How to start a foodbank: the story of Luton Foodbank

As the Daily Mail attacks foodbanks, Mark Boothroyd of Southwark Left Unity looks at how they are really run – and calls for the left to rediscover its traditions of mutual aid

What place does food hold in the constellation of human needs? Maslow’s hierarchy of human need puts food among the base of human needs, alongside breathing, water, sex, homeostasis, sleep and excretion. It should be clear to all that food is a basic need, which is central to a cohesive, stable, humane society. Bertolt Brecht wrote in The Threepenny Opera, “First comes feeding, then comes morality.” If you cannot obtain food to feed yourself, then all other questions of culture, morality, law and right become secondary or meaningless.

What then will be the social impact of the government’s widespread and growing starvation of hundreds of thousands of its citizens? The impact of the brutal and draconian welfare reforms that rob tens of thousands of their only means of subsistence is driving as many as 500,000 people to access foodbanks across the country. The Trussell Trust, a Christian foodbank with some links to the Labour and Tory parties, has doubled the number of foodbanks it supports in just one year. The Trussell Trust had predicted demand of 200,000 for 2012-13. The latest reports say they have distributed almost a million food parcels in 2013-14. As the Trussell Trust only manages 37% of foodbanks in Britain, the total number of food parcels distributed will be much higher. The Mirror reported that 45 foodbanks distributed 182,000 food parcels between them.

A significant portion of the population are being prevented from obtaining a subsistence level of existence. The pain and misery this causes is impossible to quantify. Its social impact is being told in stories of expanded free school meal programmes, parents going hungry, desperate robberies, rising malnutrition and a hundred thousand small tragedies as people try to maintain a minimum existence with next to nothing.

Into this gap viciously vacated by the state are stepping the foodbanks. The Trussell Trust is an establishment response, it provides a franchise which can be rolled out through religious institutions, organising foodbanks through churches around a Christian ethos of helping the poor and vulnerable. The trust itself provides a section of the elite with jobs and salaries from the charity of others while it provides a minimum to ameliorate the worst aspects of the government reforms.

There are ways of creating a foodbank independently of its network. Organisations like Luton Foodbank show how foodbanks could be built by those actively involved in stopping the reforms, who see the necessity of providing for those affected by them in the here and now.

Luton Foodbank was originally the initiative of members of Luton Council’s Social Justice department. Tasked with analysing the impact of the government’s welfare reforms, they quickly ascertained the scope of the devastation the reforms would wreak on the working class and poor in Luton. Spurred on by this knowledge, six activist members of the department began to discuss what they could do in response.

Settling on the idea of creating a foodbank, they organised an open meeting and advertised it through churches, unions and community groups. Over 80 people attended the initial meeting, including local Labour and Tory party members, trade unionists, community activists and local citizens. While some wanted to set up a foodbank linked to the Trussell Trust, it was thought this was not practical in such a diverse town as Luton. Muslim residents were unlikely to seek help from a Christian charity organising through the churches, just as Christians would be unlikely to go to a mosque, so it was decided to form a non-denominational foodbank and organise distribution points through community centres.

The initial meeting set up a Development Group, which was in charge of the overall direction of the project, and five working groups, each concerned with a different technical aspect of setting up the foodbank. They drafted a business plan and set to work.

The working groups were:

- Referral agencies

- Volunteers and training

- Warehouse, van, administration

- Donations, sponsorship and fundraising

- Public relations, marketing and communications

The working groups sent reports back to a monthly Development Group meeting as progress was made in their relevant area.

To learn how to set up the foodbank, members of the development group visited Milton Keynes foodbank, which had been established eight years ago and is now strongly rooted in the local community. Milton Keynes provided them with advice and information, and a number of practical resources like the foodbank stock spreadsheet which maintains an accurate account of food left in the warehouse with minimum effort. The spreadsheet was developed by a Milton Keynes foodbank volunteer, but is usable by any organisation working to set up a foodbank.

Community and Benefit Society

It was decided to set up the foodbank on a cooperative model. The Development Group received advice from Co-operatives UK on what legal form the foodbank should take, and they and set it up as a Community and Benefit Society. This is a form of non-profit organisation with community and social objectives, run and managed by its members. Community and Benefit Societies are registered with the Financial Conduct Authority under the Industrial & Provident Societies Act.

