many trade unionists are aware that such confidentiality agreements are often distinctly dubious, so this could be a way of opening up a broader debate on this issue – but it is anyway worth fighting for in and of itself. Those who have fought to have the abuse of children taken seriously should be championed by the trade union movement, not as has so often been the case driven out of employment often with their professional reputation wrongly tarnished.

It would also be excellent if other comrades in Left Unity could consider putting similar motions to their own union conferences.

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

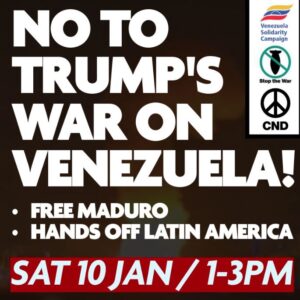

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.