Some remarks on the German elections

Murray Smith comments on the recent German elections and what they mean for Die Linke.

Murray Smith comments on the recent German elections and what they mean for Die Linke.

Once the immediate euphoria – for those that way inclined – had dissipated, it very quickly became apparent that the victory of Angela Merkel and the CDU in the German elections, obtained very largely at the expense of the CDU’s coalition partner, the FDP, was something of a poisoned chalice. Short of an overall majority, the CDU and its Bavarian ally the CSU, will have to get down to the business of coalition building with the SPD and/or the Greens. In the mainstream media it was being said before the election that in that case, no problem, forward to a grand coalition with the SPD. That was and is the general opinion among the leading circles in Europe. Not only is the SPD not seen as any kind of a threat, it is even seen by some as a more “pro-European” counterweight to Merkel. But it’s not as simple as that. The Financial Times woke up to reality on Wednesday with an article entitled “SPD splits open over alliance with centre-right”. A little overdone, perhaps, but the article dealt with a real problem: there is widespread opposition in the SPD to going into a coalition with the CDU. Partly for pragmatic electoral reasons: the SPD got its worst-ever result in 2009 after four years of such a coalition. But also, for many, out of political conviction. Many SPD members have never accepted the neo-liberal reforms of the Schroeder government and they have no desire to be part of a neoliberal coalition again.

The odds are still that the grand coalition will see the light of day, though not quickly; in 2005 it took 63 days of negotiations. Much pressure will be exerted on the SPD leadership. Merkel would probably have to make concessions on the minimum wage and some taxation of the rich. But the whole project could also fail, especially if there is an inner-party referendum in the SPD on the question, as many members are demanding. Either way it could be interesting. Either the SPD goes into coalition with a significant part of its own members against it, or else the members refuse, in which case the CDU would have to negotiate with the Greens. That would be difficult but not impossible. There appear to be some potential Nick Cleggs in the Green leadership.

All of this is actually good news for Die Linke. The party is now just, a whisker ahead of the Greens, the third party in the Bundestag. More to the point, it is clearly the main opposition party in terms of policies. So first of all, how well did Die Linke actually do? If you compare its results with those of 2009, it went down 3.3 per cent from 11.9 to 8.6. And it lost over a million votes. However that is not the comparison that is being made by most party members. They are looking back over the last couple of years, when the party was riven by internal differences and did not have a clear political profile. Die Linke was for a long time down at 6 or 7 per cent (and sometimes even in the danger zone at 5 per cent) in the opinion polls. That period, which it is not exaggerated to call a crisis, was overcome. It was clear at the party congress in Dresden in June that this was a party going into an election campaign united and rather confident. Not that there will not be any more debates and differences, in particular if the possibility of a coalition with the SPD and the Greens becomes concretized. At present it is mathematically possible, but politically excluded by the SPD and Green leaderships. In 2017 (or before) it might be different.

To come back over the last few months from 6-7 to 8-9, even 10 per cent in the polls and to end up with 8.6 is quite a remarkable achievement. The East-West difference is still there of course. Die Linke won over 20 per cent of the vote in the ex-GDR. But it also won over 5 per cent in the West, over 10 per cent in Bremen, 8.8 in Hamburg. Not much noticed outside of Germany was the Hesse state election the same day, where Die Linke managed to stay in the state parliament, which it entered in 2009. That is important. Die Linke, in the period following its launch in 2005, entered the parliaments of seven of the ten Western states and then failed to be re-elected in three of them at the next election. Last Sunday it got over the 5 per cent barrier in eight of them and just failed with 4.8 per cent in a ninth. Even in inhospitable Bavaria it got 3.8 per cent. As for the votes lost by Die Linke between 2009, I have not yet seen an analysis of where they went. Except that according to figures quoted by Peter Wahl of Attac Germany, 360,000 of them went to the Eurosceptic (and right-wing) Alternative for Germany. That underlines the necessity, in Germany and the eurozone, of having a clear socialist-European answer to the crisis of that zone and indeed of the EU. That will be the big challenge in next year’s European elections.

So where does Die Linke go from here? In the first place, it really is the opposition. In an interview with L’Humanité the day of the election Gregor Gysi, head of the party’s Bundestag group and arguably its most capable leader, listed six axes for the party in the new Bundestag, six points on which they will be the opposition: German military interventions abroad; arms sales (Germany is the number one arms exporter in the EU); the so-called solutions to save the euro; pension cuts and the increase in the retirement age; precarious employment; and the Hartz reforms of the Schroeder government. Gysi remarked that on these points Die Linke represented the majority of public opinion. Even more to the point, perhaps, they represent points on which many SPD members would agree with Die Linke, as would many trade unionists. Whether the SPD is in government or in opposition, those are points around which there can be unity in action. The question of a coalition with the SPD may be posed in the future, and Die Linke will react to that if and when it happens. But the real task is to overcome the historic divisions in the German workers’ movement, and to do so on an anti-capitalist basis. The creation of Die Linke in 2005, bringing together forces from the communist and social-democratic traditions, was a first step. Coming out of these elections, Die Linke looks well placed to continue on that road.

3 comments

3 responses to “Some remarks on the German elections”

Left Unity is active in movements and campaigns across the left, working to create an alternative to the main political parties.

About Left Unity

Read our manifesto

Left Unity is a member of the European Left Party.

Read the European Left Manifesto

ACTIVIST CALENDAR

Events and protests from around the movement, and local Left Unity meetings.

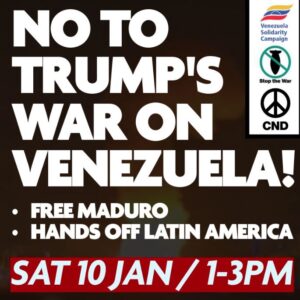

Saturday 10th January: No to Trump’s war on Venezuela

Protest outside Downing Street from 1 to 3pm.

More events »

GET UPDATES

Sign up to the Left Unity email newsletter.

CAMPAIGNING MATERIALS

Get the latest Left Unity resources.

Excellent article, Murray, thank you!

Another really helpful article on Die Linke.

More of this please on Bloco, Front de Gauche, Syriza, the Dutch Socialist Party. To be a part of a European Left we need to be better informed and be prepared to learn from our Continental comrades!

Mark P

german people asked which coalition they would most like to see and result was cdu/spd 48, cdu/grn 18 spd/left/grn 16. the more important figures would be what the individual spd voters want. an spd/left/grn coalish would need a mass movement argueing for negotitions between the three called something catchy like remove the cdu now? it would also need to be advocating policys that such a coalish could fufill that the cdu would not. if such a movement does not exist then a red green coalish will not and cannot happen. the imp thing is that the left avoid a second election in which merkel will be strenghthened. currently they have been weakened.