Objectives of the Luton Foodbank (BenCom) from the Foodbanks business plan:

The objects of the Society shall be to carry on any business for the benefit of the community of Luton by:

- 1) Provision of nutritionally balanced and culturally appropriate food free to people in hardship or distress who are referred to the foodbank by a network of agreed referrers.

- 2) Promoting healthy eating and supporting local opportunities for food growing and the expansion of foodbank activity through the development of a community food purchasing scheme.

- 3) Providing signposting information to local advice and information services.

- 4) Promoting co-operative working and social cohesion.

- 5) Promoting the principles of fair trade

These are incorporated in the the Foodbank’s principles:

The Luton Foodbank will be run entirely for the benefit of people in and around Luton who need emergency food aid

The Luton Foodbank will not be aligned to any faith group and will be non-judgemental

The Foodbank will provide short-term emergency food packs to help people in immediate need, but will also aim to help people resolve the problem which led to the visit.

The foodbank was extremely lucky in that they received a donation of £50,000 from Luton Airport to fund the organisation. As Luton Airport is owned by Luton Council while management of the airport is outsourced to a private company, part of its operating profit must be distributed to charities and other non-profit organisations. The foodbank applied and received a grant to help with their work. While this beneficial situation won’t be faced by many foodbanks, it doesn’t invalidate the lessons that can be learnt from Luton Foodbank’s creation and operation.

Referrals

The referral agencies working group was tasked with finding services and organisations which were suitable to operate as referral points for people vulnerable to food poverty. The referral agencies direct those in food poverty to the foodbank, and provide vouchers to access its services.

Initially there were just three referral agencies, but as the project grew more organisations came on board they now accept referrals from some 40 organisations across Luton. Agencies they accept referrals from include Citizens Advice Bureau, women’s shelters, older people’s charities, mental health charities, children’s centres, schools, colleges and parts of social services. Referral agencies sign a Memorandum of Understanding with the foodbank to establish their mutual responsibilities and the limits of their relationship. A handbook was produced by the foodbank to act as a guide for those making referrals so they use the service appropriately.

When a referral is made the agency ask the person to fill in a referral voucher to help the foodbank identify the reason they are having to access the service. It allows the foodbank to identify which part of the community the person is from, and what are the causes of them falling into food poverty. This is so they can be directed to the appropriate service to access the help they need to address the problems forcing them into food poverty; be it benefit sanction, low pay, homelessness, domestic abuse or the myriad other issues which drive people into food poverty. Referral agencies can issue people five food vouchers in a 12-month period. This may seem meagre, but there is flexibility granted depending on users circumstances. When I visited, one person had been receiving food from the foodbank for three months while they appealed against a six-month benefit sanction. The five-voucher limit serves as a guideline limit to prevent abuse and to encourage people to access services to help them resolve the issues which are forcing them into food poverty. The foodbank does continue to provide food to those whose difficulties cannot be resolved within a short time frame.

Volunteers

Volunteers and training were concerned with finding people who would work with the foodbank in the various roles it required. The include manning distribution and collections points, van driving, administration and sorting and packing food parcels at the warehouse. This is not a simple tasks as volunteers running distribution points need to have a Criminal Record Bureau check as they are working with vulnerable adults in this role. Initially the foodbank recruited volunteers through the council’s volunteering website but this was a long and time consuming process. They now advertise for volunteers when doing collections and through their website, and the foodbank runs a welcome workshop every three weeks which potential volunteers can attend. They are shown round the warehouse and interviewed to assess what skills they can bring to the organisation. For instance, volunteers with IT or graphic design skills have been asked to contribute work on the foodbank’s website and admin systems rather than spend their time filling food parcels. Those who wish to volunteer at distribution points can apply for their CRB check, but as this is costly and time-consuming, a small pool of volunteers who already have CRB checks staff the distribution points.

Young people are invited to help with data entry and updating the foodbank records so they have accurate information as to how much has been collected, donated and who it has gone too. The foodbank has sought to welcome all parts of the community to participate in it.

The foodbank has volunteer sessions on Tuesday and Thursday to sort donations and pack food parcels, and usually has two to three volunteers to staff each of the five distribution points throughout Luton.

Volunteers from various services also attend the distribution centres to provide advice and contact the service users directly. These can be volunteers from Citizens Advice Bureau, mental health charities and advocacy organisations. They perform outreach work via the foodbank to find people in need of their services, working to identify those most in need and initiate interventions as soon as possible to try and resolve the crisis affecting that persons life.

Warehouse

Warehouse, Van and Administration was concerned with the logistical side of the foodbank; securing warehouse space to store the food and a vehicle to carry food from collection points to the warehouse, and to the aid points at community centres. They appealed for a vehicle to be donated by local businesses but none were given, so they agreed to spend some of the money from Luton Airport on purchasing a van.

The warehouse space they use is owned by Luton Council, with a slightly reduced charity rent. The warehouse is organised by a volunteer with years of experience working in warehousing. The main obstacle to setting up the warehouse was finding enough shelving and racking to store all the food on. Various pieces were donated by shops and businesses being refitted, and a business that vacated the retail park donated their racks to the foodbank, but it was a struggle initially to create enough storage space for the 3,000+ food items stored in the warehouse.

Food is stored and organised by expiry date. If it expires in 2014 it is separated by month and those items closest to expiry are used first; expiry dates further away are organised by year. All the goods collected are non-perishable, tins or cartons.

Donations

Donations, sponsorship and fundraising was concerned with organising food collections and attempting to make the foodbank sustainable through sponsorship from local businesses and fundraising from residents.

Roughly 70% of the foodbanks supplies are collected from schools. As a member of the development group was a teacher, they used their links to quickly establish relationships with schools across Luton. At two schools a month they organise an assembly where foodbank volunteers run an interactive session with the students discussing the reality of food poverty in Britain. The schools will hold a non-uniform day, and a letter is sent to all parents informing them that this is in aid of the foodbank, and instructing them to give their child a food item to donate, instead of the customary £1. With most schools having upwards of 1,000 pupils, this ensures a mass of donations to the foodbank regularly, and creates opportunity to speak with young people about the reality of poverty in Britain.

Tours of the foodbank are also organised by schools, and the pupils spend an hour or two sorting food and packing food parcels in the warehouse.

The rest of the food comes from collections at supermarkets and shopping centres, donations from individuals and businesses and food drives by churches and mosques. The collections are planned well in advance to ensure a steady supply of food, and to allow publicity to be circulated to volunteers and those wishing to make donations. They also organise around religious festivals like Eid, Ramadan and Christmas. See their events calendar for this year.

There are also recognised drop off points where citizens can make donations to the foodbank. Volunteers then drive round and collect the donations once a week.

PR, Marketing and communication

This working group communicates with the various agencies, faith groups, schools, businesses and the council and produces publicity materials for the foodbank, such as their brochures and their referral forms.

They write letters to local businesses asking for support for the foodbank, and contact churches and mosques to encourage them to support the foodbank and organise their own collections.

They maintain the foodbank website as a source of information and news about the foodbank, with links to donation points, list of food items to donate, ways to become a volunteer and actively support the foodbank or make financial donations.

Starting the foodbank

Although initially run by volunteers, the foodbank benefited from a large grant of £50,000 from the Luton Airport Community Trust Fund. The airport is owned by the council but managed by a private company. As part of its community relations strategy it runs the Community Trust Fund to support organisations which benefit the local community. The foodbank applied for a grant to start the project.

This money was used to purchase a van for collections and distribution, pay for the initial warehouse lease and to employ a coordinator for the foodbank. While initially run by volunteers, and still heavily supported by them, the day to day operation of the foodbank is now managed by the coordinator. The job description is available here. They are working to secure regular donations to meet the running costs of the foodbank. If they can secure enough regular donations then they will be largely self-sufficient and able to operate independently of grants or other support.

The foodbank opened in April 2013 with a soft launch in order to not be overrun with demand. Their referrals grew from 20 to 200 in the space of a month, indicating the scale of the social crisis afflicting the poor, unemployed and vulnerable.

Distribution

Initially the foodbank had just two distribution points in the town. They have now expanded to five distribution points, one for each day of the working week. As Luton Foodbank is a non-denominational organisation the distribution points are all based in community halls and centres and other community organisations. This makes them easily accessible to all the different communities, the property of all rather than just of one religious or ethnic group.

Approved volunteers staff the distribution points, taking people’s referral vouchers, checking them against the records submitted by the referral agencies and keeping account of what is distributed.

During my visit a wide spectrum of Luton’s citizenry cross the door. A young woman with learning difficulties who had been sanctioned. A young man who had just lost his job, waiting to sign on and receive benefits. A teenage migrant struggling to make ends meet on his poorly paid job while attending college. A post-graduate student with two children in tow, her university funding not being enough to support her family. Two police collecting food for a ex-prisoner unable to leave their house. An older unemployed man suffering a benefit sanction, accompanied by his friend, who talked grimly about living through their third recession.

All appreciated the human kindness and solidarity demonstrated by the foodbank volunteers, and were surprised at the non-judgemental welcome and warmth they received. Compared to the coldness of the bureaucracy of the benefit system or other institutions, the difference with the foodbank was palpable.

What are foodbanks for?

Setting up a foodbank is an enormous undertaking, politically, socially, logistically. With limited resources it’s a legitimate question as to whether this is worth it. An argument is that its better to spend time fighting the source of the crisis – be it welfare reform, benefit sanctions, poor pay or extortionate rent – than spending our limited resources dealing with the symptoms like food poverty, which would resolve extremely quickly if the main problems were addressed.

This is a valid perspective, but it misses that foodbanks and other social organisations are a necessary instrument in the struggle against austerity, not a diversion from it. Human beings have needs, of which food is one of the most basic, which can no longer be met by this system. While we need to be challenging the attacks on welfare, the driving down of wages, the parasitic private renters and removal of rights and benefits which is driving millions into poverty, we cannot leave this chasm of human need created by the social crisis unfilled.

Our people, the poor, vulnerable, unemployed, migrants, disabled, need help and support with the day to day challenges of living under capitalism. Their capacity to resist and continuing struggling to change this system for the better rests on whether they are fed, clothed, have shelter and meaningful human interaction.

Creating a foodbank is a way of ensuring that austerity doesn’t impoverish people so much they are left wretched and are unable to resist its effects. It can provide a safety net which can give them avenues other than the payday loan companies, and prevents their misery becoming fodder for organised religious charities which will meet their needs but do nothing meaningful to change the situation, and actively discourage the forms of activity and politics which could.

Luton Foodbank works well to create avenues for people out of the worst effects of the crisis. It is not a political organisation and its board has a mix of local activists, trade unionists, Labour and Tory party members and councillors which prevents it taking a more political stance on the issue of food poverty.

However, there is no reason though why socialist activists could not organise foodbanks and other social services on a political basis, and use them not just to fill the gaps left by the state and capitalism, but through them create avenues to organise opposition to the system by those worst affected by it.

The Trussell Trust exists as a franchise which can be rolled out to churches and Christian organisations and provide them with a method of social action which fits with their Christian beliefs and utilises the institutions, organisations and networks which already exist. This report into the Trussell Trust’s activities gives a good overview of what it does, how it organises and its plans to expand in coming years.

The socialist movement should be learning from this, not simply disparaging it, and seeking to create its own accessible franchises to provide for human need; forms of social action which could be taken up by trade union branches, socialist groups, anti-cuts organisations and others interested in taking social as well as political action against the effects of austerity. A huge void exists in the socialist movement at present. While many socialist activists may profess their love of humanity, their desire to express solidarity with those suffering under capitalism, few socialists create organisations which do anything practical in this regard. There are thus few ways for socialists to demonstrate their socialist principles in practice. This also means the socialist movement is dominated by a focus on political action which rarely amounts in practice to more than a few meetings or rallies and a passive protest.

Those socialists who want to help out their fellow humans practically, rather than attend meetings and listen to speeches, find themselves excluded and sometimes denigrated, and probably end up taking part in activities organised by charities, many of which provide excellent and much-needed services for those affected by the crisis, but either remain neutral or actively resist any form of political action to resolve it.

Given the scale of the destruction wrought by austerity, it’s time the socialist movement resolved this contradiction positively, by abandoning its prejudices against social action, rediscovering its roots in forms of mutual aid and practical solidarity and began working with others to create social organisations which can help those worst affected by the crisis both socially and politically.

2 comments

2 responses to “How to start a foodbank: the story of Luton Foodbank”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

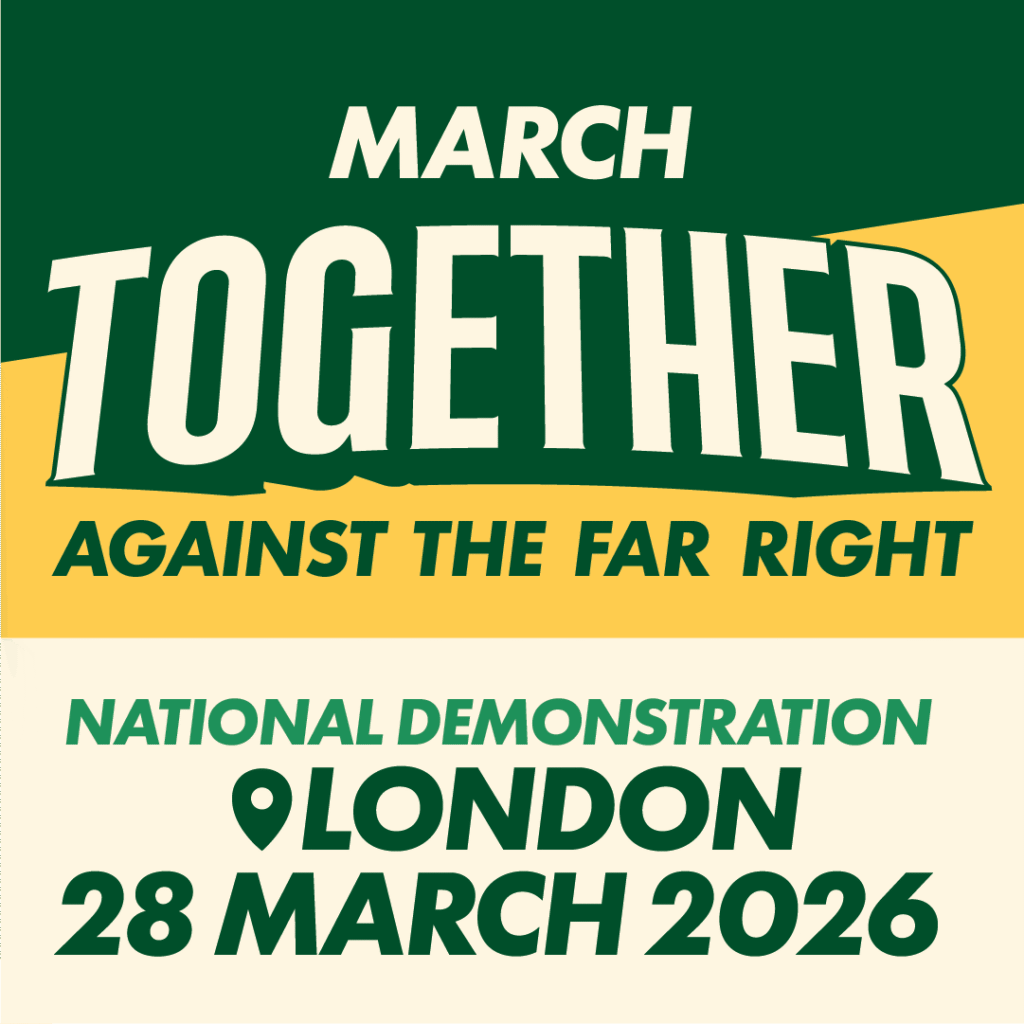

Saturday 28th March: March Together against the Far Right

Assemble central London 12 noon

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Great article need to see more like this engendering debate, etc: for me I think mutual aid is important and the need is massive, but is there a danger that F/B’s become normalised?, Duncan Smith released funds to the Tressell Trust well before the exponential rise in ‘clients’, he and the DWP knew what the reforms meant.

The Luton approach reminds me of the Black Panther stance called something like “Subsistence in advance of revolution” I.E People have to survive in the here and now before they are able to organise to overthrow capitalism

Really good project, good on you